Tverberg, G. March 9, 2015. The oil glut and low prices reflect an affordability problem. ourfiniteworld.com

For a long time, there has been a belief that the decline in oil supply will come by way of high oil prices. Demand will exceed supply. It seems to me that this view is backward–the decline in supply will come through low oil prices.

The oil glut we are experiencing now reflects a worldwide affordability crisis. Because of a lack of affordability, demand is depressed. This lack of demand keeps prices low–below the cost of production for many producers. If the affordability issue cannot be fixed, it threatens to bring down the system by discouraging investment in oil production.

This lack of affordability is affecting far more than oil products. A recent article in The Economist talks about LNG prices being depressed. LNG capacity ramped up quickly in response to high prices a few years ago. Now there is a glut of LNG capacity, and prices are far below the cost of extraction and shipping for many LNG suppliers. At least temporary contraction seems likely in this sector.

If we look at World Bank Commodity Price data, we find that between 2011 and 2014, the inflation-adjusted price of Australian coal decreased by 41%. In the same period, the inflation-adjusted price of rubber is down 58%, and of iron ore is down 59%. With those types of price drops, we can expect huge cutbacks on production of many types of goods.

How Does this Lack of Affordability Come About?

The issue we are up against is diminishing returns. Diminishing returns mean that as we reach limits, it takes increased resources (usually both physical resources and human labor) to produce some type of product. Oil is product subject to diminishing returns. Metals of many kinds also are becoming increasingly expensive to extract. In many parts of the world, a shortage of water makes it necessary to use unusual techniques (desalination or long distance pipelines) to obtain adequate supply. The higher cost of pollution control can have a similar effect to diminishing returns on products with pollution issues.

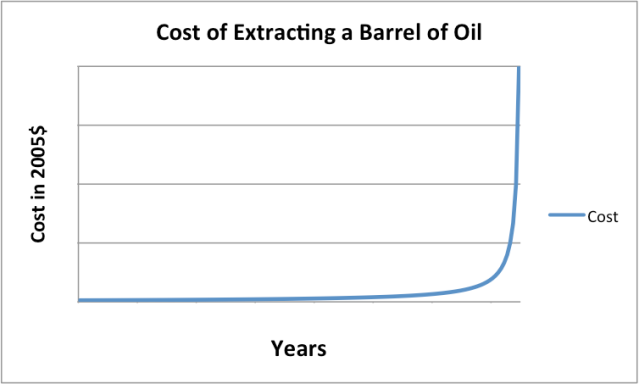

When we graph of the cost of production of resources subject to diminishing reserves, the result is similar to that shown in Figure 1.

What happens with diminishing returns is that cost increases tend to be quite small for a very long time, but then suddenly “turn a corner.” With oil, the shift to higher costs comes as we move from “conventional” oil to “unconventional” oil. With metals, the shift comes as high quality ores become depleted, and we need to move to mines that require moving a great deal more dirt to extract the same quantity of a given metal. With water, such a steep rise in diminishing returns comes when wells no longer provide a sufficient quantity of water, and we must go to extraordinary measures, such as desalination, to obtain water.

During the time when cost increases from diminishing returns were quite minor, it generally was possible to compensate for the small cost increases with technological improvements and efficiency gains elsewhere in the system. Thus, even though there was a small amount of diminishing returns going on, they could be hidden within the overall system.

Once the effect of diminishing returns becomes greater (as it has since about 2000), it becomes much harder to hide cost increases. The cost of finished products of many kinds (for example, food, gasoline, houses, and automobiles) starts rising, relative to the income of workers. Workers find that they must cut back on discretionary expenditures in order to have enough money to cover all of their expenses.

How Diminishing Returns Affect the Economy

There are at least three ways that diminishing returns adversely affects the economy:

- Lower wages

- Less ability to borrow

- Squeezing out other sectors of the economy

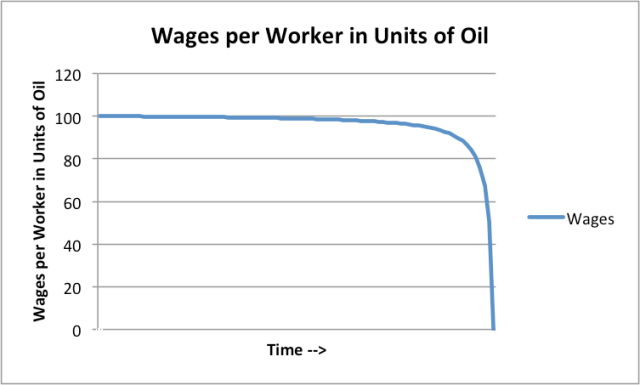

The reason for lower wages relates to the fact that, as the cost of producing a commodity rises, the worker is, in some sense, becoming less and less productive. For example, if we calculate wages per worker in units of oil, as oil becomes more expensive to extract, we get something like this:

A similar chart would hold for other resources that are becoming more difficult to extract, or whose cost of production is becoming higher because of greater pollution controls. For example, we would expect the wages of coal workers to be falling as well.

Also, as we shift to higher cost types of energy, we become increasingly inefficient in energy production. Based on a 2013 analysis, in the United States, there are more solar energy workers than coal miners, even though we use far more coal than solar energy. The large number of workers required to produce solar energy is one of the reason that solar energy tends to be high-priced to produce.

