Preface. This National Research Council 465-page report may be the most comprehensive study of the U.S. prison system there is. It will make you cry. I’ve excerpted about one-sixth of it below. It is shocking that the “U.S. penal population of 2.2 million adults is the largest in the world. In 2012, close to 25% of the world’s prisoners were held in American prisons, although the United States accounts for about 5% of the world’s population. The U.S. rate of incarceration, with nearly 1 of every 100 adults in prison or jail, is 5 to 10 times higher than rates in Western Europe and other democracies. The growth in incarceration rates in the United States over the past 40 years is historically unprecedented and internationally unique.”

Preface. This National Research Council 465-page report may be the most comprehensive study of the U.S. prison system there is. It will make you cry. I’ve excerpted about one-sixth of it below. It is shocking that the “U.S. penal population of 2.2 million adults is the largest in the world. In 2012, close to 25% of the world’s prisoners were held in American prisons, although the United States accounts for about 5% of the world’s population. The U.S. rate of incarceration, with nearly 1 of every 100 adults in prison or jail, is 5 to 10 times higher than rates in Western Europe and other democracies. The growth in incarceration rates in the United States over the past 40 years is historically unprecedented and internationally unique.”

Here are a few of the political consequences of incarceration that have affected all of us:

Manza and Uggen (2006, p. 192) estimate that if Florida had not banned an estimated 800,000 former felons from voting in the 2000 election, Al Gore would likely have carried the state and won the White House, and also contend that the Democratic Party would likely have controlled the U.S. Senate for much of the 1990s, as well as several additional governorships, had former felons been permitted to vote.

After the Civil War, public officials carefully tailored their felon disenfranchisement laws so as to circumvent the Fifteenth Amendment and thus restrict the vote of newly freed blacks. The U.S. Supreme Court has generally upheld such laws, except in instances of clear and convincing evidence that they were enacted with a racially discriminatory intent.

As of 2010, nearly 6 million people were disenfranchised because of a felony conviction —a 5-fold increase since 1976. This figure represents about 2.5% of the total U. S. voting-age population, or 1 in 40 adults. One of every 13 African Americans of voting age, or approximately 7.7%, is disenfranchised. This rate is about three times greater than the disenfranchisement rate for non-African Americans

The distribution of disenfranchised felons varies greatly by state, race, and ethnicity because of variations in state disenfranchisement statutes and state incarceration rates. In the three states with the highest rates of African American disenfranchisement—Florida, Kentucky, and Virginia—more than one in five African Americans is disenfranchised. In Arizona and Florida, an estimated 9 to 10% of voting-age Latino citizens are disenfranchised because of their criminal record.

The evidence of political inequities in redistricting due to the way the U.S. Census Bureau counts prisoners is “compelling” according to a report of the National Research Council. If prisoners in Texas were enumerated in their home county rather than where they are incarcerated, Houston would likely have one additional state representative in the latest round of redistricting. Likewise, an analysis by the Prison Policy Initiative finds that several Republican seats in the New York State Senate would be in jeopardy if prisoners in upstate correctional institutions were counted in their home neighborhood in New York City.

Clearly the “what to do” advice is stay out of jail! Though you might also want to be there after collapse. I stumbled on a survival site when doing an internet search on prisons that suggested during the worst of collapse a prison is one of the few defendable and most impregnable of structures (though apartments are to a lesser extent as well, that’s why in crime-ridden third world countries the wealthy live in them rather than houses which are easily invated).

NRC. 2014. The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences. National Research Council, the National Academies Press. 465 pages

Summary

After decades of stability from the 1920s to the early 1970s, the rate of incarceration in the United States more than quadrupled in the past four decades. Our work encompassed research on, and analyses of, the proximate causes of the dramatic rise in the prison population and the societal dynamics that supported those proximate causes. Our analysis reviewed evidence of the effects of high rates of incarceration on public safety as well as those in prison, their families, and the communities from which these men and women originate and to which they return. We also examined the effects on U.S. society.

Issues regarding criminal punishment necessarily involve ideas about justice, fairness, and just deserts. Accordingly, this report includes a review of established principles of jurisprudence and governance that have historically guided society’s use of incarceration.

FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS

From 1973 to 2009, the state and federal prison populations that are the main focus of this study rose steadily, from about 200,000 to 1.5 million, declining slightly in the following 4 years. In addition to the men and women serving prison time for felonies, another 700,000 are held daily in local jails. In recent years, the federal prison system has continued to expand, while the state incarceration rate has declined. Between 2006 and 2011, more than half the states reduced their prison populations, and in 10 states the number of people incarcerated fell by 10% or more.

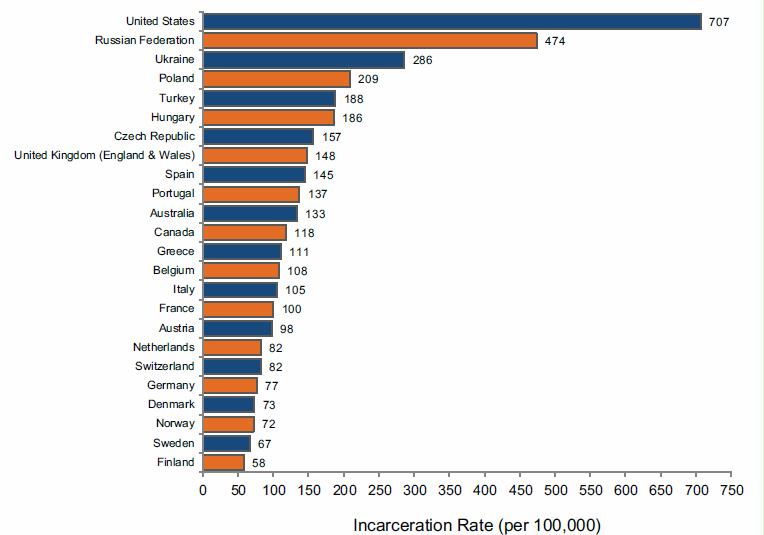

The U.S. penal population of 2.2 million adults is the largest in the world. In 2012, close to 25% of the world’s prisoners were held in American prisons, although the United States accounts for about 5% of the world’s population. The U.S. rate of incarceration, with nearly 1 of every 100 adults in prison or jail, is 5 to 10 times higher than rates in Western Europe and other democracies.

The growth in incarceration rates in the United States over the past 40 years is historically unprecedented and internationally unique.

Those who are incarcerated in U.S. prisons come largely from the most disadvantaged segments of the population. They comprise mainly minority men under age 40, poorly educated, and often carrying additional deficits of drug and alcohol addiction, mental and physical illness, and a lack of work preparation or experience. Their criminal responsibility is real, but it is embedded in a context of social and economic disadvantage.

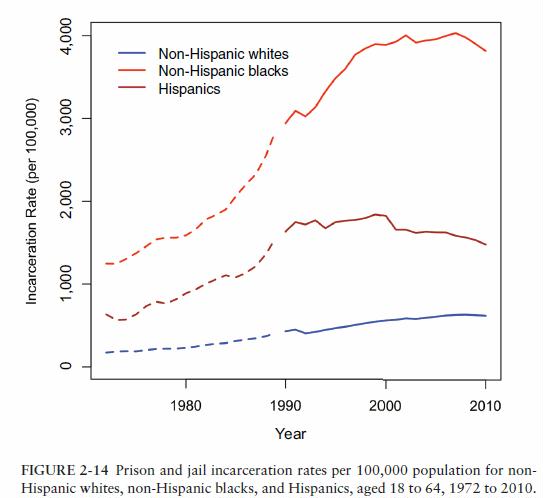

More than half the prison population is black or Hispanic. In 2010, blacks were incarcerated at six times and Hispanics at three times the rate for non-Hispanic whites.

Causes

By the time incarceration rates began to grow in the early 1970s, U.S. society had passed through a tumultuous period of social and political change. Decades of rising crime accompanied a period of intense political conflict and a profound transformation of U.S. race relations. The problem of crime gained a prominent place in national policy debates. Crime and race were sometimes conflated in political conversation.

In the 1960s and 1970s, a changed political climate provided the context for a series of policy choices. Across all branches and levels of government, criminal processing and sentencing expanded the use of incarceration in a number of ways: prison time was increasingly required for lesser offenses; time served was significantly increased for violent crimes and for repeat offenders; and drug crimes, particularly street dealing in urban areas, became more severely policed and punished. These changes in punishment policy were the main and proximate drivers of the growth in incarceration. In the 1970s, the numbers of arrests and court caseloads increased, and prosecutors and judges became harsher in their charging and sentencing. In the 1980s, convicted defendants became more likely to serve prison time. More than half of the growth in state imprisonment during this period was driven by the increased likelihood of incarceration given an arrest. Arrest rates for drug offenses climbed in the 1970s, and mandatory prison time for these offenses became more common in the 1980s.

