Preface. This is a book review of Newman’s 2022 “Things are never so bad that they can’t get worse”. He lived in Venezuela from 2012 to 2016 as a correspondent for The New York Times. Venezuela and Canada have the largest remaining oil deposits in the world. But they are resources, with only 10% or so obtainable at today’s price and technology (reserves), with the other 90% unobtainable.

But given that peak oil was likely in 2018, any country with oil will be of tremendous interest since we are utterly dependent on it for civilization as we know it.

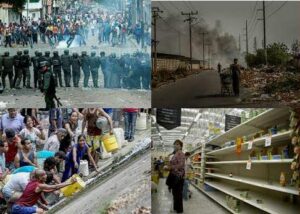

Newman might say Venezuela hasn’t collapsed yet. The lights are on in the wealthiest parts of Caracas, Maduro is still in power, and there is money to be made from gold and other resources. It’s hard to define collapse. Does some percent of the population need to die or flee? When I read what the average person is going through, it sure seems like collapse to me — one meal a day of rice or lentils for most, little to no access to health care, and preyed on by gangs and death squads. Hell on earth. Our fate some day when energy decline strikes the U.S. and meanwhile we can see how Europe copes this winter.

Newman writes that from 2013 through 2019, nearly two-thirds of all economic activity disappeared. So picture 2 out of 3 shops closed, 2 out of 3 workers unemployed, and one meal a day instead of three, often just pasta or lentils. Today in 2022, Venezuela has yet to hit bottom, despite 6 million refugees fleeing the country (of 30 million), about as many as have fled Syria and Ukraine. T

It’s hard to imagine how Venezuela could get worse after you read his book, but since there are still people making money off the status quo, mafias fighting over the tiny pieces of the remaining pie, and high levels of corruption persist, Venezuela hasn’t hit bottom yet. The central government is made up of competing circles of power. At times some factions work together against other factions, but always for their own survival. That’s why when the electric grid crashed fixing it was not the highest priority, the division of the spoils comes first. In 2022 Newman writes, Venezuela is still a giant piñata for those in a position to swing a stick at it.

I was constantly reminded of Trump. For example, Chavez was on television almost every day. From 1999 through 2012 he took over the airwaves 2,377 times to taunt and skewer opponents, delight supporters and infuriate enemies, making his fans love him even more. On one show he fired essential employees who worked for oil company PDVSA, reading off a long list of names. When he was done, Chávez picked up a whistle and blew a sharp blast. Offsides!” he said. “Get out!” Chávez’s fans loved it. They cheered. They clapped. Did you see what he did? He fired them on TV! He fired them with a whistle! He showed those elite sons of bitches who’s boss.

Chavez and Maduro hired many generals to positions they knew nothing about but for which there was a great deal of graft, weakening the oil, electric grid, and other institutions. This made them less likely to instigate a coup as well. So I have to wonder why Trump appointed four generals, more than anyone since Was he already anticipating a coup in 2016 and wanted to make sure the military would support him?

Alice Friedemann www.energyskeptic.com Author of Life After Fossil Fuels: A Reality Check on Alternative Energy; When Trucks Stop Running: Energy and the Future of Transportation”, Barriers to Making Algal Biofuels, & “Crunch! Whole Grain Artisan Chips and Crackers”. Women in ecology Podcasts: WGBH, Jore, Planet: Critical, Crazy Town, Collapse Chronicles, Derrick Jensen, Practical Prepping, Kunstler 253 &278, Peak Prosperity, Index of best energyskeptic posts

***

American policy during the Trump regime

American policy toward Venezuela and Cuba became intertwined. Cuba hard-liners believed that Venezuela had saved the Castro regime by offering it a lifeline of cheap oil. So the Cuban American lobby believed that if it could force a change of government in Venezuela, Cuba’s source of oil would dry up and Cuba and Nicaragua would fail too. The U.S. began taking actions to do that despite greatly harming the well-being of Venezuelans. And contributed to the 5.4 million of 30 million Venezuelans who fled.

