In 2013, world total primary energy consumption was about 543 quadrillion British thermal units (Btu), and U.S. primary consumption was about 97 quadrillion Btu, equal to 18% of world total primary energy consumption. Source: Energy Information Administration. May 16, 2016. What is the United States’ share of world energy consumption?

[Former President Carter and General Wald both say the American public need to be better informed about the energy crisis to motivate them to stop buying gas-guzzling vehicles, since that’s why we go to war in the Middle East, at the cost of thousands of soldiers lives. Carter explains how hard it was to get bills past special interests, and our lack of an energy policy, except for the Carter doctrine, which Senator Lugar describes as the “United States will use its military to protect our access to Middle Eastern oil”. General Wald concludes “I don’t think we should overly frighten people, but they need to be aware of the fact that we are severely threatened today and vulnerable.”

Carter also explains how it was in the interest of both oil and car companies to keep vehicles inefficient:

“We have gone back to the gas guzzlers which I think has been one of the main reasons that Ford and Chrysler and General Motors are in so much trouble now. Instead of being constrained to make efficient automobiles, they made the ones upon which they made more profit. Of course, you have to remember, too, that the oil companies and the automobile companies have always been in partnership, because the oil companies want to sell as much oil as possible, even the imported oil-the profit goes to Chevron and others. I’m not knocking profit, but that’s a fact. And the automobile companies knew they made more profit on gas guzzlers. So, there was kind of a subterranean agreement there”.

Alice Friedemann www.energyskeptic.com author of “When Trucks Stop Running: Energy and the Future of Transportation, 2015, Springer]

Excerpts from: Senate 111–78. May 12, 2009. Energy Security: Historical perspectives and Modern challenges. U.S. Senate committee on foreign relations. 45 pages.

John Kerry, Senator from Massachusetts

“Why have we not been able to get together as a nation and resolve our serious energy problem?’’ These were the words of President Jimmy Carter in 1979. And regrettably, despite the strong efforts of President Carter and others, here we are, in 2009, still struggling to meet the same challenge today.

The downside of our continued dependence on oil is compelling, it is well known; and the downside is only growing.

Economically, it results in a massive continuous transfer of American wealth to oil-exporting nations, and it leaves us vulnerable to price and supply shocks.

But, the true cost of our addiction extends far beyond what we pay at the pump; its revenues and power sustain despots and dictators, and it obliges our military to defend our energy supply in volatile regions of the world at very great expense.

These were some of the problems that then-President Carter saw, understood, and defined, back in the latter part of the 1970s. They remain problems today. And to this long list of problems, we now add two very urgent, and relatively new, threats: Global terror, funded indirectly by our expenditures on oil, and global climate change driven by the burning of fossil fuels.

To make matters worse, we are adding billions of new drivers on the roads and consumers across the developing world, as India and China’s population and other populations move to automobiles, as lots of other folks did, all of that will ensure that the supplies of existing energy sources will grow even tighter.

All the trends are pointing in that wrong direction. According to the International Energy Agency, global energy demand is expected to increase approximately 45% between 2006 and 2030, fueled largely by growth in the developing world. So, we’re here today to discuss both the geostrategic challenges posed by our current energy supply and the need to find new and more secure sources of energy in the future.

From development to diplomacy to security, no part of our foreign policy is untouched by this issue. Region by region, our energy security challenge is varied and enormous.

Too often, the presence of oil multiples threats, exacerbates conflicts, stifles democracy and development, and blocks accountability.

- In Europe the potential for monopolistic Russian control over energy supplies is a source of profound concern for our allies, with serious implications for the daily lives of their citizens.

- In Nigeria, massive oil revenues have fueled corruption and conflict.

- In Venezuela, President Chavez has used oil subsidies to great effect to buy influence with neighbors.

- Sudan uses its energy supply to buy impunity from the global community for abuses.

- Iran uses petro dollars to fund Hamas and Hezbollah, and to insulate its nuclear activities from international pressure

- We know that, at least in the past, oil money sent to Saudi Arabia has eventually found its way into the hands of jihadists.

- And oil remains a major bone of contention and a driver of violence in Kirkuk and elsewhere among Iraq’s religious and ethnic groups.

And alongside these security concerns, we must also recognize that access to energy is fundamental to economic development. Billions of people who lack access to fuel and electricity will not only be denied the benefits of economic development, their energy poverty leaves them vulnerable to greater political instability and more likely to take advantage of dirty or local fuel sources that then damage the local environment and threaten the global climate.

Taken together, these challenges dramatically underscore a simple truth: Scarce energy supplies represent a major force for instability in the 21st century. That is why, even though the price of a barrel of oil is, today, $90 below its record high from last summer, we cannot afford to repeat the failures of the past.