During the 1980s, the U.S. Congress and most state legislatures enacted laws mandating lengthy prison sentences—often of 5, 10, and 20 years or longer—for drug offenses, violent offenses, and “career criminals.” In the 1990s, Congress and more than one-half of the states enacted “three strikes and you’re out” laws that mandated minimum sentences of 25 years or longer for affected offenders. A majority of states enacted “truth-in-sentencing” laws requiring affected offenders to serve at least 85% of their nominal prison sentences. The Congress enacted such a law in 1984.

These changes in sentencing reflected a consensus that viewed incarceration as a key instrument for crime control. Yet over the four decades when incarceration rates steadily rose, U.S. crime rates showed no clear trend: the rate of violent crime rose, then fell, rose again, then declined sharply.

The best single proximate explanation of the rise in incarceration is not rising crime rates, but the policy choices made by legislators to greatly increase the use of imprisonment as a response to crime. Mandatory prison sentences, intensified enforcement of drug laws, and long sentences contributed not only to overall high rates of incarceration, but also especially to extraordinary rates of incarceration in black and Latino communities.

Intensified enforcement of drug laws subjected blacks, more than whites, to new mandatory minimum sentences—despite lower levels of drug use and no higher demonstrated levels of trafficking among the black than the white population. Blacks had long been more likely than whites to be arrested for violence. But three strikes, truth-in-sentencing, and related laws have likely increased sentences and time served for blacks more than whites. As a consequence, the absolute disparities in incarceration increased, and imprisonment became common for young minority men, particularly those with little schooling.

CONCLUSION: The unprecedented rise in incarceration rates can be attributed to an increasingly punitive political climate surrounding criminal justice policy formed in a period of rising crime and rapid social change. This provided the context for a series of policy choices —across all branches and levels of government—that significantly increased sentence lengths, required prison time for minor offenses, and intensified punishment for drug crimes.

Consequences. Relationships among incarceration, crime, sentencing policy, social inequality, and numerous other variables influencing the growth of incarceration are complex, change across time and place, and interact with each other. As a result, estimating the social consequences of high rates of incarceration, including the effects on crime, is extremely challenging. Because of the challenge of separating cause and effect from an array of social forces, studies examining the impact of incarceration on crime have produced divergent findings. Most studies conclude that rising incarceration rates reduced crime, but the evidence does not clearly show by how much. A number of studies also find that the crime-reducing effects of incarceration become smaller as the incarceration rate grows, although this may reflect the aging of prison populations.

The increase in incarceration may have caused a decrease in crime, but the magnitude of the reduction is highly uncertain and the results of most studies suggest it was unlikely to have been large.

Much research on the crime effects of incarceration attempts to measure reductions in crime that might result from deterrence and incapacitation. Long sentences characterize the period of high incarceration rates, but research on deterrence suggests that would-be offenders are deterred more by the risk of being caught than by the severity of the penalty they would face if arrested and convicted. High rates of incarceration may have reduced crime rates through incapacitation (locking up people who might otherwise commit crimes), although there is no strong consensus on the magnitude of this effect. And because offending declines markedly with age, the incapacitation effect of very long sentences is likely to be small.

The incremental deterrent effect of increases in lengthy prison sentences is modest at best. Because recidivism rates decline markedly with age, lengthy prison sentences, unless they specifically target very high-rate or extremely dangerous offenders, are an inefficient approach to preventing crime by incapacitation.

The distribution of incarceration across the population is highly uneven. As noted above, regardless of race or ethnicity, prison and jail inmates are drawn mainly from the least educated segments of society. Among white male high school dropouts born in the late 1970s, about one-third are estimated to have served time in prison by their mid-30s. Yet incarceration rates have reached even higher levels among young black men with little schooling: among black male high school dropouts, about two-thirds have a prison record by that same age—more than twice the rate for their white counterparts. The pervasiveness of imprisonment among men with very little schooling is historically unprecedented, emerging only in the past two decades.

Much of the significance of the social and economic consequences of incarceration is rooted in the high absolute level of incarceration for minority groups and in the large racial disparities in incarceration rates. In the era of high incarceration rates, prison admission and return have become commonplace in minority neighborhoods characterized by high levels of crime, poverty, family instability, poor health, and residential segregation. Racial disparities in incarceration have tended to differentiate the life chances and civic participation of blacks, in particular, from those of most other Americans.

People who live in poor and minority communities have always had substantially higher rates of incarceration than other groups. As a consequence, the effects of harsh penal policies in the past 40 years have fallen most heavily on blacks and Hispanics, especially the poorest.

Coming from some of the most disadvantaged segments of society, many of the incarcerated entered prison in unsound physical and mental health. The poor health status of the inmate population serves as a basic marker of its social disadvantage and underlines the contemporary importance of prisons as public health institutions. Incarceration is associated with overlapping afflictions of substance use, mental illness, and risk for infectious diseases (HIV, viral hepatitis, sexually transmitted diseases, and others). This situation creates an enormous challenge for the provision of health care for inmates, although it also provides opportunities for screening, diagnosis, treatment, and linkage to treatment after release. Prison conditions can be especially hard on some people, particularly those with mental illness, causing severe psychological stress. Although levels of lethal violence in prisons have declined, conditions have deteriorated in some other ways. Increased rates of incarceration have been accompanied by overcrowding and decreased opportunity for rehabilitative programs, as well as a growing burden on medical and mental health services.

Many state prisons and the Federal Bureau of Prisons operate at or above 100% of their designed capacity. With overcrowding, cells designed for a single inmate often house two and sometimes three people. The concern that overcrowding would create more violent environments did not materialize during the period of rising incarceration rates: rather, as the rates rose, the numbers of riots and homicides within prisons declined. Nonetheless, research has found overcrowding, particularly when it persists at high levels, to be associated with a range of poor consequences for health and behavior and an increased risk of suicide. In many cases, prison provides far less medical care and rehabilitative programming than is needed.

Incarceration is strongly correlated with negative social and economic outcomes for former prisoners and their families. Men with a criminal record often experience reduced earnings and employment after prison. Fathers’ incarceration and family hardship, including housing insecurity and behavioral problems in children, are strongly related. The partners and children of prisoners are particularly likely to experience adverse outcomes if the men were positively involved with their families prior to incarceration.

From 1980 to 2000, the number of children with incarcerated fathers increased from about 350,000 to 2.1 million—about 3% of all U.S. children. From 1991 to 2007, the number of children with a father or mother in prison increased 77% and 131%, respectively.

The rise in incarceration rates marked a massive expansion of the role of the justice system in the nation’s poorest communities. Many of those entering prison come from and will return to these communities. When they return, their lives often continue to be characterized by violence, joblessness, substance abuse, family breakdown, and neighborhood disadvantage. The best evidence to date leaves uncertain the extent to which these conditions of life are themselves exacerbated by incarceration.

Given the evidence, crime reduction and socioeconomic disadvantage are both plausible outcomes of increased incarceration, but estimates of the size of these effects range widely. The vast expansion of the criminal justice system has created a large population whose access to public benefits, occupations, vocational licenses, and the franchise is limited by a criminal conviction. High rates of incarceration are associated with lower levels of civic and political engagement among former prisoners and their families and friends than among others in their communities. Disfranchisement of former prisoners and the way prisoners are enumerated in the U.S. census combine to weaken the power of low-income and minority communities. For these people, the quality of citizenship—the quality of their membership in American society and their relationship to public institutions—has been impaired. These developments have created a highly distinct political and legal universe for a large segment of the U.S. population.

The consequences of the decades-long build-up of the U.S. prison population have been felt most acutely in minority communities in urban areas already experiencing significant social, economic, and public health disadvantages. For policy and public life, the magnitude of the consequences of incarceration may be less important than the overwhelming evidence of this correlation. In communities of concentrated disadvantage—characterized by high rates of poverty, violent crime, mental illness and drug addiction— the United States embarked on a massive and unique intensification of criminal punishment. Although many questions remain unanswered, the greatest significance of the era of high incarceration rates may lie in that simple descriptive fact.

