I’ve put in several articles by Nicole Foss here on these topics.

Resurgence of Risk – A Primer on the Develop(ed) Credit Crunch

The Inverted Pyramid – Money versus Credit (or Hyperinflation versus Hyperexpansion)

Money and credit are not the same thing, although people currently use them interchangeably. Money is a physical commodity, while credit is virtual wealth borrowed into existence. Money can be subject to inflation, either by printing currency or by debasing specie (reducing the precious metal content of coins), but does not disappear. Credit, on the other hand, can expand dramatically through financial alchemy, but has no physical existence, although its effects are certainly tangible.

Because credit is used as a money substitute in the financial markets, it acts as an inflationary force in the asset markets (and this spills over into the real world as the imaginary wealth thus created leads to overconsumption and malinvestments), but it is all ephemeral – in the end, it is still credit, not money. As soon as money is needed in lieu of credit, such as has now happened in the CMO and CDO markets, it becomes clear that the money simply isn’t there.”

Weimar Germany or present day Zimbabwe are examples of hyperinflation, but the Roaring Twenties and our situation are instead examples of credit hyperexpansion. Inflation is a chronic scourge, but credit expansions are self-limiting – they proceed until the debt that creates them can no longer be serviced, at which point that debt implodes in a sea of margin calls.

There is actually very little real cash out there relative to credit. The “sudden demand for cash” is in fact the world’s biggest margin call to date.

The value of credit is only as good as the promise that stands behind it, and when that promise cannot be kept, value abruptly disappears.

Let’s suppose that a lender starts with a million dollars and the borrower starts with zero. Upon extending the loan, the borrower possesses the million dollars, yet the lender feels that he still owns the million dollars that he lent out. If anyone asks the lender what he is worth, he says, “a million dollars,” and shows the note to prove it. Because of this conviction, there is, in the minds of the debtor and the creditor combined, two million dollars worth of value where before there was only one. When the lender calls in the debt and the borrower pays it, he gets back his million dollars. If the borrower can’t pay it, the value of the note goes to zero. Either way, the extra value disappears. If the original lender sold his note for cash, then someone else down the line loses. In an actively traded bond market, the result of a sudden default is like a game of “hot potato”: whoever holds it last loses. When the volume of credit is large, investors can perceive vast sums of money and value where in fact there are only repayment contracts, which are financial assets dependent upon consensus valuation and the ability of debtors to pay. IOUs can be issued indefinitely, but they have value only as long as their debtors can live up to them and only to the extent that people believe that they will.

Essentially, the gargantuan edifice of leveraged debt that has been accumulated during the years of credit expansion can be described as an inverted pyramid. Its point rests squarely on those at the bottom – for instance the subprime mortgage holders who’s relatively modest debts have been leveraged into trillions of dollars worth of derivatives. Each dollar of subprime mortgage debt probably underpins at least a hundred dollars of additional debt, and these loans will go into default en masse once the ARMs begin to reset in earnest. The leverage that has magnified gains on the way up, will magnify losses in a debt implosion on the way down.

Until now, his debt was an asset of the fund, and was being used as collateral against loans ten times its value. But the moment that Mr. Jones gave up on the idea of home ownership, the value of his mortgage simply disappeared. The paper asset, which derived its value from Mr. Jones’s promise, was destroyed. This had a cascading effect, since Mr. Jones’s mortgage was being used as collateral to borrow money to buy even more subprime mortgages, many of which were also defaulting. Assets purchased on borrowed money were now worthless. Only the debts remained, and suddenly there was more debt than the original amount that investors had put into the fund. These original funds would be needed repay the debts incurred by the fund. Nothing is left to return to investors.

Liquidity Traps and the Mood of the Market

Central bankers act as midwives for credit expansion – manipulating the cost of credit in order to encourage borrowing and lending. However, this cannot continue indefinitely as it does not occur in a vacuum. Central bankers have a range of options open to them, but ultimately the financial circumstances, and the mindsets, of both borrowers and lenders are important to whether or not credit expansion can be maintained.