Meawhile, Venezuela as buying weapons from Russia and given Russia generous and lucrative participation in its oil fields.

The only country with more refugees than Venezuela is Syria, a nation failing from both severe drought and civil war. The thread that linked both countries was Russia, which backed Venezuelan President Maduro and Syrian president Bashar al-Assad, bombing rebel areas in Syria’s civil war and catalyzing the Syrian refugee crisis. The flood of Syrian refugees into Europe heightened political stress there and energized the right-wing nationalist parties friendly to Russia. Likewise, millions of Venezuelan refugees destabilized neighboring countries and increased nationalism in Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Panama, Peru, and other countries.

So I can’t help but wonder if Russia doesn’t intend to further increase right-wing populism in Europe by forcing millions of Ukrainians to flee.

Sanctions also had a political dimension. Maduro had been saying for years that the country was under attack in an economic war waged by the United States. Playing the victim was always a Chavista fallback—the nation’s woes were always someone else’s fault. After 20 years in government, Chavismo still tried to pretend that it was the valiant outsider fighting the evil establishment. In this case, it was also a way of deflecting responsibility for bad economic policy. And it was a fantasy—until Trump made it a reality. What are sanctions if not economic warfare? Every day, on television, radio, social media, the government hammered away at the message: Venezuela was the victim of an economic war by the United States. And who are they putting the sanctions on? The people. Because the big shots, Maduro and Guaidó, they’ve got food to eat. So who do the sanctions hurt? The people.

Through negligence, corruption, and mismanagement, the Maduro government presided over the destruction of the oil industry. The Trump administration’s sanctions were the coup de grace.

Today Venezuela is a Republican Dream

Newman explains why Venezuela in 2019 fulfills the Republican dream: “Some call Venezuela a failed state. Others call it a mafia state. But it is neither. It is a state reduced to the absolute minimum. Maduro had started the process, and the Trump White House had helped him carry it to perfection. In the United States the Republican dream was to starve the beast, to cut government financing so deeply that most of the things that we expect a government to do become impossible. Then theoretically society and private initiative can flourish, unencumbered. This was Venezuela. There were almost no services, no fire trucks, no ambulances. Public hospitals and clinics barely functioned. People were on their own, left to fend for themselves, free to exercise personal responsibility.

The irony was that Republicans in the United States considered Maduro their enemy. They should have been applauding him. He was a fellow traveler.”

Venezuela in the news:

Reuters (2022) Cuba is struggling to cover a fuel deficit as imports from Venezuela and other countries decline and global prices boosted by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine make purchases almost unaffordable. Cuba is dependent on fuel imports from Venezuela to cover 75% of its demand, shortages have led to long lines at gas stations. And aging thermoelectric plants are failing more often as well. https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/cuba-struggles-buy-fuel-imports-venezuela-dwindle-data-2022-04-05/?mc_cid=7860bc0677&mc_eid=20e9bfe034

Stone R (2022) Healing Venezuela. Science 375: 1082-1085. Malaria cases rose 20-fold from 2001 to 2017. Hugo Chavez disdained science and railed against intellectuals. After Maduro took power in 2013 economic collapse soon followed and there’s been a brain drain as scientists fled. Those stuck in Venezuela have seen their labs stripped of anything of value. Criminals pillaged the Institute of Tropical Medicine over 20 times in 2016 alone. Now Venezuelans are in survival mode with most lacking access to water and sanitation, medicine is scarce, and in 2014 the government shut down all medical data collection, so the true scope of this ongoing disaster isn’t known fully. What little medical care exists is private near elite clientele who still have electricity and clean water. A September 2021 survey found 77% of Venezuelans are living in extreme poverty. High prices allow most families to buy only a few days’ of food every month.

