Preface. Copper is essential for modern civilization and any hope of migrating to renewable energy, since solar, wind, tidal, hydro, biomass and geothermal use 5 times more copper than traditional power generation in fossil and nuclear power plants. Nothing matches copper for electric wiring, which is used in power generation, power transmission & distribution, telecommunications, vehicles, cookware,and hundreds of kinds of electrical equipment. It’s used on integrated circuits, printed circuit boards, vacuum tubes, magnetrons in microwave ovens, electric motors. Copper is used in buildings for its corrosion resistance in roofs, flashings, gutters, and so on. It’s used in ships to protect against barnacles and mussels, and aquaculture and health care due to its antimicrobial, corrosion-resistance, and prevention of biofouling. Wikipedia Copper has even more uses.

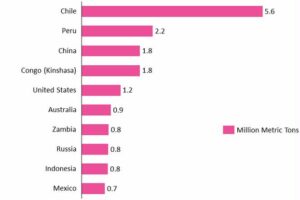

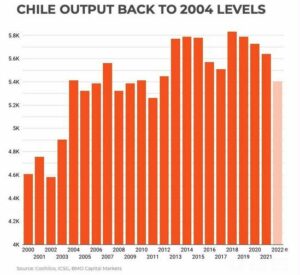

As you can see in Figure 1, Chile produced the most copper of any nation — a quarter of all copper in 2021. Figure 2 shows that in 2022, Chilean production dropped to 2004 levels due to water scarcity, declining grades of ore, depletion rates, tax increases, regulatory uncertainty and other factors.

Figure 1. Largest copper producing countries 2021 (million metric tons). Source: www.usgs.gov

Figure 2. Chile copper production 2000-2022

Elon Musk told a closed-door Washington conference of miners, regulators and lawmakers that he sees a shortage of EV minerals coming, including copper and nickel (Scheyder 2019). In 2024, Scheyder wrote a fantastic book about mining. A must read book to understand the impact mining will have on the planet and all about how mining works, the energy involved and more — quite interesting. Basically for climate change, we are crossing many of the other 8 existential boundaries and destroying the earth in arguably worse ways, and it is not clear to me at all that mining and renewables affects climate change one bit, you will see in Sheyder’s book (reviewed below) what a tremendous amount of fossils are used in mining, and recycling, which is also mining but barely happening for most metals.

Learn more about copper and other mineral shortages here: Michaux S (2021) The Mining of minerals and the Limits to growth. Geological Survey of Finland.

Alice Friedemann www.energyskeptic.com Author of Life After Fossil Fuels: A Reality Check on Alternative Energy; When Trucks Stop Running: Energy and the Future of Transportation”, Barriers to Making Algal Biofuels, & “Crunch! Whole Grain Artisan Chips and Crackers”. Women in ecology Podcasts: WGBH, Jore, Planet: Critical, Crazy Town, Collapse Chronicles, Derrick Jensen, Practical Prepping, Kunstler 253 &278, Peak Prosperity, Index of best energyskeptic posts

***

Scheyder E (2024) The War Below: Lithium, Copper, and the Global Battle to Power Our Lives. Atria.

Battery 4 main parts: an anode, cathode, electrolyte, and separator. An anode is typically made with graphite. A cathode is made with lithium and, depending on design, a mix of nickel, manganese, cobalt, or aluminum. Between the two is an electrolyte solution often made of lithium, with a separator composed of plastic in between. Inside an EV’s motor sits more than a mile of copper wiring that is used to help turn power from the battery into motion.

The bigger the battery, the more metals needed. The Model 3 uses 0.11 kilograms (kg)/2.2 lbs of lithium for every kWh. So Tesla’s 55.4 kWh battery was built with 6 kg of lithium, 42 kg of nickel, nearly 8 kg of cobalt, 8 kg of aluminum, nearly 55 kg of graphite, and about 17 kg of copper, with even more aluminum and copper elsewhere in the battery.

China has some lithium reserves locked in hard-to-extract deposits. China is the world’s largest copper consumer and aggressively buys the red metal, a major conductor of electricity, from Chile, Peru, and other nations. U.S. copper production dropped nearly 5 percent from 2017 through 2021.

No new mines for any of these metals have opened in the United States for decades, with the exception of a small Nevada copper facility in 2019. Yet multiple projects have been proposed that could produce enough copper to build more than 6 million EVs, enough lithium to build more than 2 million EVs, and enough nickel to build more than 60,000 EVs.

The United States wants to go green, but to do that, it will need to produce more metals, especially lithium, rare earths, and copper. That means more mines. And mines are very controversial in the United States. Who wants to live next to a giant hole in the ground? Mines are dusty, increase truck traffic, and use dynamite for blasting that can rattle windows and crack foundations. Many mines throughout history have polluted waterways and produced toxic waste that scarred landscapes for generations.

