Goh Chun Teck, Lim Xian You, Sum Qing Wei, Tong Huu Khiem. 2011. Resource Wars. Players compete with each other for territories that generate resources such as coal, water, gold and gas. A Player can sell resources for money, which he can use to purchase even more territories to grow his empire, or fight with other players to attempt to conquer their territories. National University of Singapore.

[ About half of the pages are images from Brigadier General John Adams “Remaking American security. Supply chain vulnerabilities & national security risks across the U.S. Defense Industrial Base”.

Alice Friedemann www.energyskeptic.com author of “When Trucks Stop Running: Energy and the Future of Transportation, 2015, Springer]

House 113-63. July 25, 2013. The Emerging threat of Resource Wars. U.S. House of Representatives, 88 pages.

DANA ROHRABACHER, California. We import 750,000 tons of vital minerals and material every year. An increasing global demand for supplies of energy and strategic minerals is sparking intense economic competition that could lead to a counterproductive conflict.

A ‘‘zero sum world’’ where no one can obtain the means to progress without taking them from someone else is inherently a world of conflict.

Additional problems arise when supplies are located in areas where production could be disrupted by political upheaval, terrorism or war.

When new sources of supply are opened up, as in the case of Central Asia, there is still fear that there is not enough to go around and thus conflict emerges. The wealth that results from resource development and the expansion of industrial production increases power just as it uplifts economies and uplifts the standards of peoples.

This can feed international rivalry on issues that go well beyond economics. We too often think of economics as being merely about ‘‘business’’ but the distribution of industry, resources and technology across the globe is the foundation for the international balance of power and we need to pay more attention to the economic issues in our foreign policy and what will be the logical result of how we deal with those economic and those natural resource issues.

The control of access to resources can be used as political leverage, as we have seen with Russia and China. They both have demonstrated that. Indeed, China is engaged in an aggressive campaign to control global energy supply chains and to protect its monopoly in rare earth elements. This obviously indicates that Beijing is abandoning its ‘‘peaceful rise’’ policy. This is not an unexpected turn of events given the brutal nature of the Communist Chinese regime.

Who owns the resources, who has the right to develop them, where will they be sent and put to use, and who controls the transport routes from the fields to the final consumers are issues that must be addressed. Whether the outcomes result from competition or coercion; from market forces or state command, we will be determining how to achieve and if we will achieve a world of peace and an acceptable level of prosperity or we won’t achieve that noble goal.

My father joined the Marines to fight World War II and it is very clear that natural resources had a great deal to do with the Japanese strategies that led to the Second World War and so we have some of our witnesses may be talking to us and will be talking to us on issues that are of that significance.

WILLIAN KEATING, MASSACHUSETTS. Today’s hearing topic provides us with an opportunity to look beyond Europe and Eurasia and examine the global impact of depleting resources, climate change and expanding world population and accompanying social rest.

In March, for the first time, the Director of National Intelligence, James R. Clapper, listed ‘‘competition and scarcity involving natural resources’’ as a national security threat on a path and on a par with global terrorism, cyber war, and nuclear proliferation.

He also noted that ‘‘terrorists, militants, and international crime groups are certain to use declining local food security to gain legitimacy and undermine government authority’’ in the future. I would add that the prospect of scarcities of vital resources including energy, water, land, food, and rare earth elements in itself would guarantee geopolitical friction.

Now add lone wolves and extremists who exploit these scenarios into the mix and the domestic relevance of today’s conversation and you can see the importance of this is clear.

Further, it is no secret that threats are more interconnected today than they were 15 years ago. Events which at first seem local and irrelevant have the potential to set off transnational disruptions and affect U.S. national interests. We saw this dynamic play out off the coast of Somalia where fishermen were growing frustrated from lack of government enforcement against vessels harming their stock and where they took up arms and transitioned into dangerous gangs of pirates. Now violent criminals threaten Americans in multinational vessels traveling through the Horn of Africa. Unfortunately, I don’t see a near term end to the coordinated international response that this situation requires. I agree with Mr. Clapper that the depletion of resources stemming from many factors which above all include climate change has potential to raise a host of issues for U.S. businesses worldwide.