Central bankers act as midwives for credit expansion – manipulating the cost of credit in order to encourage borrowing and lending. However, this cannot continue indefinitely as it does not occur in a vacuum. Central bankers have a range of options open to them, but ultimately the financial circumstances, and the mindsets, of both borrowers and lenders are important to whether or not credit expansion can be maintained.

The Fed really only can do two things. They can lower margin requirements for banks, the amount of capital they have to hold to make loans. That it has already driven to basically zero. So the Fed cannot allow banks any more “leeway” than it already has.

They can also perform open market money operations like REPOS and coupon passes. The Fed calls up big banks and buys their government bonds out of their portfolio. But they don’t buy them with real money; they buy them with credit newly created just for that purpose. The big bank can then lend that credit out in a much greater amount because the Fed only requires them to keep a small fraction of that credit to support whatever the bank wants to lend out. This is our wonderful fractional reserve system. If everyone went to the bank to get their “savings” at once they would find that they could get out less than 1%.

But here is the key. The bank must ultimately be willing to lend it and then find some investor to borrow it. This has been no problem whatsoever over the last several years. Now most investors realize that they have too much debt, that their level of income cannot support it. Banks realize this too and have increased their lending requirements. The last borrower is always the most aggressive speculator.

So most market participants are now looking for ways to pay back debt (deflation) just when the Fed is desperate to get investors to borrow more (inflation).

This conundrum is a form of liquidity trap – a shortfall in demand for credit that the policy tools of central bankers have great difficulty influencing. Keynes referred to this type of scenario as “pushing on a piece of string”. We are still in the early stages of this credit crunch and as yet, the Fed has not employed all the tools at its disposal. Most notably, it has not yet cut interest rates, likely due to recent Chinese threats to dump the dollar.

As the dollar should benefit from a flight to quality as credit spreads (the risk premium over treasuries) widen, there should be scope to cut interest rates later in the year. It is likely, however, that this will be less effective than the Fed would hope.

The theory is flawed. Central banks promising new credit to strapped banks only helps them with their current problems. It will not get new credit into a system that can’t take anymore. Banks, given their situation, are reducing drastically their new commitments, as they should. Borrowers can’t afford to borrow more.

The continuation of the credit expansion will remain dependent on a supply of ready, willing and able borrowers and lenders, and those already appear to be in short supply.

A trend of credit expansion has two components: the general willingness to lend and borrow and the general ability of borrowers to pay interest and principal. These components depend respectively upon (1) the trend of people’s confidence, i.e., whether both creditors and debtors think that debtors will be able to pay, and (2) the trend of production, which makes it either easier or harder in actuality for debtors to pay. So as long as confidence and productivity increase, the supply of credit tends to expand. The expansion of credit ends when the desire or ability to sustain the trend can no longer be maintained. As confidence and productivity decrease, the supply of credit contracts.

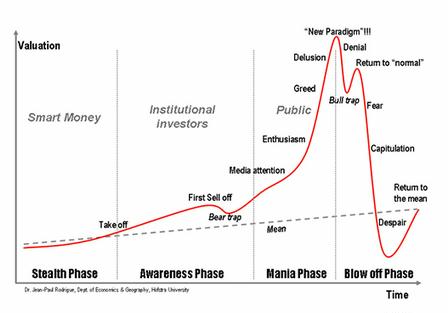

A significant headwind faced by the central bankers is the dramatic change in the mood of the market in recent weeks. It is said that humans have only two modes – complacency and panic, and markets, being a human construct, are no exception. The current mood of the market is one of fear, and if fear becomes panic, it can remove liquidity from the market far faster than even a central banker can pump it in. Actual cash is in short supply, and the many investors are afraid that the game of musical chairs will end before they can grab one of the very few chairs. If they do manage to find a chair, it will be difficult to convince them to part with it, no matter what the inducement. Risk has made a definitive comeback.