Ever since President Nixon set a goal of energy independence by 1980, price spikes and moments of crisis have inspired grand plans and Manhattan projects for energy independence, but the political will to take decisive action has dissipated as each crisis has passed. That is how steps forward have been reversed and efforts have stood still even as the problem has gotten worse.

In 1981, our car and light-truck fleet had a fuel efficiency rate of 20.5 miles per gallon. Today, that number is essentially the same. The only difference? Back then we imported about a third of our oil; today we import 70 percent.

In recent years, Congress and the administration have made some progress. In 2007, fleet-wide fuel efficiency standards were raised for the first time since the Carter administration. In February we passed an economic recovery package which was America’s largest single investment in clean energy that we have ever made. [But] the lion’s share of the hard work still lies in front of us.

It’s a particular pleasure to have President Carter here, because President Carter had the courage, as President of the United States, to tell the truth to Americans about energy and about these choices, and he actually set America on the right path in the 1970s.

He created what then was the first major effort for research and development into the energy future, with the creation of the Energy Laboratory, out in Colorado, and tenured professors left their positions to go out there and go to work for America’s future.

Regrettably, the ensuing years saw those efforts unfunded, stripped away, and we saw America’s lead in alternative and renewable energy technologies, that we had developed in our universities and laboratories, transferred to Japan and Germany and other places, where they developed them. In the loss of that technology, we lost hundreds of thousands of jobs and part of America’s energy future. President Carter saw that, knew and understood that future. He dealt with these choices every day in the Oval Office, and he exerted genuine leadership. He’s been a student of these issues and a powerful advocate for change in the decades since, and we’re very grateful that he’s taken time today to share insights with us about this important challenge that the country faces.

JIMMY CARTER, Former PRESIDENT of the United States, Plains, Georgia

It is a pleasure to accept Senator Kerry’s request to relate my personal experiences in meeting the multiple challenges of a comprehensive energy policy and the interrelated strategic issues. They have changed very little during the past three decades.

Long before my inauguration, I was vividly aware of the interrelationship between energy and foreign policy. U.S. oil prices had quadrupled in 1973 while I was Governor, with our citizens subjected to severe oil shortages and long gas lines brought about by a boycott of Arab OPEC countries. Even more embarrassing to a proud and sovereign nation was the secondary boycott that I inherited in 1977 against American corporations doing business with Israel.

We overcame both challenges, but these were vivid demonstrations of the vulnerability that comes with excessive dependence on foreign oil. At the time, we were importing 50% of consumed oil, almost 9 million barrels per day, and were the only industrialized nation that did not have a comprehensive energy policy.

It was clear that we were subject to deliberately imposed economic distress and even political blackmail and, a few weeks after becoming President, I elevated this issue to my top domestic priority.

In an address to the Nation, I said: ‘‘Our decision about energy will test the character of the American people and the ability of the President and Congress to govern this Nation. This difficult effort will be the ‘moral equivalent of war,’ except that we will be uniting our efforts to build and not to destroy.’’

First, let me review our work with the U.S. Congress, which will demonstrate obvious parallels with the challenges that lie ahead. Our effort to conserve energy and to develop our own supplies of oil, natural gas, coal, and renewable sources were intertwined domestically with protecting the environment, equalizing supplies to different regions of the country, and balancing the growing struggle and animosity between consumers and producers.

Oil prices were controlled at artificially low levels, through an almost incomprehensible formula based on the place and time of discovery, etc., and the price of natural gas was tightly controlled—but only if it crossed a State line. Scarce supplies naturally went where prices were highest, depriving some regions of needed fuel. Energy policy was set by more than 50 Federal agencies, and I was determined to consolidate them into a new department. In April 1977, after just 90 days, we introduced a cohesive and comprehensive energy proposal, with 113 individual components. We were shocked to learn that it was to be considered by 17 committees and subcommittees in the House and would have to be divided into 5 separate bills in the Senate. Speaker Tip O’Neill was able to create a dominant ad hoc House committee under Chairman Lud Ashley, but the Senate remained divided under two strong willed, powerful, and competitive men, ‘‘Scoop’’ Jackson and Russell Long. In July, we pumped the first light crude oil into our strategic petroleum reserve in Louisiana, the initial stage in building up to my target of 115 days of imports. Less than a month later, I signed the new Energy Department into law, with James Schlesinger as Secretary, and the House approved my omnibus proposal.

In the Senate, the oil and automobile industries prevailed in Senator Long’s committee, which produced unacceptable bills dealing with price controls and the use of coal. There was strong bipartisan support throughout, but many liberals, preferred no legislation to higher prices. Three other Senate bills encompassed my basic proposals on conservation, coal conversion, and electricity rates.