Alice Friedemann www.energyskeptic.com Author of Life After Fossil Fuels: A Reality Check on Alternative Energy; When Trucks Stop Running: Energy and the Future of Transportation”, Barriers to Making Algal Biofuels, & “Crunch! Whole Grain Artisan Chips and Crackers”. Women in ecology Podcasts: WGBH, Jore, Planet: Critical, Crazy Town, Collapse Chronicles, Derrick Jensen, Practical Prepping, Kunstler 253 &278, Peak Prosperity, Index of best energyskeptic posts

***

Newman W (2022) Things Are Never So Bad That They Can’t Get Worse. St. Martin’s Press.

Venezuela’s first oil well was drilled near Lake Maracaibo, in the far western state of Zulia in 1914 and is still pumping oil in 2014. The first oil workers’ strike occurred here (and was put down here) in 1925. In 1976, during the country’s first petro-delirium, when oil prices quadrupled, President Carlos Andrés Pérez came to Mene Grande to declare the nationalization of the oil industry. Three decades later, in the midst of an even bigger boom, President Hugo Chávez came here to announce a second nationalization, changing the terms by which foreign oil companies operated in Venezuela and giving the government a controlling stake in everything that happened in the oil fields. The word mene, in the name of the town Mene Grande, comes from an indigenous word for oil seep, a place where oil bubbles up naturally from the earth. That is typical of Venezuela’s oil.

The oil surges up, and over time it congeals and becomes a mound of something like tar or asphalt. Behind the tricolor park with the first oil well was a barrio, tumbling down the back of the hill, where people lived in hovels. Wandering around the barrio, I came upon a woman who was probably in her thirties or forties, but she looked twice that age. Her bones showed under the skin of her arms. She wore a housedress so threadbare that it was almost sheer, and whatever color it once had was gone. She seemed faded too in the white-hot sun, bleached instead of burnt or tanned. She lived in one of the worst hovels I’d seen in Venezuela or anywhere else, a teetering collection of corrugated metal, cardboard, and wood. The most striking thing of all was that it had been assembled on top of a mene. Shiny slicks of oil stained the earth all around. To keep themselves out of the muck, the woman and her family had built up a kind of midden, maybe three feet high, from chunks of hardened oil residue and debris. It was like a big, broad pitcher’s mound with a shack on top. Using a rectangular metal can for a stool, she sat in front of her hovel, on top of this mound of oil in its various states of coagulation,

before the crisis, before the collapse, before hyperinflation, before the bottom dropped out from under the price of oil, there would have been three or four operators watching the computer screens in the central control room in Caracas that monitored the electrical grid for all of Venezuela. In March 2019 there was just one man in Venezuela in charge of making sure that there was a smooth flow of electricity to every city and town and millions of homes and businesses, with their air conditioners, refrigerators, televisions, and appliances, and all the airports and seaports, government offices, oil wells, refineries, and everything else in the country that used electrical power.

Venezuela has one national control room because the country is composed of a single integrated power grid. About three-quarters of Venezuela’s electrical generating capacity resides in three large hydroelectric plants in the far eastern part of the country, in what is known as the Guayana sector. Those generating plants provide virtually all the power used in Caracas and a large portion of the electricity used in Maracaibo, Venezuela’s second- largest city, all the way across the country, close to the western border with Colombia.

He’d watched his coworkers disappear. Your salary wasn’t enough even to buy food for your family. Some drifted off to find other work in Caracas. Others had taken jobs with electrical utilities in Chile or Colombia or Ecuador. But Darwin and a few colleagues had stayed. No one wanted to leave Venezuela. Your people were here—your family, your parents, your friends. It was the life you knew.

On any given day, all sorts of things could happen—a brush fire under a transmission line could cause a spike in current, a transformer could blow—and then you had to think and act fast. And if it occurred at peak consumption, you had to scramble to keep power flowing. It was like being the pilot of a jet plane when an engine goes out in flight. You had alarms going off and split-second decisions to make. These days the whole system was under strain, held together with chewing gum. Equipment was going longer without being replaced; less maintenance was being done.

