Excerpts from:

Ugo Bardi. August 28, 2011. The Seneca effect: why decline is faster than growth.

Ugo Bardi. July 15, 2013.The punctuated collapse of the Roman Empire.

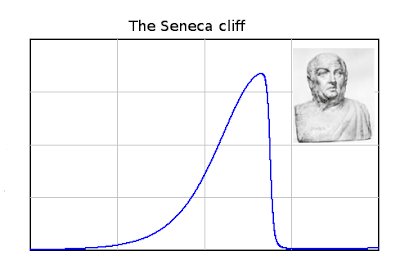

Could it be that the Seneca cliff is what we are facing, right now? If that is the case, then we are in trouble. With oil production peaking or set to peak soon, it is hard to think that we are going to see a gentle downward slope of the economy. Rather, we may see a decline so fast that we can only call it “collapse.” We need to understand what factors might lead us to fall much faster than we have been growing so far.

We can take the Hubbert model [which is a bell curve] as a first step for the description of an economic system based on the exploitation of a non renewable resource. The idea underlying the model is that exploitation starts with the best, highest return resources. Then, depletion slowly forces the industry to move to lower return resources. Profits fall and the capability of the industry to invest in new extraction falls as a consequence. This slows down growth and, eventually, causes production to decline (Bardi et al. 2010). So, it is a very general model that could describe not just regional cases but whole civilizations. Most of the agrarian civilizations of the past were based on a depletable resource, fertile soil.

There are models more sophisticated than the Hubbert model that can tell us more about worldwide trends. One is the “World3” model used for “The Limits to Growth” study, first published in 1972. The model is based on assumptions not unlike those at the basis of the Hubbert model , but it considers the world’s economy as a whole. Here are the results of the “base case” scenario of the 2004 version.

Bardi then explains of why the Hubbert oil depletion model doesn’t have a Seneca cliff but the Limits to growth model does. He says that perhaps what’s missing is pollution and the effects of pollution. Pollution has a cost: money and resources must be spent to fight it; be it water or air poisoning or effects such as global warming. The Fukushima disaster is a good example of pollution coming back to bite at the industry that produced it. It could be poisoning of the air or of water. It could be global warming and it could also be wars. Wars are great producers of pollution and a nuclear war would make the Seneca effect take place almost instantly.

Would technological progress save us from the Seneca cliff? Actually, it could make the cliff steeper!

You might try other ways to modify the model, for instance increasing its complexity by adding more stocks. How about a “bureaucracy” stock that accumulates and then dissipates energy? Well, it will act just as the “pollution” stock; perhaps we might say that bureaucracy is a form of pollution. [When you add complexities like pollution or bureaucracy] the model becomes more similar to Tainter’s model where civilizations decline and collapse because of an increase in complexity that brings more problems than benefits.There are many ways to modify these models and the Seneca effect is not the only possible outcome. But, in general, the Seneca effect is a “robust” feature of this kind of model and it comes up for a variety of assumptions. You ignore the Seneca cliff at your own risk.

I defined as the “Seneca Cliff” the tendency of some systems to collapse after having peaked. Here I start from some considerations about whether the collapse could be smooth or an uneven process that we could define as “punctuated.” I am taking the Roman Empire as an example and showing that it did decline much faster than it grew. But the decline was surely far from smooth.

The idea of an impending collapse of our civilization is already bad enough in itself, but it has this little extra-twist that collapse may be given more speed by what I called the “Seneca Cliff,” from the words of the Roman Philosopher who had noted first that, “Fortune is slow, but ruin is rapid“.

The idea of the fast (or Seneca-like) collapse does not necessarily mean that collapse will be continuous or smooth.

So, collapse may very well be “punctuated: a series of periods of temporary stability, separated by severe crashes. But it may still be much faster than the previous growth had been. Consider the Roman empire – it grew for about 900 years and collapsed over the next 400.

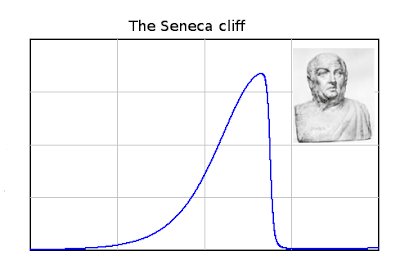

this image is from Wikipedia.

It shows the size of the Roman military over the Empire’s span of existence. WIth all the uncertainties involved, also this image shows a typical “Seneca” shape for both the Western and the Eastern parts of the Empire. Decline is faster than growth, indeed.