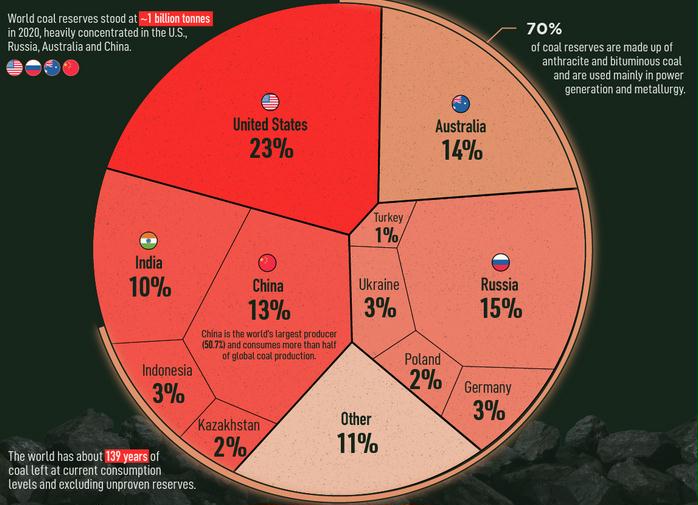

Source: Visual Capitalist (2021) Which countries have the world’s largest coal reserves? The USA has 23% of reserves? I doubt it, the USGS found that nearly half of US coal, in the powder river basin has 35 years left, not 250 years Luppens, James A., et al. 2015. Coal Geology and Assessment of Coal Resources and Reserves in the Powder River Basin, Wyoming and Montana. USGS.

Preface. Below are excerpts from 2 articles. You may want to read Tverberg’s article here since I left out the charts and included just a few excerpts. Some key points:

- The world needs growing energy supply to support the world economy. China is increasingly having difficulty with its energy supply. When China has trouble with its energy supplies, the world as a whole has a problem with its growth in energy supplies.

- China’s shrinking coal and gas reserves will lead to shrinking energy consumption per capita, and that will be extraordinarily traumatic. Population may fall, commodity prices drop to low levels. Debt would tend to default; prices of shares of stock would fall. Many governments would fail. If shrinking energy consumption per capita starts in one country (whether China or elsewhere), it could easily spread to other countries around the world.

Coal especially depends on diesel fuel to be transported by rail or ship since it can’t flow through cheap pipelines like oil or natural gas. When I wrote “When Trucks Stop Running”, 40% of the cargo hauled by rail was coal!!!

Tad Patzek, former chairman of the Department of Petroleum and Geosystems Engineering at the University of Texas, Austin, found that energy-contentwise, global coal peak may have occurred already in 2011. By 2050, remaining coal will provide only half as much energy as today, and carbon emissions from coal will decline 50 % by 2050. Patzek used the same Hubbert methods that successfully predicted peak oil to come to this conclusion (Patzek et al. 2010).

A good percent of remaining coal reserves are lignite with an EROI so low it’s often not worth mining. Consider the knock-on effects of low quality coal and coal shortages on manufacturing, and supply chains in China:

China could face further power shortages this summer despite taking drastic measures to boost coal production, as much of the new supply is of lower quality than before and burns more quickly in power stations. Some utilities in southern China saw coal use rise by nearly 15% in late May from a year ago, but power generation volume remained nearly the same. Increased coal imports by European buyers keen to replace Russian coal and gas supplies have also reduced high-grade coal supplies and pushed international coal prices well above domestic Chinese prices, making imports economically unfeasible for many Chinese power firms. Higher than usual temperatures forecast in eastern and central China this summer may also push up demand for air conditioning, while expected flooding may disrupt power generation from hydropower during the upcoming rainy season (Xu 2022).

And this in turn is halting the production at numerous factories, including those supplying Apple and Tesla. Aluminum production has gone down 7%, cement production 29%, and it’s likely that steel, paper, chemicals, dyes, furniture, soymeal, and glass will production will also be affected (Singh 2021)

Clearly other coal reserves need to be re-evaluated again too. It’s a good bet the reserves in Illinois will go down, since even though coal production is half of what it was 20 years ago, it’s still credited with reserves nearly the size of Montana.

Alice Friedemann www.energyskeptic.com Author of Life After Fossil Fuels: A Reality Check on Alternative Energy; When Trucks Stop Running: Energy and the Future of Transportation”, Barriers to Making Algal Biofuels, & “Crunch! Whole Grain Artisan Chips and Crackers”. Women in ecology Podcasts: WGBH, Jore, Planet: Critical, Crazy Town, Collapse Chronicles, Derrick Jensen, Practical Prepping, Kunstler 253 &278, Peak Prosperity, Index of best energyskeptic posts

***

Tverberg, G. 2019. Seven reasons we should not depend on imported goods from China. ourfiniteworld.com

China consumes more fuel for industrial production than the US, India, Russia, and Japan combined. Because so much production has been outsourced to China, we depend on China for a huge percent of the stuff we use.

China’s coal production peaked in 2013, and oil in 2015. In 2018, China imported 71% of its petroleum (either as crude or as products), and 43% of its natural gas. It was the largest importer in the world with respect to both of these fuels.

For many commodities, China consumes over half of the world’s commodity supply. If China’s industrial demand is growing, prices will tend to rise, allowing more of the mineral to be extracted. Higher commodity prices tend to be needed over time because the ores of highest concentration (and otherwise easiest to extract ores) tend to be extracted first. Ores extracted later tend to be more expensive to extract, so higher prices are required for extraction to be profitable.

