[ If you found this post interesting, the following posts are even better (more detailed and in-depth):

- Tilting at Windmills, Spain’s disastrous attempt to replace fossil fuels with Solar PV, Part 1

- Tilting at Windmills, Spain’s disastrous attempt to replace fossil fuels with Solar PV, Part 2. Critiques and rebuttals of “Spain’s Photovoltaic Revolution. The Energy Return on Investment”, by Pedro Prieto and Charles A.S. Hall

Alice Friedemann www.energyskeptic.com author of “When Trucks Stop Running: Energy and the Future of Transportation”, 2015, Springer and “Crunch! Whole Grain Artisan Chips and Crackers”. Podcasts: Practical Prepping, KunstlerCast 253, KunstlerCast278, Peak Prosperity , XX2 report ]

Questions about EROI at researchgate.net 2015-2017

Khalid Abdulla, University of Melbourne asks: Why is quality of life limited by EROI with renewable Energy? There are many articles explaining that the Energy Return on (Energy) Invested (EROI, or EROEI) of the sources of energy which a society uses sets an upper limit on the quality of life (or complexity of a society) which can be enjoyed (for example this one). I understand the arguments made, however I fail to understand why any energy extraction process which has an external EROI greater than 1.0 cannot be “stacked” to enable greater effective EROI. For example if EROI for solar PV is 3.0, surely one can get an effective EROI of 9.0 by feeding all output energy produced from one solar project as the input energy of a second? There is obviously an initial energy investment required, but provided the EROI figure includes all installation and decommissioning energy requirements I don’t understand why this wouldn’t work. Also I realise there are various material constraints which would come into play; but why does this not work from an energy point of view?

Charles A. S. Hall replies: As the person who came up with the term EROI in the 1970s (but not the concept: that belongs to Leslie White, Fred Cotrell, Nicolas Georgescu Roegan and Howard Odum) let me add my two cents to the existing mostly good posts. The problem with the “stacked” idea is that if you do that you do not deliver energy to society with the first (or second or third) investment — it all has to go to the “food chain” with only the final delivering energy to society. So stack two EROI 2:1 technologies and you get 4:2, or the same ratio when you are done.

The second problem is that you do not need just 1.1:1 EROI to operate society. We (Hall, Balogh and Murphy 2009) studied how much oil would need to be extracted to drive a truck including the energy to USE the energy. So we added in the energy to get, refine and deliver the oil (about 10% at each step) and then the energy to build and maintain the roads, bridges, vehicles and so on. We found you needed to extract 3 liters at the well head to use 1 liter in the gas tank to drive the truck, i.e. an EROI of 3:1 was needed.

But even this did not include the energy to put something in the truck (say grow some grain) and also, although we had accounted for the energy for the depreciation of the truck and roads, but not the depreciation of the truck driver, mechanic, street mender, farmer etc.: i.e. to pay for domestic needs, schooling, health care etc. of their replacement. Pretty soon it looked like we needed an EROI of at least 10:1 to take care of the minimum requirements of society, and maybe 15:1 (numbers are very approximate) for a modern civilization. You can see that plus implications in Lambert 2014.

I think this and incipient “peak oil” (Hallock et al.) is behind what is causing most Western economies to slow or stop their energy and economic growth. Low EROI means more expensive oil (etc) and lower net energy means growth is harder as there is less left over after necessary “maintenance metabolism”. This is explored in more depth in Hall and Klitgaard book “Energy and the wealth of Nations” (Springer).

Khalid Abdulla asks: I’m still struggling a little bit with gaining an intuition of why it is not possible to stack/compound EROI. If I understand your response correctly part of the problem is that while society is waiting around for energy from one project to be fed into a second project (etc.) society needs to continue to operate (otherwise it’d all be a bit pointless!) and this has a high energy overhead. I understand that with oil it is possible to achieve higher external EROI by using some of the oil as the main source of energy for extraction/processing. Obviously this means less oil is delivered to the outside world, but it is delivered at a higher EROI which is more useful. I don’t understand why a similar gearing is not possible with renewables. Is it something to do with the timing of the input energy required VS the timing of the energy which the project will deliver over its life?

Charles A. S. Hall replies: Indeed if you update the QUALITY of the energy you can come out “ahead”. My PhD adviser Howard Odum wrote a lot about that, and I am deeply engaged in a discussion about the general meaning of Maximum Power (a related concept) with several others. So you can willingly turn more coal into less electricity because the product is more valuable. Probably pretty soon (if we are not already) we will be using coal to make electricity to pump out ever more difficult oil wells….