Policies regulating criminal punishment cannot be determined only by the scientific evidence. The decision to deprive another human being of his or her liberty is, at root, anchored in beliefs about the relationship between the individual and society and the role of criminal sanctions in preserving the social compact. Thus, sound policies on crime and incarceration will reflect a combination of science and fundamental principles.

GUIDING PRINCIPLES. A broad discussion of principles has been notably absent from the nation’s recent policy debates on the use of imprisonment. Beginning in the early 1970s, in a time of rising violence and rapid social change, policy makers turned to incarceration to denounce the moral insult of crime and to deter and incapacitate criminals. As offender accountability and crime control were emphasized, principles that previously had limited the severity of punishment were eclipsed, and punishments became more severe. Yet a balanced understanding of the role of imprisonment in society recognizes that the deprivation of personal liberty is one of the harshest penalties society can impose. Even under the best conditions, incarceration can do great harm—not only to those who are imprisoned, but also more broadly to families, communities, and society as a whole. Moreover, the forcible deprivation of liberty through incarceration is vulnerable to misuse, threatening the basic principles that underpin the legitimacy of prisons.

We believe that as policy makers and the public consider the implications of the findings presented in this report, they also should consider the following four principles whose application would constrain the use of incarceration: • Proportionality: Criminal offenses should be sentenced in proportion to their seriousness. • Parsimony: The period of confinement should be sufficient but not greater than necessary to achieve the goals of sentencing policy. • Citizenship: The conditions and consequences of imprisonment should not be so severe or lasting as to violate one’s fundamental status as a member of society. • Social justice: Prisons should be instruments of justice, and as such their collective effect should be to promote and not undermine society’s aspirations for a fair distribution of rights, resources, and opportunities.

POLICY IMPLICATIONS AND RECOMMENDATION. We have looked at an anomalous period in U.S. history, examining why it arose and with what consequences. Given the available evidence regarding the causes and consequences of high incarceration rates, and guided by fundamental normative principles regarding the appropriate use of imprisonment as punishment, we believe that the policies leading to high incarceration rates are not serving the country well. We are concerned that the United States has gone past the point where the numbers of people in prison can be justified by social benefits. Indeed, we believe that the high rates of incarceration themselves constitute a source of injustice and social harm. A criminal justice system that made less use of incarceration might better achieve its aims than a harsher, more punitive system

RECOMMENDATION: Given the small crime prevention effects of long prison sentences and the possibly high financial, social, and human costs of incarceration, federal and state policy makers should revise current criminal justice policies to significantly reduce the rate of incarceration in the United States. In particular, they should reexamine policies regarding mandatory prison sentences and long sentences. Policy makers should also take steps to improve the experience of incarcerated men and women and reduce unnecessary harm to their families and their communities.

We recommend such a systematic review of penal and related policies with the goals of achieving a significant reduction in the number of people in prison in the United States and providing better conditions for those in prison. To promote these goals, jurisdictions would need to review a range of programs, including community-based alternatives to incarceration, probation and parole, prisoner reentry support, and diversion from prosecution, as well as crime prevention initiatives.

To minimize harm from incarceration, we urge reconsideration of the conditions of confinement and programs in prisons. Given that nearly all prisoners are eventually released, attention should be paid to how prisons can better serve society by addressing the need of prisoners to adjust to life following release and supporting their successful reintegration with their families and communities. Reviews of the conditions and programs in prisons would benefit from being open to public scrutiny. One approach would be to subject prisons to systematic ratings related to their public purposes. Such ratings could incorporate universal standards that recognize the humanity and citizenship of prisoners and the obligation to prepare them for life after prison.

After decades of stability from the 1920s to the early 1970s, the rate of incarceration in the United States has increased to a rate more than four times higher than in 1972. In 1972, the U.S. incarceration rate—the number in prisons and local jails per 100,000 population—stood at 161. After peaking in 2009, the number of people in state and federal prisons fell slightly through 2012. Still, in 2012, the incarceration rate was 707 per 100,000, a total of 2.23 million people in custody (Glaze and Herberman, 2013). Nearly 1 of every 100 adults in the U.S. is in prison or jail.

The large racial disparity in incarceration is striking. Of those behind bars in 2011, about 60% were minorities (858,000 blacks and 464,000 Hispanics)

To preserve order and safety, to affirm norms of lawful conduct, and to help remedy criminal behavior, we built lockups, detention centers, asylums, jails, and prisons. These institutions reflect how a society through its political process has negotiated a compromise between order and freedom. Incarceration is in many ways a foundational institution, being the last resort of a state’s authority in the performance of its many other functions. As many have remarked, the use and character of incarceration thus reveals something fundamental about a society’s level of civilization and the quality of citizenship (de Beaumont and de Tocqueville, 1970; Churchill, 1910; Dostoevsky, 1861).

Crime and punishment are social and legal constructs. Their nature and meanings change over time and differ from one society (and one person) to another. In American jurisprudence, a prison sentence serves three possible purposes. First, the purpose of a prison sentence may be understood primarily as retribution, or “just deserts,” meaning that the severity of a given crime requires deprivation of the liberty of the person found guilty of that crime. Second, a prison sentence may be justified as a way of preventing crime, either through deterrence of the individual sentenced (specific deterrence), deterrence of others in society at large who may be inclined to offend (general deterrence), or avoidance of crimes that might otherwise have been committed by that individual absent incarceration (incapacitation). Finally, a prison sentence may be deemed justified as a means of preventing future crimes through the rehabilitation of the individual incarcerated. Of course, these rationales are not mutually exclusive.

Throughout U.S. history, the emphasis on one or another rationale for incarceration has shifted significantly, and it continues to change. As a consequence, the conditions of confinement and the experience of returning to society also have changed. To understand the effects of the rise in incarceration, one must examine how prison environments have changed as the numbers of prisoners have increased and how this changed environment may lead to different outcomes for the individuals incarcerated.

Whereas the jurisprudence of incarceration emphasizes the purposes of retribution, deterrence, incapacitation, and rehabilitation, criminal punishment also provides a vivid moral symbol, publicly condemning criminal conduct. Thus the French sociologist Emile Durkheim (1984) argued that penal law affirms basic values and helps build social solidarity. By this account, punishment activates society’s moral sentiments and reinforces the collective sense of right and wrong.

Critics have objected that, rather than reflecting “society as a whole,” institutions of punishment under real conditions of social and economic inequality burden the disadvantaged. From this perspective, prisons and jails reflect and perhaps exacerbate social inequalities rather than promote social solidarity.

Some scholars have argued that, in light of this nation’s long history of troubled race relations, it is especially important to consider whether prison and other punishments unfairly burden African Americans and other minority groups. If so, the justice system only reinforces historical inequalities, thereby undermining the social compact that should undergird the nation’s laws.

Prisons also can support the rehabilitation of those incarcerated so that after release, they are more likely to live in a law-abiding way and reintegrate successfully into the rhythms of work, family, and civic engagement. In this narrower view of the instrumental value of incarceration policies, the effectiveness of prisons is measured by such outcomes as lower rates of recidivism and higher rates of employment, supportive family connections, improved health outcomes, and the standing of the formerly incarcerated as citizens in the community. The relevant scholarly literature focuses on issues of the availability and effectiveness of programs; the impact of the prison environment on the self-concept, behavior, and human capital of those incarcerated; and the experience of leaving prison and returning home.

Yet another stream of scholarly inquiry examines the role of the criminal justice system, and in particular the role of prisons, in controlling entire categories or communities of people. In this view, the laws of society and the instruments of punishment have been used throughout history to sustain those in power by suppressing active opposition to entrenched interests and deterring challenges to the status quo. This scholarly literature has examined the role of the justice system—including the definition of crimes by legislatures, enforcement of laws by the police, and uses of incarceration—in dealing with new immigrant groups, the labor and civil rights movements, the behavior of the mentally ill, and the use of alcohol and illegal drugs, to cite some examples. In recent years, scholars in this tradition have focused on the impact of the justice system on racial minorities in the United States and specifically on the impact of recent high rates of incarceration on the aspiration for racial equality. Researchers who study the power relations of society reflected in the criminal justice system often observe that the poor, minorities, and the marginal are seen as dangerous or undeserving. In these cases, the majority will support harsh punishments entailing long sentences and the use of imprisonment for lesser offenses. The effect of incarceration and other punishments used in this way may be to reproduce and deepen existing social and economic inequalities.

Because incarceration imposes pain and loss on both those sentenced and, frequently, their families and others, these costs also must be weighed against its social benefits in determining when or whether the deprivation of liberty is justified.