On March 7, 2019, Darwin was less than halfway through his 24-four-hour shift when a series of alarms flashed on the screens in front of him. Power had gone out all across the country. From one moment to the next, as though someone had thrown a switch, all of Venezuela had no electricity. In some places it would stay out for five days. Millions of people would run short of food and water. Hospital operating rooms went dark. Banks and grocery stores couldn’t function. In a few days the looting would start. Two weeks later the lights would go out again. And then again less than a week after that. And again in early April. The system was falling apart.

Night had fallen, and the valley of Caracas lay before him, plunged in blackness. There was no twinkle of a thousand bare lightbulbs in the shantytowns climbing the hillsides, no lights from the giant housing blocks, no yellow glow from the wealthy enclaves to the south, no lights in the middle-class neighborhood that spread out below his window, no tangerine-tinged streetlamps. There was only darkness. The headlights of cars slashed white channels through the night, but that only seemed to accentuate the blackness all around.

In 1989, I was living in Mexico City, and I watched on television as Caracas was swept by riots and looting. Police and soldiers opened fire on the looters and hundreds of people were killed. My Mexican friends were stunned. For them, Venezuela was a place apart, a country touched by the blessing of wealth. Mexico had oil too, but nothing like Venezuela. La Venezuela Saudita, people called it: a Latin American Saudi Arabia. The chaos on television belied all that. It was like the crushing of a dream. The riots exposed Venezuela as a hollow fantasy—a pretty bauble on the outside, with rolls of money and shopping trips abroad, while inside, there was pulverizing poverty, a familiar tale of debt, mismanagement, pauperism, and corruption.

By the time I moved to Venezuela, as a foreign correspondent, in January 2012, the country was deeply divided. You could say that division is what defined it. Pro-Chávez versus anti-Chávez. Poor versus well-off. Red T-shirt versus any other color T-shirt. You were for or against. On one side or the other. The division was obvious everywhere I went and in nearly every conversation

People were talking across one another, over one another; they were full of anger and incomprehension; they’d given up trying to understand one another. They were frustrated and pissed off, and when they talked about it, the words often came out at top volume. The causes of the division were historical, but the rift deepened with Chávez. He had mined it and encouraged it until it became part of the landscape, something that people took as a given.

Each of them was shouting so loud, and with so much intensity, that they couldn’t hear what the people on the other side of the street were shouting. Meanwhile, the street itself was a ruin, full of potholes and debris and trash. And no one cared. All they wanted to do was keep shouting at one another.

Life in a collapsing nation

“Those days seemed like years,” Marlyn Rangel told me. “You didn’t know what day it was. To make things worse, without electricity you couldn’t charge your phone. So you didn’t know what time it was. Or the day of the week. You didn’t even know the date. You were isolated. There was no news. No TV. No radio. No cell phone signal. No data plan. No internet, no social media. No one from the government ever came to say what was going on. The government never sent water, never sent food or medicine. No police officers, no firemen, no rescue workers, no one to tell you what was happening and how long it would last. You were on your own. Alone, you and your family and your neighbors, every neighborhood an island surrounded by silence and darkness. The city an archipelago.

In Maracaibo, the country’s second-largest city, with nearly 2 million people, where Marlyn lived, the power stayed out for five days. And it didn’t come back on all at once. Some parts of the city were without power for longer periods of time, and in some areas it returned, only to go out again.

And as the days go by and there is no power and no news, you start to wonder: What if it doesn’t come back on at all? And then the food runs out. Or it spoils in the heat. And you have no cash (hardly anyone has cash anymore, because on top of the shortages of food and medicine, there’s a cash shortage). And without power the bank machines don’t work. And the stores can’t sell you food because the card readers don’t work. And it’s over 90 degrees. And there’s no air conditioning. And there’s no running water. And you can’t bathe.

In Maracaibo, the residents had been coping with blackouts and electrical rationing for more than a year before the big blackout hit, already desperate since 2017. Power would be shut off for about four hours a day, in different areas at different times, to ease the overall load on the grid.