PAUL COOK, CALIFORNIA. In my former life besides being in the military for 26 years, I was a college professor and I have to admit I taught history and I always have got to give the old saw that people who do not understand history are bound to repeat it.

If you look at the history of conflicts and wars and everything else and whether you go back to that famous book, The Haves and Have-Nots, it is always about resources and who has it and who doesn’t have them and who wants them.

But I think we as a country, at least have not picked up on those lessons of history and we are very, very naive about the motivations of certain countries and why they do certain things. And obviously, there are things going on throughout the world right now in Eurasia which underscores some of the things that we are going to talk about today. So I applaud having a hearing on this. I think the title says it all, resource wars, and if we don’t have the war yet, we have had it in the past and we are going to have it in the future.

BRIGADIER GENERAL JOHN ADAMS, USA, RETIRED, PRESIDENT, GUARDIAN SIX CONSULTING, LLC

“Remaking American Security” examines 14 defense industrial base nodes vital to U.S. national security. We investigated lower tier commodities and raw materials and subcomponents needed to build and operate the final systems. Based on our research, the current level of risk to our defense supply chains and to our advanced technological capacity is very concerning.

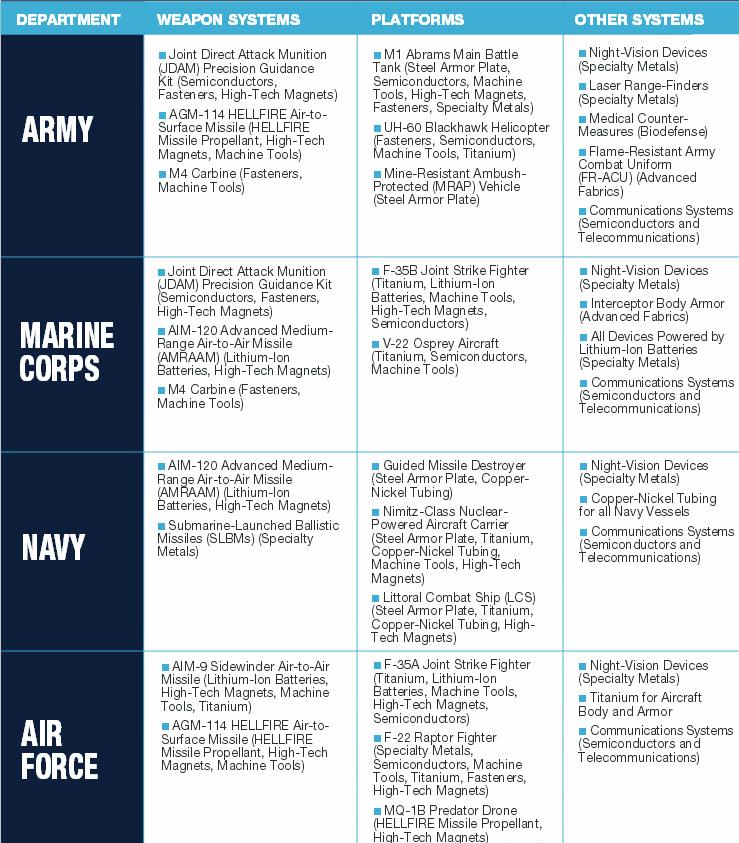

Figure 1. Brigadier General John Adams. May 2013. Military Equipment Chart: Selected defense uses of specialty metals. Remaking American security. Supply chain vulnerabilities & national security risks across the U.S. Defense Industrial Base. Alliance for American Manufacturing.

The bottom line is that foreign control over defense supply chains restricts U.S. access to critical resources and places American defense capabilities at risk in times of crisis. In the report, we devote a chapter to the importance of access to specialty metals and rare earth elements. Increasingly, these resources are central to modern life and central to modern defense preparedness. The United States has become dependent on imports of key materials from countries with unstable political systems, corrupt leadership, or opaque business environments.

Specialty metals are used in high-strength alloys, semiconductors, consumer electronics, batteries, armor plate, cell phones, and many more defense-specific and commercial applications. The United States lacks access to key minerals and materials that we need for our defense supply chains. There are concerns that corrupt business practices and manipulation of markets is one of the reasons that we have a lack of access to key raw materials, specifically rare earth elements.