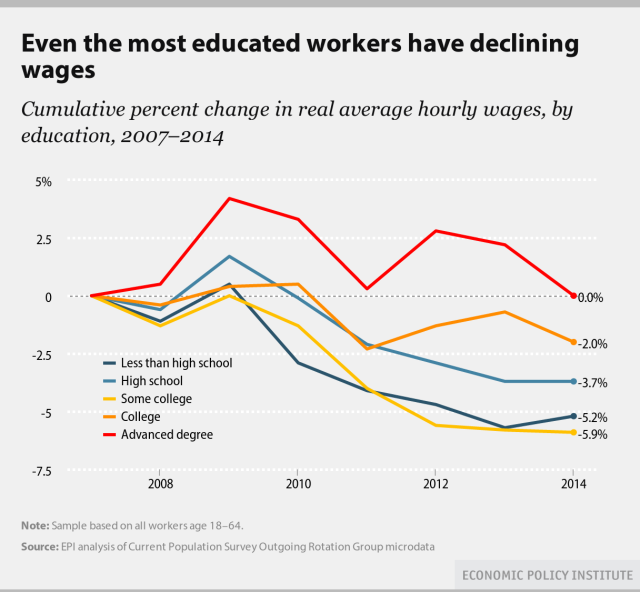

When we look at wages of workers, we indeed see a pattern of falling wages, especially for workers below the median wage. Figure 3 from the Economic Policy Institute shows that even the most educated workers are experiencing declining inflation-adjusted wages.

A second major issue affecting affordability is debt saturation. Affordability is favorably affected by rising debt–for example, it is a lot easier to buy a new car or house, if the would-be purchaser can obtain a new loan. If debt levels stay the same or fall, this becomes a problem–fewer goods can be purchased.

Governments in particular are reaching the limits of their borrowing capacity. They cannot keep adding new debt, and remain within historic debt to GDP ratios.

Another way debt saturation occurs relates to young people with student loans. They find it too expensive to borrow more money for a new car or for a home. Furthermore, the fact that wages are not keeping up with price increases for many workers reduces the borrowing ability of the workers with lagging wages. This is true, even if no student loans are involved.

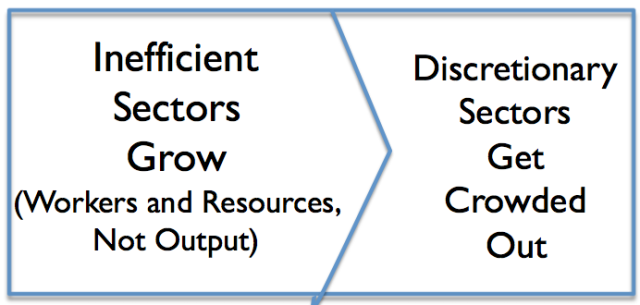

As mentioned above, a third issue is the fact that the inefficient sectors tend to squeeze out other portions of the economy by gobbling up a disproportionate share of workers and resources. The use of all of these resources doesn’t produce a lot of goods in the traditional sense–a desalination plant is expensive, but the amount of water produced per dollar of investment is not large. To the extent that the high costs of inefficient sectors are passed on to consumers, consumers find that they must cut back on discretionary spending. This cut-back in spending squeezes out discretionary spending, leading to cutbacks in discretionary sectors, and to reduced employment overall.

Wishful Thinking by Economists

Back before diminishing returns started becoming a major problem, economists created models regarding how the economy would react to higher cost of energy production and other symptoms of diminishing returns. In their view, if the cost of oil extraction rises, oil prices will rise to match these higher costs. Alternatively, substitution will take place, or technological changes will allow greater efficiency, or customers will cut back on their use of the high cost product. Somehow, these changes will take place without a particularly adverse impact on the economy.

Unfortunately, the models don’t correspond very well to what happens in practice–at least not for very long. It takes inexpensive energy to produce goods that workers can afford. Higher priced energy does not work well in this regard. Feedbacks that are not reflected in economic models reduce both wages and debt, making it harder to buy goods requiring the use of more-expensive energy products.

Furthermore, if the price of one commodity, for example oil, rises, then countries with very much oil in their energy mix find themselves handicapped in trade with other countries that use less oil in their energy mix. For example, a country that depends on tourism (which depends on oil use) for very much of its revenue, such as Greece, finds it difficult to find customers when oil prices are high. Lack of revenue can lead to financial problems for the country.

Because of the networked way the economy really works, prices for commodities can’t rise for the long-term. They may rise for a while, as consumers and governments borrow more, in an attempt to continue business as usual. Ultimately, though, the situation can’t “work.” Customers can’t afford to buy more homes and cars, unless their own wages are rising in inflation adjusted terms, and governments can’t collect enough tax revenue.

The issue we are dealing with here is lack of affordability. This is what will bring the system down–not the high priced scenario imagined by many. Decline will come through low prices, and a glut in oil supply, even if we are not looking for it from that direction.

Can commodity prices rise again?

It is not all that clear that they can rise again. It would be a lot easier for commodity prices to rise, if the problem were simply inadequate prices of one commodity, leading to a lack of that commodity. If the problem is inadequate demand for crude oil, coal, LNG, and iron ore the problem is much greater–especially if wages are still lagging.