Preface. In the 70s and first half of the 80s population and immigration were on the platforms of ALL environmental groups. Today in mainstream media and most environmental groups, only nasty, racist people who hate black and brown people are mentioned. Never an interview with an ecologist, or discussion of limits to growth. Certainly the IPCC has no models of how less population would affect climate change, though it obviously would, since the reason for deforestation, wetland and biodiversity loss and all the other existential crises occur is to feed ever more people driving ever more cars burning ever more fossils to growth food, refrigeration, cooking, heating, cooling, and manufacture ever more goods for ever more people.

The Sierra Club was instrumental in making the topic of population and immigration taboo and politically incorrect because David Gelbaum gave them over $100 million dollars in exchange for not taking a position on these issues anymore (Weiss KR (2004) The Man Behind the Land. Los Angeles Times). And $100 million more since then according to Wikipedia.

I did a google search on population growth and climate change and looked at hundreds of results. I found three, only one of them mainstream. You have to go back to 2009 to start seeing articles on their connection. The dozen or so mainstream articles that do mention these two topics deny there is a connection, how dare anyone suggest such a racist thing. Kind of like the argument pro-gun advocates use to deny the need for gun control by saying “Guns don’t kill people, people kill people”.

Meanwhile, without free contraception and abortion world-wide through family planning, taxing more than one child, and other measures that are not harsh and voluntary, we come ever closer to Mother Nature solving the problem for us with drought, heat waves, and more — which has been the death of many civilizations in the past. With peak production of both conventional and unconventional oil in 2018, declining oil in the future will be the coup de grace, since for now we can buy our way out of it and stay alive with help from fossil fuels, such as to get the last fish in the ocean with giant ships and spotter planes in the Antarctic, air-conditioning in heat waves, refrigeration, industrially grow food for 8 billion people with gigantic tractors and combines and so on.

Alice Friedemann www.energyskeptic.com Author of Life After Fossil Fuels: A Reality Check on Alternative Energy; When Trucks Stop Running: Energy and the Future of Transportation”, Barriers to Making Algal Biofuels, & “Crunch! Whole Grain Artisan Chips and Crackers”. Women in ecology Podcasts: WGBH, Financial Sense, Jore, Planet: Critical, Crazy Town, Collapse Chronicles, Derrick Jensen, Practical Prepping, Kunstler 253 &278, Peak Prosperity, Index of best energyskeptic posts

***

UGC (2024) Population Growth. Understanding Climate Change, University of California, Berkeley

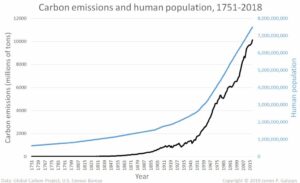

Population growth is the increase in the number of humans on Earth. For most of human history our population size was relatively stable. But with innovation and industrialization, energy, food, water, and medical care became more available and reliable. Consequently, global human population rapidly increased, and continues to do so, with dramatic impacts on global climate and ecosystems. We will need technological and social innovation to help us support the world’s population as we adapt to and mitigate climate and environmental changes.

Human population growth impacts the Earth system in a variety of ways, including:

- Increasing the extraction of resources from the environment. These resources include fossil fuels (oil, gas, and coal), minerals, trees, water, and wildlife, especially in the oceans. The process of removing resources, in turn, often releases pollutants and waste that reduce air and water quality, and harm the health of humans and other species.

- Increasing the burning of fossil fuels for energy to generate electricity, and to power transportation (for example, cars and planes) and industrial processes.

- Increase in freshwater use for drinking, agriculture, recreation, and industrial processes. Freshwater is extracted from lakes, rivers, the ground, and man-made reservoirs.

- Increasing ecological impacts on environments. Forests and other habitats are disturbed or destroyed to construct urban areas including the construction of homes, businesses, and roads to accommodate growing populations. Additionally, as populations increase, more land is used for agricultural activities to grow crops and support livestock. This, in turn, can decrease species populations, geographicranges, biodiversity, and alter interactions among organisms.

- Increasing fishing and hunting, which reduces species populations of the exploited species. Fishing and hunting can also indirectly increase numbers of species that are not fished or hunted if more resources become available for the species that remain in the ecosystem.