China has a monopoly in the mining of key rare earth elements and minerals. China continues to not only involve themselves in the extraction industry, extraction of oxides, but the entire supply chain for rare earth elements and production of such things as advanced magnets which is essential in all modern defense electronics. Smart bombs, for example, have to have advanced magnets. China pulled that supply chain into China. Now is that corrupt? Certainly, there is manipulation. Is that something that we allowed to happen because we had our eye off the ball? I would argue that that is the case.

Compounding the tensions over access to specialty metals, many countries rich in natural resources take a stance of resource nationalism. Within the past decade, countries have attempted to leverage and manipulate extractive mining by threatening to impose extra taxes, reduce imports, reduce exports, nationalize mining operations and restrict licensing. Moreover, the countries themselves, notably China, have taken a more aggressive posture toward mineral resources and now compete aggressively with Western mining operators for extraction control.

We possess significant reserves of many specialty metals with an estimated value of $6.2 trillion. However, we currently import over $5 billion of minerals annually and are almost completely dependent on foreign sources for 19 key specialty metals.

Platinum is used in a wide variety of applications, but the commercial application we are all familiar with is the catalytic converter. But almost every modern engine has to have the platinum group of metals in it. Most of it is mined in South Africa. And I don’t want to go into a long, political discussion of the instability in South Africa, it is what it is. And we have to remember the role of the Chinese in that as well. The Chinese have established over the last 20, 30 years, excellent ties with countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Is that something that again we should note at this point, especially in this august committee?

We have to have a coherent strategic at the U.S. Government level to determine what those critical raw materials are. And then we need to act upon that to make sure that we have got secure access to them for our war fighters.

EDWARD C. CHOW, SENIOR FELLOW, ENERGY AND NATIONAL SECURITY PROGRAM, CENTER FOR STRATEGIC AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES

With the help of Western investments, Central Asia and the Caucasus today produce around 3.5% of global oil supply and hold around 2.5% of the world’s known proven reserves in oil. For comparison, this is equivalent to four times that of Norway and the United Kingdom combined. Another way of looking at this is to say the region produces around 8.5% of non-OPEC oil and holds around 9.5% of non-OPEC oil reserves. In other words, oil production in Central Asia has added significantly to global supply and will continue to do so in the future. In many ways, the energy future of the region lies as much or more in natural gas than in oil. Central Asia is estimated to hold more than 11% of the world’s proven gas reserves, mostly concentrated in Turkmenistan which has lagged behind Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan in attracting outside investments. The region currently produces less than 5% of global gas supply, so there is tremendous potential for growth.

Given its landlocked geography, Central Asia has to rely on long haul pipelines to take its oil and gas to market. Previously Soviet pipelines in the region almost all head to European Russia either to feed the domestic Soviet market or for trans-shipment to European markets.

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, China was just about to convert from a net oil exporter to net oil importer. It was slow off the mark in the race for Central Asian oil and gas. By the time it focused on this region, most of the large production opportunities have already been acquired by Western companies. From a Chinese point of view, they have been playing catch up ever since.

Today China is the second largest oil importer in the world and an increasingly important importer of gas. With stagnant Chinese domestic production and rapidly growing energy demand, China is destined to replace us as the world’s largest oil importer in a decade or so. Its companies have been investing in oil and gas around the world, including in neighboring Central Asia. Chinese companies now produce around 30% of Kazakhstan’s oil.

The next growing source of competition for Central Asia oil and gas is likely to come from India, which follows closely China in growth in oil and gas demand and consequently oil and gas imports. Indeed, as Chinese demographic growth slows and population ages, India’s energy demand is commonly forecasted to grow faster than China’s in a decade or so.

NEIL BROWN, NON-RESIDENT FELLOW, GERMAN MARSHALL FUND OF THE UNITED STATES

When I joined the Senate committee staff in 2005, we held a lot of hearings on these sorts of issues and at that time it was a lot of doom and gloom. Americans are doing what we do best which is changing the rules of the game through innovation in oil and gas and unconventional sources, efficiency, alternative energy, we are giving ourselves not only economic opportunities, but much more significant foreign policy flexibility and opportunities around the world, including in Central Asia which is important both for the issues that Ed mentioned in terms of the volume of oil and gas and other minerals the region has, but also for the strategic benefits and importance given that it sets above Iran, Pakistan, and Afghanistan.