I have also been thinking about EROI a lot lately and about what should the boundaries of analysis be. One of my analyses is available in the book “Spain’s PV revolution: EROI and.. available from Springer or Amazon.

To me the issue of boundaries remains critical. I think it is proper to have very wide boundaries. Let’s say we run an economy just on a big PV plant. If the EROI is 8:1 (which you might get, or higher, from examining just the modules) then it seems like you could make your society work. But let’s look closer. If you add in security systems, roads, and financial services and the EROI drops to 3:1 then it seems more problematic. But if you add in labor (i.e. the energy it takes to make the food, housing etc that labor buys with its salaries, calculated from national mean energy intensities times salaries for all necessary workers) it might drop to 1:1. Now what this means is that the energy from the PV system will support all the purchases of the workers that are building/maintaining the PV system, let’s say 10% will be taken care of, BUT THERE WILL BE NO PRODUCTION OF GOODS AND SERVICES for the rest of the population. To me this is why we should include salaries of the entire energy delivery system (although I do not because it remains so controversial). I think this concept, and the flat oil production in most of the world, is why we need to think about ALL the resources necessary to deliver energy from a project/ technology/nation.”

Khalid Abdulla: My main interest is whether the relatively low EROI of renewable energy sources fundamentally limits the complexity of a society that can be fueled by them.

Charles A. S. Hall replies: Perhaps the easiest way to think about this is historical: certainly we had lots of sunshine and clever minds in the past. But we did not have a society with many affluent people until the industrial revolution, based on millions of years of accumulated net energy from sunshine. An affluent king, living a life of affluence less than most people in industrial societies now, was supported by the labor of thousands or millions of serfs harvesting solar energy. The way to get rich was to exploit the stored solar energy of other societies through war (see Plutarch or Tainter’s the collapse of complex societies).

But most renewable energy (good hydropower is an exception) are low EROI or else seriously constrained by intermittency. Look at all the stuff required to support “free” solar energy. We (and Palmer and Weisbach independently) found EROIs of about 3:1 at best when all costs are accounted for.

The lower the EROI the larger the investment needed for the next generation: that is why fossil fuels with EROIs of 30 or 50 to one have led to such wealth: the other 29 or 49 have been deliverable to society to do economic work or that can be invested in getting more fossil fuels. If the EROI is 2:1 obviously half has to go into the next generation for the growth and much less is delivered to society. One can speculate or fantasize about what one can do with some future technology but having been in the energy business for 50 years I have seen many come and go. Meanwhile we still get about 75-80% of our energy from fossil fuels (with their attendant high EROI).

Obviously we could have some kind of culture with labor intensive, low energy input systems if people were willing to take a large drop in their life style. I fear the problem might be that people would rather go to war than accept a decline in life style.

Lee’s assessment of the traditional !Kung hunter gatherer life style implies an EROI of 10:1 and lots of leisure (except during droughts–which is the bottleneck). Past agricultural societies obviously had a positive EROI based on human labor input — otherwise they would have gone extinct. But it required something like a hectare per person. According to Jared Diamond cultures became more complex with agriculture vs hunter gatherer.

The best assessment I have about EROI and quality of life possible is in: Lambert, Jessica, Charles A.S. Hall, Stephen Balogh, Ajay Gupta, Michelle Arnold 2014 Energy, EROI and quality of life. Energy Policy Volume 64:153-167 http://authors.elsevier.com/sd/article/S0301421513006447 — It is open access. Also our book: Hall and Klitgaard, Energy and the wealth of nations. Springer

At the moment the EROI of contemporary agriculture is 2:1 at the farm gate but much less, perhaps one returned for 5 invested by the time the food is processed, distributed and prepared (Hamilton 2013).

As you can see from these studies to get numbers with any kind of reliability requires a great deal of work.

Sourabh Jain asks: Would it be possible to meet the EROI goal of, say for example 10:1, in order to maintain our current life style by mixing wind, solar and hydro? Can we have an energy system various renewable energy sources of different EROI to give a net EROI of 10:1?

Charles A. S. Hall replies: Good question. First of all I am not sure that we can maintain our current life style on an EROI of 10:1, but let’s assume we can (Hall 2014, Lambert 2014). We would need liquid fuels of course for tractors , airplanes and ships — I cannot quite envision running those machines on electricity.

