Preface. The founder of the War on Drugs in the U.S., Harry Anslinger, wanted to build as large a bureaucracy as possible. But a war on narcotics alone—cocaine and heroin, outlawed in 1914—wasn’t enough. They were used only by a tiny minority, and you couldn’t keep an entire department alive on such small crumbs. Anslinger needed more. He scoured papers for other drugs and hit upon marijuana that could be banned to gain a larger staff, budget, and prestige. To bolster his arguments, he wrote 30 doctors about the harms of marijuana, and all but one wrote back that it would be wrong to ban it and was widely misrepresented in the press. So he ignored them and went with the only doctor who thought marijuana was evil, as he continued to do so throughout his career with other drugs as well. For years, doctors kept approaching him with evidence marijuana was fine and he told them they were “treading on dangerous ground” and should watch their mouths.

The Harrison act making Anslinger’s bureaucracy possible had a giant loophole: doctors were allowed to prescribe heroin and other drugs to their patients if they thought it was in their patients best interest. The Supreme Court even ruled in the doctors favor, stating that this act didn’t give the government authority to punish doctors who did prescribed drugs. But Anslinger ignored this ruling and arrested 20,000 doctors across the nation, and many of them were heavily fined as well.

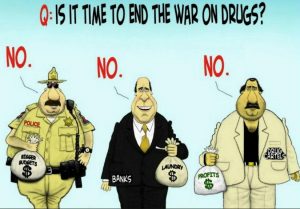

While Harry Anslinger was raging against the Mafia in public, he was, in fact, secretly working for them. The Mafia funded Harry Anslinger to launch his crusade because they wanted the drug market all to themselves. It was the scam of the century.

The main reason Anslinger gave for banning drugs was that the blacks, Mexicans, and Chinese were using these chemicals, forgetting their place, and menacing white people.

More than 50% of Americans have breached the drug laws. Where a law is that widely broken, you can’t possibly enforce it against every lawbreaker. The legal system would collapse under the weight of it. So you go after the people who are least able to resist, to argue back, to appeal—the poorest and most disliked groups. In the United States, they are black and Hispanic people, with a smattering of poor whites.

The war on drugs was clearly a bad idea — we know that Prohibition made Al Capone and other violent gangsters rich and corrupted other institutions as well. Before prohibition people drank wine and beer, after they drank hard liquor and deadly moonshine as mafias made alcohol more potent and easier to smuggle. Likewise, coca leaves were turned into crack cocaine, opium into heroin, marijuana into hashish.

The drug war has corrupted police world-wide, led to hundreds of thousands of deaths of innocent people caught in the crossfire and corrupted politicians.

There are nations that have “legalized” heroin. It is not sold openly to everyone, but administered in government clinics, where social services and treatment programs are available. An astounding number of heroin addicts are able to quit. Crimes and mafias drop dramatically. AIDS and other diseases spread by needles decline as well. This has been tried with great success in Vancouver Canada, Great Britain, Switzerland, Portugal, Amsterdam, and Uruguay (among others). States that have legalized marijuana have seen no ill-effects — bad driving and traffic accidents have not gone up.

Hari makes the case that other drugs can and should be legalized as well. This is a very comprehensive overview. There is even a chapter on Joe Arpaio and how almost Nazi level women’s tent cities (no A/C in 130 F heat for example) only drove them into addiction further when they get out.

To stop the drug war, go to Hari’s site www.chasingthescream.com/getinvolved — also see www.facebook.com/chasingthescream

Alice Friedemann www.energyskeptic.com Author of Life After Fossil Fuels: A Reality Check on Alternative Energy; When Trucks Stop Running: Energy and the Future of Transportation”, Barriers to Making Algal Biofuels, & “Crunch! Whole Grain Artisan Chips and Crackers”. Women in ecology Podcasts: WGBH, Planet: Critical, Crazy Town, Collapse Chronicles, Derrick Jensen, Practical Prepping, Kunstler 253 &278, Peak Prosperity, Index of best energyskeptic posts

***

Johann Hari. 2016. Chasing the Scream: The First and Last days of the War on Drugs.

The pledge to wage “relentless warfare” on drugs was first made in the 1930s.

From his first day in office, Harry Anslinger had a problem, and everybody knew it. He had just been appointed head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics—a tiny agency, buried in the gray bowels of the Treasury Department in Washington, D.C.—and it seemed to be on the brink of being abolished. This was the old Department of Prohibition, but prohibition had been abolished and his men needed a new role, fast. As he looked over his new staff just a few years before his pursuit of Billie began, he saw a sunken army who had spent fourteen years waging war on alcohol only to see alcohol win, and win big. These men were notoriously corrupt and crooked—but now Harry was supposed to whip them into a force capable of wiping drugs from the United States forever.

And that was only the first obstacle. Many drugs, including marijuana, were still legal, and the Supreme Court had recently ruled that people addicted to harder drugs should be dealt with by doctors, not bang-’em-up men like Harry.

He pledged to eradicate all drugs, everywhere—and within thirty years, he succeeded in turning this crumbling department, with these disheartened men, into the headquarters for a global war that would last for a hundred years and counting.

Giovanni spoke. He said he was being forced to pay protection money by a man called “Big Mouth Sam,” one of the thugs belonging to a group called the Mafia that had come to the United States from Sicily and remained hidden amidst the Italian immigrants. The Mafia, Giovanni told Harry, were engaged in all sorts of crimes, and people on the railroad were being charged a “terror tax”—you gave the Mafia money or else you ended up in a hospital bed like this, or worse.

After that, Anslinger became obsessed with the Mafia, at a time when most Americans refused to believe it even existed. This is hard for us to understand today, but the official position of every official in U.S. law enforcement until the 1960s—from J. Edgar Hoover on down—was that the Mafia was a preposterous conspiracy theory, no more real than the Loch Ness Monster. They reacted the way we would now if a law enforcement agent preached Trutherism, or Birtherism, or the belief that Freemasons are secretly manipulating world events: with bafflement at the idea that anyone could believe something so silly. But Harry had glimpsed the Mafia in the flesh, and he was convinced that if he followed the trail from Big Mouth Sam to the thugs above him and the thugs above them, he would be led to a vast global web, and perhaps even to an “invisible world-wide government” secretly controlling events. He soon started keeping every scrap of information he could find on the Mafia, no matter how small or how trivial the source.

At the very end of the war, as it was becoming clear to everyone that the Germans had lost, Harry was sent on his most important mission so far: to take a secret message to the defeated German dictator. The way he later told the story, Harry was dispatched to the small Dutch town of Amerongen, where the Kaiser was holed up in a castle and planning to abdicate. Anslinger’s job was to pose as a German official and convey a message from President Woodrow Wilson: Don’t do it. The United States wanted the Kaiser to retain the imperial throne, to prevent the rise of the “revolution, strikes and chaos” it feared would follow from his sudden departure.

Anslinger managed to get the message through—but it was too late. The decision had been made. The Kaiser quit. For the rest of his life, Anslinger believed that if he had gotten the president’s plea through only a little earlier, “a decent peace might have been written, forestalling any chance for a future Hitler gaining power, or a Second World War erupting.

