Carl Safina, Sarah Chasis. 9 Oct 2004. Saving the Oceans. Two major commissions have proposed far-reaching reform of ocean policy. It’s time for Congress to act. Issues in Science & Technology. National Academy of Sciences.

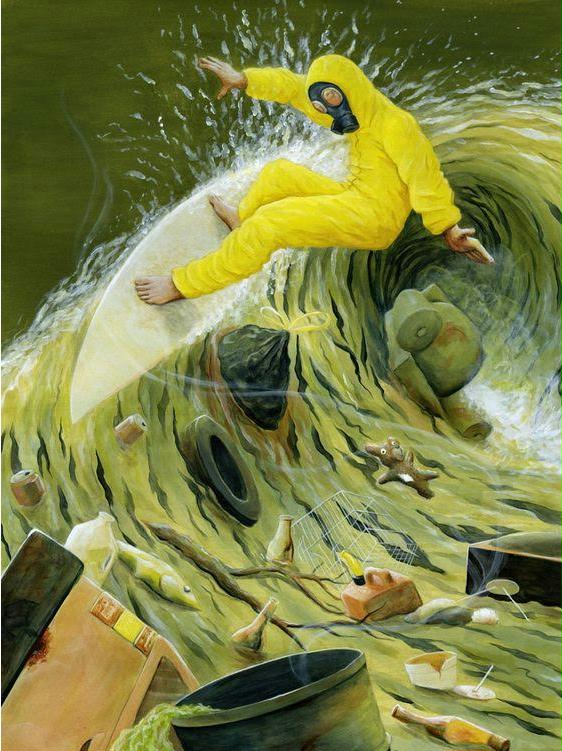

Oceans have been suffering from a variety of escalating insults for decades: excessive and destructive fishing; loss of wetlands and other valuable habitat; pollution from industries, farms, and households; invasion of troublesome species of fish and aquatic plants, and other problems. In addition, climate and atmospheric changes, which many scientists link to the combustion of fossil fuels and other human activities, are melting sea ice, changing ocean pH, stressing corals, killing plankton that are vital to the marine food web, increasing coastal erosion, and threatening to disrupt Earth’s temperatures in ways that will alter weather and deplete ocean life.

What do oceans do for us?

- Drive and moderate weather and climate

- Yield food and a variety of other products, such as pharmaceuticals; aid transportation

- Provide recreational opportunities

- Serve as a buffer that enhances national security.

- U.S. ports handle $700 billion worth of goods annually

- The cruise industry accounts for $11 billion in spending

- Commercial fishing’s total value exceeds $28 billion

- Recreational saltwater fishing has been estimated to be worth $20 billion.

- Offshore oil and gas industry produces $25 – $40 billion of product, and it contributes (through royalties and other fees) more than $4 billion to the U.S. Treasury.

- In a flourish refreshingly out of character for a government body, the commission notes, “We also love the oceans for their beauty and majesty and for their intrinsic power to relax, rejuvenate, and inspire. Unfortunately, we are starting to love our oceans to death.”

The many ways we’re assaulting the ocean

- Every 8 months, 11 million gallons of oil—equal to the Exxon Valdez oil spill—run off the nation’s streets and driveways or are poured into storm drains and enter the nation’s waters.

- Many other pollutants also find their way to sea.

- Well over half of coastal rivers and bays are moderately to severely degraded by excessive nutrients (many from fertilizers) that wash off the land from farms and households. These nutrients can increase the severity and frequency of harmful algal blooms that, in turn, can cause serious problems. The blooms can deplete oxygen levels in the water, thereby endangering fish and other forms of aquatic life and degrading coral reefs, and they can produce their own toxic chemicals that can directly poison sea life. As evidence of such problems, each summer, nutrient pollution from the Mississippi River creates in the Gulf of Mexico a “dead zone” the size of Massachusetts, where, on a sea floor devoid of oxygen, nothing can live.

- more than one-third of fish are overfished, several face possible extinction

- half of fish are caught using dragged nets and dredges that actually damage bottom habitat on which fish and other living resources depend. Indeed, fishing is changing relationships among species in food webs, altering the functioning of entire marine ecosystems.

