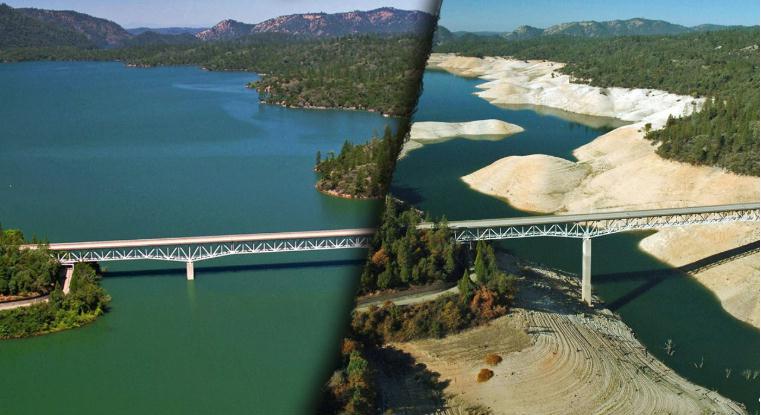

Preface. Climate change will impact California agriculture without the snow melt that allows for up to three crops to be grown a year, perhaps just one crop in the future. Not to mention the impact on the 40 million people living in California.

As far as a renewable future, hydropower is one of the only dispatchable forms of power besides natural gas, but there’ll be far less water behind dams to balance intermittent wind and solar, or provide power when neither is available. In California, it is the largest source of renewable electric power. Though as it is, it is often unavailable due to drought, low reservoirs, held back for agriculture and drinking water, for fisheries, river ecosystems and more.

Alice Friedemann www.energyskeptic.com author of “Life After Fossil Fuels: A Reality Check on Alternative Energy”, 2021, Springer; “When Trucks Stop Running: Energy and the Future of Transportation”, 2015, Springer, Barriers to Making Algal Biofuels, and “Crunch! Whole Grain Artisan Chips and Crackers”. Podcasts: Collapse Chronicles, Derrick Jensen, Practical Prepping, KunstlerCast 253, KunstlerCast278, Peak Prosperity , XX2 report

***

Siirila-Woodburn ER et al (2021) A low-to-no snow future and its impacts on water resources in the western United States. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment

This research analyzed previous climate projections and found that if greenhouse gas emissions continued along the high-emissions scenario, low-to-no-snow winters will become a regular occurrence in the western U.S. in 35 to 60 years. There has been a 21% decline in the April 1 snowpack water storage in the western U.S. since the 1950s – that’s equivalent to Lake Mead’s storage capacity, so around mid-century we should expect a comparable decline in snowpack, and by the end of the century, the decline could reach more than 50%.

Bane B (2020) Error correction means California’s future wetter winters may never come. Phys.org

California and other areas of the U.S. Southwest may see less future winter precipitation than previously projected by climate models. After probing a persistent error in widely used models, researchers at the Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory estimate that California will likely experience drier winters in the future than projected by some climate models, meaning residents may see less spring runoff, higher spring temperatures, and an increased risk of wildfire in coming years.

CEC (2014) Climate change impacts on generation of wind, solar, and hydropower in California. California Energy Commission

Excerpts:

The study findings for hydroelectric power generation show significant reductions that are a consequence of the large predicted reduction in annual mean precipitation in the global climate models used. Reduced precipitation and resulting reductions in runoff result in reduced hydropower generation in all months and elevation bands. These results indicate that a future that is both drier and warmer would have important impacts on the ability to generate electricity from hydropower.

Increased production of electricity from renewables, although desirable from environmental and other viewpoints, may create difficulties in consistently meeting demand for electricity and may complicate the job of operating the state’s transmission system. This would be true of any major change in electrical supply portfolio but is especially so when the proportion of weather-dependent renewables- which are subject to uncontrolled fluctuations-is increased.

Climate change may affect the ability to generate needed amounts of electricity from weather-dependent renewable resources. This could compromise California’s ability to meet renewable targets. For example, it is well documented that climate change is affecting the seasonal timing of river flows such that less hydropower is generated during months of peak demand and maximum electricity value. Generating solar and wind power may also be impacted by long-term changes in climate.