I insisted on the maintenance of a comprehensive or omnibus bill, crucial—then and now—to prevent fragmentation and control by oil company lobbyists, and the year ended in an impasse. As is now the case, enormous sums of money were involved, and the life of every American was being touched. The House-Senate conference committee was exactly divided and stalemated. I could only go directly to the people, and I made three primetime TV speeches in addition to addressing a joint session of Congress.

Also, we brought a stream of interest groups into the White House—several times a week—for direct briefings. The conferees finally reached agreement, but under pressure many of them refused to sign their own report, and both Long and Jackson threatened filibusters on natural gas and an oil windfall profits tax. In the meantime, I was negotiating to normalize diplomatic relations with China, bringing Israel and Egypt together in a peace agreement, sparring with the Soviets on a Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty, allocating vast areas of land in Alaska, and trying to induce 67 Members of a reluctant Senate to ratify the Panama Canal treaties.

Our closest allies were critical of our profligate waste of energy, and OPEC members were exacerbating our problems. Finally clearing the conference committee and a last-minute filibuster in the Senate, the omnibus bill returned to the House for a vote just before the 1978 elections, and following an enormous White House campaign it passed, 207–206.

The legislation put heavy penalties on gas-guzzling automobiles; forced electric utility companies to encourage reduced consumption; mandated insulated buildings and efficient electric motors and heavy appliances; promoted gasohol production and car pooling; decontrolled natural gas prices at a rate of 10 percent per year; promoted solar, wind, geothermal, and water power; permitted the feeding of locally generated electricity into utility grids; and regulated strip mining and leasing of offshore drilling sites. We were also able to improve efficiency by deregulating our air, rail, and trucking transportation systems. What remained was decontrolling oil prices and the imposition of a windfall profits tax.

This was a complex and extremely important issue, with hundreds of billions of dollars involved. The big question was how much of the profits would be used for public benefit. By this time, the Iranian revolution and the impending Iran-Iraq war caused oil prices to skyrocket from $15 to $40 a barrel ($107 in today’s prices), as did the prospective deregulated price. We reached a compromise in the spring of 1980, with a variable tax rate of 30 percent to 70 percent, the proceeds to go into the general treasury and be allocated by the Congress in each year’s budget. The tax would expire after 13 years or when $227 billion had been collected. Our strong actions regarding conservation and alternate energy sources resulted in a reduction of net oil imports by 50 percent, from 8.6 to 4.3 million barrels per day by 1982—just 28 percent of consumption. Increased efficiency meant that during the next 20 years our Gross National Product increased four times as much as energy consumption. This shows what can be done, but unfortunately there has been a long period of energy complacency and our daily imports are now almost 13 million barrels.

The United States now uses 2.5 times more oil than China and 7.5 times more than India or, on a per capita consumption basis, 12 times China’s and 28 times India’s. Although our rich Nation can afford these daily purchases, there is little doubt that, in general terms, we are constrained not to alienate our major oil suppliers, and some of these countries are publicly antagonistic, known to harbor terrorist organizations, or obstruct America’s strategic interests.

When we are inclined to use restrictive incentives, as on Iran, we find other oil consumers reluctant to endanger their supplies. On the other hand, the blatant interruption of Russia’s natural gas supplies to Ukraine has sent a warning signal to its European customers. Excessive oil purchases are the solid foundation of our net trade deficit, which creates a disturbing dependence on foreign nations that finance our debt.

We still face criticism from some of our allies who are far ahead of us in energy efficiency.

A major new problem was first detected while I was President, when science adviser Frank Press informed me of evidence by scientists at Woods Hole that the earth was slowly warming and that human activity was at least partially responsible.

It is difficult for us to defend ourselves against accusations that our waste of energy contributes to [climate change]. Everywhere, we see the intense competition by China for present and future oil supplies (and other commodities), and their financial aid going to other key governments. Recently I found the Chinese to be very proud of their more efficient, less polluting coal power plants. They are building about one a month, while we delay our first full-scale model. We also lag far behind many other nations in … the efficiency of energy consumption

Let me emphasize that our inseparable energy and environmental decisions will determine how well we can maintain a vibrant society, protect our strategic interests, regain worldwide political and economic leadership, meet relatively new competitive challenges, and deal with less fortunate nations. Collectively, nothing could be more important.

An omnibus proposal could be addressed collectively by the Congress by committees brought together in a common approach to this complex problem, because no single element of it can be separated from the others. I think it would also minimize the adverse influence of special interest groups who don’t want to see the present circumstances changed or a new policy put into effect to deal with either energy or with the environment. Another advantage of an omnibus bill is it gives the President and other spokespersons for our Government, including all of you, an opportunity to address this so the American people can understand it.