- alien invasive species that have become established in coastal waters are increasingly displacing native species and altering food webs and habitats.

Tundy Agardy. 9 Jan 2004. America’s Coral Reefs: Awash with Problems. Issues in Science & Technology. National Academy of Sciences.

Reef Destruction

- From the disease-ridden dying reefs of the Florida Keys, to the over-fished and denuded reefs of Hawaii and the Virgin Islands, this country’s richest and most valued marine environment continues to decline in size, health, and productivity. The U.S. has jurisdiction over a surprisingly large proportion of extant coral reefs, including the world’s third largest barrier reef in Florida; a vast tract of reef systems throughout the Hawaiian Islands; and extensive reefs in U.S. territories such as Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam, American Samoa, and the Northern Mariana Islands. These reef resources contribute an estimated $375 billion to the U.S. economy annually, yet virtually all of these reef ecosystems are under threat, and many may be destroyed altogether in the coming decades.

- 5 percent of world commercial fisheries are reef-based, and over 50 percent of U.S. federally managed fishery species depend on reefs during some part of their life cycle

- Worldwide, some 30 percent of reefs have been destroyed in the past few decades, and another 30 to 50 percent are expected to be destroyed in 20 years’ time if current trends continue.

- In the Caribbean region, where many of the reefs under U.S. jurisdiction can be found, coral cover has been reduced by 80 percent during the past three decades.

- 37 percent of all corals in Florida have died since 1996

How are we killing the reefs?

- Eutrophication: overfertilization of waters from fertilizer, sewage, and animal wastes, which cause algae to overgrow and smother coral polyps; in extreme cases, leading to totally altered and biologically impoverished alternate ecosystems.

- Sediments that increase turbidity and reduce the sunlight reaching the coral colonies, one of the worst sources of sediment is from deforestation

- Overfishing. The removal of grazing fishes, for instance, increases the likelihood that algae will dominate the reef, causing a subsequent decline in productivity and diversity. Reef communities denuded of even relatively small numbers of fishes are also less likely to recover from episodic bleaching events, because recruitment is inhibited by the lack of grazing fishes to create settlement space. Similarly, declines in sea turtle species such as hawksbill and green turtles negatively affect reef ecology. The removal of top predators such as reef sharks, jacks, and barracudas can also cause cascading effects resulting in reduced overall diversity and declines in productivity. Despite these impacts, very few coral reef areas of the United States have fishing regulations expressly designed to prevent these ecological cascading effects from occurring. In fact, most people would be surprised to find out that even in seemingly protected reefs, such as those that occur within the Virgin Islands Biosphere Reserve around St. John, U.S.V.I., almost all forms of recreational and commercial fishing are allowed.

- Narrow tolerance ranges in temperature and salinity. Warming affects both coral polyp physiology and the pH of seawater, which in turn affects the calcification rates of hard corals and their ability to create reef structure. For this reason, even a slight warming of sea temperatures has dramatic effects, especially when coupled with other negative impacts such as eutrophication and overfishing. There is some indication that warming sea temperatures may render coral colonies vulnerable to the spread of disease or to increased mortality in response to normally nonpathogenic viruses and bacteria. The spread of known coral diseases and the emergence of new, even more debilitating diseases are alarming phenomena in the Florida Keys reefs and underlie many of the die-back episodes there in the past decade.

Recommended reading

Tundi Agardy et al., Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 13 (2003): 1-15.

Herman Cesar, Lauretta Burke, and Lida Pet-Soede, The Economics of Worldwide Coral Reef Degradation (WWF Netherlands, Zeist, Netherlands, 2003).

Michael J. Risk, Marine and Freshwater Research 50 (1999): 831-837.

C. Wilkinson, ed., Status of Coral Reefs of the World: 2000 (AIMS, Dampier, Australia, 2000).

Web page of the USCRTF (www.coralreef.gov).

Terry P. Hughes et al., “Climate change, human impacts, and the resilience of coral reefs” Science 301 (August 15, 2003): 929-933.