A changing climate may bring increases or decreases in mean wind speeds, as well as greater or lesser variation wind speeds. These changes could make long- term planning for wind energy purposes problematic. Some regions where continued wind development is occurring, such as California and the Great Plains, may be especially susceptible to climate change because the wind regimes of these regions are dominated by one particular atmospheric circulation pattern.

CHAPTER 4: Hydropower

Numerous modeling studies, starting with Gleick (1987), have predicted that anthropogenic climate change will have significant impacts on the natural hydrology of California, with implications for water scarcity, flood risk, and hydropower generation. The best-known of these impacts are straightforward consequences of increased temperatures: a reduced fraction of precipitation falling as snow, reduced snow extent and snow-water equivalent, and earlier melting of snow. An increased fraction of precipitation as rain in turn result s in increased wintertime runoff and river flow; earlier and reduced snow melt results in reduced late-season runoff and river flow. Despite the well-known lack of consensus among global climate models about future changes in annual California precipitation amounts, the effects just mentioned are robustly predicted because they result from warming, about which there is consensus. Confidence in these predictions is increased by observational studies that show these changes to be underway as well as by studies involving both observations and modeling that indicate that observed changes in western U.S. hydrology are too rapid to be explained entirely by natural causes.

One possible consequence of human-caused changes in mountain hydrology in the western United States is changes in hydropower production, especially from high-altitude facilities on watersheds that have historically been snow-dominated. This concern is especially acute, since a majority of the state’s hydropower is produced in facilities of this type. Furthermore, these high-elevation facilities have relatively little storage capacity, implying limited capability to adapt to changes in climate.

A shift toward earlier-in-the-year snowmelt and runoff would tend to produce similar changes in the timing of hydropower generation. In particular, in the absence of adequate storage capacity, it might become difficult to produce power at the end of the dry season, when demand for electricity can be very high.

On the other hand, a large enough reservoir could store enough water to effectively buffer this problem and allow power generation throughout the dry season. This means that the effects of climate change on hydropower generation will depend strongly on reservoir size. And of course on altitude, being greatest at intermediate altitudes where slight warming will raise the temperature above freezing. Watersheds that are already rain-dominated, or are well below freezing, will not exhibit the effects discussed here in the near future.

Of course, besides issues of seasonal timing, a significant increase or decrease in annual total precipitation would be an important benefit or detriment (respectively) to hydropower generation.

The published literature largely supports this picture.

Madani and Lund (2009) looked at hydropower generation in 137 high-elevation systems under three simple climate change scenarios: wet, dry, and warming only. It found that existing storage capacity is sufficient to largely compensate for expected changes in the seasonal timing of snowmelt, runoff, and river flow. A hypothetical decrease in annual total runoff, however, translates more directly into a corresponding reduction in energy generation. The predicted response to a hypothetical increase in annual runoff, however, is not symmetrical: this scenario results in increased spill and very little increase in energy production.

Results

The research team’s results for optimized energy generation are driven primarily by large projected reductions in precipitation in the future climate scenario. In the study area, annual mean precipitation in the future period is reduced by as much as 30 percent compared to in the historical reference period. Because of the complex relationships among precipitation, evapotranspiration, and runoff, these already- large precipitation decreases produce proportionately larger reductions in run off and stream flow. In other words, the percentage reductions in runoff and river flow exceed those in precipitation.

This phenomenon is exaggerated by the tendency for warming to result in increased evaporation.

Disproportionate decreases in runoff in a dry future- climate scenario are seen in other modeling studies Jones et al. (2005) investigated changes in runoff in several surface hydrology models in response to a hypothetical 1% change in precipitation and found responses ranging from 1.8 to 4.1%; that is, the percentage response in runoff was anywhere from roughly double to roughly 4x the percentage change in precipitation.

Reduced precipitation and resulting reductions in runoff result in reduced hydropower generation in all months and elevation bands

These results indicate that a future that is both drier and warmer would have important impacts on the ability to generate electricity from hydropower.

2 Responses to Climate change effects on hydropower in California