I think that it is almost necessary to see a single proposal come forward combining energy and environment, as was the case in 1977 to 1980, so that it can be addressed comprehensively. This is not an easy thing, because now, with inflation, I guess several trillion dollars are involved; back in those days, hundreds of billions of dollars. And the interest groups are extremely powerful. I had the biggest problem, at the time, with consumer groups who didn’t want to see the price of oil and natural gas deregulated. It was only by passing the windfall profits tax that we could induce some of them to support the legislation, because they saw that the money would be used for helping poor families pay high prices on natural gas for heating their homes and for alternative energy sources.

Global warming is a new issue that didn’t exist when I was in office, although it was first detected then. I would hope that we would take the leadership role in accurately describing the problem, not exaggerating it, and tying it in with the conservation of energy. And the clean burning of coal, I think, is a very important issue, as well.

I mentioned very briefly the constraints that are already on us. We are very careful not to aggravate our main oil suppliers. We don’t admit it. But, we have to be cautious. And I’m not criticizing that decision. But, some of these people from whom we buy oil and enrich are harboring terrorists; we know it. Some of them are probably condemning America as a nation. They have become our most vocal public critics. We still buy their oil, and we don’t want to alienate them so badly that we can’t buy it.

We also see our allies refraining from putting, I’d say, appropriate influence—I won’t say ‘‘pressure’’—on Iran to change their policy concerning nuclear weapons because they don’t want to interrupt the flow from one of their most important suppliers of oil. So, I think, to the extent that the Western world and the oil-consuming world can reduce our demands, the less we will be constrained in our foreign policy to promote democracy and freedom and international progress.

One of the things that surprised me, back in the 1970s, was that we even lost a good bit of our supplies from Canada. Because when we had the OPEC oil embargo, Canada sent their supplies to other countries, as well. So, we can’t expect to depend just on oil supplies from Mexico and Canada. I would guess that our entire status as a leading nation in the world will depend on the role that we play in energy and environment in the future, not only removing our vulnerability to possible pressures and blackmail.

Senator Lugar (Indiana)

President Carter, in your State of the Union Address, January 23, 1980, you articulated what became known to many as the Carter Doctrine, that the United States would use its military to protec our access to Middle Eastern oil.

At the same time, in the same speech, you went on to say, ‘‘We must take whatever actions are necessary to reduce our dependence on foreign oil.’’ You have illustrated in your testimony today all the actions you took.

It seems to me to be a part of our predicament, historically, at least often in testimony before this committee, the thought is that our relationship with Saudi Arabia has, implicitly or explicitly for 60 years, said, ‘‘We want to be friends; furthermore, we want to make certain that you remain in charge of all of your oil fields, because we may need to take use of them. We would like to have those supplies, and in a fairly regular way.’’

Now, on the other hand, we have been saying, as you stated, and other Presidents, that we have an abnormal dependence on foreign oil. I suppose one could rationalize this relationship by saying that Saudi Arabia is reasonably friendly in comparison, to, say, Venezuela or Iran or Russia. And so, we might be able to pick and choose among them. Perhaps regardless of Presidential leadership, throughout all this period of time, the American public has decided that it wants to buy oil or it wants to buy products, whether it be cars, trucks, and so forth that use a lot of oil.

As our domestic supplies have declined, that has meant, almost necessarily, that the amount imported from other places has gone up. And so, despite the Carter Doctrine, say, back in 1980s, we have a huge import bill. Increasingly, our balance-of-payment structure has been influenced very adversely by these payments.

And so, many of us try to think through this predicament, and each administration has its own iteration. President Bush, most recently, in one of his State of the Union messages, said we are ‘‘addicted to oil.’’ At the same time, I remember a meeting at the White House in which he said, ‘‘A lot of my oil friends are very angry with me for making such a statement, said, ‘What’s happened to you, George?’ ’’

You know, there’s this ambivalence in the American public about the whole situation. Now, what I want to ask, from your experience, how could we have handled the foreign policy aspect and/or the rhetoric or the developments, say, from 1980 onward, in different ways, as instructive of how we ought to be trying to handle it now? I’m conscious of the fact that many of us are talking about dependence upon foreign oil. We can even say, as we have in this committee, that you can see a string of expenditures, averaging about $500 million a year, even when we were at peace, on our military to really keep the flow going, or to offer assurance.

Secretary Jim Baker once, when pushed on why we were worried about Iraq invading Kuwait, said of course it was the upset of aggression, but it’s oil. And many people believe that was the real answer, that essentially we were prepared to go to war to risk American lives, and were doing so, all over oil so we could continue to run whatever SUVs or whatever else we had here with all the pleasures to which we’ve become accustomed.