Because incarceration encompasses a range of experiences that vary widely across individuals and from one era or place to another, its effects are difficult to assess. This variation arises not only from differences in the legal terms of sentences, such as length and conditions for release, but also from differences in the conditions of confinement and after release. Harsh or abusive prison environments can cause damage to those subjected to them, just as environments that offer treatment and opportunities to learn and work can provide them with hope, skills, and other assets. So while we talk about incarceration as a single phenomenon, it in fact describes a wide range of experiences that may have very different effects.

Our analysis of both causes and consequences (discussed below) must remain provisional because the growth of incarceration is so recent, its effects are still unfolding, and the level and uses of incarceration at a given moment in time are the result of a complex set of past and ongoing social and political changes. Beginning in the 1960s, a complex combination of organized protests, urban riots, violent crime and drug use, the collapse of urban schools, and many other factors contributed to declining economic opportunities in many neighborhoods and too often to greater fear of crime. After 1970, a wave of heavy industry closings and mass layoffs resulting from technological changes, international competition, and shifting markets contributed to the elimination of many relatively high-paying jobs for less educated workers with specialized skills. Places hardest hit by the wave of industrial losses also experienced large and sustained increases in crime. In the 1980s, a wave of crack cocaine use and related street crime hit many of the nation’s already distressed inner cities.

In the wake of these and other structural shifts, employment fell among young people with little schooling and work experience. The income gap between unskilled and skilled workers widened. Large-scale migrations from rural to urban areas and an influx of lower-skilled undocumented workers from Mexico and Central America coincided with this widening inequality. In past decades, then, as growing percentages of all ethnic and racial groups have graduated from high school and went on to higher education, those who dropped out were left further behind with fewer options for earning a living.

In the past two decades of the period of the rise in incarceration rates, new attention to illegal immigration and to sex offenses led to new laws and penalties, contributing to growing numbers detained, convicted, and sentenced to prison for these offenses.

A full description of this complex and evolving social context for the expanded use of prison as a response to crime in the United States is beyond the scope of this study. Nonetheless, it is important to examine this history to better understand the rising use of imprisonment over nearly four decades. The committee does not view the growth of incarceration as an inevitable product of these larger social changes. The United States has experienced other periods of sweeping social change and disorder in which incarceration rates did not rise. During the recent period, moreover, the United States stood apart from other modern industrial democracies in the direction it took. To understand how U.S. incarceration rates reached their current level, the committee examined and weighed evidence of various kinds, drawing on the methods of historians, economists, and political scientists, as well as other social scientists.

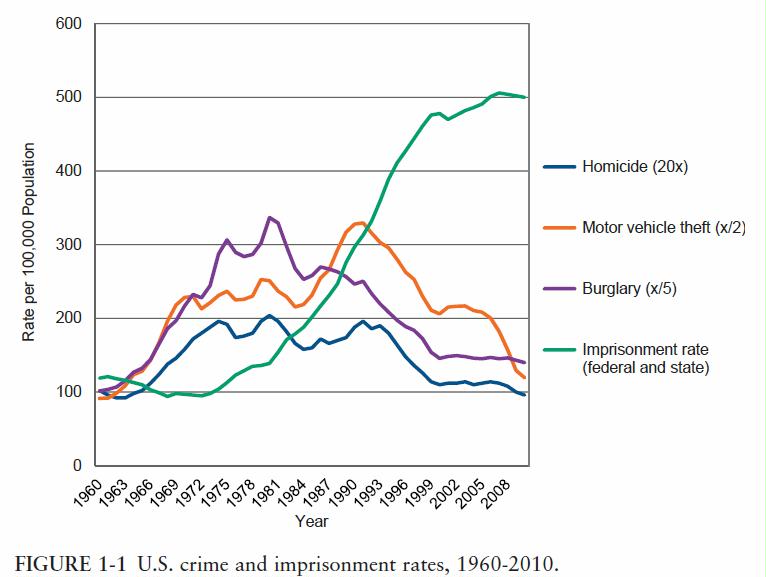

As rates of many major crime types rose and fell for more than five decades, incarceration rates started to rise nationally in 1973 and continued to rise for 40 years, stabilizing only recently (Tonry, 2012; see Figure 1-1). Some may compare the decline in crime rates after 1980 and again in the 1990s with the increase in incarceration rates and infer that incarceration greatly reduces crime. However, studies of crime trends that consider many possible influences, including changes in incarceration rates, have had limited success separating different causes.

600 500 400 Homicide (20x) Motor vehicle theft (x/2) 300 Burglary (x/5) 200 Imprisonment rate (federal and state) 100 0 Year FIGURE 1-1 U.S. crime and imprisonment rates, 1960-2010.

Depending, among other things, on the conditions and duration of confinement and release, imprisonment can be humane and even helpful. Incarceration can provide time for reflection and personal growth, access to better health care and treatment of drug dependency or illness, respite from toxic environments or situations, and opportunities to learn and acquire skills. Alternatively, prison can be harmful and degrading, exposing the confined to criminal influence, violence, and humiliation; isolating them from nurturing human contact and personal responsibility; and leaving them poorly equipped for life outside.

A further limit on analysis of prison conditions is imposed by barriers to researchers’ access to prisons. In earlier times, scholars were given broad access to prisons, prisoners, and corrections officers. By contrast, the contemporary prison has not been the subject of sustained empirical inquiry, perhaps reflecting less interest on the part of researchers and wariness on the part of prison administrators. The lack of research access, combined with cutbacks in other forms of outside review—journalistic investigations of life on the inside and judicial review of legal challenges to prison conditions—means that the nation’s prison systems are less open than before to public scrutiny. Finally, prisons have not been subjected to the same degree of regular reporting and public scrutiny based on transparent, published standards of performance as some other major public institutions, such as schools and hospitals.

Members of this committee share the view that the inherent severity of incarceration as a punishment—including the harm it often does to prisoners, their families, and communities—argues for limiting its use to cases where alternatives are less effective in achieving the same social ends. The evidence reviewed in this report reveals that the costs of today’s unprecedented rate of incarceration, particularly the long prison sentences imposed under recent sentencing laws, outweigh the observable benefits. We are conscious as well that a key feature of today’s high rate of incarceration is that large proportions of poor, less educated African American and Hispanic men are likely to be in jail or prison at some time in their lives. Indeed, for many poorly educated African American and Hispanic men, coercion is the most salient of their encounters with public authority. These findings led us to look for better policy choices.

Through the middle of the twentieth century, from 1925 to 1972, the combined state and federal imprisonment rate, excluding jails, fluctuated around 110 per 100,000 population, rising to a high of 137 in 1939.

The historically high U.S. incarceration rate also is unsurpassed internationally. European statistics on incarceration are compiled by the Council of Europe, and international incarceration rates are recorded as well by the International Centre for Prison Studies (IPS) at the University of Essex in the United Kingdom.

The 2011 IPS data show approximately 10.1 million people (including juveniles) incarcerated worldwide. In 2009, the United States (2.29 million) accounted for about 23% of the world total. In 2012, the U.S. incarceration rate per 100,000 population was again the highest reported (707), significantly exceeding the next largest per capita rates of Rwanda (492) and Russia (474).

Western European democracies have incarceration rates that, taken together, average around 100 per 100,000, one-seventh the rate of the United States. The former state socialist countries have very high incarceration rates by European standards, two to five times higher than the rates of Western Europe. But even the imprisonment rate for the Russian Federation is only about two-thirds that of the United States. In short, the current U.S. rate of incarceration is unprecedented by both historical and comparative standards.

Trends in Prison and Jail Populations

Discussion and analysis of the U.S. penal system generally focus on three main institutions for adult penal confinement: state prisons, federal prisons, and local jails. State prisons are run by state departments of correction, holding sentenced inmates serving time for felony offenses, usually longer than a year. Federal prisons are run by the U.S. Bureau of Prisons and hold prisoners who have been convicted of federal crimes and pretrial detainees. Local jails usually are county or municipal facilities that incarcerate defendants prior to trial, and also hold those serving short sentences, typically under a year. This sketch captures only several small states (Alaska, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Rhode Island, Vermont) hold all inmates (including those awaiting trial and those serving both short and long sentences) under the jurisdiction of a single state correctional agency. In Massachusetts, county houses of correction incarcerate those serving up to 3 years. Many prisons have separate units for pretrial populations. But this simple description does not encompass the nation’s entire custodial population. Minors, under 18 years old, typically are held in separate facilities under the authority of juvenile justice agencies. Additional adults are held in police lockups, immigration detention facilities, and military prisons and under civil commitment to state mental hospitals.