They also require astronomical amounts of water to operate. Stewart Udall, who ran the U.S. Interior Department under Presidents John. F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, described mining as a “search-and-destroy mission.”

The process to produce these metals can vary widely by type and is vastly different than oil and natural gas production.

China has been scouring the world the past 20 years for cobalt, lithium, copper, and other metals. After the United States pulled out of Afghanistan in 2021, Chinese mining companies began negotiating with the Taliban to develop the Mes Aynak copper deposit, about two hours outside of Kabul. China’s mining companies spent billions of dollars buying cobalt mines in the Congo. In Argentina, China has invested in six major lithium projects. As 2023 dawned, India began scouring Argentina’s reserves of copper and lithium to sate its burgeoning EV industry.

Recycling alone cannot provide the materials needed to fuel the global green energy transition.

The United States is watching its petroleum dependence on the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries transition into a dependence on China, Congo, and others for the building blocks of green energy devices. China has threatened to block exports to the United States of rare earths. The United States is expected to produce just 3 percent of the world’s annual lithium needs by 2030, even though it holds about 24% of the world’s lithium reserves.

In Brazil, a tailings dam collapsed and released a torrent of toxic sludge that quickly devastated much of the nearby countryside and killed almost 300 people. After that, Brazil’s government outlawed the type of tailings dam design that had collapsed, but the U.S. did not follow suit, fueling concern in Minnesota, Arizona, and other states that similar collapses could happen there if new mines were built. Where exactly? “We’ll be looking up at a 500-foot dam containing 1.6 billion tonnes of toxic waste and wondering when it is going to collapse and bury the community,” an Arizonan said of Rio Tinto’s plans to build a large copper mine and tailings waste storage site.

Are risks—even tragedies—such as these to be tolerated on the road to a green energy future?

Copper, one of the best electricity-conducting metals, is easy to shape and form, is corrosion-resistant, and binds well with other metals. Only silver conducts electricity better, but silver is more expensive than copper.

The average 747 jetliner from Boeing has 135 miles of copper wiring, and every American household has an average of 400 pounds of copper wiring and piping. Freeport-McMoRan’s Morenci, the largest copper mine in North America, uses Caterpillar 797 trucks to haul ore; inside each of those trucks’ radiators is at least 400 pounds of the red metal.

About 75% of the copper used throughout history has been mined since the Second World War.14 And the world’s lust for copper is set to only grow. In 2022, annual copper consumption was 25 million tonnes. By 2050, it’s projected to more than double to 53 million tonnes.

There is not expected to be enough copper to meet that 2050 target without more mines and more recycling. Without adequate copper supply in the 21st century, wars could very well be fought over copper, the consultancy S&P Global has warned. The U.S. would have to boost its copper imports from about 44% of its supply in 2022 to as much as 67% by 2035, unless it produces more of its own.

The discovery of the Resolution Copper deposit in the 1990s tested that tweak. It took more than a decade for Rio Tinto and BHP to study the deposit. They bored more than a hundred exploratory drills into the Earth, at a cost of more than $1 million each. They built the deepest mine shaft in the United States, a 7,000-foot-deep structure on a small sliver of adjoining land they controlled. They discovered that if they built the mine, it would supply a quarter of the copper consumed each year in the United States. Because the copper deposit is so deep, Rio and BHP also discovered it likely could not be extracted by digging from the surface but rather from below with a method known as block caving, whereby a large section of rock is undercut, creating an artificial cave that fills with its own rubble as it collapses under its own weight. That would cause a crater 2 miles wide and 1,000 feet deep, in what the mining industry terms a “glory hole.” (Yes, really.) Thus, to harvest the copper would require the destruction of a site considered as important to the San Carlos Apache as St. Peter’s Basilica is to Roman Catholics. The mine could use as much as 590,000 acre-feet of water over the course of its life, roughly 192 billion gallons, equal to nearly 5 gallons of water for every pound of copper, an alarming amount for a state that had been in a drought since 1994. The amount of water would be enough to supply 168,000 homes for 40 years. The mine would also produce a pile of waste rock stored behind a tailings dam that would be 500 feet tall and cover an area of 6 square miles. By 2013, Rio and BHP had started the U.S. federal permitting process, though as of this writing they have not obtained the permits. In 2004, it had taken a 55% stake in the Resolution Copper project to BHP’s 45%, giving it effective control over strategy, budget, and most important, outreach to the local communities, including Superior and the San Carlos Apache. Rio and BHP by 2021 had spent more than $2 billion on the project, without producing an ounce of copper. In its bid to win over local hearts and minds, Rio had promised to hire fourteen hundred workers—nearly half of the town’s population—with an average salary of $100,000, more than quadruple the 2020 average.