Why hasn’t this dependence, the foreign policy dilemmas or the economic situation ever gripped the American public so there was a clear constituency that said, ‘‘We’ve had enough, and our dependence upon foreign oil has really got to stop, and we are not inclined to use our military trying to protect people who are trying to hurt us’’? Can you give us any instruction, from your experience?

President CARTER

In the first place, no one can do this except the President—to bring this issue to the American public, to explain to them their own personal and national interest in controlling the excessive influx of oil and our dependence on uncertain sources. And it requires some sacrifice on the part of Americans— lower your thermostat. We actually had a pretty good compliance with the 55-miles-per-hour speed limit for a while, and people were very proud of the fact that they were saving energy by insulating their homes and doing things of that kind.

I made three major televised prime-time addresses, and also spoke to a special session of Congress, just on energy; nothing else. That was just the first year. I had to keep it up. The public joined in and gave us support. The oil companies still were trying to get as much as possible from the rapidly increasing prices. They were not able to do so because of the legislation passed.

In 1979, at Christmastime when the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, and I looked upon that as a direct threat to the security of my country. I pointed out to the Soviet Union, in a speech, that we would use every resource at our command, not excluding nuclear weapons, to protect America’s security, and if they moved out of Afghanistan to try to take over the oil fields in the Middle East, this would be a direct threat to our existence, economically, and we would not abide by it. And, secretly, we were helping the freedom fighters—some of whom are no longer our friends—in Afghanistan overcome the Soviet invasion. And it never went further down into Iran and Iraq. Unfortunately that same area was then taken over by the war between Iran and Iraq, and all the oil out of those two countries stopped coming forward in those few months. That’s when prices escalated greatly.

When I became President, the average gas mileage on a car was 12 miles per gallon, and we mandated, by the time I went out of office, 27.5 miles per gallon within 8 years. But, President Reagan and others didn’t think that was important, and so, it was frittered away. We have gone back to the gas guzzlers which I think has been one of the main reasons that Ford and Chrysler and General Motors are in so much trouble now. Instead of being constrained to make efficient automobiles, they made the ones upon which they made more profit. Of course, you have to remember, too, that the oil companies and the automobile companies have always been in partnership, because the oil companies want to sell as much oil as possible, even the imported oil—the profit goes to Chevron and others. I’m not knocking profit, but that’s a fact. And the automobile companies knew they made more profit on gas guzzlers. So, there was kind of a subterranean agreement there.

I would say that, in the future, we have to look forward to increasing pressures from all these factors. There’s no doubt that, as China and India, just for instance, approach anywhere near the per capita consumption of oil that America is using now, the pressure on the international oil market is going to be tremendous, and we’re going to, soon in the future, pass the $110-per-barrel figure again. And when that comes, we’re going to be in intense competition with other countries that are emerging. I’ve just mentioned two of the so-called BRIC countries. I’ve mentioned Brazil and China. But, we know that India is also in there, and Russia is, too. I used the example of the increasing influence of Brazil in a benevolent way. That’s going to continue. We’re going to be competitive with Brazil, and we’re also going to be competitive, increasingly, with China.

Everywhere we go in Africa, you see the Chinese presence, a very benevolent presence and perfectly legitimate. But, anywhere that has coal or oil or copper or iron or so forth, the Chinese are there, very quietly buying the companies themselves if they’re under stress, as they are in Australia right now, or they’re buying the ability to get those raw materials in a very inexpensive way in the future. We’re going to be competing with them. They have an enormous buildup now of capital because of our adverse trade balance and buying our bonds, and they’re able to give benevolent assistance now, wisely invested in some of the countries that I mentioned earlier. So, I think the whole strategic element of our dealing with the poorest countries in the world, of our dealing with friendly competitors, like Brazil, of our dealing with potential competitors in the future, like China, our dependence on unsavory suppliers of oil, all of those things depend on whether or not we have a comprehensive energy policy that saves energy and cuts down on the consumption and also whether we deal with environment.

Senator CARDIN of Maryland

You made an interesting observation that the interest groups will make it difficult for us to get the type of legislation passed that we need to get passed. I find it disappointing is our failure to get the interest groups that benefit from significant legislation active—as active as the opponents. So, is there any experience that you can share with us as to how we could do a better job in mobilizing these interest groups? I know there’s a patriotism, everybody wants to do the right thing, but, when it gets down to it, they’re also interested in what they think is in their best immediate interest. I agree that the legislation needs to be a bill that deals with energy and the environment, that if we separate it, we’re likely to get lost on both.