Deflation and the Mother of All Margin Calls

A credit expansion cannot be sustained indefinitely. At some point the burden of debt begins to stifle the ability to produce. The debt industry can take on a parasitic life of it’s own, becoming an integral part of the culture, from the level of the individual, as documented by James Scurlock in Maxed Out, to the level of corporations and government. The attention paid to assessing credit ratings, monitoring credit activity, hounding defaulters, writing off bad debt, juggling minimum payments, thinking of creative ways to exploit leverage, and encouraging every last entity to take on more debt in order that predatory lenders might wring out every last penny of profit, is attention not paid to productive activities of the kind that build successful economies. Eventually, it requires so much energy to maintain that economic performance suffers and extracting sufficient profit to cover interest payments on ever-increasing credit balances becomes impossible. A mood of conservation eventually takes hold, replacing the expansionary fervour, and reducing the velocity of money.

When the burden becomes too great for the economy to support and the trend reverses, reductions in lending, spending and production cause debtors to earn less money with which to pay off their debts, so defaults rise. Default and fear of default exacerbate the new trend in psychology, which in turn causes creditors to reduce lending further. A downward “spiral” begins, feeding on pessimism just as the previous boom fed on optimism. The resulting cascade of debt liquidation is a deflationary crash. Debts are retired by paying them off, “restructuring” or default. In the first case, no value is lost; in the second, some value; in the third, all value. In desperately trying to raise cash to pay off loans, borrowers bring all kinds of assets to market, including stocks, bonds, commodities and real estate, causing their prices to plummet. The process ends only after the supply of credit falls to a level at which it is collateralized acceptably to the surviving creditors.

In such an environment, financial values can disappear very quickly, leaving behind only stranded debt. All it takes for an asset class to be devalued is for as few as two parties among many to agree to a new lower price. The remainder need do nothing, other than refrain from disputing the new valuation, for their net worth to fall. In this way, a few discounted house sales can bring down the value of a neighborhood, and that lost value, which may have been underpinning a hundred times its worth in leveraged debt, is magnified through the inverted debt pyramid. The majority who do nothing end up watching the investment value of their assets plummet, while the owners of debt attempt to call in whatever value they can, from wherever they can, through margin calls.

The United States faces a severe credit crunch as mounting losses on risky forms of debt catch up with the banks and force them to curb lending and call in existing loans, according to a report by Lombard Street Research.

“Excess liquidity in the global system will be slashed,” it said. “Banks’ capital is about to be decimated, which will require calling in a swathe of loans. This is going to aggravate the US hard landing.”

“The complexity of this era of credit liquidation,” as Robert Smitley wrote of the Great Depression in ’30s America, “is far too great for the mob mind to grasp. It is hardly possible for them to see the picture wherein about $700 billion dollars of physical and intangible wealth is attempting to be turned into about $5 billion dollars of money.”

How much intangible debt now needs to be squeezed back into how much real money? It would be easier to find a cheap mortgage – with no ugly ARM once the teaser is finished – than guess at those numbers today.

We are expecting deflation at TAE (TheAutomaticEarth).

Inflation and deflation do not describe rising or falling prices.

Inflation and deflation are monetary phenomena. Inflation = an increase in supply of money and credit relative to available goods and services (deflation a decrease).

Rising prices are often a lagging indicator of an increase in the effective money supply, as falling prices are of a decrease. There is an important distinction to be made between nominal prices and real prices, however. Nominal prices can be misleading as they are not adjusted for changes in the money supply and so do not reflect affordability. Real prices, which are so adjusted, are a far more important measure.

Nominal prices typically rise during inflationary times as there is more money available to support higher prices, but prices need not rise evenly, and some prices may fall, depending on other factors. In real terms the picture would be quite different, as increases would be smaller and decreases would larger. When nominal prices fall despite inflation, it means that the price in real terms is plummeting. For instance, global wage arbitrage allowed the price of imported goods to fall drastically in real terms. In deflationary times, nominal prices typically fall across the board, but prices need not fall in real terms, and, in cases of scarcity, may well rise.

The easy availability of cheap credit has conveyed a considerable amount of price support – price support that will be progressively withdrawn as credit tightens. Prices will fall, but the collapse of credit will cause purchasing power to fall faster than price, leading to the apparent paradox of nominally cheaper goods being less affordable in the future than nominally more expensive goods are today. Moreover, there are likely to be substantial changes in relative prices between essentials and non-essentials. As a much larger percentage of a much smaller money supply will be chasing essentials such as food and energy, there will be relative price support for those items. In other words, while everything is becoming less affordable due to the collapse of purchasing power, essentials such a food and energy will be the least affordable of all, whatever the nominal price. People commonly speak of unaffordable prices as a result of inflation, but do not realize that deflation can have the same effect, only much more abruptly.