Who cares, Nosie was saying, if you have a high-paying job if the environment is destroyed? The proposed mine itself was a symptom of a way of life that cared only for money, he said. “That means everything here that is left, all water, all light, the beauty of environment, what brings people back here and then the holy and sacredness of this, is totally gone.

About 200 miles east of Phoenix sits the town of Morenci and its roughly 1,500 residents. Morenci has a copper mine that covers 100 square miles and is still growing. It is the largest mine for any metal on the North American continent, churning out 900 million pounds of copper in 2022. Every day a fleet of 154 mining trucks moves 815,000 tonnes (1.8 billion pounds) of rock, with each truck bed capable of carrying 236 tons (520,290 pounds) per load. Much of the copper at the Morenci deposit is considered low-grade, ranging somewhere between 0.23 and 0.5 percent. That means for every 100 pounds of rock those trucks move, about a quarter to half a pound is copper. A lot of rock needs to get moved, and a lot of waste rock needs to be stored somewhere. The mine also paid no royalties to the state or federal governments—just like every other Freeport-owned mine in the United States.

“The world is becoming much more electric,” Freeport-McMoRan’s chief executive, Richard Adkerson, told me. “Electricity means copper.”

After drilling and blasting Morenci’s pits, Freeport then loaded rock onto trucks and hauled it to one of two basic types of processing. One method is to crush the rock in giant tumblers that turn 24/7, mill it into a fine powder, and then lightly process it into what’s known as copper concentrate, before sending it to a nearby smelter, where the concentrate is melted and then put into molds for various products, including pipes. Another method is to pile the rock onto leach pads, where an acid concoction is applied via drip irrigation to tease out the copper, after which the acid solution—known as a Pregnant Leach Solution, containing 2 grams of copper for every liter—is collected at the bottom of the pad and processed into flat sheets of the red metal known as copper cathode by using electrical currents. A quarter of the nearly 100 square miles that compose the Morenci mine site holds tailings ponds that store the muddy detritus of the mining process.

Freeport now has a big problem: finding miners. More than half of Western miners in 2021 were over the age of 45. A fifth were over 60 and nearing retirement. The U.S. government formed a committee aimed to address this aging workforce and “public perceptions about the nature of mining.” In China in 2020, just one mining school enrolled more mining students than were enrolled in all of the United States. Adkerson and other Freeport executives visited universities, trying to convince students to change their majors to mining engineering.

But despite copper’s role in the green energy transition, few young people in the West wanted to help procure it. By 2023, when Freeport’s copper production in the United States fell not because of weak commodity prices or weather or economic tensions, but because the company did not have enough workers. And Quirk and Adkerson warned the problem would only get worse. “Our work is hard work,” Adkerson said. “It’s harder to drive a big-haul truck than it is to drive an Amazon or UPS or FedEx truck.”

Zaremba H (2022) The Energy Transition Could Be Derailed By A Looming Copper Shortage. Oilprice.com

“…a looming copper shortage threatens to completely derail the clean energy transition, and by extension, climate pledges across the world. According to a recent report from S&P Platts, if copper shortfalls follow projected trends, climate goals will be “short-circuited and remain out of reach.”

Copper is particularly effective in a wide range of low-carbon alternatives because of its relatively high electrical conductivity and low reactivity. It’s not that traditional energy production and transmission and gas-powered vehicles don’t use copper in their manufacturing – it’s just that renewables and electric vehicles require a whole lot more of it. “An EV requires 2.5 times as much copper as an internal combustion engine vehicle,” reports CNBC. “Meanwhile, solar and offshore wind need two times and five times, respectively, more copper per megawatt of installed capacity than power generated using natural gas or coal.”

S&P projects that current levels of demand will nearly double by the year 2035, climbing to a whopping 50 million metric tons. That figure will climb to more than 53 million metric tons by 2050, which amounts to “more than all the copper consumed in the world between 1900 and 2021.

Richard A. Kerr. February 14, 2014. The Coming Copper Peak. Science 343:722-724.

Production of the vital metal will top out and decline within decades, according to a new model that may hold lessons for other resources.

If you take social unrest and environmental factors into account, the peak could be as early as the 2020s

As a crude way of taking account of social and environmental constraints on production, Northey and colleagues reduced the amount of copper available for extraction in their model by 50%. Then the peak that came in the late 2030s falls to the early 2020s, just a decade away.

After peak Copper

Whenever it comes, the copper peak will bring change. Graedel and his Yale colleagues reported in a paper published on 2 December 2013 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that copper is one of four metals—chromium, manganese, and lead being the others—for which “no good substitutes are presently available for their major uses.”

