Preface. On top of aquifer depletion, water shortages in California are also expected in the future as rainfall and snowfall decline and snow melts earlier.

Over half of Americans rely on underground aquifers for drinking water (Glennon 2002). Seventy percent of our groundwater is used to grow irrigated crops. The rest is used by livestock, aquaculture, industry, mining, and thermoelectric power plants (USGS 2018).

Two of the most important aquifers in the U.S. are the multiple aquifers beneath the Central Valley in California, and the Ogallala beneath the Great Plains. Both are in arid regions, but they are also the nation’s breadbaskets. More than half of America’s food is grown in these two regions.

Aquifers in California provide a third of the state’s water.

At the rate farmers are depleting California aquifers, which lie beneath the best soil in the nation, this region could run out of groundwater as early as the 2030s (de Graaf et al. 2015). Poof, a big bite of U.S. food disappears from our plates. From 2000-2008, California used up a fifth of all the aquifer water that had ever existed there (Konikow 2013), and even more during the great drought of 2011 to 2017.

When too much groundwater is withdrawn, the ground can literally sink beneath us. Irreversible compaction can occur, causing permanent subsidence and loss of storage capacity. Subsidence also breaks roads, pipelines, and canals.

When too much water is pumped from aquifers, rivers and lakes can dry up. Saltwater may intrude, rendering water undrinkable. This problem is quite serious in California as well as Florida, Texas, and South Carolina (Glennon 2002).

California grows a large percentage of the food in the nation — almost half of all fruits, nuts, and vegetables and a whopping share of livestock and dairy as well. There are 66 food crops produced in California more than any other state, including nearly all of the almonds, artichokes, dates, figs, raisins, kiwi, olives, peaches, pistachios, prunes, pomegranates, sweet rice and walnuts.

Crops require a mind-boggling amount of water. It takes 13,676 liters (3613 gallons) of rainfall or irrigation water to produce enough soybeans to make just one liter (0.25 gallon) of biodiesel. Corn is more efficient, though still a heavy drinker, using 2,570 liters (680 gallons) of water per liter of ethanol produced (Gerbens-Leenes et al. 2009).

Although most Californians are under the impression that fruit and nut crops use the most water, the crop types with the greatest rates of aquifer subsidence and groundwater use are field crops like corn and soy, followed by pasture crops like alfalfa, truck crops like tomatoes, and lastly, fruit and nut crops like almonds and grapes (Levy et al 2020).

2016-9-27 California’s almond boom has ramped up water use, consumed wetlands and stressed pollinators. Geological Society of America. Land converted to grow almonds (16,000 acres were wetlands) between 2007 & 2014 has led to a 27% annual increase in irrigation demand despite the worst drought in over a millennia

Alice Friedemann www.energyskeptic.com author of “Life After Fossil Fuels: A Reality Check on Alternative Energy”, 2021, Springer; “When Trucks Stop Running: Energy and the Future of Transportation”, 2015, Springer, Barriers to Making Algal Biofuels, and “Crunch! Whole Grain Artisan Chips and Crackers”. Podcasts: Collapse Chronicles, Derrick Jensen, Practical Prepping, KunstlerCast 253, KunstlerCast278, Peak Prosperity , XX2 report

***

Gasparini A (2021) Scientists worry that California’s ‘fossil water’ is vanishing. Mercury News.

California has ancient aquifers created by rain and snow over 10,000 years ago. Research on fossil water from Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory suggests that managers of drinking wells that pump fossil water can’t rely on it being replenished — especially during times of drought. This water wont be replenished for hundreds or even thousands of years.

The study found clear evidence that 7% of the 2,330 California’s drinking wells tested are producing fossil water — and 22% of those wells are pumping mixed-age water containing at least some ancient water. That means that many Californians are already using fossil water to shower, flush their toilets and irrigate their lawns without knowing it.

Excessive agricultural and urban water use has depleted many of California’s aquifers, which serve as massive underground reservoirs. In some areas, the problem is so severe that the land is sinking — permanently in some cases.

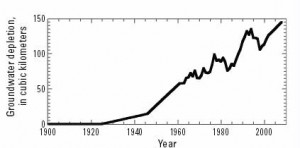

Konikow, L.F., 2013, Groundwater depletion in the United States (1900−2008): U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2013−5079, 63 pages.

Cumulative groundwater depletion in the Central Valley of California, 20,000 square miles, 1900 through 2008

Cumulative groundwater depletion in the Central Valley of California, 20,000 square miles, 1900 through 2008

California lost nearly 145 cubic kilometers of groundwater since 1880, with a fifth of that water disappearing in just 9 years from 2000 to 2008 (31.4 km3).

In parts of the San Joaquin Valley and Tulare Basin, water levels had declined nearly 400 feet, depleting groundwater from storage and lowering water levels to as much as 100 feet below sea level. Long-term water-level records in some wells indicate that water levels were already declining at substantial rates when water levels were first observed as early as the 1930s. The extensive groundwater pumping caused changes to the groundwater flow system, changes in water levels, changes in aquifer storage, and widespread land subsidence in the San Joaquin Valley, which began in the 1920s.

The thickness of sediments comprising the freshwater parts of the aquifer averages about 3000 feet in the San Joaquin Valley and 1500 feet in the Sacramento Valley. The shallow part of the aquifer system is unconfined, whereas the deeper part is semi-confined or confined.

References

de Graaf IEM, van Beek LPH, Sutanudjaja EH, et al (2015), Limits to global groundwater consumption, AGU Fall Meeting, San Francisco, California, oral presentation. https://news.agu.org/press-release/agu-fall-meeting-groundwater-resources-around-the-world-could-be-depleted-by-2050s/.

Gerbens-Leenes W, Hoekstra AY, van der Meer TH (2009) The water footprint of bioenergy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106: 10219-10223.

Glennon R (2002) Water Follies. Groundwater Pumping and the Fate of America’s Fresh Waters. Island Press.

Henry L (2019) Groundwater. A firehose of paperwork is pointed at state water officials. SJV water. https://sjvwater.org/a-firehose-of-paperwork-is-pointed-at-state-water-officials/.

Konikow LF (2013) Groundwater depletion in the United States (1900-2008): Scientific Investigations Report 2013-U.S. Geological Survey. https://doi.org/10.3133/sir20135079

Levy MC, Neely WR, Borsa AA et al (2020) Fine-scale spatiotemporal variation in subsidence across California’s San Joaquin Valley explained by groundwater demand. Environmental Research Letters 16.

USGS (2018) Estimated use of water in the U.S. in 2015. Table 4A. U.S. Geological Survey.