Thanks to a credit boom that dates back to at least the early 1980s, and which accelerated rapidly after the millennium, the vast majority of the effective money supply is credit. A credit boom can mimic currency inflation in important ways, as credit acts as a money equivalent during the expansion phase. There are, however, important differences. Whereas currency inflation divides the real wealth pie into smaller and smaller pieces, devaluing each one in a form of forced loss sharing, credit expansion creates multiple and mutually exclusive claims to the same pieces of pie. This generates the appearance of a substantial increase in real wealth through leverage, but is an illusion. The apparent wealth is virtual, and once expansion morphs into contraction, the excess claims are rapidly extinguished in a chaotic real wealth grab. It is this prospect that we are currently facing today, as credit destruction is already well underway, and the destruction of credit is hugely deflationary. As money is the lubricant in the economic engine, a shortage will cause that engine to seize up, as happened in the 1930s. An important point to remember is that demand is not what people want, it is what they are ready, willing and able to pay for. The fall in aggregate demand that characterizes a depression reflects a lack of purchasing power, not a lack of want. With very little money and no access to credit, people can starve amid plenty.

Attempts by governments and central bankers to reinflate the money supply are doomed to fail as debt monetization cannot keep pace with credit destruction, and liquidity injected into the system is being hoarded by nervous banks rather than being used to initiate new lending, as was the stated intent of the various bailout schemes. Bailouts only ever benefit a few insiders. Available credit is already being squeezed across the board, although we are still far closer to the beginning of the contraction than the end of it. Further attempts at reinflation may eventually cause a crisis of confidence among international lenders, which could lead to a serious dislocation in the treasury bond market at some point. If a debt-junkie economy can no longer easily raise funds, then interest rates would rise substantially and spending at home would be drastically cut. This would be the financial equivalent of hitting the ’emergency stop’ button on the economy, as it would cause a far larger rash of defaults than anything we have seen so far. We are not there yet though. Currently the dollar is benefiting from an international flight to safety, and it will probably continue to do so for some time, despite temporary counter-trend pullbacks from time to time.

We have seen a pattern of ebb and flow of market liquidity since February 2007, when the credit crisis arguably began. A constellation of market trends has largely moved in synch with liquidity. As liquidity falls, equities fall, bond yields fall (and prices rise), commodities fall, precious metals fall, real estate falls and the dollar rises, as cash becomes king. When we see market rallies, in contrast, rallies in bond yields, commodities, and metals are also common, and the dollar experiences a pullback. We appear to be beginning a market rally at the moment, which should lead to precisely this set of trend reversals. Such a rally is only temporary relief however. It may last for a couple of months, but then the decline should resume with a vengeance.

We have a very long way to fall, and the deleveraging process is likely to play out over several years. During this time we can expect to be mired in a worse depression than the 1930s, as the excesses that led to our current situation are far worse by every measure than were those of the Roaring Twenties. Unfortunately, we are much less prepared to face such an occurrence than were our grandparents. Our expectations are far higher, our knowledge and skill base is much less appropriate, we are far less self-sufficient and we have a structural dependency on cheap energy. This will be a very painful time. Deflation and depression are mutually reinforcing, leading to a vicious circle of decline that is very difficult to escape. It will be over when the (small amount of) remaining debt is acceptably collateralized to the (few) remaining creditors. At that point trust will begin to rebuild.

Hyperinflation

Some time ago, Gonzalo Lira wrote a couple of interesting pieces on hyperinflation, and I promised to respond to them. This has taken me a while, as there is much material to go through, many arguments to pick apart, areas of agreement and disagreement, differences in definitions and matters of timing.

The first article, How Hyperinflation Will Happen, is a long, thoughtful and detailed piece that I found interesting. There are many aspects I fundamentally disagree with, however, some for reasons of substance and others for reasons of timing.