Eventually rationing increased to about six hours a day. Over the next few months, it would fluctuate, sometimes longer, sometimes shorter. The schedule was erratic: you never knew when your turn would come. It was like a giant behavioral experiment to see how hundreds of thousands of people would react in an environment of increasing uncertainty and stress.

Maracaibo and the rest of Zulia state are at the far end of the nation’s power grid, almost as far as you can get from the big hydroelectric plants and still be in Venezuela. Yet they are reliant on those plants for most of the electricity they consume, which has created chronic problems. The state has several thermal generating stations, which operate on natural gas or diesel fuel. If they are operating at full capacity, they can provide nearly enough power to satisfy local demand. But most of those plants are either shut down or barely functioning.

During 2018, Nataly counted a total of 25 blackouts, some lasting just two or three hours, some more than a day. The longest blackout in 2018, in August, lasted three days. After that, the rationing became more intense: many people would go without electricity for up to half a day at a time. Toward the end of the year, it improved, and on some days there might be no rationing at all. Then it became worse again, and by February some areas of the city would be without power for up to sixteen hours a day.

You might think that the frequent absence of electricity would be conducive to better sleep—no lights to disturb you, no TV to watch, no bars or clubs to go to. But Maracuchos in general wear the irritable, beleaguered demeanor of the sleep-deprived. And it’s easy to see why. They spend nights in their cars, waiting in line to buy gasoline. They have to wake up in the middle of the night when the water suddenly comes on (often after weeks without running water), at which point they set to work filling tanks, washing clothes, bathing.

Without electricity there’s no air conditioning. Maracaibo, where the average high temperature every month of the year is over 90, and the nights are hot and full of mosquitoes. Most air conditioners sit like an outsize brick in the window because they burned out in one of the countless power surges. So people stay in their sweltering rooms with the windows closed against the bugs, tangled up in the clammy sheets, or lying outside in a hammock, sweating and slapping at mosquitoes.

Many refrigerators have been burned out by power spikes following the blackouts and brownouts, so people were caught unprovisioned. They had no food to last them till the power came back on. There was a day or two when the merchants were giving away perishables, like meat and dairy products, because they started to spoil. After that there was nothing at all.

On the fourth day of the blackout, Marlyn’s family ate the last of the food they had in the house: spaghetti with nothing on it. They had no dinner Sunday night and no breakfast Monday morning.

For a long time, people had been living day to day—money was short and food was so expensive that you couldn’t buy more than you needed for that day or maybe the next. I was in many houses in Venezuela in 2019 where you opened the kitchen cupboard and there was nothing inside, not a can or a crumb.

Venezuela used to be a land of plenty. People would say that to me all the time: We’re a rich country, we have oil. During the Chávez years, the country filled up with oil money—oil was over $100 a barrel—and these people who were going hungry now used to eat three meals a day and had enough money to take their kids to the movies or to the beach or to a fast-food restaurant. Now many people were eating just once or twice a day, and what they were eating was lentils. Maybe some rice or pasta. Tomorrow existed only as a doubt: What will we eat tomorrow?

People slept poorly or not at all; they didn’t bathe; they didn’t eat much, and what they did eat was mostly cheap calories: pasta, rice, lentils, with few fruits and vegetables and little protein.

They lived attenuated lives whose limits and constrictions were set by the irregular comings and goings of electricity, water, phone service, the internet, food, cooking gas, gasoline. It was all out of their control, a constant reminder of the power and the incompetence and the arbitrariness of the state. And of your own state of uncertainty. People became accustomed to just scraping by, putting up with what would have been unthinkable a few years or even a few months earlier. When power first started to go out, people were indignant. Now they hardly reacted. They used to have reliable running water. At first, when the water went away, people protested. Now they woke up in the middle of the night every few weeks when the water sputtered on and started washing clothes

The way Venezuelans talk about it, electricity is given and taken away. The government gives electricity just like it gives boxes of food or houses. And like gasoline, electricity is so cheap it might as well be free. With the devaluation and hyperinflation, the government electric company had essentially stopped charging customers. Whatever it might receive in payments wasn’t worth the cost of processing them.