China is experiencing peak coal. The consequences are that coal prices cannot rise very high is because if they do, the prices of finished goods will need to rise as well. Wages of workers around the world will not rise at the same time because the higher cost of production takes place due to something that is equivalent to “growing inefficiency.” The coal mined is of lower quality, or in thinner seams, or needs to be transported further. This means that more workers and more fuel is needed for each ton of coal extracted. This leaves fewer workers and less fuel for other industrial tasks, so that, in total, the economy can manufacture fewer goods and services. Because of these issues, countries experiencing peak coal are pushed toward economic contraction.

So peak coal, rather than leading to high prices (to compensate for the higher extraction costs), tends to lead to war, or to tariff fights.

If higher coal prices really were possible over the long term, it would make it possible to open new mines in more distant locations. The location of coal mines is important because transport costs by rail or truck tend to be high.

Based on China’s consumption of diesel and gasoline, it appears that China’s industrial growth suddenly leveled off in 2012 (diesel consumption), while gasoline has risen as China grows their economy more as one of service than industry.

Wang, J.L, et al. 2017. A review of physical supply and EROI of fossil fuels in China. Petroleum Science.

This paper reviews China’s future fossil fuel supply from the perspectives of physical output and net energy output, also known as energy returned on invested (EROI). For society, net energy – the energy available to society after subtracting the energy needed to produce the energy–is the only true energy.

Net energy analyses show that both coal and oil and gas production show a steady declining trend of EROI (energy return on investment) due to the depletion of shallow-buried coal resources and conventional oil and gas resources, which is generally consistent with the approaching peaks of physical production of fossil fuels.

Peak dates in the literature very considerably due to different assumptions about ultimately recoverable resources (URR), what kind of model was used, and differences in the historic production data. For example, peak oil production has been predicted to occur from 2002 to 2037 with peak production rates from 140 Mt/year to 236 Mt/year. So this paper rejects both the very high and very low forecasts, papers that didn’t consider economic factors, and then uses the average result of the remaining studies to come up with these recommended results:

- 2014: Oil production (conventional) peak of 170 Mt/year.

- 2021: Oil production (unconventional) peak 65 Mt/year (based on very few papers)

- 2018: Oil production (conventional and unconventional) peak 230 Mt/year. 9.6 EJ/year)

- 2040: IEA peak demand 780 Mt/year

Similarly, conventional natural gas production peak estimates range from 2018 to 2049 and peak production from 100 to 400 billion cubic meters (bcm)/year. Recommended results:

- 2030: Natural gas production (conventional) peak of 190 Bcm/year

- 2058: Natural gas production (unconventional) peak of 270 Bcm/year.

- 2040: Natural gas peak. 350 Bcm/year. 13.6 EJ/year

- 2040: IEA demand 600 Bcm/year

Coal production peak estimates range from 2010 to 2039 at production rates from 2314 to 6096 Mt/year. In China in 2014, coal provided 73% of total energy supply and 66% of total energy consumption.

- 2020: Coal peak. 4400 Mt/year. 91.9 EJ/year)

China has had an average annual GDP growth rate of 9.8% from 1978 to 2014 due to an increase in annual energy consumption from 570 million tonnes of coal equivalent per year (Mtce/year) to 4260 Mtce/year, at an average annual growth rate of 5.8% (NBSC 2015), with fossil fuels accounting for 90% of energy consumption.

It’s likely that the role of natural gas will increase, coal will decrease, and oil remain the same share of fossils consumed. China has been a net oil importer since 1993.

[ My comment: That is, as long as imports are available. Oil producing nation populations and petrochemical industries have been growing for decades. If China increases their oil imports, this will affect all other nations, since after oil production nations peak, exports are expected to decline rapidly, i.e. the Export Land Model ].

Net energy or energy (energy output minus energy input to get that energy)

In the past, fossil fuel resources with high quality (which means very little energy inputs required to extract these resources) were abundant, and their EROI values were usually greater than 30, and up to 100 and over. So there was no great need in the past to be concerned with the fossil fuel net energy outputs or EROIs. However, we have now become aware that the EROI, and hence the amount of energy surplus of fossil fuels to society, has changed recently, due to the rapid depletion of high-quality fossil fuels after 2000 (Wang et al. 2017).

The EROI of China’s overall oil and gas is much lower than that of coal and was forecast to be 9.9 in 2012. Unfortunately, there are no separate studies for the individual oil and gas industries at a national level because oil and gas are usually concomitant and their input data are also mixed. If the input data for oil and gas can be collected separately, it can be expected that the EROI of oil will be lower than gas since China’s oil industry has been developed for years and has entered its mid- and late period, while gas industry is still in its middle and early period.

The energy inputs during the mid- and later period are much larger. For example, the Daqing oil field, the largest oil field in China, has been developed for nearly 60 years and entered its late period. To maintain its production level or reduce its production decline rate, the Daqing oil field has been using advanced enhanced oil recovery (EOR) methods for many years, such as polymer flooding and the alkaline-surfactant-polymer (ASP) flooding method. These methods are well known for their high cost and environmental impact, which in turn leads to lower EROI and declines in the Daqing oil field’s EROI, which is down to 6.4 in 2012.

References

Patzek, T., et al. 2010. A global coal production forecast with multi-Hubbert cycle analysis.

Energy 35: 3109–3122

Singh S (2021) China power crunch spreads, shutting factories and dimming growth outlook. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/china/chinas-power-crunch-begins-weigh-economic-outlook-2021-09-27/

Xu M (2022) Analysis: Quantity over quality – China faces power supply risk despite coal output surge. Reuters

https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/quantity-over-quality-china-faces-power-supply-risk-despite-coal-output-surge-2022-06-21/