President CARTER

I deliberately mentioned three different interest groups—one was oil, one was automobiles, and one was consumers—just to show that there’s a disparity among them in their opposition to some elements of the comprehensive energy policy that I put forward. The oil companies didn’t want to have any of their profits go to the general treasury, renewable energy and that sort of thing. The consumers didn’t want to see the price of natural gas and oil deregulated, because they wanted the cheapest possible prices. The energy companies wanted to sell their natural gas, for instance, just in their own States where they were discovered, because the only price control on natural gas was if it crossed a State line. There was no restriction if they sold it in Texas or if they sold it in Oklahoma, where the gas was discovered. Those interest groups were varied, and they still are.

You will find some interest groups that will oppose any single aspect of the multiple issues that comprise an omnibus package, and they’ll single-shot it enough to kill it, and just the lowest common denominator is likely to pass if it’s treated in that way. The only way you can get it passed is to have it all together in one bill so that the consumers will say, ‘‘Well, I don’t like to see the increase in price, but the overall bill is better for me’’ and for the oil companies to say, ‘‘Well, we don’t like to see the government take some of our profits, but the overall bill is good for me.’’ That’s the only way you can hope to get it. It was what I had to deal with for 4 solid years under very difficult circumstances in the Congress and so forth. And I think that’s a very important issue to make.

And, to be repetitive, the only person that can do this is the President. The President has got to say, ‘‘This is important to our Nation, for our own self-respect, for our own pride in being a patriot, for saving our own domestic economy—for creating new jobs and new technology, very exciting new jobs, and also for removing ourselves from the constraint of foreigners, who now control a major portion of the decisions made in foreign policy and who endanger our security.’’ So, the totality is the answer to your question. You’ve got to do it all together in order to meet these individual special interest groups’ pressure that will try to preserve a tiny portion of it that’s better from them and, one by one, they’ll nibble the whole thing away.

I think that the fact that this Foreign Relations Committee is addressing this is extremely important, not just the Environmental Committee or the Energy Committee, but Foreign Relations, because it has so much to do with our interrelationship with almost every other country on Earth.

I would say this is about the only issue that I thought had to be treated comprehensively. It took me an entire 4 years. And I made so many speeches to the American people—fireside chats, and so forth—that the American people finally got sick of it, of my talking. [Laughter.] And the Congress was—the Senate and the House were very reluctant to take this up the second year, but I kept on the pressure, and I would say that it was costly, politically, just to harp on this issue repetitively. Anyway, I think, in general, comprehensive legislation may not be good, but, in this case, I think it’s absolutely necessary.

RICHARD G. LUGAR, U.S. SENATOR FROM INDIANA

For the better part of 50 or 60 years, our foreign policy had been deeply entwined with oil, in one form or another. Despite past campaigns for energy independence and the steady improvement in energy intensity per dollar of GDP, we are more dependent on oil imports today than we were during the oil shocks of the 1970s.

Now, we could have made a case for bringing democracy and human rights and education for children, and so forth, to a number of countries, but some would say, ‘‘This is, at best, sort of a second or third order of rationalization as to why you were there to begin with and what sort of wars you engendered by your physical presence.’’ And why were we there? Well, in large part because we were attempting, as President Carter expressed in the Carter Doctrine, to make certain we cannot be displaced from oil sources that were vital to our economy throughout that period of time.

We put people in harm’s way to make sure that all of those vital things occurred, did the best we could to rationalize that we were doing a lot of other good things while we were in the area. And that still is the case.

FREDERICK W. SMITH, CHAIRMAN, PRESIDENT & CEO, FEDEX Corp., CO-CHAIRMAN, Energy Security Leadership Council, Washington, D.C.

FedEx delivers more than 6 million packages and shipments per day to over 220 countries and territories. In a 24-hour period, our fleet of aircraft flies the equivalent of 500,000 miles, and our couriers travel 2.5 million miles. We accomplish this with more than 275,000 dedicated employees, 670 aircraft, and some 70,000 motorized vehicles worldwide. FedEx’s reliance on oil reflects the reliance of the wider transportation sector, and indeed the entire U.S. economy.

Oil is the lifeblood of a mobile, global economy. We are all dependent upon it, and that dependence brings with it inherent and serious risks. The danger is clear, and our sense of urgency must match it.

I understand that this may seem contradictory. We talk about ending our dependence on oil, and in the next sentence about drilling for more oil. But the reason for this is simple: Our safety and our security must be protected throughout the entire process. It would be ideal if we could simply snap our fingers and stop using petroleum today. But that is a pipe dream, not a policy. There are no silver bullets, and we cannot allow the perfect to be the enemy of the good—especially when faced with very real dangers to our economic and national security.