People would stand in line for hours to enter supermarkets where they would buy whatever was on the shelves. Outside a large supermarket in El Tigre, I came upon a line of hundreds of people. They stood pressed one against the other, front to back. Stranger against stranger. They said that it was to keep people from cutting in line. There was something horribly dehumanizing about it, the way every person was squeezed between the person behind and the person in front. The desperation of it.

The residents of Santa Teresita were angry and afraid. They were afraid of the police and they were more afraid that the police would send the colectivos—the armed motorcycle gangs that served as the government’s shock troops. They were afraid that the colectivos would come and that there would be violence. People crowded around me. They saw that I was an American, a journalist. “When are the Marines going to come and overthrow Maduro?” someone said, a voice in the darkness. “You tell Trump we’re waiting for him,” said another.

Invasions come with casualties, I said. They don’t always go as planned. People are dying anyway, a man said. That’s right! A woman jumped into the conversation and they talked over one another: People are dying from hunger, being shot in protests, dying for want of medical care.

A woman told me that she’d just returned from a trip to Colombia, and at the border, Venezuelan National Guard soldiers stole the medicine she was bringing home: antibiotics, and drugs for high blood pressure and diabetes.

People told me about the arbitrariness of electricity’s coming and going, of the uncertain water supply. It robbed you of your sleep. That was the worst. Normally you slept with the air conditioner on. But without power, in the heat of Maracaibo, you had to leave the windows open or sleep outside, and the mosquitoes wouldn’t leave you alone. You could wrap yourself up in a sheet, but then you felt like you were suffocating and still you couldn’t sleep. On top of all that, you were on edge all the time. You were worried about your family, your neighbors.

A man listening to us broke in: “We’re the walking dead here!” “They’re killing us slowly,” Alejandro said. “We’re like zombies!” said a short, wiry woman with thin bare arms. Her words came out in angry, repetitive bursts. “They’re killing us! No food! No electricity! We’re going to disappear! Any day now!

The people here took care of one another. One woman had a mastectomy last week. Another suffered a stroke. Their neighbors checked in to see how they were doing. One family had two children with special needs. The woman who’d had the medicine stolen was bringing some back for a neighbor. But the neighborhood was emptying out. “Those folks over there went to Ecuador. The ones next door went to Peru. We’ve gone backward, to before the Second World War. To 1910. We’ve gone so far backward.”

One man survived out in the country raising rabbits to eat and sell. Everything was difficult: getting food for the rabbits, transporting the rabbits. He’d be stopped at a checkpoint and the soldiers would steal the rabbits. He lived in a shack with a tin roof and a dirt floor, cooking on a wood fire.

Middle-class people were spending the savings they had in dollars and wondering what to do when they ran out.

The farther you went from Caracas, the worse things were. And the worst of all, everyone said, was Maracaibo. If in some parts of Caracas you could squint your eyes and pretend that the world was normal, in Maracaibo, you could open your eyes and imagine that you’d arrived in the zombie apocalypse. The city felt depopulated. At least half the stores and businesses we passed were shuttered. There was no traffic, but there were long lines of cars at the gas stations, perhaps more than driving on the streets. A line of people waited at a bank for their turn at the cash machine. The daily withdrawal limits hadn’t kept up with inflation, so you could take out only enough money for a single bus fare. You had to come back the next day to withdraw the return fare. Parts of the city had no electricity because of the power rationing. If there happened to be other cars at an intersection where the traffic signals were out, you’d play chicken to see who would go first. Some drivers would cruise right through. Others would ease into the intersection, hesitating, foot on the brake.