The problem with wind is that it tends to blow only 30% of the time, so we would need massive storage. To the degree that we can meet intermittency with hydro that is good, although it is tough on the fish and insects below the dam. The energy cost of that would be huge, prohibitive with respect to batteries, huge with respect to pumped storage, and what happens when the wind does not blow for two weeks, as is often the case?

Solar PV may or may not have an EROI of 10:1 (I assume you know of the three studies that came up with about 3:1: Prieto and Hall, Graham Palmer, Weisbach — but there are others higher and certainly the price and hence presumed energy cost is coming down –but you should also know that many structures are lasting only 12, not 25 years) — — this needs to be sorted out ). But again the storage issue will be important. (Palmer’s rooftop study included storage).

These are all important issues. So I would say the answer seems to be no, although it might work well for let’s say half of our energy use. As time goes on that percentage might increase (or decrease).

Jethro Betcke writes: Charles Hall: You make some statements that are somewhat inaccurate and could easily mislead the less well informed: Wind turbines produce electricity during 70 to 90% of the time. You seems to have confused capacity factor with relative time of operation. Using a single number for the capacity factor is also not so accurate. Depending on the location and design choices the capacity factor can vary from 20% to over 50%. With the lifetime of PV systems you seem to have confused the inverter with the system as a whole. The practice has shown that PV modules last much longer thatn the 25 years guaranteed by the manufacturer. In Oldenburg we have a system from 1976 that is still producing electricity and shows little degradation loss [1]. Inverters are the weak point of the system and sometimes need to be replaced. Of course, this would need to be considered in an EROEI calculation. But this is something different than what you state. [1] http://www.presse.uni-oldenburg.de/download/einblicke/54/parisi-heinemann-juergens-knecht.pdf

Charles A. S. Hall replies: I resent your statement that I am misleading anyone. I write as clearly, accurately and honestly as I can, almost entirely in peer reviewed publications, and always have. I include sensitivity analysis while acknowledging legitimate uncertainty (for example p. 115 in Prieto and Hall). Some people do not like my conclusions. But no one has shown with explicit analysis that Prieto and Hall is in any important way incorrect. At least three other peer reviewed papers) (Palmer 2013, 2014; Weisbach et al. 2012 and Ferroni and Hopkirk (2016) have come up with similar conclusions on solar PV. I am working on the legitimate differences in technique with legitimate and credible solar analysts with whom I have some differences , e.g. Marco Raugei. All of this will be detailed in a new book from Springer in January on EROI.

First I would like to say that the bountiful energy blog post is embarrassingly poor science and totally unacceptable. As one point the author does not back his (often erroneous) statements with references. The importance of peer review is obvious from this non peer-reviewed post.

Second I do not understand your statement about wind energy producing electricity 70-90 percent of the time. In England, for example, it is less than 30 percent (Jefferson 2015).

Third your statement on the operational lifetime of actual operational PV systems is incorrect. Of course one can find PV systems still generating electricity after 30 years. But actual operational systems requiring serious maintenance (and for which we do not yet have enough data) often do not last more than 18-20 years, For example Spain’s “Flagship ” PV plant (which was especially well maintained) is having all modules replaced and treated as “electronic trash” after 20 years : http://renewables.seenews.com/news/spains-ingeteam-replaces-modules-at-europes-oldest-pv-plant-538875 Ferroni and Hopkirk found an 18 year lifespan in Switzerland.

Pedro Prieto replies: The production of electricity of wind turbines the 70-90% of time is a very inaccurate quote. Every wind turbine has a nominal capacity in MW. The important factor is not how many hours they move the blades at any working regime, but how many EQUIVALENT peak hours they work at the end of the year. That is, to know how much real energy they generate within one year. This is what the industry uses as a general and accurate measurement and it is the load factor or capacity factor.

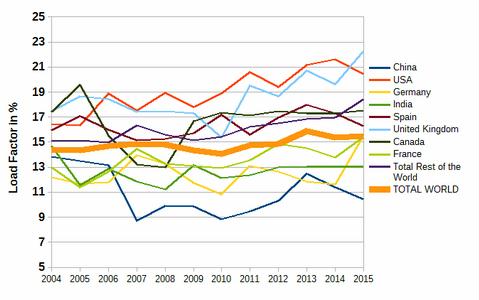

Of course, this factor may change from the location or the design choices, but there is an incontrovertible figure: when we take the total world installed wind power in MW (435 Gw as of 2015) from January 2004 up to December 2015 and the total energy generated in Twh (841 Twh as of 2015) in the same period and calculate the averaged capacity factor, the resulting figure slightly varies around 15% AT WORLD LEVEL. This is REAL LIFE, much more than your unsupported theoretical figures of 20 to over 50% capacity factor in privileged wind fields for privileged wind turbines.

