[So much of this was calculus calculating odds that very little of this document was extracted.

Alice Friedemann www.energyskeptic.com author of “When Trucks Stop Running: Energy and the Future of Transportation”, 2015, Springer and “Crunch! Whole Grain Artisan Chips and Crackers”. Podcasts: KunstlerCast 253, KunstlerCast278, Peak Prosperity]

NRC. 2008. Department of Homeland Security Bioterrorism Risk Assessment: A Call for Change .Committee on Methodological Improvements to the Department of Homeland Security’s Biological Agent Risk Analysis. National Research Council.

Extracts from this 173 page document:

The threat posed by biological agents employed in a terrorist attack on the United States is arguably the most important homeland security challenge of our era. Whether natural pathogens are cultured or new variants are bioengineered, the consequence of a terrorist-induced pandemic could be millions of casualties—far more than we would expect from nuclear terrorism, chemical attacks, or conventional attacks on the infrastructure of the United States such as the attacks of September 11, 2001. Even if there were fewer casualties, additional second-order consequences (including psychological, social, and economic effects) would dramatically compound the effects. Bioengineering is no longer the exclusive purview of state sponsors of terrorism; this technology is now available to small terrorist groups and even to deranged individuals.

Today the nation is a long way from being able to meet the challenges posed by a bioterrorist attack. The United States currently has little ability to prevent or detect a biological attack, and the nation’s response systems are unproven. Biological weapons are easily concealed and hard to track. Biological attacks are potentially repeatable, and attribution is extremely difficult,

Advances in biotechnology will augment not only defensive measures but also offensive biological warfare (BW) agent development and allow the creation of advanced biological agents designed to target specific systems—human, animal, or crop” (National Intelligence Council, 2004, p. 36). The report states further that “as biotechnology advances become more ubiquitous, stopping the progress of offensive BW programs will become increasingly difficult” (p. 36).

Serious threats “may consist instead of unannounced attacks by subnational groups using genetically engineered pathogens against American cities” (U.S. Commission on National Security in the 21st Century, 1999, p. 2). Improving the U.S. capability to prevent, detect, and respond to the use of biological weapons is clearly a matter of national urgency. According to recent congressional testimony by the Director of National Intelligence, al-Qaeda and other terrorist groups continue to show interest in these weapons (Negroponte, 2007).

The biotechnology revolution will make even more potent and sophisticated weapons available to small or relatively unsophisticated groups.

One scenario, involving an aerosol anthrax attack in a highly populated U.S. city, begins with a single aerosol anthrax attack delivered by a truck using a concealed improvised spraying device in one densely populated urban city with a significant commuter workforce. Anthrax spores, delivered by aerosol, result in inhalation anthrax, which develops when the spores are inhaled into the lungs and germinate into vegetative bacteria capable of causing disease. A progressive infection follows. Attacks are made in five separate metropolitan areas in a sequential manner. Three cities are attacked initially, followed by two additional cities 2 weeks later. The crisis stresses and breaks the response capabilities of all relevant public and private institutions, rapidly leading to 328,400 exposures; 13,200 fatalities; and 13,300 other casualties. The full political, psychological, social, and economic impacts of the attack adversely affect national financial markets and consumer confidence, devastate the local and regional economy, and cause public faith in government to plummet across the country.

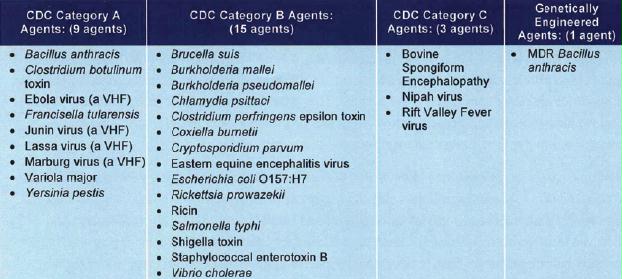

FIGURE 3.1 Biological threat agents as categorized by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). SOURCE: Available at www.bt.cdc.gov/Agent/Agentlist.asp

FIGURE 3.1 Biological threat agents as categorized by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). SOURCE: Available at www.bt.cdc.gov/Agent/Agentlist.asp

- High-priority, Category A agents include organisms that pose a risk to national security because they can be easily disseminated or transmitted from person to person, they result in high mortality rates and have the potential for major public health impacts, they might cause social disruption, and they require special action for public health preparedness.

- Category B, the second-highest priority, includes agents that are moderately easy to disseminate, that result in moderate morbidity rates and low mortality rates, and that require specific enhancements of CDC’s diagnostic capacity and enhanced disease surveillance.

- Category C agents include emerging pathogens that could be engineered for mass dissemination in the future because of availability, ease of production and dissemination, and potential for high morbidity and mortality rates and for major health impact. A later CDC-categorized list (CDC, 2007) features the same categories, but with agent entries revised…

Agricultural consequences also need to be considered. Economic activity of U.S. agriculture has been estimated to exceed $1 trillion annually, with exports valued in excess of $50 billion. Protecting U.S. agriculture is critical to the global economy and to the ensuring of an adequate and safe food supply in the United States and other countries. Several assessments of agricultural consequences have shown that livestock and poultry populations are vulnerable to biologic attack. The U.S. Department of Agriculture has identified viruses and bacteria capable of causing wide-scale morbidity and mortality of livestock and poultry that would result in a cessation of international trade and exports costing the United States billions of dollars.