If electrons are the lifeblood of a modern economy, copper makes up its blood vessels. In cables, wires, and contacts, copper is at the core of the electrical distribution system, from power stations to the internet. A small car has 20 kilograms (44 lbs) of copper in everything from its starter motor to the radiator; hybrid cars have twice that. But even in the face of exponentially rising consumption—reaching 17 million metric tons in 2012—miners have for 10,000 years met the world’s demand for copper.

But perhaps not for much longer. A group of resource specialists has taken the first shot at projecting how much more copper miners will wring from the planet. In their model runs, described this month in the journal Resources, Conservation and Recycling, production peaks by about mid-century even if copper is more abundant than most geologists believe.

Predicting when production of any natural resource will peak is fraught with uncertainty. Witness the running debate over when world oil production will peak (Science, 3 February 2012, p. 522).

The team is applying its depletion model to other mineral resources, from oil to lithium, that also face exponentially escalating demands on a depleting resource.

The world’s copper future is not as rosy as a minimum “125-year supply” might suggest, however. For one thing, any future world will have more people in it, perhaps a third more by 2050. And the hope, at least, is that a larger proportion of those people will enjoy a higher standard of living, which today means a higher consumption of copper per person. Sooner or later, world copper production will increase until demand cannot be met from much-depleted deposits. At that point, production will peak and eventually go into decline—a pattern seen in the early 1970s with U.S. oil production.

For any resource, the timing of the peak depends on a dynamic interplay of geology, economics, and technology. But resource modeler Steve Mohr of the University of Technology, Sydney (UTS), in Australia, waded in anyway. For his 2010 dissertation, he developed a mathematical model for projecting production of mineral resources, taking account of expected demand and the amount thought to be still in the ground. In concept, it is much like the Hubbert curves drawn for peak oil production, but Mohr’s model is the first to be applied to other mineral resources without the assumption that supplies are unlimited.

Exponential growth

Increasing the amount of accessible copper by 50% to account for what might yet be discovered moves the production peak back only a few years, to about 2045 — even doubling the copper pushes peak production back only to about 2050. Quadrupling only delays peak until 2075.

Copper trouble spots

The world has been so thoroughly explored for copper that most of the big deposits have probably already been found. Although there will be plenty of discoveries, they will likely be on the small side.

“The critical issues constraining the copper industry are social, environmental, and economic,” Mudd writes in an e-mail. Any process intended to extract a kilogram of metal locked in a ton of rock buried hundreds of meters down inevitably raises issues of energy and water consumption, pollution, and local community concerns.

Civil war and instability make many large copper deposits unavailable

Mudd has a long list of copper mining trouble spots. The Reko Diq deposit in northwestern Pakistan close to both Iran and Afghanistan holds $232 billion of copper, but it is tantalizingly out of reach, with security problems and conflicts between local government and mining companies continuing to prevent development. The big Panguna mine in Bougainville, Papua New Guinea, has been closed for 25 years, ever since its social and environmental effects sparked a 10-year civil war that left about 20,000 dead.

Are we about to destroy the largest salmon fishery in the world for copper?

On 15 January the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency issued a study of the potential effects of the yet-to-be-proposed Pebble Mine on Bristol Bay in southwestern Alaska. Environmental groups had already targeted the project, and the study gives them plenty of new ammunition, finding that it would destroy as much as 150 kilometers of salmon-supporting streams and wipe out more than 2000 hectares of wetlands, ponds, and lakes.

Gold and Oil have already peaked

Copper is far from the only mineral resource in a race between depletion—which pushes up costs—and new technology, which can increase supply and push costs down. Gold production has been flat for the past decade despite a soaring price (Science, 2 March 2012, p. 1038). Much crystal ball–gazing has considered the fate of world oil production. “Peakists” think the world may be at or near the peak now, pointing to the long run of $100-a-barrel oil as evidence that the squeeze is already on.

Coal likely to peak in 2034, all fossil fuels by 2030, according to Mohr’s model

Fridley, Heinberg, Patzek, and other scientists believe Peak Coal is already here or likely by 2020.

Coal will begin to falter soon after, his model suggests, with production most likely peaking in 2034. The production of all fossil fuels, the bottom line of his dissertation, will peak by 2030, according to Mohr’s best estimate. Only lithium, the essential element of electric and hybrid vehicle batteries, looks to offer a sufficient supply through this century. So keep an eye on oil and gold the next few years; copper may peak close behind.

References

Gorman, S. August 30, 2009. As hybrid cars gobble rare metals, shortage looms. Reuters.

Scheyder, E. 2019. Exclusive: Tesla expects global shortage of electric vehicle battery minerals. Reuters.

3 Responses to Peak Copper