But what shook Harry most was the effect of the war not on the buildings but on the people. They seemed to have lost all sense of order. Starving, they had begun to riot; the cavalry had been sent to charge against them, and entire streets were on fire. Harry was standing in a hotel lobby in Berlinwhen Socialist revolutionaries suddenly fired their machine guns into the lobby, and blood from a bystander splattered onto his hands. Civilization, he was beginning to conclude, was as fragile as the personality of that farmer’s wife back in Altoona. It could break. After this, and for the rest of his life, Harry retained a deep sense that American society could collapse into wreckage just as quickly as Europe’s had.

Harry announced to his bosses that there was a way to make prohibition work: Use maximum force. Send the navy to hunt down smugglers along the coasts of America. Ban the sale of alcohol for medical purposes. Massively increase prison sentences for alcohol dealers until they were all locked up. Wage war on booze until it was only a memory.

A war on narcotics alone—cocaine and heroin, outlawed in 1914—wasn’t enough. They were used only by a tiny minority, and you couldn’t keep an entire department alive on such small crumbs. He needed more.

He found stories in the newspapers that intrigued him. They had headlines like the one in the July 6, 1927, edition of the New York Times: MEXICAN FAMILY GO INSANE. It explained: “A widow and her four children have been driven insane by eating the Marihuana plant, according to doctors who say there is no hope of saving the children’s lives and that the mother will be insane for the rest of her life.” The mother had no money to buy food, so she decided to eat some marijuana plants that had been growing in their garden. Soon after, “neighbors, hearing outbursts of crazed laughter, rushed to the house to find the entire family insane.” Harry had long dismissed cannabis as a nuisance that would only distract him from the drugs he really wanted to fight. He insisted it was not addictive, and stated “there is probably no more absurd fallacy” than the claim that it caused violent crime. But almost overnight, he began to argue the opposite position. Why? He believed the two most-feared groups in the United States—Mexican immigrants and African Americans—were taking the drug much more than white people. This led to a nightmarish vision of where this could lead. He had been told, he said, of “colored students at the University of Minn[sota partying with female students (white) and getting their sympathy with stories of racial persecution. Result: pregnancy.

He wrote to 30 scientific experts asking a series of questions about marijuana, and 29 wrote back saying it would be wrong to ban it, and that it was being widely misrepresented in the press. Anslinger decided to ignore them and quoted instead the one expert who believed it was a great evil that had to be eradicated. On this basis, Harry warned the public about what happens when you smoke this weed. First, you will fall into “a delirious rage.” Then you will be gripped by “dreams . . . of an erotic character.” Then you will “lose the power of connected thought.” Finally, you will reach the inevitable end point: “Insanity.” You could easily get stoned and go out and kill a person, and it would all be over before you even realized you had left your room, he said, because marijuana “turns man into a wild beast.

A doctor called Michael V. Ball got in touch with Harry to counter this view, saying he had used hemp extract as a medical student and it only made him sleepy. He suspected that the claims circulating about the drug couldn’t possibly be true. Maybe, he said, cannabis does drive people crazy in a tiny number of cases, but his hunch was that anybody reacting that way probably had an underlying mental health problem already. He implored Anslinger to fund proper lab studies so they could find out the truth. Anslinger wrote back firmly. “The marihuana evil can no longer be temporized with,” he explained, and he would fund no independent science, then or ever.

For years, doctors kept approaching him with evidence that he was wrong, and he began to snap, telling them they were “treading on dangerous ground” and should watch their mouths. Instead, he wrote to police officers across the country commanding them to find him cases where marijuana had caused people to kill—and the stories started to roll in.

The defining case for Harry, and for America, was of a young man named Victor Lacata. He was a 21-year-old Florida boy known in his neighborhood as “a sane, rather quiet young man” until—the story went—the day he smoked cannabis. He then entered a “marihuana dream” in which he believed he was being attacked by men who would cut off his arms, so he struck back, seizing an axe and hacking his mother, father, two brothers, and sister to pieces.

Many years later, the law professor John Kaplan went back to look into the medical files for Victor Lacata. The psychiatrists who examined him said he had long suffered from “acute and chronic” insanity. His family was full of people who suffered from similarly extreme mental health problems—three had been committed to insane asylums—and the local police had tried for a year before the killings to get Lacata committed to a mental hospital, but his parents insisted they wanted to look after him at home. The examining psychiatrists thought his cannabis use was so irrelevant that it wasn’t even mentioned in his files.

The most frightening effect of marijuana, Harry warned, was on blacks. It made them forget the appropriate racial barriers—and unleashed their lust for white women. Of course, everyone spoke about race differently in the 1930s, but the intensity of Harry’s views shocked people even then.

Many white Americans did not want to accept that black Americans might be rebelling because they had lives like Billie Holiday’s—locked into Pigtowns and banned from developing their talents. It was more comforting to believe that a white powder was the cause of black anger, and that getting rid of the white powder would render black Americans docile and on their knees once again. (The history of this would be traced years later in Michelle Alexander’s remarkable book The New Jim Crow.)

The arguments we hear today for the drug war are that we must protect teenagers from drugs, and prevent addiction in general. We assume, looking back, that these were the reasons this war was launched in the first place. But they were not.

The main reason given for banning drugs—the reason obsessing the men who launched this war—was that the blacks, Mexicans, and Chinese were using these chemicals, forgetting their place, and menacing white people.

It took me a while to see that the contrast between the racism directed at Billie and the compassion offered to addicted white stars like Judy Garland was not some weird misfiring of the drug war—it was part of the point.

Harry told the public that “the increase [in drug addiction] is practically 100 percent among Negro people,” which he stressed was terrifying because already “the Negro population . . . accounts for 10% of the total population, but 60% of the addicts.” He could wage the drug war—he could do what he did—only because he was responding to a fear in the American people.

In the run-up to the passing of the Harrison Act, the New York Times ran a story typical of the time. The headline was: NEGRO COCAINE “FIENDS” NEW SOUTHERN MENACE. It described a North Carolina police chief who “was informed that a hitherto inoffensive negro, with whom he was well-acquainted, was ‘running amuck’ in a cocaine frenzy [and] had attempted to stab a storekeeper . . . Knowing he must kill this man or be killed himself, the Chief drew his revolver, placed the muzzle over the negro’s heart, and fired—‘intending to kill him right quick,’ as the officer tells it, but the shot did not even stagger the man.” Cocaine was, it was widely claimed in the press at this time, turning blacks into superhuman hulks who could take bullets to the heart without flinching. It was the official reason why the police across the South increased the caliber of their guns.

But there was another racial group that also had to be kept down, Harry believed. In the mid-nineteenth century, Chinese immigrants had begun to flow into the United States, and they were now competing with white people for jobs and opportunities. Worse still, Harry believed they were competing for white women. He warned that with their “own special Oriental ruthlessness,” the Chinese had developed “a liking for the charms of Caucasian girls . . . from good families.” They lured these white girls into their “opium dens”—a tradition they had brought from their home country—got the girls hooked, and then forced them into acts of “unspeakable sexual depravity” for the rest of their lives. Anslinger described their brothels in great detail: how the white girls removed their clothes slowly, the “panties” they revealed, how slowly they kissed the Chinese, and what came next . .

Once the Chinese dealers got you hooked on opiates, they would laugh in your face and reveal the real reason they sell junk: it was their way of making sure that “the yellow race would rule the world.”

