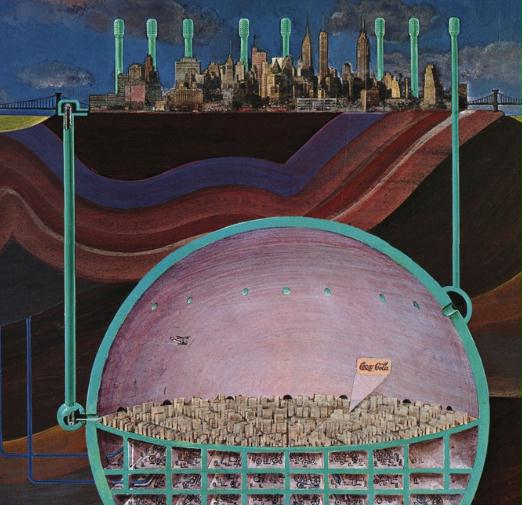

This is city planner Oscar Newman’s probably tongue-in-cheek vision of an enormous spherical underground replica of Manhattan located thousands of feet below the city itself, to be switched into action in the event of a nuclear event. Source: www.6sqft.com

Graff, G.M. 2018. Raven Rock. The Story of the U.S. Governments Secret Plan to Save Itself–While the Rest of Us Die.

At the outset of the cold war, scientists proposed that nationalism had to go away to prevent nuclear wars, which could only be done by having the entire world come under one government that owned all weaponry. That idea was agreed to be impractical.

So the next Big Idea was to go underground and bury urban populations inside mountains linked by subterranean railroads. Life magazine gave this a positive spin “Consider the ant, whose social problems much resemble man. Constructing beautiful urban palaces and galleries, many ants have long lived underground in entire satisfaction.” The military jumped on this underground bandwagon by saying “After all, sunlight isn’t so wonderful. You have to be near a window to benefit by it. With fluorescent fixtures, you get an even light all over the place.”

Edward Teller, father of the H-bomb, tried to convince the Kennedy White House that American life should be moved underground, especially public buildings like schools, libraries, and museums should since they could help save lives and preserve “some of the chief reasons for living.”

If not underground, then cities needed to be much smaller and dispersed in ribbons of narrow, low density, and splitting them up would cost less than going to war. MIT professors proposed encircling urban centers with “life belts” of large paved beltways to speed evacuations. The land around the “life belt” roads would be reserved as parks ready to host large tent cities which erected after a nuclear ar to shelter refugees.

Real estate agents took advantage of bomb fears using titles such as “Small Farms—Out Beyond Range of Atomic Bombs.

Cities made their own attempts to cope:

- New York City distributed two million dog tags to schoolchildren to help officials both identify bodies and reunite separated families after an attack.

- Chicago’s recommended parents tattoo children’s blood type under their armpit—but not on the arm itself in case it was blown off—which would help speed blood transfusions to avoid radiation poisoning. The city also mapped which students lived close enough to school to make it home versus who should remain at school to experience nuclear war with their teachers.

- Jacksonville, Florida distributed the best escape routes for those seeking to flee into Georgia.

At the state level, Kansas, officials calculated they could assemble two million pounds of food that might last two months. In addition citizens could consume wildlife, officials estimated that there were 11 million “man-days” of rabbits, 10 million “man-days” of wild birds, five million “man-days” of edible fish, and nearly 20 million “man-days” of meat in residential pets. The state also planned to confiscate household vitamins for the good of everyone and ration the state’s 28 day supply of coffee.

To help cities, the federal government:

- advised cities to create mortuary zones to ID the bodies and intern them, using Post Office mail trucks to carry casualties

- trained hundreds of police officers across the country on “Emergency Traffic Control,” to aid urban evacuations, and built special civil defense rescue trucks, and planned in 1958 to distribute radiology monitoring kits to all 15,000 American high schools, so that science classes could begin to teach students how to monitor fallout levels after an attack.

The federal government also made “survival crackers” with 3 million bushels of wheat, enough for Nabisco and other companies to make 150 million pounds of crackers. “This is one of the oldest and most proven forms of food known to man,” explained Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense Paul Visher. “It has been the subsistence ration for many portions of the earth for thousands of years. Its shelf life has been established by being edible after 3,000 years in an Egyptian pyramid.” The specially made bulgur crackers were indeed nearly unchanging: A 50-page USDA report on the crackers and their chemistry found merely a “discernible but inconsequential decrease” in flavor after 52months of storage, though the highest compliment ever paid was that they tasted like cardboard. (So for your next natural disaster or Apocalypse, you might want to try making my crackers instead in my book “Crunch! Whole grain artisan chips and crackers”.