Energy and climate change are related issues. That said, it is important to emphasize that the fundamental goal of reducing oil intensity is a distinct one that needs to be considered based on its own merits and the very real dangers of inaction. Put simply, pricing carbon as a stand-alone policy, whether through a tax or a cap-and-trade system, will not allow us to reach that goal. Carbon pricing will almost automatically target the power industry in general and coal in particular. The power industry, however, is responsible for a fairly small percentage of the petroleum we consume as a nation. So pricing carbon will not meaningfully affect the price of oil, the demand for oil, and therefore oil dependence.

All you have to do is to watch the nightly news and look at the enormous human cost and the cost in national wealth of prosecuting these wars in the Middle East. And any way you slice it, in large measures they are related to our dependence on foreign petroleum. There are other issues, to be sure; but, just as Alan Greenspan said in his book, ‘‘neat,’’ you know, the situation was about oil. And if we continue along the road we’ve been on these last 40 years, we’re going to get into a major national security confrontation that makes these things that we’ve been in, here the last few years, pale in comparison. So, I think every American can understand that issue by just simply relating to what we’ve been involved in, the last few years, and watching the enormous human cost of these involvements that we have in areas of the world which we wouldn’t necessarily be involved in if we weren’t as dependent on foreign petroleum. We have other issues and other interests, but I think they would not require the level of boots on the ground that we’ve been forced to get into there in these last two wars.

GEN. CHARLES F. WALD, U.S. AIR FORCE (RET.), MEMBER, ENERGY SECURITY LEADERSHIP COUNCIL, WASHINGTON, DC

Energy security, to me, has been an important issue for the last at least two decades in my career; and, ironically, the first time it really became apparent to me, I think, in a big way, was when I was in War College in 1990, here in Washington, DC. And at that time, we were talking about strategy, which plenty of us thought we knew what it was, but we were learning. And the Carter Doctrine came up. And, at that time, I think, even then, 10 years after President Carter declared his doctrine, it was, I think, a surprise to many people that President Carter had been the first one to say that we would use military force to ensure the free flow of oil in the Middle East. That’s 38 years ago. Since then, I personally have spent years in the Persian Gulf, for example, and at least 16 years of my career overseas, much of it defending resources that are important to, not only us, but the rest of the global economy. And energy is, I think, paramount in that effort today and will continue to be. Our national security is definitely threatened by the fact that we are dependent upon oil and energy from places that don’t like who we are and what we do. Independence is not in the cards, necessarily, but becoming less dependent on places that don’t like us are certainly in the cards.

As you are all acutely aware, our country is now confronting a range of pressing challenges, both at home and abroad. The financial crisis, health care reform, and climate change are all serious issues that demand leadership and careful attention.

But based on my career and professional experience, I can think of no more pressing threat, no greater vulnerability, than America’s heavy dependence on a global petroleum market that is unpredictable, to say the least.

In 2006, I retired from the United States Air Force after 35 years of service. In my final assignment, I served as the Deputy Commander of United States European Command. Currently, EUCOM’s jurisdiction covers more than 50 countries and over 20 million square miles spanning the region north of the Middle East and subcontinent from the North Sea all the way to the Bering Strait. Though EUCOM is no longer responsible for Africa, it included that continent during my tenure.

During my tenure at EUCOM, I saw firsthand the dangers posed by our Nation’s dependence on oil. And those dangers have only become more acute in the time since.

The implicit strategic and tactical demands of protecting the global oil trade have been recognized by national security officials for decades, but it took the Carter Doctrine of 1980, proclaimed in response to the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan, to formalize this critical military commitment. In short, it committed the United States to defending the Persian Gulf against aggression by any ‘‘outside force.’’

President Reagan built on this foundation by creating a military command in the gulf and ordering the U.S. Navy to protect Kuwaiti oil tankers during the Iran-Iraq war.

The gulf war of 1991, which saw the United States lead a coalition of nations in ousting Iraq from Kuwait, was an expression of an implicit corollary of the Carter Doctrine: the United States would not allow Persian Gulf oil to be dominated by a radical regime—even an ‘‘inside force’’—that posed a dangerous threat to the international order.

The United States military has been extraordinarily successful in fulfilling its energy security missions, and it continues to carry out those duties with great professionalism and courage. But, ironically, this very success may have weakened the Nation’s strategic posture by allowing America’s political leaders and the American public to believe that energy security can be achieved by military means alone.

In the case of our oil dependence problem, however, military responses are by no means the only effective security measures, and in some case are no help at all.