At first, ordinary citizens had taken matters into their own hands against this Yellow Peril. In Los Angeles, 21 Chinese people were shot, hanged, or burned alive by white mobs. In San Francisco, officials tried to forcibly move everyone in Chinatown into an area reserved for pig farms and other businesses that were designated as dirty and disease-ridden, until the courts ruled the policy was unconstitutional. So the authorities did the next best thing: they launched mass raids on Chinese homes and businesses, saying it was time to stop their opium use.

Harry Anslinger did not create these underlying trends. His genius wasn’t for invention: it was for presenting his agents as the hand that would steady all these cultural tremblings.

The drug war was born in the United States—but so was the resistance to it. Right at the start, there were people who saw that the drug war was not what we were being told. It was something else entirely. Harry Anslinger wanted to make sure we would never put these pieces together.

In Los Angeles, there was a doctor in the early 1930s named Henry Smith Williams who shared all of Harry Anslinger’s hatreds. He said that addicts were “weaklings” who should never have been brought into the world and wrote that “the idea that every human life has genuine value . . . and therefore is something to be treasured, is an absurd banality. The world would be far better off if forty percent of its inhabitants had never been born.” In his view, drugs led only to destruction, and nobody should take them, ever.

Henry’s brother Edward on the other hand, couldn’t bear to see addicts suffering—not when he knew there was a way to stop their pain. That is why he had helped to set up this clinic—and why he was about to be ruined. “Can the doctor do nothing? Oh yes, the doctor knows just what should be done,” he explained. “He knows that he has but to write a few words on the prescription blank that lies at his elbow, and the patient, tottering to the nearest drug store, will receive the remedy that would restore him miraculously to a semblance of normality and the actuality of physical and mental comfort.” He can provide a legal prescription for the drug to which the patient has become addicted. It will not damage his body: all doctors agree that pure opiates do no harm to the flesh or the organs. The patient, after taking the drug, will become calm. He will be able to function again. He will be able to work, or support a family, or love.

Edward was one of the 20,000 doctors illegally arrested for prescribing drugs. As he watched his brother’s career being destroyed by the police, Henry remembered something that now seemed to him, for the first time, to be significant. Before it became a crime to sell drugs, he had many patients who used them—but things had been very different then. They had bought their opiates, including morphine and heroin, at a low price from their local pharmacist. They were sold in bottles as “remedies” or “little helpers,” for everything from a chest infection to the blues.

There were many women who used opiates in the form of “syrups” every day who, he said, “would have gone on their hands and knees to pray for a lost soul had they seen cigarette stains on the fingers of a daughter.

Just as a large majority of drinkers did not become alcoholics, a large majority of users of these products did not become drug addicts. They used opiates as “props for the unstable nervous system,” like a person who drinks wine at the end of a stressful day at work.

A small number did get hooked—but even among the addicted, the vast majority continued to work and maintain relatively normal lives. An official government study found that before drug prohibition properly kicked in, three quarters of self-described addicts (not just users—addicts) had steady and respectable jobs. Some 22% of addicts were wealthy, while only 6% were poor. They were more sedate as a result of their addiction, and although it would have been better for them to stop, they were rarely out of control or criminal.

Doctors saw the results of the policy changes. “Here were tens of thousands of people, in every walk of life, frantically craving drugs that they could in no legal way secure,” Henry wrote. “They craved the drugs, as a man dying of thirst craves water. They must have the drugs at any hazard, at any cost. Can you imagine that situation, and suppose that the drugs will not be supplied? . . . [The lawmakers] must have known that their Edict, if enforced, was the clear equivalent of an order to create an illicit drug industry. They must have known that they were in effect ordering a company of drug smugglers into existence.” The drug dealer could now charge extortionate prices. In the pharmacies, morphine had cost two or three cents a grain; the criminal gangs charged a dollar.

The world we recognize now—where addicts are often forced to become criminals, in a desperate scramble to feed their habit from gangsters—was being created, for the first time. The Williams brothers had watched as Anslinger’s department created two crime waves. First, it created an army of gangsters to smuggle drugs into the country and sell them to addicts. In other words: while Harry Anslinger claimed to be fighting the Mafia, he was in fact transferring a massive and highly profitable industry into their exclusive control. Second, by driving up the cost of drugs by more than 1,000%, the new policies meant addicts were forced to commit crime to get their next fix. “How was the average addict—revealed by the official census as an average person—to secure 10 or 15 dollars a day to pay for the drug he imperatively needed?” Henry Smith Williams asked. “Can you guess the answer? The addict could not get such a sum by ordinary means. Then he must get it by dubious means—he must beg, borrow, forge, steal.” The men, he wrote, usually became thieves; the women often became prostitutes.

When the Harrison Act banning heroin and cocaine was written in 1914, it contained a very clear and deliberately designed loophole. It said that doctors, vets, and dentists had the right to continue giving out these drugs as they saw fit—and that addicts should be dealt with compassionately in this way. Yet the loophole was tossed onto the trash heap of history, as if it didn’t exist—until Edward Williams decided to dig it out and act on it. He helped to build a free clinic for addicts, and he volunteered his own time there. He wrote his prescriptions for whoever needed them. And he waited to see the results. Even he was surprised by what he saw. Patients who had come in as unemployed physical wrecks were able, slowly and steadily, to go back to work, support their families, and look after themselves again, just as they had before drugs were criminalized. The order and calm that had existed before narcotics prohibition started to return to their neighborhoods. The mayor of Los Angeles came out and celebrated the clinic as a great gift to the city, and the local federal prosecutor announced that these clinics accomplished “more good . . . in one day than all the prosecutions in one month.

After the clinic in Los Angeles closed and doctors like Edward Williams were busted, almost all the addicts lost their jobs31 and were reduced once again to constant scrambling for the money for a fix. They fell into crime and homelessness, and dozens of them died. The bureau was defying the clear ruling of the Supreme Court33 that the Harrison Act allowed doctors to prescribe to addicts, but “the Supreme Court has no army to enforce its decisions,” the press noted with a shrug.

Some 20,000 doctors were charged with violating the Harrison Act alongside Edward Williams, and 95% were convicted. Most were charged massive fines, but some faced five years in prison for each and every prescription written. In many places, horrified juries refused to convict, because they could see the doctors were only treating the sick as best they could. But Anslinger’s crackdown continued with full force.

The doctors were so emotional, Harry insisted, because they were corrupt. Don’t be fooled: they only wanted the money from drug addicts’ prescriptions. They were missing the hard cash, he said, and nothing more.

Besides, he said, he had proof that his way worked. Since the bureau’s crackdown began, the number of addicts had fallen dramatically, to just 20,000 in the whole country. Years later, a historian named David Courtwright put in a Freedom of Information request to find out how this figure was calculated—and found that it was simply made up. The Treasury Department’s top officials had privately said it was “absolutely worthless.

Henry Smith Williams urged the public to ask: Why would gangsters pay the cops to enforce the drug laws harder? The answer, he said, was right in front of our eyes. Drug prohibition put the entire narcotics industry into their hands. Once the clinics were closed, every single addict became a potential customer and cash cow.

Harry worked very hard to keep the country in a state of panic on the subject of drugs so that nobody would ever again see these logical contradictions. Whenever people did point them out, he had them silenced.