Essentially the central proposition is that the US dollar is in danger of imminent demise due to a widespread loss of confidence, and that treasuries will be dumped en masse within a year, leading to hyperinflation, by which Mr Lira means price spikes. I do not see a loss of confidence in the dollar going forward, at least not soon. We have seen a long slide in the value of the dollar coincident with the rally in stocks. This is a reflection of a resurgence of confidence in being invested rather than being liquid, but this confidence is fragile and subject to rapid reversal.

I regard the extremely bearish sentiment regarding the dollar specifically as typical of a bottom. Trends take time to become established as received wisdom, and by the time they come to be generally accepted, they are much closer to an end than a beginning. When everyone is bearish, and has acted upon that sentiment, who is left to carry the trend any further in that direction? Market insiders will be taking the other side of the bet, as they always do at turning points. This is how they make their money – by recognizing and feeding off the sentiment of the herd.

When the market rally tops, I expect people to begin chasing liquidity in earnest – too late for many, as liquidity will get much harder to come by. Only a small minority will be able to cash out at the top. I fully expect the dollar to surge in relation to other currencies when this happens, on a knee-jerk flight to safety into the reserve currency as the least-worst option. At that time, I would not expect the US to have difficulties selling treasuries, because I think they will be regarded as the safest option in a horribly unsafe world. This is not rational, as the US is far past the point of no return on repaying its debt, but rationality is not the point, as herding impulses are never rational.

I would also expect the purchasing power of the remaining dollars (i.e. physical cash, of which there is actually very little) to increase substantially in relation to available goods and services domestically, as dollars will be both scarce and essential once credit virtually ceases to exist. Central authorities cannot print cash to alter this situation, as this would trigger an enormous increase in the risk premium charged by the bond market. Hence, cash will remain scarce, and people will hoard what little there is, compounding the effect of deflation through a fall in the velocity of money. In this regard, my view is diametrically opposed to Mr Lira’s.

I see far more imminent problems ahead for the euro than for the US dollar. I expect the shift from optimism to pessimism, that will define the end of the stock market rally, to lead to a rapid resurgence of fear over sovereign debt default risk in Europe. This can only exacerbate the widening regional disparities, and I think it will widen them to breaking point, for the eurozone and perhaps later for the EU itself.

As I have said before, the austerity measures coming for the whole European periphery are going to be severe enough to amount to political suicide for domestic politicians to implement. I think peripheral countries will choose to leave the euro, however high the cost of doing so, as the cost of staying in the eurozone could be even higher. If this does in fact happen, I think we would see an Argentine scenario, where savings are converted into the local currency (which would probably fall even compared with a falling euro), while debts remain in euros. These unpayable debts would then be defaulted on somewhat later. The level of uncertainty would almost certainly lead to massive capital flight from Europe, to America’s temporary benefit.

Naturally the dollar, like all fiat currencies, will eventually die, but I would argue that the time for that is not now. A dollar rally could be measured in years, although not many by any means. My best guess is that we would see perhaps a year or two of dollar rally in a world going increasingly haywire. After that I expect an end to the system of floating currencies, with all manner of attempts at competitive devaluation, currency pegs established and rapidly blown away, and beggar-thy-neighbour policies all round. The risk of currency reissue will rise over time, and be highly locational. I think the risk of reissue in the US is not imminent, but in Europe it should be a much larger concern, especially in peripheral countries.

I agree with this passage from Mr Lira’s article:

But this Fed policy—call it “money-printing”, call it “liquidity injections”, call it “asset price stabilization”—has been overwhelmed by the credit contraction. Just as the Federal government has been unable to fill in the fall in aggregate demand by way of stimulus, the Fed has expanded its balance sheet from some $900 billion in the Fall of ’08, to about $2.3 trillion today—but that additional $1.4 trillion has been no match for the loss of credit. At best, the Fed has been able to alleviate the worst effects of the deflation—it certainly has not turned the deflationary environment into anything resembling inflation.

Yields are low, unemployment up, CPI numbers are down (and under some metrics, negative)—in short, everything screams “deflation”.

This has been occurring under the most favourable of circumstances – a major rally during which people are prepared to suspend disbelief and give central authorities the benefit of the doubt. In all this time, and with all its efforts, the Fed has only been able to slow deflation. Once we turn the corner, confidence (and therefore liquidity) will evaporate again, and the headwind against the Fed will get very much stronger.