The rising demand of emerging economies, particularly China, India, and in the Middle East, ironically, has over time really narrowed the margins in the global oil market which meant particularly in the mid-2000s that even small disruptions, attacks in the Niger Delta on Shell’s facilities could have an impact right here at home. I guess one good side of the recession is that demand slowed down so that we got a bit more of a window and also more recently the U.S. has boosted supply, again giving more flexibility. But that structural shift in markets has not changed. So we can expect more of the same, unfortunately, when the economy picks up.

JEFFREY MANKOFF, PH.D., DEPUTY DIRECTOR AND FELLOW, RUSSIA & EURASIAN PROGRAM, CENTER FOR STRATEGIC AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES

The discovery of new offshore oil and gas deposits in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea is one of the most promising global energy developments of the last several years. Handled wisely, these deposits off Israel and Cyprus, as well as potentially Lebanon, Gaza, and Syria, can contribute to the development and security for countries in the Eastern Mediterranean, and across a wider swathe of Europe. Handled poorly, these resources could become the source of new conflicts in what is an already volatile region.

According to the United States Geological Survey, the Levant Basin in the Eastern Mediterranean holds around 122 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, along with 1.7 billion barrels of crude oil.

The oil and gas resources of the Eastern Mediterranean sit, however, at the heart of one of the most geopolitically complex regions of the world. The Israeli-Palestinian conflict, tensions between Israel and Lebanon, the frozen conflict on Cyprus, and difficult relations among Turkey, the Republic of Cyprus, and Greece all complicate efforts to develop and sell energy from the Eastern Mediterranean. The Syrian civil war has injected a new source of economic and geopolitical uncertainty, and standing in the background is Russia, which is seeking to enter the Eastern Mediterranean energy bonanza, and to maintain its position as the major supplier of oil and gas for European markets.

Israel’s transformation into a significant energy producer is not without its challenges. Most immediate perhaps is the question of how Israel will sell its surplus gas on international markets. The most economical option, at least in the short term, would be the construction of an undersea pipeline allowing Israeli gas to reach European markets through Turkey. Such a pipeline from Israel to Turkey pipeline would be less expensive to build than new Liquefied Natural Gas facilities, would reinforce the recently strained political ties between Turkey and Israel, and would contribute to the diversification of Europe’s energy supplies by bringing a new source of non-Russian gas to Europe. Such a pipeline, however, would likely either run off the coasts of Lebanon and Syria, or have to go to Turkey through Cyprus. Both options are fraught with peril. Though Lebanon and Israel have not demarcated their maritime border, Beirut argues that Israel’s gas fields cross into Lebanese waters, and Hezbollah has threatened to attack Israeli drilling operations. Syria, of course, is in a state of near anarchy. In this perilous environment, finding investors willing to build a pipeline will be challenging, and even if built, such a pipeline would be difficult to secure. Going through Cyprus is also difficult, largely because of the difficult relationship between the Republic of Cyprus and Turkey. However, Cyprus’s own gas fields represent another potential source of conflict. Turkey has not recognized the Republic of Cyprus’s exclusive economic zone and in fact has pressured companies seeking to do business there, and recently also began its own exploratory drilling off of the de facto Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus without permission from the government in Nicosia. The revenues from Cypriot energy could benefit communities on both sides of the island, but only if a political agreement can be worked out in advance. The major alternative to a pipeline from Israel to Turkey would be to build an LNG, a Liquefied Natural Gas facility to liquefy gas for sale to markets in Asia and the Middle East. Russia, in particular, backs this idea. The push to build new LNG facilities though is only one way in which Moscow and its energy companies are seeking a larger role in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Russian companies are also interested in Israel’s much larger Leviathan field, as well as in the offshore oil and gas off of Lebanon.

Russia will remain the principal supplier of Europe’s gas for many years. The potential volumes from the Eastern Mediterranean could bolster European energy security around the margins, but they are not sufficient not to change this fundamental reality. For that reason, Washington’s main objective in the Eastern Mediterranean should be less about Europe and more about ensuring that energy does not become a source of new resource conflicts, whether between Israel and its neighbors or over Cyprus.