Henry Smith Williams was never the same after these experiences. Before, he saw the majority of human beings as feeble dimwits who barely deserve life. But he started to argue that humans didn’t have to be engaged in a brutal Darwinian war of survival after all; instead, we can choose kindness in place of crushing the weak. He spent his remaining years setting up a group to campaign for an end to the drug war, but Anslinger’s men wrote to everyone who expressed an interest in it, warning them it was a “criminal organization” that was “in trouble with Uncle Sam.” Henry Smith Williams died in 1940. Drug Addicts Are Human Beings remained out of print and largely forgotten for the rest of Anslinger’s life, and ours.

The book contained a prediction. If this drug war continues, Henry Smith Williams wrote, there will be a five-billion-dollar drug smuggling industry in the United States in fifty years’ time. He was right almost to the exact year.

While Harry Anslinger was shutting down all the alternatives to the drug war in the United States, across the rest of the world, drugs were still being sold legally. Over the next few decades, this began to end—and by the 1960s, they were banned everywhere. At first, I assumed this was because every country had its own local fears and its own local Anslingers.

But the truth is that Anslinger brought every other nation into line. He issued letters with orders all over the world—including to my country, Britain. He acted as the first “drug czar” not just for the United States, but for the world.

Once the doctors were whipped into line, there was one thing left that puzzled Harry. He was doing all the right things. He was cracking down on addicts and doctors and dealers. Yet Baltimore was not becoming a drug-free paradise.

The Communists, he declared, were clearly flooding America with drugs, as part of a “cold, calculated, ruthless, systematic plan to undermine” America. Harry warned sternly, every addict was not only a criminal and a thug. He was also a potential Communist traitor.

His agents told him none of these claims were true. One of them later gave an interview in which he said: “There was no evidence for Anslinger’s accusations, but that never stopped him.” But once again, Harry had tapped into the deepest fears of his time and ensured that they ran right through his department, swelling his budget as they went. Whatever America was afraid of—blacks, poor people, Communists—he showed how the only way to deal with the fear was to deal with drugs, his way.

By conjuring this Communist conspiracy into existence in the 1950s, Harry found a way to turn his failure into a reason to escalate the war. Drug prohibition would work—but only if it was being done by everyone, all over the world. So he traveled to the United Nations with a set of instructions for humanity: Do what we have done. Wage war on drugs. Or else. Of all Harry’s acts, this was the most consequential for us today.

Thailand flatly refused to ban opium smoking, on the grounds that it was a long-standing tradition in their country, and less harmful than prohibition. So Harry started to twist arms. One of his key lieutenants, Charles Siragusa, boasted: “I found that a casual mention of the possibility of shutting off our foreign aid programs, dropped in the proper quarters, brought grudging permission for our operations almost immediately.” Later, leaders were threatened with being cut off from selling any of their countries’ goods to the United States.

Whenever any representative of another country tried to explain to him why these policies weren’t right for them, Anslinger snapped: “I’ve made up my mind—don’t confuse me with the facts.” And so Thailand caved. Britain caved. Everyone—under threat—caved in the end. The United States was now the most powerful country in the world, and nobody dared defy them for long. Some were more willing than others. Pretty much every country has its own minority group, like African Americans, whom it wants to keep down. For many, it was a good excuse. And pretty much every country had this latent desire to punish addicts

His private files started to warn in frantic tones that addicts were “contagious,” and that any one of us could be infected if they were not immediately “quarantined.

Although nobody was told at the time, Harry in fact had a mental breakdown and had to be hospitalized. When he returned, his paranoia only seemed to have grown. He saw enemies and plots and secret attempts to control the entire world around every corner. How could a man like this have persuaded so many people?

They wanted to be persuaded. They wanted easy answers to complex fears. The public wanted to be told that these deep, complex problems—race, inequality, geopolitics—came down to a few powders and pills, and if these powders and pills could be wiped from the world, these problems would disappear.

This is a logic that keeps recurring throughout human history, from the Crusades to the witch hunts to the present day. It’s hard to sit with a complex problem, such as the human urge to get intoxicated, and accept that it will always be with us, and will always cause some problems (as well as some pleasures). It is much more appealing to be told a different message—that it can be ended. That all these problems can be over, if only we listen, and follow.

After Harry finally retired from running the bureau—with a little nudge from JFK—they discovered something odd about Harry’s paranoia. It turns out it had been pointed in every direction except where it would have been deserved—at his own department. Immediately after he finally stood down, an investigation by a special team from the Internal Revenue Service found that the bureau was not free from corruption, leading historian John McWilliams to claim that, “the bureau itself was actually the major source of supply and protector of heroin in the United States.

Years later, in 1970, Playboy magazine arranged a roundtable debate of the drug laws and invited him to take part. For the first time since he sat down with Henry Smith Williams in the 1930s, Harry Anslinger was forced to defend his arguments against articulate opponents. They included the psychiatrist Dr. Joel Fort, the lawyer Joseph Oteri, and the poet laureate of narcotics, William Burroughs.

Anslinger started to try to compete with their world of factual claims, saying: “I challenge you to name one doctor who has reported a beneficial effect of marijuana, outside of the backward areas of the world.” He was immediately answered with names: Dr. Lloyd J. Thompson, professor of psychiatry at Bowman Gray School of Medicine, and George T. Stocking, one of Britain’s leading psychiatrists. Again, Anslinger had no response. This kept happening in a strange fox-trot of debunking. Anslinger asserted; the experts rebutted; Anslinger fell silent. When feeling met fact, he was stumped. And then Anslinger snapped. He started calling everybody at the table around him “utterly monstrous” and said they were talking “vicious tripe” and must have a “disordered mind.” Then he compared them to Adolf Hitler, and finally spluttered: “We’ve been hearing some of the most ridiculous statements that have ever been made.

Dr. Fort looked over at Anslinger’s vast bald head and replied. “You have led this country to treat scientific questions,” he said, “the way such matters were handled in the Middle Ages.

The first man to really see the potential of drug dealing in America was a gangster named Arnold Rothstein—and I slowly realized it was possible to piece him back together in quite a lot of detail. He was so egotistical he actually invited journalists to write about him—and he was so powerful he didn’t worry about the police reading it. He owned them. There have been a number of biographies written of him, and even more important, I found out that after he died, his wife wrote a detailed memoir of her life with him, explaining exactly what he was like, in lush novelistic detail. There was only one problem. Every copy of his wife’s memoir seemed to have disappeared. Even the copy at the New York Public Library had vanished sometime in the 1970s. I eventually tracked down what seems to be the only remaining copy, in the Library of Congress,

Everybody in New York City knew that Rothstein could have you killed just by snapping his fingers—and that he had bought so many NYPD cops and politicians that he would never be punished for it.

“There are two million fools to one brainy man.” He was the brainy man, and he was going to get his due from the fools. And the Brain—as he now insisted on being called—soon discovered the greatest truth of gambling: the only way to win every time is to own the casino. So he set up a series of underground gambling dens across New York City, and when they got busted, one after another, he invented the “floating” craps game: a never-ending craps shoot that skipped from shadowy venue to dusky basement across the island. He carried the cash on him, up to a hundred thousand dollars at a time, and he obsessively counted the money, by hand, again and again.

At the racetrack, he would pay jockeys to throw the race, and gradually, year by year, he took this to a higher level. The bets got bigger and his winnings got more improbable, until he finally reached the biggest, most watched, most adrenaline-soaked game in America: the World Series. Fifty million Americans were following the result in 1919 when, against all the odds and every prediction, the Cincinnati Reds beat the far-and-away favorites, the White Sox. Long after the gasps were silent and the stadium was full only of echoes, the reason emerged: Rothstein had paid eight White Sox players to throw the match. All eight players were charged with fraud—and all were mysteriously acquitted.