- Increasing the transport of invasive species, either intentionally or by accident, as people travel and import and export supplies. Urbanization also creates disturbed environments where invasive species often thrive and outcompete native species. For example, many invasive plant species thrive along strips of land next to roads and highways.

- The transmission of diseases. Humans living in densely populated areas can rapidly spread diseases within and among populations. Additionally, because transportation has become easier and more frequent, diseases can spread quickly to new regions.

***

Linden E (2022) The Climate Challenge of the World’s Population Hitting 8 Billion. Time magazine.

Global population surpassed 8 billion this week, a shocking milestone because back in the 1990s this threshold was not expected to be breached until 2050. Whether you’re a dour Malthusian or a technological optimist, one thing is undeniable: The 2.7 billion people added to global population since 1990 makes the task of averting a climate catastrophe vastly more challenging than it was when global warming first arose as a mainstream concern.

Getting to zero net emissions in 1990—when fossil fuels were putting 22.4 billion metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) into the atmosphere—was hard enough. Now, we have to eliminate those emissions along with roughly 14 billion tons of annual GHG emissions resulting from population growth.

One of actions to take is family planning, which until now has been largely absent from the conversation around global warming. Most of the expected 2 billion people will be born in the poorer nations. These nations burn fewer fossil fuels, but all aspire to raise their standard of living, which, given today’s energy mix, means more GHG emissions per capita. Even without economic growth, that population increase would mean roughly four billion additional metric tons of CO2 going into the atmosphere each year. That’s about a 10% increase, and, as of today, the world has never been able to voluntarily reduce annual emissions.

Population should be part of climate discussions, but I cannot remember a time when family planning has been featured in international efforts. Yes, it’s a hot button topic in many of the emerging nations, many of which take affront when the rich nations ask them to stabilize their numbers. But its absence from the agenda from last week’s COP27 is a tell that the Congress of Parties process is not a serious effort to really tackle the risk of climate change.

Population growth is the elephant in the room for climate change, but it is also the elephant in the room for ecological issues such as tropical deforestation, desertification, the extinction crisis, the destabilizing of earth’s life support systems on land and in the oceans; demographic issues such as involuntary migration, fresh water, and food insecurity; and political issues such as civil unrest and state failure. Slowing population growth will reduce pressures on all of these issues and threats.

Population growth is a fraught issue. In the last few decades, a major driver to limit family size has been the demographic shift towards urban areas. In cities, additional kids become a liability because of the higher costs of housing and food. This shows that people can change attitudes towards family size quite rapidly, given incentives and access to family planning. For governments, the incentive should be the prospect of a climate Hell if population continues to increase by several hundred million people every decade. Many emerging nations have made great strides in lowering infant mortality, but, all too often efforts on maternal and infant health are not coupled with access to family planning, which is one reason why human numbers surpassed 8 billion two decades ahead of schedule.

Laubichler M (2022) Population growth, climate change create an ‘Anthropocene engine’ that’s changing the planet. Salon.com

BMJ (2021) Human population growth is the root cause of climate change. British Medical Journal. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n2386

Behind a paywall for me, but I found this summary: “”Human population growth is the root cause of climate change” is a 2021 letter and comment in The BMJ by Jonathan Austen. The letter argues that population growth and increased consumption are the main causes of climate change. It suggests that population growth could be addressed through financial incentives for smaller families and free access to contraception. The letter also claims that population stability would lead to less deforestation and construction, which would have a significant impact on climate change”.

(2024) South Carolina’s population growth creates climate crisis, says environmental scientist

CHARLESTON, S.C. (WCIV) — South Carolina is growing, but not all growth is good. At least that is what Leon Kolankiewicz, an environmental scientist with NumbersUSA and lead author of “From Sea to Sprawling Sea,” an environmental impact study that explores how U.S. population growth has driven rural land loss across four decades, said.

“You are making it very difficult to achieve your climate goals by increasing the number of energy consumers, it just doesn’t work”. From 1982 to 2017, 35 years, South Carolina lost 2,126 square miles to what Kolankiewicz described as urban sprawl – the loss of rural land to urbanized development. “This pace of development, rural land loss, is accelerating,” Kolankiewicz said. “So that, quite understandably, has a lot of South Carolinians concerned or even upset.