Trends in the State Prison Population

State prisons accounted for around 57% of the total adult incarcerated population in 2012, confining mainly those serving time for felony convictions and parolees reincarcerated for violating their parole terms.

The state prison population can be broadly divided into three offense categories: violent offenses (including murder, rape, and robbery), property offenses (primarily auto vehicle theft, burglary, and larceny/theft), and drug offenses (manufacturing, possession, and sale). In 2009, about 716,000 of 1.36 million state prison inmates had been convicted of violent crimes.

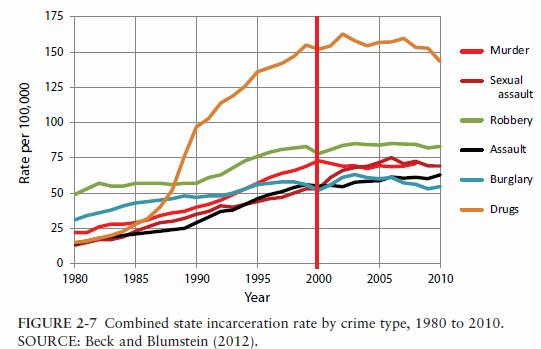

The most marked change in the composition of the state prison population involves the large increase in the number of those convicted for drug offenses. At the beginning of the prison expansion, drug offenses accounted for a very small percentage of the state prison population.

In 1996, 23% of state prisoners were convicted of drug offenses. By the end of 2010, 17.4% of state prisoners had been convicted of drug crimes.

Trends in the Federal Prison Population

Federal prisons incarcerate people sentenced for federal crimes, so the mix of offenses among their populations differs greatly from that of state prisons. The main categories of federal crimes involve robbery, fraud, drugs, weapons, and immigration. These five categories represented 88% of all sentenced federal inmates in 2010.

Federal crimes are quite different from those discussed above for state prisons. Robbery entails primarily bank robbery involving federally insured institutions; fraud includes violations of statutes pertaining to lending/credit institutions, interstate wire/communications, forgery, embezzlement, and counterfeiting; drug offenses typically involve manufacturing, importation, export, distribution, or dispensing of controlled substances; weapons offenses concern the manufacturing, importation, possession, receipt, and licensing of firearms and cases involving a crime of violence or drug trafficking when committed with a deadly weapon; and immigration offenses include primarily unlawful entry and reentry, with a smaller fraction involving misuse of visas and transporting or harboring of illegal entrants (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2012a).

At least one-half of the remainder comprised those sentenced for possession/trafficking in obscene materials (3.7%) or for racketeering/extortion (2.7%) (Bureau of Justice Statistics, n.d.-b).

Trends in the Jail Population

In 2012, one-third of the adult incarcerated population was housed in local jails. Jail is often the gateway to imprisonment. Jails serve local communities and hold those who have been arrested, have refused or been unable to pay bail, and are awaiting trial. They also hold those accused of misdemeanor offenses—often arrested for drug-related offenses or public disorder—and those sentenced to less than a year. John Irwin’s (1970) study of jail describes its occupants as poor, undereducated, unemployed, socially detached, and disreputable. Because of their very low socioeconomic status, jail inhabitants, in Irwin’s language, are “the rabble,” and others have similarly described them as “social trash,” “dregs,” and “riff raff”. The jail population is about one-half the size of the combined state and federal prison population and since the early 1970s has grown about as rapidly as the state prison population. It is concentrated in a relatively small number of large urban counties. The short sentences and pretrial detention of the jail population create a high turnover and vast numbers of admissions. BJS estimates that in 2012, the jail population totaled around 745,000, with about 60% of that population turning over each week.

In 2012, one-third of the adult incarcerated population was housed in local jails. Jail is often the gateway to imprisonment. Jails serve local communities and hold those who have been arrested, have refused or been unable to pay bail, and are awaiting trial. They also hold those accused of misdemeanor offenses—often arrested for drug-related offenses or public disorder—and those sentenced to less than a year. John Irwin’s (1970) study of jail describes its occupants as poor, undereducated, unemployed, socially detached, and disreputable. Because of their very low socioeconomic status, jail inhabitants, in Irwin’s language, are “the rabble,” and others have similarly described them as “social trash,” “dregs,” and “riff raff”. The jail population is about one-half the size of the combined state and federal prison population and since the early 1970s has grown about as rapidly as the state prison population. It is concentrated in a relatively small number of large urban counties. The short sentences and pretrial detention of the jail population create a high turnover and vast numbers of admissions. BJS estimates that in 2012, the jail population totaled around 745,000, with about 60% of that population turning over each week.

In 2010, the nation’s jails admitted around 13 million inmates. With such high turnover, the growth of the jail population has greatly expanded the footprint of penal confinement.

The Increasing Scope of Correctional Supervision

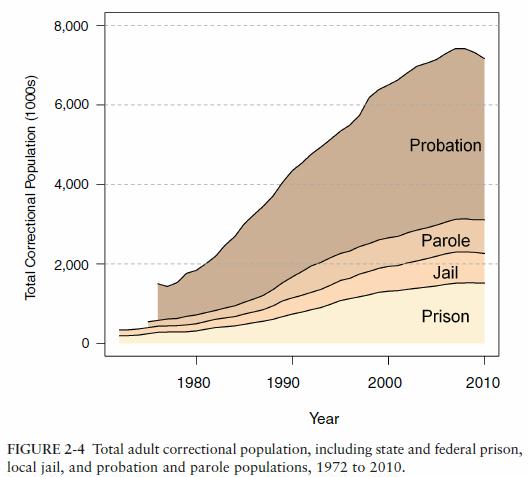

The significant increase in the number of people behind bars since 1972 occurred in parallel with the expansion of community corrections. Figure 2-4 shows the scale of the entire adult correctional system.

Correctional supervision encompasses prisons and jails and also the community supervision of those on probation and parole. Probation usually supervises people in the community who can, following revocation for breach of conditions, be resentenced to prison or jail.

the probation population increased greatly in absolute terms, from 923,000 in 1976 to 4.06 million in 2010, declining slightly to 3.94 million in 2012.

The large probation and parole populations also expand a significant point of entry into incarceration. If probationers or parolees violate the conditions of their supervision, they risk revocation and subsequent incarceration. In recent decades, an increasing proportion of all state prison admissions have been due to parole violations. As a proportion of all state prison admissions, returning parolees made up about 20% in 1980, rising to 30% by 1991 and remaining between 30 and 40% until 2010. This represents a significant shift in the way the criminal justice system handled criminal offenses, increasing reliance on imprisonment rather than other forms of punishment, supervision, or reintegration. Parole may be revoked for committing a new crime or for violating the conditions of supervision without any new criminal conduct (“technical violators”), or someone on parole may be charged with a new crime and receive a new sentence.

The rising numbers of parole violations contributed to the increase in incarceration rates. The number of parole violators admitted to state prison following new convictions and sentences has remained relatively constant since the early 1990s. The number of technical violators more than doubled from 1990 to 2000. In 2010, the approximately 130,000 people reincarcerated after parole had been revoked for technical violations accounted for about 20% of state admissions. These returns accounted for 23% of all exits from parole that year.

By 2010, slightly more than 7 million U.S. residents, 1 of every 33 adults, were incarcerated in prison or jail or were being supervised on parole or probation.

Variation in Incarceration Rates Among States

Trends in incarceration rates vary greatly among states. While the national imprisonment rate increased nearly 5-fold from 1972 to 2010, state incarceration rates in Maine and Massachusetts slightly more than doubled. At the other end of the spectrum, the rates in Louisiana and Mississippi increased more than 6-fold.

To see the change in trends, it is useful to divide the period since 1972 into two parts: from 1972 to 2000 and from 2000 to 2010 (see Figure 2-5). As discussed above, the period from 1972 to 2000 was a time of rapid growth for state prison populations; the change in incarceration rates in this period is indicated for each state in blue. The largest increases in this period generally occurred in southern and western states. From 1972 to 2000, incarceration rates grew most in Louisiana, Mississippi, Oklahoma, and Texas. In Louisiana, the rate grew by 700 per 100,000 population—more than 10-fold—rising to 801 per 100,000 by 2000, then climbing further to 867 by 2010.

Growth in state incarceration rates was much slower in the northeast and midwest. In Maine and Minnesota, the rates grew by only around 100 per 100,000. These two states had the lowest incarceration rates by 2010—148 for Maine and 185 for Minnesota. In the period since 2000, incarceration rates have grown more slowly across the country. As shown by the red circles in Figure 2-5, a few states have registered very large declines, including Delaware, Georgia, and Texas in the south and New Jersey and New York in the northeast.