Arnold was handed two of the largest industries in America, tax-free. He immediately spotted that the prohibition of booze and drugs was the biggest lottery win for gangsters in history. There will always be large numbers of people who want to get drunk or high, and if they can’t do it legally, they will do it illegally.

“Prohibition is going to last a long time and then one day it’ll be abandoned,” Rothstein told his associates. “But it’s going to be with us for quite a while, that’s for sure. I can see that more and more people are going to ignore the law . . . and we can make a fortune meeting this need.

Under prohibition, dealers were starting to discover, you can sell whatever crap you want: Who’s going to complain to the police that they were poisoned by your illicit booze? Outbreaks of mass alcohol poisoning spread across America: in one incident alone, 500 people were permanently crippled in Wichita, Kansas. But the market for illegal alcohol would live on for thirteen years, and then Franklin Roosevelt—desperate for new sources of tax revenue—would make it legal again in 1933. The greater gift, Rothstein saw, was in the market for drugs. They, surely, would stay banned far into the future.

He sent his men to buy heroin in bulk in Europe, where factories could still legally make it, shipped it over, and then distributed it to street sellers across New York and beyond. For his system to work, Rothstein had to invent the modern drug gang. There had been gangs in New York City for generations, but they were small-time hoodlums who spent most of their energy beating each other up. Arnold’s gangs were as disciplined as military units, and he made sure they had only one passion: the bottom line. That is how, by the mid-1920s, Rothstein and his new species of New York gang controlled the entire trade in heroin and cocaine on the Eastern seaboard of the United States.

Arnold soon discovered that when you control the massive revenue offered by the drug industry, individual police and politicians are easy to buy. His profit margins were so vast he could outbid the salaries cops earned from the state. “The police,” a journalist wrote in 1929, “were as gracious to him as they were to a police commissioner.” This is why every time Arnold Rothstein was caught committing violence, the charges “mysteriously” vanished.

Arnold tamed the police with an approach that, years later, would be distilled by his successors, the Mexican drug cartels, into a single elegant phrase: plata o plomo. Silver or lead.

When two detectives, John Walsh and Josh McLaughlin, broke into one of Rothstein’s illegal dens one night, he shot at them, suspecting they were robbers. The judge dismissed the case. A journalist asked: What’s “a little pistol practice with policemen as targets” when you are Arnold Rothstein?

When a popular product is criminalized, it does not disappear. Instead, criminals start to control the supply and sale of the product. They have to get it into the country, transport it to where it’s wanted, and sell it on the street. At every stage, their product is vulnerable. If somebody comes along and steals it, they can’t go to the police or the courts to get it back. So they can only defend their property one way: by violence. But you don’t want to be having a shoot-out every day—that’s no way to run a business. So you have to establish a reputation: a reputation for being terrifying. People must believe that you are so violent and brutal that they are too afraid to even try to pick a fight with you. You can only establish that reputation with attention-grabbing acts of brutality. The American sociologist Philippe Bourgois would give this process a name: “a culture of terror.” But the first person to notice and begin to articulate this dynamic was a half-drunk, nicotine-encrusted tabloid journalist, Donald Henderson Clarke, whose beat was to hang out in bars, from Midtown to the Bowery, with Rothstein and his fellow thugs. It is hard, he wrote, to convey “the fear with which Rothstein was regarded. Get in bad with a Police Commissioner, or a District Attorney, or a Governor, or anyone like that and you could figure out with a fair degree of certainty what might happen to you on the basis of what you had done.

Rothstein’s domination of the East Coast drug trade shattered as that trigger was pulled—from that moment on, drug dealers would be engaged in a constant conflict to control the distribution of drugs.

Arnold Rothstein is the start of a lineup of criminals that runs through the Crips and the Bloods and Pablo Escobar to Chapo Guzman—each more vicious because he was strong enough to kill the last. As Harry Anslinger wrote in 1961: “One group rose to power over the corpses of another.

Like Rothstein, Harry Anslinger is reincarnated in ever-tougher forms, too. Before this war is over, his successors were going to be deploying gunships along the coasts of America, imprisoning more people than any other society in human history, and spraying poisons from the air across foreign countries thousands of miles away from home to kill their drug crops.

There was once only one Arnold Rothstein in New York City. In the seven decades of escalating warfare ever since, there has come to be an Arnold Rothstein on every block in every poor neighborhood in America.

Chino’s crack came in white slivers that looked like chips of soap. At first, he stashed them in his mouth, but they made his cheeks and tongue go numb. Then he held them in his hand, but they started to dissolve, and nobody wanted to buy that. So he learned you had to get creative. He sometimes stuck them under a nearby parked car, attached to a magnet. Later, he got a collar for his pit bull, Rocky, and kept the crack in his collar—“so Rocky sold crack, too,” he laughed. But on that day—and the endless days like it—they were in his cap and up for sale. Their crew was part of a wider network called Brooklyn’s Most Wanted, who controlled the Thirties in Flatbush. He got his drugs from Peter, a guy in his twenties from Chino’s block, and he answered to him. Peter first approached him when Chino was thirteen, asking if he wanted to make a lot of cash. He explained: you take the bags, you work the corner, you keep up to $500 a week. After that, everybody knew he was under Peter’s protection. You couldn’t touch him without retaliation from Peter, and he was one of the three or four biggest dealers between Utica and Flatbush. It meant Chino had power, and respect, and a name, and as much freedom from fear as he would ever get.

To protect this way of life, you have to be terrifying. As we learned under Rothstein, you can’t go to the police to protect your property or your trade. You have to defend it yourself, with guns and testosterone. If you ever crack and show some flicker of compassion, he tells me years later, “everybody’s going to fucking rob you . . . They’ll just move in on your turf, take over your block, do whatever they want to you. You have to be fucked up to survive in this fucked-up paradigm . . . You got to be violent to not have violence done to you . . . You set examples. You make examples out of people. Some of them are completely justified and called for. A lot of them are not.

So the crew shot at trees, shot in the air, killed animals. Sometimes Chino would shoot in the direction of people—rival crews he needed to scare shitless. He will tell me that his bullets never hit them. He will also tell me there are things he can never tell anyone.

Two of their rival gangs were called the Autobots and the Decepticons, after the Transformer toys that were popular at the time,

One time, some older men arrived on the block to try to claim it as theirs. Chino remembers it this way: “We had some cats come through . . . some older cats . . . we welcomed them, smoked with them, laughed with them. Basically, they were trying to son us [that is, treat them like kids—like their sons]—tell us what to do as if we didn’t have our own set. Some altercation happened between them and one of my soldiers, and before you know it, we was beating their ass . . . We jumped them . . . and beat the shit out of them. We hit them with bottles, garbage cans, and we let them run out of the neighborhood and told them to never come back.” About this need to defend his teenage crew against older aggressors, he says: “It’s almost like in the animal kingdom—it’s no different in terms of how our minds are . . . They thought they were the bigger, older lions . . . but we’re not necessarily lions, we’re like packs of hyenas. If you’re going to play by animal kingdom rules, you got to know the right animal.

