McGrath, M. 2015-11-25. The Alaska fishing village taking on ‘Godzilla’. BBC News

Image copyright Pete Niesen

Image copyright Pete Niesen [See original article for details, what follows is reduced and most pictures removed]

Alaska is a vast wilderness of natural beauty. But it also holds more coal than all the other US states put together. As world leaders prepare to gather for a major climate change summit, plans to build an open coal mine that would cover 78 sq km (30 sq miles) surrounding a valued Alaskan river could be coming to a head.

Al Goozmer is about to take on Godzilla. One more time. We are standing on the sandy edge of the Chuitna River, and Al, the president of the Tyonek Native Village, is holding some small lumps of coal in his hand. This is the coal that the indigenous people in his small settlement have collected and used for generations as a fuel source, the coal that emerges on the beach from under the river, part of a huge mother lode that stretches about a dozen miles inland.

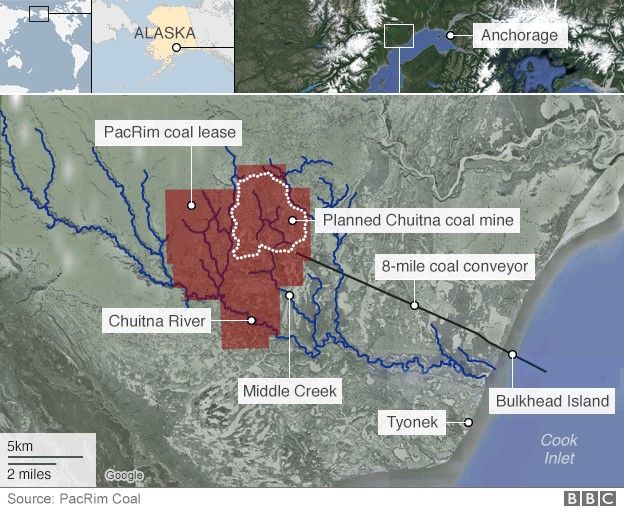

Godzilla is what Al calls the proposed development of an open cast, strip coal mine at that site, that would encompass over 5,000 acres. It would be the largest in Alaska. The ore would then travel along a permanent 18km transporting chute, over the river, out to waiting ships in the Cook Inlet.

Destination? Power stations in China.

Al and many in his community think the development will be a disaster for his village and their way of life. “I call it my cathedral, an open-air cathedral, I come here to meditate and pray,” Al says as we survey the beach littered with tree trunks and other river-borne natural debris.

Tyonek is a gated indigenous community of around 200 people by the edge of the sea, just 64km across the Cook Inlet from Anchorage. In Tyonek there are no open roadways – you have to fly in or come by boat when the sea is calm. You also have to be invited. Tribal regulations permit visitors if someone vouches for them, and they stay less than 24 hours.

The villagers are called the Tebughna – the Beach People. They speak an Athabascan dialect called Dena’ina and can trace their origins in the area back 1,000 years. Their first recorded encounter with Europeans came when tribe members met Captain James Cook in 1778.

Then as now, many natives of Tyonek subsist by hunting and fishing, with salmon from the rivers being a significant part of their diet.

Sitting in the tribal center building, surrounded by black-and-white pictures of the village down the years, Frank recalls how commercial fishing, oil and timber industries have all come to Tyonek to exploit natural resources.

It has always ended badly, he says. I personally have experience with timber and lumber. They came here in the 1970s and promised us jobs. We ended up being labourers, then they fired us.”

Al Goozmer believes it will be the same if the coal project goes ahead. “Those industries left our shores with their pockets full of money and left behind shattered lives and broken promises. Now we see coal as the Godzilla of development here on the west Cook Inlet.”

The Chuitna River is not the only place in Alaska that has considerable resources of coal. Alaska is said to have more reserves than the lower 48 states put together.

The US Geological Survey estimates there are more than 4 trillion metric tonnes of coal as a total resource in the state, though how much of this is recoverable is open to question.

Certainly the low sulfur, sub-bituminous coal that is in the Chuitna basin is attractive for export. It contains less carbon and mercury than other types of coal.

PacRim Coal didn’t respond to requests for an interview, but according to their website, the company expects to produce around 12 million tonnes of coal per year, making it more productive than the biggest mine in Russia.

Al Goozmer says they will discharge seven million gallons of waste water into the Chuitna River every day. He fears the toxic elements will disorient the salmon returning to spawn. When the salmon go, a vital source of protein and a key part of the village culture could be lost.

“We’ve been teaching our kids how to fish their whole lives,” says Gwen Chickalusion who is a cook at the school and looks after the bountiful community garden.

“If we don’t have the fish, the only option will be to go to Anchorage and go shopping – we can’t just jump in our trucks and go down the road. They say they could reclaim it and make it just like before, but how many years will it take? How many years will I go hungry for moose or fish, if they ever return again?”

Back on Tyonek, another small aircraft trundles to a halt on the shingle runway in the cold, spitting rain. As we watch, Al tells me he worries that if coal exports to China go ahead, they will rebound badly on Alaska.

“Alaska is the most sensitive area in the world for climate change and we see that every day. The river is named after my grandfather. One of my uncles was a historian and lay preacher here. He taught me all the old stories of who we are and what we are. I don’t believe that coal is a vital source of power for the world or anyone,” he says. “It’s good right where it is at. Leave it there.”