The country experienced a large increase in crime from the early 1960s until the 1980s. From the early 1990s, crime rates began to fall broadly for the following two decades. Property and violent crime show roughly similar trends, although the property crime rate peaked in 1979, while violence continued to rise through the mid-1980s after falling in the first half of the decade. Following the broad trends in crime, the homicide rate—widely thought to be the most accurately measured—began to increase from the 1960s, peaking in 1981. Similar to the property crime rate, the homicide rate fluctuated through the 1980s until peaking again in 1991, just below the 1981 level.

Trends in drug arrests followed a different pattern. The drug arrest rate grew very sharply in the 1980s, more than doubling from 1980 to 1989. After a 2-year decline, the drug arrest rate again increased over the next decade, and by 2010 was more than double its level in 1980.

In summary, the growth in incarceration rates beginning in 1973 was preceded for about a decade by a very large increase in crime rates. Incarceration rates showed their strongest period of growth in the 1980s, as violent crime fell through the first half of the decade and then increased in the second. Incarceration rates continued to climb through the 1990s as the violent crime rate began to fall. Finally, in the 2000s, crime rates have remained stable at a low level, while the incarceration rate peaked in 2007, and the incarcerated population peaked in 2010. Thus the very high rates of incarceration that emerged over the past decades cannot simply be ascribed to a higher level of crime today compared with the early 1970s, when the prison boom began.

Most striking, however, is the dramatic increase in the incarceration rate for drug-related crimes. In 1980, imprisonment for drug offenses was rare, with a combined state incarceration rate of 15 per 100,000 population. By 2010, the drug incarceration rate had increased nearly 10-fold to 143 per 100,000. Indeed, the rate of incarceration for the single category of drug-related offenses, excluding local jails and federal prisons, by itself exceeds by 50% the average incarceration rate for all crimes of Western European countries and is twice the average incarceration rate for all crimes, including pretrial detainees, of a significant number of European countries.

Trends in Arrests per Crime

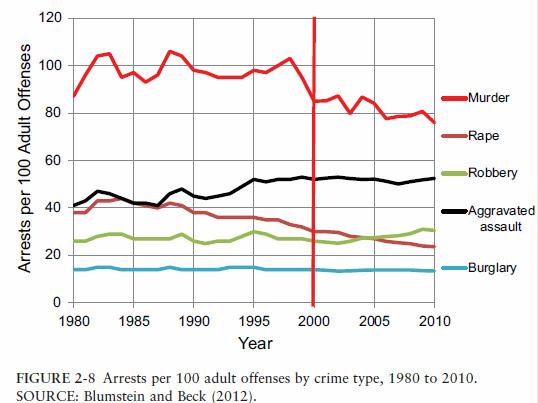

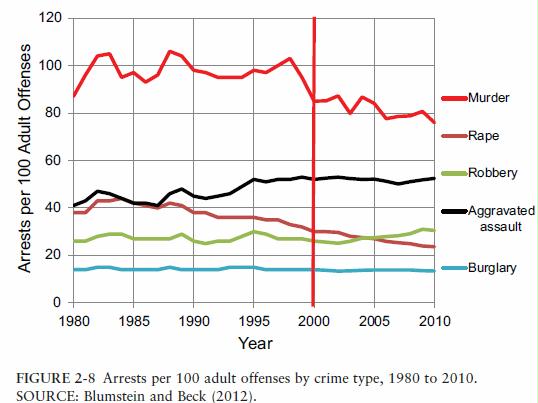

The first point at which the criminal justice system can affect the incarceration rate is through the likelihood of arrest of someone who has committed a crime. The ratio of arrests to crimes is sometimes interpreted as a measure of policing effectiveness or efficiency. Despite significant changes in police technology and management from 1980 to 2010, the ratio of arrests to crimes for the major crime types handled by states and localities has shown little change (see Figure 2-8). For example, the arrest rate for burglaries remained at about 14 arrests per 100 adult offenses. Arrest rates for rape declined rather steadily after 1984 (dropping from a peak of 44 arrests per 100 adult offenses to 24 per 100 by 2010). Robbery arrest rates were steady until 2000 and then increased slightly from 26 to 31 arrests per 100 reported offenses by 2010. In contrast, the arrest rate for aggravated assault grew until 2000 and then remained flat (around 52 arrests per 100 offenses). Murder is the exception, showing a decline in the arrest rate per crime after 2000: arrests for murder were close to 100 per 100 adult offenses until 1998 and then declined to 80 per 100 after 2000. by the measure of the ratio of arrests to crimes, no increase in policing effectiveness occurred from 1980 to 2010 that might explain higher rates of incarceration.

The first point at which the criminal justice system can affect the incarceration rate is through the likelihood of arrest of someone who has committed a crime. The ratio of arrests to crimes is sometimes interpreted as a measure of policing effectiveness or efficiency. Despite significant changes in police technology and management from 1980 to 2010, the ratio of arrests to crimes for the major crime types handled by states and localities has shown little change (see Figure 2-8). For example, the arrest rate for burglaries remained at about 14 arrests per 100 adult offenses. Arrest rates for rape declined rather steadily after 1984 (dropping from a peak of 44 arrests per 100 adult offenses to 24 per 100 by 2010). Robbery arrest rates were steady until 2000 and then increased slightly from 26 to 31 arrests per 100 reported offenses by 2010. In contrast, the arrest rate for aggravated assault grew until 2000 and then remained flat (around 52 arrests per 100 offenses). Murder is the exception, showing a decline in the arrest rate per crime after 2000: arrests for murder were close to 100 per 100 adult offenses until 1998 and then declined to 80 per 100 after 2000. by the measure of the ratio of arrests to crimes, no increase in policing effectiveness occurred from 1980 to 2010 that might explain higher rates of incarceration.

it is clear that drug law enforcement efforts escalated substantially over the period of the prison boom. From 1980 to 1989, the arrest rate for possession and use offenses increased by 89%. After a 2-year period of decline, the drug arrest rate climbed again to peak in 2006, 162% above the 1980 level. The arrest rate fell slightly from this peak, but in 2009 was still more than double the rate in 1980. In 2009, 1.3 million arrests were reported to the UCR for drug use and possession, and another 310,000 arrests were made for the manufacture and sale of drugs.

To foreshadow our later discussion of racial disparity, drug arrest rates, at least since the early 1970s, have always been higher for African Americans than for whites. In the early 1970s, when drug arrest rates were low, blacks were about twice as likely as whites to be arrested for drug crimes. The great growth in drug arrests through the 1980s had a large and disproportionate effect on African Americans. By 1989, arrest rates for blacks had climbed to 1,460 per 100,000, compared with 365 for whites (Western, 2006). Throughout the 1990s, drug arrest rates remained at historically high levels. It might be hypothesized that blacks may be arrested at higher rates for drug crimes because they use drugs at higher rates, but the best available evidence refutes that hypothesis. A long historical trend, dating back to the 1970s, is available from the Monitoring the Future survey of high school seniors. Self-reported drug use among blacks is consistently lower than among whites, a pattern replicated among adults in the National Survey on Drug Abuse. Fewer data are available on drug selling, but self-reports in the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, 1979 and 1997, show a higher level of sales among poor white than poor black youth. In short, the great escalation in drug enforcement that dates from the late 1970s is associated with an increase in the relative arrest rate among African Americans that is unrelated to relative rates of drug use and the limited available evidence on drug dealing.

For the major crime types handled at the state level, the probability that arrest would lead to prison rose over the three decades from 1980 to 2010. The number of prison commitments per 100 adult arrests showed a significant and nearly steady increase (see Figure 2-9), i.e. the rate of commitment to state prison for murder rose from 41 to 92 per 100 arrests, an increase of more than 120%.

Between 1980 and 2010, prison commitments for drug offenses rose 350% (from 2 to 9 per 100 arrests); commitments for sexual assault rose 275% (from 8 to 30 per 100 arrests); and commitments for aggravated assault rose 250% (from 4 to 14 per 100 arrests). State prison commitment rates for burglary and robbery also increased, but these increases were below 100%. These figures indicate that an increased probability that arrest would lead to prison commitment contributed greatly to the rise in incarceration rates between 1980 and 2010.