Chino had to deal with Smokie. He had pulled the crew into danger and then vanished. When he skulked toward Chino after it was all over, he claimed he had run to get a gun to defend them—but Chino couldn’t make allowances for cowardice, not here. The crew took him to the 235 Park nearby, a grassy patch, and poured water on his shirt. Then Chino took off his belt, and he lashed Smokie, thirty-one times. That was the standard first phase of punishment for cowardice. Then he had to embark on the second phase. He had to go find the opposing set and slash one of them. Smokie staggered off—but something went wrong. He didn’t slash a rival. Terrorized and half-crazed and hyped, he looked for anyone he could attack—and he slashed an old man in a store, which isn’t what Chino wanted at all. Soon he was back in prison. Chino was furious: the point he needed to be made was that his set was strong and nobody should ever try and fuck with them or take their drugs or mock their status. By attacking an old person, he says, he “actually made us look weaker.

When we hear about “drug-related violence,” we picture somebody getting high and killing people. We think the violence is the product of the drugs. But in fact, it turns out this is only a tiny sliver of the violence. The vast majority is like Chino’s violence—to establish, protect, and defend drug territory in an illegal market, and to build a name for being consistently terrifying so nobody tries to take your property or turf.

Just as the war on alcohol created armed gangs fighting to control the booze trade, the war on drugs has created armed gangs fighting and killing to control the drug trade. The National Youth Gang Center has discovered that youth gangs like the Souls of Mischief are responsible for between 23 and 45 percent of all drugs sales in the United States.

Chino had always, he told me, been puzzled by one thing about his mother. Since she was openly a lesbian, how did she end up becoming pregnant—and by a cop, the species of man she had good reason to loathe the most? He found out the answer when he was thirteen. He explained his confusion to his aunt, Rose, who then offered, coldly, a story. In 1980, Chino’s mother, Deborah, was raped by his father, Victor. Deborah was a black crack addict. Victor was a white NYPD officer, there to arrest her. So Chino is a child of the drug war in the purest sense.

He was conceived on one of its battlefields. Chino had already known the vague outlines of his mother’s life. He constructed a story that strung together his own fragmented memories of her and the hushed conversations he overheard from his relatives. Deborah was abandoned by her biological mother in the hospital as soon as she was born—perhaps because her mother was herself a drug addict.

Long after, Chino will describe this, the night of his conception, with a controlled anger. Cops could rape with impunity “because who’s going to believe a drug addict, right? Who’s going to believe somebody who’s addicted to a substance and will do anything to get that substance, including lie? Who’s going to believe somebody who’s been in and out of prison the majority of their adult life?

Chino was first put into a jumpsuit and caged when he was thirteen. He was sent to Spofford Juvenile Detention Facility in the Bronx as punishment for his violent “street shit” against other teenagers, which he carried out because “the dealing puts me in positions where my default emotion is anger and my default position is retaliation.

Nobody tried to talk to him about why he was there. Their manner wasn’t cold or aggressive: it was utterly indifferent. In this child prison, you could watch TV, watch TV, or watch TV. Oh—or you could play Spades. Chino remembers: “To say I felt alone would be an understatement. I felt like an animal . . . When you go to prison, the one thing you got to check at the door is not your wallet or your jewelry. It’s your humanity.” He was being taught, in stages, that life is a series of shakedowns and shoot-outs, punctuated by boredom.

In prison, “being humane can get you fucking hurt . . . Simple shit like, [if] you’re home in the world and somebody knocks on your door and says, ‘Can I borrow some toothpaste, a cup of sugar?’ you’re like—why not? It’s fucking sugar. Who cares? Take the whole fucking thing . . . You don’t do that shit in jail . . . You can’t do that shit. That just opens up the door for a lot of bullshit . . . People thinking you’re a punk and they can just take from you. It’s called friendly extortion. It’s like . . . ‘I know you want to give me that, right? I know you want to give me a pack of cigarettes.’

As Chino guided me through his world, I kept thinking about the parts of ghetto culture that seem irrational and bizarre to outsiders—the obsession with territory, the constant demand for “respect.” And I began to think maybe they are not so irrational. You have no recourse to the law to protect your most valuable pieces of property—your drug supply—so you have to make damn sure people show you respect and stay out of your territory. The demand for respect, I began to see, is the only way this economy can function. If enough of the local economy is run by these rules, they come to dominate the neighborhood, even the people who manage to stay out of the drug trade.

But the role of the drug war went deeper into Chino’s story than that—to its very start. In the midst of all this violence—gang-on-gang, gang-on-police, police-on-gang, police-on-anyone-in-gang-areas—the rape of an addict like Deborah became something that passed unpunished. It was “not only normalized,” Chino said, “but accepted. And accepted in such an insidious way that it’s almost overlooked . . . There’s no level of humanity that it’s acceptable for these people to be treated” with. Instead, they are viewed “in this very degrading, almost animalistic way . . . It’s not just there’s no sense of justice—[there’s] no sense they need justice. They’re so far down on the human level that justice doesn’t even apply to them. That’s one of the most tremendous impacts in the drug war.

Professor Jeffrey Miron of Harvard University has shown that the murder rate has dramatically increased twice in U.S. history—and both times were during periods when prohibition was dramatically stepped up. The first is from 1920 to 1933, when alcohol was criminalized. The second is from 1970 to 1990, when the prohibition of drugs was dramatically escalated. In both periods, people like Chino responded to the incentives to be terrifying and to kill, in order to control an illegal trade. By the mid-1980s, the Nobel Prize–winning economist and right-wing icon Milton Friedman calculated that it caused an additional 10,000 murders a year in the United States. That’s the equivalent of more than three 9/11s every single year. Professor Miron argues this is an underestimate. Take the drug trade away from criminals, he calculates, and it would reduce the homicide rate in the United States by between 25-75%.

Beyond Chino Hardin, there is another layer of gangsters controlling the neighborhood. Beyond them is a network of smugglers who transported the drugs from the U.S. border to New York. Beyond them is a mule who carried them across the border. Beyond them is a gang controlling the transit through Mexico, or Thailand, or Equatorial Guinea. Beyond them is a gang controlling the production in Colombia, or Afghanistan. Beyond them is a farmer growing the opium or coca. And at every level, there is a war on drugs, a war for drugs, and a culture of terror, all created by prohibition.

I interviewed 16 current or former law enforcement officials, from the Swiss mountains to the U.S.-Mexico borde.

At the beginning of the 21st century, Leigh Maddox was standing on the I-95, the long stretch of highway that leads into Baltimore. She was a police captain with long hair and a short temper. Her men were waging the war on drugs by pulling over cars and hunting through them for contraband. Leigh had been busting people for drug possession like this for years. Her cops had clear orders: Go for numbers. Get the maximum possible arrests. Don’t worry about how severe the offense is. If a person is found with any drugs at all, even the tiniest roach, bust them. She was Anslinger’s dream girl made flesh.

Leigh’s support for the drug war was an act of compassion. She genuinely believed that she was making the world a better place by protecting people from drugs and drug gangs. She is a kind and decent person, and that is what drove her to fight the drug war.

Her officers all knew they could seize the property of anyone they arrested for drug offenses to be auctioned off, with much of the proceeds—usually 80 percent—going straight back into the local police budget. “So if you stop a car [and search it and find], say, four million [dollars in cash]—not unusual—shit, that’s good,” Leigh said.