The government encouraged people to build their own shelters, and provided free plans for how to construct them, plus examples of shelters were shown at conventions, state fairs, and local fairs. But the truth is these shelters would do no good. Cities would be leveled after a hydrogen bomb was dropped and the only shelters that would survive would need to be hundreds or thousands of feet underground.

The government encouraged homes to have a week of food, and much like Costco sells prepper food today, decades ago Sears, Roebuck & Co. exhibited “Grandma’s Pantry” in 500 of its stores, while women’s magazines had articles titled “Take these steps now to save your family”.

Many Americans remained stubbornly disinterested in nuclear war preparation because they didn’t like to be reminded regularly of how tenuous their daily existence was in the age of nuclear weapons. It was simply difficult to keep up the fear, hard to keep up the psychological pressure that the world might end at any moment.

But plenty of patriotic Americans were paying attention. One program at its peak in 1956 had 380,000 volunteers on the lookout for Russian planes at 17,000 posts, many staffed around the clock.

In the late 1950s the federal government had over 3.2 million square feet of stockpiled burn dressings, paper blankets, 307,000 litters, and 1,400 gas masks, most of these facilities ten to 50 miles from a major target.

For a brief time, there was a shelter craze. IBM promised their 60,000 employees loans to build their shelters and sell construction materials at cost. Jails gave inmates one day off for every day they lived in an underground shelter, and one experiment found 7,000 volunteers to live an average of three days each in a shelter.

But then the public sobered up and realized that only a few people had shelters, and a debate about the morality of the have shelters versus the have no shelters arose.

Those with shelters, such as Charles Davis in Austin, Texas said he was prepared to defend his shelter from the inside and recapture it if others got there first. Pointing to his cache of five guns and a four-inch-thick door, he said, “This isn’t to keep radiation out, it’s to keep people out.”

The very few homeowners nationwide who had taken the advice to build a shelter found themselves quite popular among friends and neighbors: One Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, shelter owner reported receiving half-joking offers of up to $16,000 from neighbors eager to share his shelter. In the back of everyone’s mind, though, was the “Gun Thy Neighbor” debate from the year before. If people were willing to pay money to reserve a spot in a neighbor’s shelter, what panic would possess them in a real attack?

Upping the game, in 1961 Las Vegas’s civil defense leader, J. Carlton Adair, suggested forming a 5,000-man local militia who could help repel by force California refugees who would likely pour across the border after a nuclear attack “like a swarm of locusts. Along the same lines, Beaumont California, between Los Angeles and Phoenix, encouraged households to pack pistols in their nuclear survival kits to fend off the 150,000 Los Angeles refugees passing through Riverside County as they fled.

These morality debates made many Americans realize that they’d be on their own in an attack. The government had no plans for sheltering the entire country. One civil defense official said defensively, “I do not think it is the government’s responsibility to take care of you from the minute you’re born until you die.”

Not that anyone would get enough warning of an attack to get into their shelter or evacuate. The warning sirens were ineffective in the Kenney years, and attempts to remedy that with $10 buzzers in a multi-million dollar program didn’t work out since the buzzer couldn’t provide specific detail or information to homeowners about the attack timing, duration, or scale—or instructions on what to do afterward. The next attempt was another $10 device to be installed in TV sets that was terminated after the Watergate scandal, because the public had lost trust in the government and the public wasn’t about to put something in their TV’s that was controlled by the government.

One of the last plans considered before the government abandoned trying to save the public where evacuation plans. For example the one for New York city included moving the 4.8 million who were carless via subway, train, ferry, barge, cruise ships, aircraft, and buses. In Washington DC several routes were developed for different sections of the city to host areas where hundreds of thousands of refugees would descend on remote country towns where there weren’t shelters or food available. But it didn’t take long to see these plans couldn’t possibly work, so they were abandoned.

If there’s no plan to help the public survive the two weeks shelter is needed from radiation, then there’s certainly no plan for peak oil and other energy and resource crises – unless it’s to stop mass migrations, which would probably happen at the state or local, not federal level.

After our house burned down, I was quite interested in emergency planning, and managed to talk to one of the executives in the state of California. I asked if they had food, tents, and other emergency supplies stockpiled. No she told me, that would open a political can of worms and open the state to criticism they weren’t distributing their stockpile fairly.

Homeland Security and FEMA aren’t preparing our nation for the Permanent Emergency – and how could they and why would they if they abandoned plans to save the public for just 2 weeks (after that it was believed to be safe to emerge). You’re on your own folks!

Raven Rock parts 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6.

Alice Friedemann www.energyskeptic.com author of “When Trucks Stop Running: Energy and the Future of Transportation”, 2015, Springer and “Crunch! Whole Grain Artisan Chips and Crackers”. Podcasts: Derrick Jensen, Practical Prepping, KunstlerCast 253, KunstlerCast278, Peak Prosperity , XX2 report ]