Time Served

BJS’s analysis of recent trends in the state prison population reveals the growing population serving life and other long sentences. As of the end of 2000, BJS estimated that about 54,000 state prison inmates were serving life sentences, with a median age of under 30. Using a different methodology, a 2013 survey report by the Sentencing Project estimates that more than 150,000 people were serving life sentences in state prison in 2012.

Because of non-stationarity in admission rates and the growing prevalence of very long sentences, the estimates of time served presented below should be viewed as a lower bound on the increase in time served. The downward bias is likely to be largest for violent crimes, for which the growth in very long sentences has been greatest.

The most dramatic change in average time served was for murder, which climbed from 5.0 years in 1981 to 16.9 years in 2000, an increase of 238%. The second largest growth was in time served for sexual assault, which increased 94%, from 3.4 years in 1981 to 6.6 years in 2009; the rate of increase for this crime type was the largest observed during the 2000-2010 decade, adding about 2.5 months each year. The slowest rate of increase in time served was for drug offenses, increasing from 1.6 years in 1981 to 1.9 years in 2000 and then remaining nearly steady through 2009. The stability of time served by those committing drug offenses contrasts with the significant growth in rates of arrest and commitment for drug offenses discussed earlier. Time served may have changed little because short prison sentences were imposed on those committing drug offenses who may previously have served probation or time in jail. Trends in time served for the other three crime types—aggravated assault, burglary, and robbery—showed somewhat similar growth patterns. Averaging 4.0, 2.8, and 2.0 years, respectively, over the entire 1980-2010 period, all had some growth from 1980 to 2000 (83, 41, and 79%, respectively), and all remained nearly stable after 2000

Trends in the Federal System

Growth in the incarceration rate has been larger and more sustained in the federal system than in the states. Between 1980 and 2000, the federal prison population increased by nearly 500%, from 24,363 to 145,416, surpassing the growth in state prison systems.

Growth in the incarceration rate has been larger and more sustained in the federal system than in the states. Between 1980 and 2000, the federal prison population increased by nearly 500%, from 24,363 to 145,416, surpassing the growth in state prison systems.

By 2000, the federal system was the third largest prison system in the nation, behind those of Texas and California. Moreover, while the rapid growth of the states’ prison populations tapered off after 2000, the federal system continued to see a steady increase, becoming the largest system by midyear 2002. By 2010, the federal system, with a population of 209,771 inmates, had grown to be larger than the next largest system, the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, by more than 36,000 inmates. The federal system thus accounts for roughly 10% of the total prison population, but its share has been growing during the prison boom.

Nearly all incarceration in federal prisons is due to federal convictions for robbery; fraud; and drug, weapon, and immigration offenses. During 1980-2000, as with the states, the most dramatic change was in drug-related offending, for which the incarceration rate increased more than 10-fold, from 3 per 100,000 in 1980 to 35 in 2000.

The other two crime types that saw comparably large growth are weapon and immigration offenses, which also increased more than 1,000%; that growth is less apparent because incarceration rates for these offenses started at such low levels in 1980.

The incarceration rate for fraud grew considerably (about 227%) over this period, but still much less than the rates for the other three crime types. The incarceration rate for robbery rose steadily from 2.9 per 100,000 adults and then peaked at 4.6 per 100,000 in 2000. Since 2000, the patterns of growth in incarceration rates have changed.10 With an already high rate of incarceration for drug offenses (35 per 100,000 adults), the increase for these offenses was more modest, up 16% (to 41 per 100,000 adults). At the same time, the dominant source of growth was weapon offenses, up 135% (from 5.2 to 12.2 per 100,000 adults) and immigration offenses, up 40% (from 6.5 to 9.1 per 100,000 adults). Fraud showed little change (up 5.5%), while robbery declined (from 4.6 to 3.2 per 100,000).

RACIAL DISPARITY IN IMPRISONMENT

BJS compiled state and federal prison admission rates for blacks and whites separately in a historical series extending from 1926 to 1986 (Langan, 1991b). The data are available annually from 1926 to 1946 and then intermittently for the post-World War II period until 1986. They show an increase in African American imprisonment from 1926 to 1940, while imprisonment rates were declining for whites. Prison admission rates climbed steeply in the mid-1970s but much more in absolute terms for African Americans than for whites.

In 2010, the imprisonment rate for blacks was 4.6 times that for whites.

Violent Crimes

The relative involvement of blacks in violent crimes has declined significantly since the late 1980s (see Figure 2-12). From 1972 to 1980, the relative share of blacks in arrests for rape and aggravated assault fell by around one-fourth; more modest declines in their share of arrests were recorded for murder and robbery from the 1970s to the 2000s. In the 1970s, blacks accounted for about 54% of all homicide arrests; by the 2000s, that share had fallen below half. For robbery, blacks accounted for 55% of arrests in the 1970s, falling to 52% by the 2000s. For rape, blacks accounted for about 46% of all arrests in the 1970s, declining by 14 percentage points to 32% by the 2000s. The declining share of blacks in violent arrests also is marked for aggravated assaults, which constitute a large majority of violent serious crimes: 41% in the 1970s and just 33% in the 2000s.

These figures show that arrests of blacks for violent crimes constitute smaller percentages of absolute national numbers that are less than half what they were 20 or 30 years ago. Violent crime has been falling in the United States since 1991. In absolute terms, involvement of blacks in violent crime has followed the general pattern; in relative terms, it has fallen substantially more than the overall averages. Yet even though participation of blacks in serious violent crimes has declined significantly, disparities in imprisonment between blacks and whites have not fallen by much; as noted earlier, the incarceration rate for non-Hispanic black males remains seven times that of non-Hispanic whites.

Drug Crimes

The situation for drug offenses is similar to that for violent crime in some respects, but there is a critical difference. Although, according to both arrest and victimization data, blacks have higher rates of involvement than whites in violent crimes, the prevalence of drug use is only slightly higher among blacks than whites for some illicit drugs and slightly lower for others; the difference is not substantial. There is also little evidence, when all drug types are considered, that blacks sell drugs more often than whites. In recent years, drug-related arrest rates for blacks have been three to four times higher than those for whites

In the late 1980s, the rates were six times higher for blacks than for whites

Marijuana arrestees are preponderantly white and are much less likely than heroin and cocaine arrestees to wind up in prison

Incarceration of Hispanics

In 1974, only 12% of the white state prison population and a negligible proportion of blacks reported being of Hispanic origin. By 2004, 24% of the white prison population and around 3% of blacks reported being Hispanic.

Hispanic incarceration rates fall between the rates for non-Hispanic blacks and whites. Over the period of the growth in incarceration rates, the rate has been two to three times higher for Hispanics than for non-Hispanic whites. From 1972 to 1990, the Hispanic rate grew strongly along with incarceration in the rest of the population. Through the 1990s, the Hispanic rate remained roughly flat at around 1,800 per 100,000 of the population aged 18 to 64. Since 2000, the incarceration rate for Hispanics has fallen from 1,820 to just under 1,500.

Rumbaut finds that incarceration rates (and arrest rates) for the immigrant population are relatively low given their poverty rates and education. The highest incarceration rates are found among long-standing national groups—Puerto Ricans and Cubans. For national groups with large shares of recent immigrants—Guatemalans and Salvadorans for example—incarceration rates are very low.

The largest national group, Mexicans, includes significant native-born and foreign-born populations. The incarceration rate indicated in the 2000 census is more than five times higher for native-born U.S. citizens of Mexican descent than for U.S. immigrants born in Mexico.

In fact, U.S. born Mexicans have higher incarceration rates than any other U.S.-born Hispanic group. Overall, the incarceration rate for those of Mexican origin is lower than either Puerto Ricans or Cubans.

This discussion of incarceration of Hispanics has been limited to those in prisons or local jails, and does not encompass immigrant detention outside of those institutions. There is evidence that the latter form of detention has increased significantly in the past decade in specialized immigrant detention facilities but this type of incarceration lies beyond the committee’s charge.

CONCENTRATION OF INCARCERATION BY AGE, SEX, RACE/ETHNICITY, AND EDUCATION

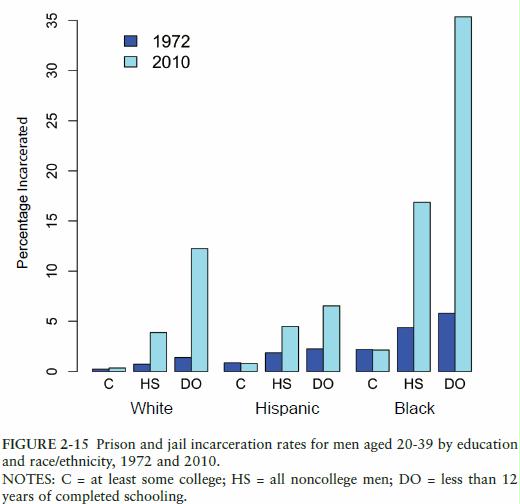

Although racial and ethnic disparities in incarceration are very large, differences by age, sex, and education are even larger. The combined effects of racial and education disparities have produced extraordinarily high incarceration rates among young minority men with little schooling.