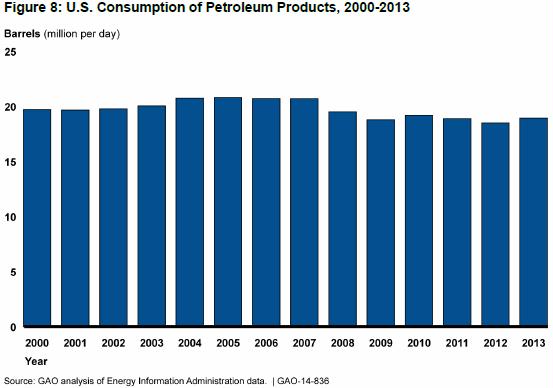

The United States now consumes nearly 20 million barrels of petroleum a day. About 11 million barrels—or 60% of the total—are imported. In 2008, we sent $386 billion overseas to pay for oil. Our oil and refined product, in fact, accounted for 57% of the entire U.S. trade deficit. This is an unprecedented and unsustainable transfer of wealth to other nations.

Our transportation system accounts for 70% of the petroleum we consume, and 97% of all fuel used for transport is derived from oil. In other words, we have built a transportation system that is nearly 100% reliant on a fuel that we are forced to import and whose highly volatile price is subject to geopolitical events far beyond our control.

In my time as a military leader, I labored to develop a proactive risk-mitigation strategy for just those kinds of geopolitical events. It was an unwieldy challenge. Petroleum facilities in the Niger Delta were subject to terrorist attacks, kidnappings and sabotage on a routine basis—just as they are today. Export routes in the Gulf of Guinea were plagued by piracy, just as routes in the Gulf of Aden have been more recently. We can share intelligence and train security forces, but our military reach is limited by cost, logistics, and national sovereignty.

In 2008, the 1-million-barrel-per-day BTC pipeline—which runs from the Caspian Sea in Azerbaijan to the Turkish port of Ceyhan—was knocked offline for 3 weeks after Turkish separatists detonated explosives near a pumping station, despite the best efforts of local security forces. The pipeline spewed fire and oil for days. The following week, Russian forces launched a month-long incursion into the Republic of Georgia during which the pipeline was reportedly targeted a number of times.

And sitting in the heart of the Middle East is the greatest strategic challenge facing the United States at the dawn of a new century: The regime in Tehran. We cannot talk about energy security, national security, or economic security without discussing Iran. From nuclear proliferation to support for Hezbollah, oil revenue has essentially created today’s Iranian problem. I recently participated in a study group sponsored by the Bipartisan Policy Center that produced a report titled, ‘‘Meeting the Challenge: U.S Policy Toward Iranian Nuclear Development. It is entirely possible that events related to Iran could produce an unprecedented oil price spike in the future, a spike that—given the fragility of the domestic and global economy—could very well be catastrophic.

With 90% of global oil and gas reserves held by state-run oil companies, the marketplace alone will not act preemptively to mitigate the enormous damage that would be inflicted by a serious and sudden increase in the price of oil. What is required is a more fundamental, long-term change in the way we use oil to drive our economy.

In the military, you learn that force protection isn’t just about protecting weak spots; it’s about reducing vulnerabilities before you get into harm’s way. That’s why reducing America’s oil dependence is so important. If we can lessen the oil intensity of our economy, making each dollar of GDP less dependent on petroleum, we would be less vulnerable if and when our enemies do manage to successfully attack elements of the global oil infrastructure. The best ways to reduce oil intensity are to bring to bear a diversity of fuels in the transportation sector.

The United States needs a comprehensive policy for achieving genuine energy security. This policy should include (1) increases in oil and natural gas production in places like the Outer Continental Shelf along with strict new environmental protections; (2) implementing fuel efficiency standards for all on-road transport that were signed into law last year;

One of the major issues in Afghanistan today is resupplying the troops with fuel. And it’s ironic that in Iraq we have ready access to readily available fuel out of Saudi Arabia. Today, there is no fuel whatsoever made in Afghanistan, there’s no pipelines that go in there. So, our troops have to be resupplied by convoy, which is problematic. You’ve seen what’s happened there. And then we fly in with airplanes that aren’t able to refuel; they can fly it back to Baku, so now we’re dependent on Azerbaijan, for example, or other places. So, that, in itself, is a huge strategic issue for us.

I think the biggest threat we face today, personally, in America is the Iranian situation, and I think that’s a difficult wild card. And if that situation goes in a direction that we don’t want it to be, we are going to be in a significant problem here in America, from an economic standpoint, as well as a security standpoint. So, I think there is a way for people to articulate this problem, and I think every time we seem to go someplace and talk about this, it resonates. So, I—frankly, I believe it starts right here in Washington. And I don’t think we should overly frighten people, but they need to be aware of the fact that we are severely threatened today and vulnerable.