The prisons were crammed with people serving the harshest possible sentences. The streets were militarized.

Yet all over the United States—all over the world—police officers were noticing something strange. If you arrest a large number of rapists, the amount of rape goes down. If you arrest a large number of violent racists, the number of violent racist attacks goes down. But if you arrest a large number of drug dealers, drug dealing doesn’t go down.

When Levine was told to go to one of the most notorious drug-selling corners in Manhattan—near the top of Ninety-Second Street—and “clean up that damned corner, once and for all,” he was delighted. In a long surveillance operation, his team identified 100 likely street dealers within 50 feet who work from the moment the sun falls to the moment the sun rises. Within two weeks, he had busted around 80% of them. He was satisfied, and for a couple of days, there was less drug activity. But within a week, everything was back to normal, “as if we had never been there,” as Levine puts it in his writing. Why? Because “as every dealer knows, if he is arrested, there are hundreds right behind him ready to take his place.” He asked himself: “If all those cops and agents couldn’t get this one corner clean, what is the purpose of this whole damned drug war?

Back on the roads running into Baltimore, Leigh was discovering something that was going to change her life. It was even worse than Levine suspected. It’s not just that arresting dealers doesn’t cause any reduction in crime. Whenever her force arrested gang members, it appeared to actually cause an increase in violence, especially homicides. At first this puzzled her, but it was a persistent pattern. Why would arresting drug dealers cause a rise in murders? Gradually, she began to see the answer. “So what happens is we take out the guy at the top,” Leigh explains, so “now, nobody’s in charge, and [so the gangs] battle it out to see who’s going to be in charge.

Leigh was beginning to realize that while she went into this job determined to reduce murder, she was in fact increasing it. She wanted to bust the drug gangs, but in fact she was empowering them.

The 1993 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse found that 19 percent of drug dealers were African American, but they made up 64 percent of the arrests for it. Largely as a result of this disparity, there was an outcome that was more startling still. In 1993, in the death throes of apartheid, South Africa imprisoned 853 black men per hundred thousand in the population. The United States imprisons 4,919 black men per hundred thousand (versus only 943 white men).

At any given time, 40 to 50% of black men between the ages of 15 and 35 are in jail, on probation, or have a warrant out for their arrest, overwhelmingly for drug offenses. You have pressure on you from above to get results.

We humans are good at suppressing our epiphanies, especially when our salaries and our friendships depend on it. She knew that a big chunk of her police department’s budget ran on the money they got from seizing drug suspects’ property. What would happen to all their jobs if that were taken away from the cops? She deliberately kept herself so busy that “I just didn’t have any time to think about it.” As she explained this to me, I realized that for Chino and for Leigh, all the incentives laid out by prohibition were to keep on fighting their wars and shooting their guns and ignoring their doubts.

Leigh discovered she was not alone. A friend told her about a group called Law Enforcement Against Prohibition (LEAP), an organization of cops and judges and prison officers fighting to end the drug war so they can bankrupt the drug gangs.

Once you have been busted for a drug offense you are virtually unemployable for the rest of your life. You will never work again. You will be barred from receiving student loans. You will be evicted from public housing. You will be barred from even visiting public housing. “Say your mother lives in public housing, and you get arrested for possession, and you go visit her,” Leigh says. “If the housing authority find out you’ve been there [they will say] you’ve violated the lease and they’ll kick [the whole family] out.” I kept meeting people like this across the United States—second-class citizens, stripped even of the vote, because at some point in the past, they possessed drugs.

Why Anslinger killed Billie Holiday

Jazz was the opposite of everything Harry Anslinger believed in. It is improvised, and relaxed, and free-form. It follows its own rhythm. Worst of all, it is a mongrel music made up of European, Caribbean, and African echoes, all mating on American shores. To Anslinger, this was musical anarchy, and evidence of a recurrence of the primitive impulses that lurk in black people, waiting to emerge.

Harry took jazz as yet more proof that marijuana drives people insane.

Anslinger looked out over a scene filled with men like Charlie Parker, Louis Armstrong, and Thelonious Monk, and—as the journalist Larry Sloman recorded—he longed to see them all behind bars. He wrote to all the agents he had sent to follow them, and instructed: “Please prepare all cases in your jurisdiction involving musicians in violation of the marijuana laws. We will have a great national round-up arrest of all such persons on a single day. I will let you know what day.” His advice on drug raids to his men was always “Shoot first.”

He reassured congressmen that his crackdown would affect not “the good musicians, but the jazz type.” But when Harry came for them, the jazz world would have one weapon that saved them: its absolute solidarity. Anslinger’s men could find almost no one among them who was willing to snitch, and whenever one of them was busted, they all chipped in to bail him out. In the end, the Treasury Department told Anslinger he was wasting his time taking on a community that couldn’t be fractured, so he scaled down his focus until it settled like a laser on a single target—perhaps the greatest female jazz vocalist there ever was.

Billie Holiday was born a few months after the Harrison Act, the first law banning cocaine and heroin, and it would become her lifelong twin. Not long after Billie’s birth, her nineteen-year-old mother, Sadie, became a prostitute, while her seventeen-year-old father vanished. He later died of pneumonia in the South because he couldn’t find a hospital that would treat a black man. Billie brought herself up on the streets of Baltimore, alone, defiant.

The last address she had been given, only to find it was a brothel. Her mother worked there for a pittance and had no way to keep her. Before long, Billie was thrown out, and she was so hungry she could barely breathe without it hurting. There was, Billie came to believe, only one solution. A madam offered her a 50% cut for having sex with strangers. She was 14 years old. Before long, Billie had her own pimp. He was a violent, cursing thug named Louis McKay, who was going to break her ribs and beat her till she bled. He was also—perhaps more crucially—going to meet Harry Anslinger many years later, and work with him.

Billie was caught prostituting by the police, and once again, instead of rescuing her from being pimped and raped, they punished her. She was sent to prison on Welfare Island, and once she got out, she started to seek out the hardest and most head-blasting chemicals she could. At first her favorite was White Lightning, a toxic brew containing 70-proof alcohol, and as she got older, she tried to stun her grief with harder and harder drugs. One night, a white boy from Dallas called Speck showed her how to inject herself with heroin. You just heat up the heroin in a spoon and inject it straight into your veins. When Billie wasn’t drunk or high, she sank into a black rock of depression and could barely speak. She would still wake in the night screaming, remembering her rape and imprisonment. “I got a habit, and I know it’s no good,” she told a friend, “but it’s the one thing that makes me know there’s a person called Billie Holiday. I am Billie Holiday.

One day, starving, she walked a dozen blocks in Harlem, asking in every drinking hole if they had any work for her, and she was rejected everywhere. Finally she walked into a place called the Log Cabin and explained she could work as a dancer, but when she tried a few moves, it was obvious she wasn’t good enough. Desperate, she told the owner maybe she could sing. He pointed her toward an old piano man in the corner and told her to give him a song. As she sang “Trav’llin’ All Alone,” the customers put down their drinks and listened. By the time she finished her next song, “Body and Soul,” there were tears running down their cheeks.

Louis McKay graduated from being her pimp to being her “manager” and husband: he stole almost all her money. After her greatest performance at Carnegie Hall, he greeted her by punching her so hard in the face she was sent flying. Her story was about to crash into Harry Anslinger’s. He had been, it turned out, watching her very carefully.