The age and gender composition of the incarcerated population has changed since the early 1970s, but the broader demographic significance of the penal system lies in the very high rate of incarceration among prime-age men. The prison population also has aged as time served in prison has increased, but 60% of all prisoners still were under age 40 in 2011

Incarceration rates have increased more rapidly for females than for males since the early 1970s. In 1972, the prison and jail incarceration rate for men was estimated to be 24 times higher than that for women. By 2010, men’s incarceration rate was about 11 times higher.

Women’s incarceration rate had thus risen twice as rapidly as men’s in the period of growing incarceration rates. Yet despite the rapid growth in women’s incarceration, only 7% of all sentenced state and federal prisoners were female by 2011

The racial disparity in incarceration for women is similar to that seen for men. As with the trends for men, the very high rate of incarceration for African American women fell relative to the rate for white women, although the 3 to 1 black-white disparity in women’s imprisonment in 2009 was still substantial

Extremely high incarceration rates had emerged among prime-age noncollege men by 2010 (see Figure 2-15). Around 4% of noncollege white men and a similar proportion of noncollege Hispanic men in this age group were incarcerated in 2010. The education gradient is especially significant for African Americans. Among prime-age black men, around 15% of those with no college and fully a third of high school dropouts were incarcerated on an average day in 2010. Thus at the height of the prison boom in 2010, the incarceration rate for all African Americans is estimated to be 1,300 per 100,000. For black men under age 40 who had dropped out of high school, the incarceration rate is estimated to be more than 25 times higher, at 35,000 per 100,000. Educational inequalities in incarceration rates have increased since 1972

Incarceration rates have barely increased among those who have attended college; nearly all the growth in incarceration is concentrated among those with no college education. The statistics clearly show that prison time has become common for men with little schooling.

It is instructive to compare the risks of imprisonment by age 30-35 for men in two birth cohorts: the first born in 1945-1949, just before the great increase in incarceration rates, and the second born in the late 1970s, growing up through the period of high incarceration rates (see Figure 2-16). Because most of those who go to prison do so for the first time before age 30 to 35, these cumulative proportions can be interpreted roughly as lifetime risks of going to prison. Education, for these cumulative risks, is recorded in three categories: for those who attended at least some college, for high school graduates or GED earners, and for those who did not complete high school.

Similar to the increases in incarceration rates, cumulative risks of imprisonment have increased substantially for all men with no college education and to extraordinary absolute levels for men who did not complete high school. The prison system was not a prominent presence in the lives of white men born just after World War II. Among high school dropouts, only 4% had been to prison by their mid-30s. The lifetime risk of imprisonment was about the same for Hispanic high school dropouts at that time. For African American men who dropped out of high school and reached their mid-30s at the end of the 1970s, the lifetime risk of imprisonment was about 3 times higher, at 15%.

The younger cohort growing up through the prison boom and reaching their mid-30s in 2009 faced a significantly elevated risk of imprisonment. Similar to the rise in incarceration rates, most of the growth in lifetime risk of imprisonment was concentrated among men who had not been to college. Imprisonment risk reached extraordinary levels among high school dropouts. Among recent cohorts of African American men, 68% of those who dropped out of school served time in state or federal prison. For these men with very little schooling, serving time in state or federal prison had become a normal life event. Although imprisonment was less pervasive among low-educated whites and Hispanic men, the figures are still striking. Among recent cohorts of male dropouts, 28% of whites and 20% of Hispanics had a prison record by the peak of the prison boom.

In sum, trends in these disaggregated rates of incarceration show that not only did incarceration climb to historically high levels, but also its growth was concentrated among prime-age men with little schooling, particularly low-educated black and Hispanic men. For this segment of the population, acutely disadvantaged to begin with, serving time in prison had become commonplace.

CONCLUSION

After a lengthy period of stability in incarceration rates, the penal system began a sustained period of growth beginning in 1973 and continuing for the next 40 years. U.S. incarceration rates are historically high, and currently are the highest in the world. Clues to the causes and consequences of these high rates lie in their community and demographic distribution. The characteristics of the penal population—age, schooling, race/ethnicity—indicate a disadvantaged population that not only is involved in crime but also has few economic opportunities and faces significant obstacles to social mobility. Through its secondary contact with families and poor communities, the penal system has effects that extend far beyond those who are incarcerated

The review of the evidence in this chapter points to four key findings: 1. Current incarceration rates are historically and comparatively unprecedented. The United States has the highest incarceration rates in the world, reaching extraordinary absolute levels in the most recent two decades. 2. The growth in imprisonment—most rapid in the 1980s, then slower in the 1990s and 2000s—is attributable largely to increases in prison admission rates and time served. Increased admission rates are closely associated with increased incarceration for drug crimes and explain much of the growth of incarceration in the 1980s, while increased time served is closely associated with incarceration for violent crimes and explains much of the growth since the 1980s. These trends are, in turn, attributable largely to changes in sentencing policy over the period, as detailed in Chapter 3. Rising rates of incarceration for major offenses are not associated with trends in crime. 3. The growth in incarceration rates in the 1970s and 1980s was associated with high and increasing black-white disparities that subsequently declined in the 1990s and 2000s. Yet despite the decline in racial disparity, the black-white ratio of incarceration rates remained very high (greater than 4 to 1) by 2010. 4. Racial and ethnic disparities have combined with sex, age, and education stratification to produce extremely high rates of incarceration among recent cohorts of young African American men with no college education. Among recent cohorts of black men, about one in five who have never been to college and well over half of all high school dropouts have served time in state or federal prison at some point in their lives.

CHAPTER 3 Policies and Practices Contributing to High Rates of Incarceration

High rates of incarceration in the United States and the great numbers of people held in U.S. prisons and jails result substantially from decisions by policy makers to increase the use and severity of prison sentences. At various times, other factors have contributed as well. These include rising crime rates in the 1970s and 1980s; decisions by police officials to emphasize street-level arrests of drug dealers in the “war on drugs”; and changes in prevailing attitudes toward crime and criminals that led prosecutors, judges, and parole and other correctional officials to deal more harshly with individuals convicted of crimes. The increase in U.S. incarceration rates over the past 40 years is preponderantly the result of increases both in the likelihood of imprisonment and in lengths of prison sentences—with the latter having been the primary cause since 1990. These increases, in turn, are a product of the proliferation in nearly every state and in the federal system of laws and guidelines providing for lengthy prison sentences for drug and violent crimes and repeat offenses, and the enactment in more than half the states and in the federal system of three strikes and truth-in-sentencing laws.

The increase in the use of imprisonment as a response to crime reflects a clear policy choice. In the 1980s and 1990s, state and federal legislators passed and governors and presidents signed laws intended to ensure that more of those convicted would be imprisoned and that prison terms for many offenses would be longer than in earlier periods. No other inference can be drawn from the enactment of hundreds of laws mandating lengthier prison terms. In the federal Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement

Act of 1994, for example, a state applying for a federal grant for prison construction was required to show that it: (A) has increased the percentage of convicted violent offenders sentenced to prison; (B) has increased the average prison time which will be served in prison by convicted violent offenders sentenced to prison; (C) has increased the percentage of sentence which will be served in prison by violent offenders sentenced to prison.

American sentencing policies, practices, and patterns have changed dramatically during the past 40 years. In 1972, the incarceration rate had been falling since 1961

The federal system and every U.S. state had an “indeterminate sentencing” system premised on ideas about the need to individualize sentences in each case and on rehabilitation as the primary aim of punishment. Indeterminate sentencing had been ubiquitous in the United States since the 1930s. Statutes defined crimes and set out broad ranges of authorized sentences. Judges had discretion to decide whether to impose prison, jail, probation, or monetary sentences.

Sentence appeals were for all practical purposes unavailable. Because sentencing was to be individualized and judges had wide discretion, there were no standards for appellate judges to use in assessing a challenged sentence. For the prison-bound, judges set maximum (and sometimes minimum) sentences, and parole boards decided whom to release and when. Prison systems had extensive procedures for time off for good behavior.