If they could not stop deflation under favourable circumstances, their odds of doing so under unfavourable ones must be extremely low. Periods of intense pessimism are not kind to central authorities. Everything they do is too little and too late. Every time they try and fail they look more desperate, which only acts to confirm people’s pessimism in a self-reinforcing spiral. Deflation has a massive psychological component, which the Fed has no tools to fight.

The second major proposition Mr Lira makes is that commodity prices will spike as a consequence of a meltdown in the treasury market:

At the time of the panic, commodities will be perceived as the only sure store of value, if Treasuries are suddenly anathema to the market—just as Treasuries were perceived as the only sure store of value, once so many of the MBS’s and CMBS’s went sour in 2007 and 2008.

It won’t be commodity ETF’s, or derivatives—those will be dismissed (rightfully) as being even less safe than Treasuries. Unlike before the Fall of ’08, this go-around, people will pay attention to counterparty risk. So the run on commodities will be for actual, feel-it-’cause-it’s-there commodities.

As I do not think such a treasury meltdown is imminent, I do not think such knock-on consequences are imminent either. In contrast, I think we are already seeing evidence of a top in commodities, which typically peak on fear of scarcity. I regard the sentiment indicators as strong evidence of such fear, and am therefore looking for a reversal, roughly coincident with a stock market top and a dollar bottom.

We have already seen significant speculative gains in commodities, similar to 2008, and I think that speculation will go into reverse, probably quite sharply. I would then expect a demand collapse to carry prices further to the downside. As I see a speculative reversal followed by a demand collapse setting up a supply collapse, I can see Mr Lira’s scenario possibly playing out in the future, quite possibly coincident with a bond market dislocation as he suggests. It is difficult to predict the timing for such an event, but I see it as being much further in the future than he does.

Because of my objection to the timing, I disagree with Mr Lira’s next assertion:

People—regular Main Street people—will be crazy to buy up commodities (heating oil, food, gasoline, whatever) and buy them now while they are still more-or-less affordable, rather than later, when that $15 gallon of gas shoots to $30 per gallon.

If everyone decides at roughly the same time to exchange one good—currency—for another good—commodities—what happens to the relative price of one and the relative value of the other? Easy: One soars, the other collapses.

When people freak out and begin panic-buying basic commodities, their ordinary financial assets—equities, bonds, etc.—will collapse: Everyone will be rushing to get cash, so as to turn around and buy commodities….[..]

…..This sell-off of assets in pursuit of commodities will be self-reinforcing: There won’t be anything to stop it. As it spills over into the everyday economy, regular people will panic and start unloading hard assets—durable goods, cars and trucks, houses—in order to get commodities, principally heating oil, gas and foodstuffs. In other words, real-world assets will not appreciate or even hold their value, when the hyperinflation comes.

In my view, by the time we see a commodity price spike, the value of people’s financial assets will already have evaporated, they will already have unloaded hard assets, and the dash for cash will already be in the past. I think at that point we will be well into a state of economic seizure, where credit will have disappeared, unemployment will have spiked, incomes will be very precarious, scarce cash will be being hoarded and it will be exceptionally difficult to connect buyers and sellers. Consequently, I do not see most people being in a position to engage in panic buying.

Some many be able to do this, but I think the resource grab is more likely to be a phenomenon operating at the level of the state than at the level of the individual, as most individuals will already have lost almost all their purchasing power. In my opinion, states will certainly engage in a resource grab, and will take supplies off the market, either by sending the tanks or the bilateral contract negotiators into resource-rich regions. States know perfectly well that oil is liquid hegemonic power, and they will be trying to secure their supply in whatever way they can.

I agree with Mr Lira that almost everything will be very much less affordable than it is now, and that this will happen quickly. I do not agree that prices will rise in nominal terms, or that this is in any way a requirement of a drastic fall in affordability. I expect prices to fall in nominal terms, but for purchasing power to fall much more quickly as credit evaporates. Thus as prices fall in nominal terms, affordability decreases, and the essentials end up being the least affordable of all. They will receive relative price support as a much larger percentage of a much smaller money supply ends up chasing them, hence any fall in their prices should be much smaller than for other goods and services. Thus I agree with Mr Lira that the essentials will be drastically less affordable, but I do not think nominal prices need to rise for this to happen.