When Billie sang “Loverman, where can you be?” she wasn’t crying for a man—she was crying for heroin. But when she found out her friends in the jazz world were using the same drug, she begged them to stop. Never imitate me, she cried. Never do this. She kept trying to quit.

Billie was busted again, she was put on trial. She stood before the court looking pale and stunned. “It was called ‘The United States of America versus Billie Holiday,’ ” she said, “and that’s just the way it felt.” She refused to weep on the stand. She told the judge she didn’t want any sympathy. She just wanted to be sent to a hospital so she could kick the drugs and get well. Please, she said to the judge, “I want the cure.” She was sentenced instead to a year in a West Virginia prison, where she was forced to go cold turkey and work during the days in a pigsty, among other places.

Now, as a former convict, she was stripped of her cabaret performer’s license, on the grounds that listening to her might harm the morals of the public. This meant she wasn’t allowed to sing anywhere that alcohol was served—which included all the jazz clubs in the United States.

Billie was finally silenced. She had no money to look after herself or to eat properly. She couldn’t even rent an apartment in her own name.

When she was forced to interact with people, she was becoming more and more paranoid. If Jimmy Fletcher had been one of Them, who else was? She believed—correctly, it turns out—that some of the people around her were informing on her to Anslinger’s army. “You didn’t know who to trust,” her friend Yolande Bavan told me. “So-called friends—were they friends? What were they?” Everywhere she went, there were agents asking about her, demanding details. She began to push away even her few remaining friends, because she was terrified the police would plant drugs on them, too—and that was the last thing she wanted for the people she loved.

When Billie Holiday stood on stage, her hair was pulled back tightly, her face was round and shining in the lights, and her voice was scratched with pain. It was on one of these nights, in 1939, that she started to sing a song that would become iconic: Southern trees bear a strange fruit, Blood on the leaves and blood at the root. Before, black women had—with very few exceptions—been allowed on stage only as beaming caricatures, stripped of all real feeling. But now, here, she was Lady Day, a black woman expressing grief and fury at the mass murder of her brothers in the South—their battered bodies hanging from the trees.

The audience listened, hushed. Many years later, this moment would be called “the beginning of the civil rights movement.” Lady Day was ordered by the authorities to stop singing this song. She refused.

He knew that to secure his bureau’s future, he needed a high-profile victory, over intoxication and over the blacks, and so he turned back to Billie Holiday. To finish her off, he called for his toughest agent—a man who was at no risk of falling in love with her, or anyone else [not excerpted from the book is a great story of an agent sent out to get her who falls in love with her instead]. Here’s a description of the stone-cold killer sent to replace him: The Japanese man couldn’t breathe. Colonel George White—a vastly obese white slab of a man—had his hands tightened around his throat, and he was not letting go. Once it was all over, White told the authorities he strangled this “Jap” because he believed he was a spy. But privately, he told his friends he didn’t really know if his victim was a spy at all, and he didn’t care. “I have a lot of friends who are murderers,” he bragged years later, and “I had very good times in their company.” He boasted to his friends that he kept a photo of the man he had throttled hanging on the wall of his apartment, always watching him. So as he got to work on Billie, Colonel White was watched by his last victim, and this made him happy.

When he came for her on a rainy day at the Mark Twain Hotel in San Francisco without a search warrant, Billie was sitting in white silk pajamas in her room. This was one of the few places she could still perform, and she badly needed the money. She insisted to the police that she had been clean for over a year. White’s men declared they had found opium stashed in a wastepaper basket next to a side room and the kit for shooting heroin in the room, and they charged her with possession. But when the details were looked at later, there seemed to be something odd: a wastepaper basket seems an improbable place to keep a stash, and the kit for shooting heroin was never entered into evidence by the cops—they said they left it at the scene. When journalists asked White about this, he blustered; his reply, they noted, “appeared a little defensive.

Billie insisted the junk had been planted in her room by White, and she immediately offered to go into a clinic to be monitored: she would experience no withdrawal symptoms, she said, and that would prove she was clean and being framed. She checked herself in at a cost of one thousand dollars, and she didn’t so much as shiver.

George White, it turns out, had a long history of planting drugs on women. He was fond of pretending to be an artist and luring women to an apartment in Greenwich Village where he would spike their drinks with LSD to see what would happen. One of his victims was a young actress who happened to live in his building, while another was a pretty blond waitress in a bar. After she failed to show any sexual interest in him, he drugged her to see if that would change. “I toiled whole-heartedly in the vineyards because it was fun, fun, fun,” White boasted. “Where else [but in the Bureau of Narcotics] could a red-blooded American boy lie, kill, cheat, steal, rape and pillage with the sanction and blessing of the All-Highest?

One of the ambulance drivers recognized her, so she ended up in a public ward of New York City’s Metropolitan Hospital. As soon as they took her off oxygen, she lit a cigarette. “Some damn body is always trying to embalm me,” she said, but the doctors came back and explained she had an array of very serious illnesses: she was emaciated because she had not been eating; she had cirrhosis of the liver because of chronic drinking; she had cardiac and respiratory problems due to chronic smoking; and she had several leg ulcers caused by starting to inject street heroin once again. They said she was unlikely to survive for long—but Harry wasn’t done with her yet. “You watch, baby,” Billie warned from her tiny gray hospital room. “They are going to arrest me in this damn bed.” Narcotics agents were sent to her hospital bed and said they had found less than one-eighth of an ounce of heroin in a tinfoil envelope. They claimed it was hanging on a nail on the wall, six feet from the bottom of her bed—a spot Billie was incapable of reaching. They summoned a grand jury to indict her, telling her that unless she disclosed her dealer, they would take her straight to prison. They confiscated her comic books, radio, record player, flowers, chocolates, and magazines, handcuffed her to the bed, and stationed two policemen at the door. They had orders to forbid any visitors from coming in without a written permit, and her friends were told there was no way to see her. Her friend Maely Dufty screamed at them that it was against the law to arrest somebody who was on the critical list. They explained that the problem had been solved: they had taken her off the critical list. So now, on top of the cirrhosis of the liver, Billie went into heroin withdrawal, alone. A doctor was brought into the hospital at the insistence of her friends to prescribe methadone.

She was given it for ten days and began to recover: she put on weight and looked better. But then the methadone was suddenly stopped, and she began to sicken again. When finally a friend was allowed in to see her, Billie told her in a panic: “They’re going to kill me. They’re going to kill me in there. Don’t let them.” The police threw the friend out.

One day, her pimp-husband Louis MacKay turned up at the hospital—after informing on her—and ostentatiously read the Twenty-Third Psalm over her bed. It turned out he wanted her to sign over the rights to her autobiography to him, the last thing she still controlled. She pretended to be unconscious.

On the street outside the hospital, protesters gathered, led by a Harlem pastor named the Reverend Eugene Callender. They held up signs reading “Let Lady Live.” Callender had built a clinic for heroin addicts in his church, and he pleaded for Billie to be allowed to go there to be nursed back to health. His reasoning was simple, he told me in 2013: addicts, he said, “are human beings, just like you and me.” Punishment makes them sicker; compassion can make them well. Harry and his men refused. They fingerprinted Billie on her hospital bed. They took a mug shot of her on her hospital bed. They grilled her on her hospital bed without letting her talk to a lawyer.

4 Responses to The war on drugs. A book review of “Chasing the scream”