Though politicians, including Gov. Henry McMaster, have praised South Carolina’s population growth, and paraded it around as proof of a “booming” economy, environmentalists like Kolankiewicz are concerned that urban sprawl, brought about by an increase in population, can steer areas like the Palmetto State – and the United States – into an existential crisis. “We face an issue of how human beings are going to live when there are 330 million of us in this country,” Kolankiewicz said. “We can’t keep doing that. It is unsustainable. You’re robbing Peter to pay Paul. Losing rural lands to urban sprawl can cripple the environment. Wildlife loses natural grazing land, farmers lose farmland and deforestation only adds to dramatic drops in air quality,” Kolankiewicz explained.

In his study, he contends that even if the loss of habitat and farmland continues at the lower rate of the 2002 to 2017 period, the average destruction of 1,200 square miles per year across the United States would be unsustainable for a country that desires the continued capability of food independence and stewardship of the animal and plant life currently living within its borders. “You can’t have growth in any object or entity in a finite system,” Kolankiewicz said. “Neither the United States, the biosphere, nor the world as a whole was growing in terms of resources to accommodate ever-increasing human demands.”

Kolankiwicz, who also wrote:

- Beck R, Kolankiewicz L (2000) The environmental movement’s retreat from advocating U.S. population stabilization (1970-1998): A first draft of history. Journal of policy history 12: 123-156.

- Kolankiewicz, L., et al. 2014. Vanishing Open Spaces Population Growth and Sprawl in America. Numbers USA.

***

Scientific American (2009) Does Population Growth Impact Climate Change? Does the rate at which people are reproducing need to be controlled to save the environment?

No doubt human population growth is a major contributor to global warming, given that humans use fossil fuels to power their increasingly mechanized lifestyles. More people means more demand for oil, gas, coal and other fuels mined or drilled from below the Earth’s surface that, when burned, spew enough carbon dioxide (CO2) into the atmosphere to trap warm air inside like a greenhouse.

According to the United Nations Population Fund, human population grew from 1.6 billion to 6.1 billion people during the course of the 20th century. (Think about it: It took all of time for population to reach 1.6 billion; then it shot to 6.1 billion over just 100 years.) During that time emissions of CO2, the leading greenhouse gas, grew 12-fold. And with worldwide population expected to surpass nine billion over the next 50 years, environmentalists and others are worried about the ability of the planet to withstand the added load of greenhouse gases entering the atmosphere and wreaking havoc on ecosystems down below.

Developed countries consume the lion’s share of fossil fuels. The United States, for example, contains just five percent of world population, yet contributes a quarter of total CO2 output. But while population growth is stagnant or dropping in most developed countries (except for the U.S., due to immigration), it is rising rapidly in quickly industrializing developing nations. According to the United Nations Population Fund, fast-growing developing countries (like China and India) will contribute more than half of global CO2 emissions by 2050, leading some to wonder if all of the efforts being made to curb U.S. emissions will be erased by other countries’ adoption of our long held over-consumptive ways.

“Population, global warming and consumption patterns are inextricably linked in their collective global environmental impact,” reports the Global Population and Environment Program at the non-profit Sierra Club. “As developing countries’ contribution to global emissions grows, population size and growth rates will become significant factors in magnifying the impacts of global warming.”

According to the Worldwatch Institute, a nonprofit environmental think tank, the overriding challenges facing our global civilization are to curtail climate change and slow population growth. “Success on these two fronts would make other challenges, such as reversing the deforestation of Earth, stabilizing water tables, and protecting plant and animal diversity, much more manageable,” reports the group. “If we cannot stabilize climate and we cannot stabilize population, there is not an ecosystem on Earth that we can save.”

CONTACTS: United Nations Population Fund, www.unfpa.org; Sierra Club’s Global Population and Environment Program, www.sierraclub.org/population; Worldwatch Institute, www.worldwatch.org.

One Response to Population growth creates climate crisis, says environmental scientist