When we see the inevitable price spike in the future, once demand collapse has led to supply collapse, we could easily see price increases in nominal terms. Against a backdrop of monetary contraction, this would mean prices were going through the roof in real terms (ie adjusted for changes in the money supply). Being able to obtain essentials will be a huge problem, and I fully expect ordinary people to be priced out of the market for many things at that point.

Their survival may then depend on rationing and bare-minimum level handouts. I think the problem will begin before this though, as a collapse in purchasing power prevents people buying essentials for lack of money long before essentials actually become scarce.

The next point of contention between my view and Mr Lira’s is his discussion of Japan’s fortunes:

That’s right: The parallels with Japan are remarkably similar—except for one key difference. Japanese sovereign debt is infinitely more stable than America’s, because in Japan, the people are savers—they own the Japanese debt. In America, the people are broke, and the Nervous Nelly banks own the debt. That’s why Japanese sovereign debt is solid, whereas American Treasuries are soap-bubble-fragile.

In my view, we are looking at a Japanese scenario in some ways, but on more of an Argentine timeline. Japan has been mired in a long and drawn out deflation, because they had an enormous pile of money to burn through before having to address their banking problems and also because they had an export-oriented economy at a time when they could exploit the largest consumer boom in global history. We are not so fortunate. We find ourselves in a huge debt hole, and as the economic seizure will be global, we will not be able to export our way out of anything, even if we still had yesterday’s productive capacity, which is in any case long gone thanks to global wage arbitrage.

I do not regard Japanese sovereign debt as solid. In fact I think Japan is very close to the final day of reckoning where the problems of the past must finally be faced head on. I see a banking collapse in their near future, compounded by their extreme dependence on imported resources, which they will not be able to afford if their export markets die for lack of consumers with purchasing power.

The main point of contention I have with Mr Lira centres around the longer-term prospects for the USA:

Instead, after a spell of hyperinflation, America will end up pretty much like it is today—only with a bad hangover. Actually, a hyperinflationist spell might be a good thing: It would finally clean out all the bad debts in the economy, the crap that the Fed and the Federal government refused to clean out when they had the chance in 2007–’09. It would break down and reset asset prices to more realistic levels—no more $12 million one-bedroom co-ops on the UES.

And all in all, a hyperinflationist catastrophe might in the long run be better for the health of the U.S. economy and the morale of the American people, as opposed to a long drawn-out stagnation. Ask the Japanese if they would have preferred a couple-three really bad years, instead of Two Lost Decades, and the answer won’t be surprising.

I do not see this as a transitory problem leading back to business as usual, and I mean NEVER returning to what we would now regard as business as usual, let alone doing so in only a couple of years.

Deflation and depression are mutually reinforcing. This is a persistent dynamic that should last at least as long as the last depression, and likely longer as every parameter is worse going into depression this time. We have more debt, far more structural dependencies (on cheap energy and cheap credit primarily), looming resource limitations, far higher expectations, a much larger population, a far smaller skill base etc.

I think we are looking at an economic catastrophe of unprecedented proportions, not a bump in the road that can be quickly consigned to history, if only we face our problems head on. In my view we are going to have to live through deflationary deleveraging, a long and grinding depression, and then quite possibly hyperinflation once the international debt financing model is broken, and with it the power of the bond market to constrain currency printing.

This could easily take twenty years to play out, and even then the upheaval is very unlikely to be over. The last time a major bubble burst – the South Sea Bubble of the 1720s – the aftermath lasted for several decades and culminated in a series of revolutions. This bubble is much larger, and the aftermath is likely to be proportional to the excesses of the preceding bubble.

Moreover, I do not see a return to what we consider to be business as usual at any point, because our business as usual scenario is critically dependent on cheap energy, and the energy subsidy inherent in fossil fuels has been a once in a planet’s lifetime deal. We are going to be living on an energy income instead of an energy inheritance, and this will mean living a life none of us in the developed world will recognize.