Interesting enough, some countries like the US, United Kingdom or Spain have capacity factors reaching 20% in the last years, but the world total installed capacity has not really improved so much in the last ten years, despite of theoretically much efficient wind turbines (i.e. multipole with permanent magnets), very likely for the reasons that good wind fields in some countries were already used up. Other countries like China, India or France show, on the contrary very poor capacity factors even in 2015.

With respect to the lifetime of the PV systems, nor Charles Hall neither myself have confused the inverter lifetime with the solar PV system as a whole. The practice has not shown that modules have lasted more than 25 years in general over the world installed base. The fact that one single system is still working after more than 30 years of operation, if it was carefully manufactured with high quality materials, and was well cared, cleaned and free from environmental pollutants, like several modules we have also in Spain, does not mean AT ALL that the massive deployments (about 250 GW as of 2015) are going to last over 25 years.

I have to clarify also a common mistake: almost all main world manufacturers guarantee a maximum of 25 years (NOT 30) to the modules, but this is the “power” guarantee. This means that they “guarantee” (assuming they will be still alive as companies in 25 years from the sales period, something which is rather difficult for many of the manufacturers that went out of business in shorter periods of time than the guarantee of their modules. Of course, this guarantee is given with the subsequent module degradation specs over time, which in many cases has been proved be higher than specified.

But not only that. Most of the module manufacturers have a second guarantee: the “material’s guarantee”. And this is offered for between 5 and 10 years. This is the one by which the manufacturer guarantees the module replacement if it fails. Beyond that date, if the module fails, the buyer has to buy a new one (if still being manufactured, with the same specs power and size), because the second guarantee SUPERSEDES the first one.

Last but not least, there is already quite a large experience in Europe (Germany, France, Switzerland, Spain, Italy, etc.) of the number of faulty modules that have been decommissioned in the last years (i.e. period 2010-2015) as for instance, accounted by PV-Cycle, a company specialized in decommission and recycling modules in Europe. As the installed base is well known in volumes per year, it is relatively easy to calculate, in a very conservative (optimistic) mode the percentage over the total that failed and the number of years that lasted in this period and the average years for that sample that died before the theoretical 25-30 years lifetime and make the proportion on the total installed base.

The study conducted by Ferroni and Hopkirk gives an approximate lifetime for the installed base of lower than 20 years. And this is Europe, where the maintenance is supposed to be much better made than in the rest of the developing world. And the figures of failed modules given by PV-Cycle did not include the many potential plants that did not deliver their failed modules to this company for recycling

What it seems impossible for some academic people is to recognize that perhaps the “standards” they adhered to (namely IEA PVPS Task 12 in this case) and through which they published a big number of papers, should be revisited, because they lacked some essential measurements that could help to understand why renewables are not replacing fossils at the required speed, despite having claimed for years that they reached grid parity or that their Levelized Cost of Electricity (LCOE) is cheaper than coal, nuclear or gas.

I am afraid that peer reviewed authors are not immune to having preconceived ideas even more difficult to eradicate. Excessive pride, lack of humility, considerable distance between the academy (i.e. imagined solar production levels versus real data from actual solar PV plants and lack of a systemic vision due to an excess of specialization are the main hurdles. Of course in my humble opinion.

References

- Hall, C.A.S., Balogh, S., Murphy, D.J.R. 2009. What is the Minimum EROI that a Sustainable Society Must Have? Energies, 2: 25-47.

- Hall, Charles A.S., Jessica G.Lambert, Stephen B. Balogh. 2014. EROI of different fuels and the implications for society Energy Policy Energy Policy. Energy Policy, Vol 64 141-52

- Hallock Jr., John L., Wei Wu, Charles A.S. Hall, Michael Jefferson. 2014. Forecasting the limits to the availability and diversity of global conventional oil supply: Validation. Energy 64: 130-153. (here)

- Hamilton A , Balogh SB, Maxwell A, Hall CAS. 2013. Efficiency of edible agriculture in Canada and the U.S. over the past 3 and 4 decades. Energies 6:1764-1793.

- Lambert, Jessica, Charles A.S. Hall, et al. Energy, EROI and quality of life. Energy Policy

3 Responses to EROI explained and defended by Charles Hall, Pedro Prieto, and others