Gas shortages had been chronic for years, since before Chávez, but as was true with everything else, it was much worse now. Mostly these days, there was no gas to be had. Then, when the gas arrived, you had to wait in line for hours, perhaps all day, to buy a cylinder. That was at the government price. You could probably find a cylinder on the black market, but it would cost more than a month’s wages.

The author went to a firehouse to tell them about a pickup truck on fire, where just two firemen and no vehicles remained. Not even a car. At one time there’d been 6 ambulances and several fire trucks. Now there were no ambulances at all and just one fire truck for the entire city at another firehouse.

By the start of 2020, Venezuela’s healthcare system was barely functioning. Close to half of the country’s doctors, some 30,000 of them, had emigrated. Medicines were unavailable or in short supply. Hospitals frequently had no electricity or running water. Equipment was out-of-date or broken. People were leaving Venezuela, not going there. At first it seemed that there were few cases of Covid-19. But it was only a matter of time. People who live day to day and have no food at home can’t stay inside for weeks or months waiting for the pandemic to subside. They have to go out and make a few bolivars to buy food. And people who have no running water and no soap can’t wash their hands. So while Covid was slow to take off in Venezuela, its spread inevitably accelerated.

By now authoritarianism had become a vocation and the government criminalized infection. Venezuelan refugees returning from other parts of Latin America were labeled as bioterrorists, intentionally bringing infection back to the country. The government strictly controlled the number of returning refugees allowed to reenter the country, forcing hundreds to wait at the border on the Colombian side. Returnees were placed in quarantine facilities, in crowded conditions, without basic hygiene or adequate food or attention. The government acted aggressively to control information as well. It began arresting reporters and medical personnel who posted information on social media that questioned or contradicted the official data. Doctors and nurses who questioned the readiness of the healthcare system or the government’s low case counts were intimidated and harassed.

Without cooking gas, people built wood fires using scraps of wood in the street or going up hills with trees or underbrush.

Looting

The looting started in Maracaibo late on Sunday, the fourth day of the blackout. The looters broke into a pharmacy and then an upscale mall. People were going down the street carrying packages of corn flour, rice, and pasta. In Marlyn’s house they hadn’t eaten since the day before and now food was literally walking past their door. La Curva was always a busy place, but Marlyn had never seen so many people there. They’d broken through the metal pulldown gates in front of the shops. People would run in, desperate to get their hands on something, anything. There was a chemistry in the air, almost a smell, you could sense it: desperation, adrenaline, a fever. It scared her. Suddenly Marlyn heard gunshots and she ran.

A group of men with guns stood outside a variety store called Todo Regalado (Everything Cheap), and they’d fired into the air to keep the looters back. But this was the only store that was protected. All around, the other stores had been ripped open and people were swarming in and out. The crush was so bad at some of the stores that many people couldn’t get in. When that happened, the people outside would start to shout, “Guardia!”—pretending to warn the looters inside that the National Guard had arrived. Scared of being caught, the looters inside would rush out. And then the people waiting outside would run in to take their places.

“It was like a game,” Marlyn said. “‘Guardia!’ Run out. Run in. Out. In. Out. In.” But there were no police, no soldiers. “It was absolutely out of control. The stores were like dark caves. There was broken glass, jagged metal. People were bleeding. Marlyn was too scared to go inside. “I felt like I was about three feet tall, like a hobbit. Everyone else seemed like giants, and if I went inside, I’d be crushed. She found a safe spot from which she could watch the parade of looters. People were taking more than food: electric fans, tables, chairs, a bed, blenders, pressure cookers, shoes, clothing, and even the shelves from inside the stores.

Later in the day Marlyn and her family followed the crowds to a warehouse. Inside there was a bonanza: pallets of food stacked to the rafters. This time Marlyn was determined to go in. But Andrés pulled her back. He was afraid she would get hurt. The boys went inside and soon came out loaded with treasure. Sacks of pasta, a case of canned deviled ham, laundry detergent, toilet paper, catsup, and a box of caramel candy. The boys dropped their booty and went in for more. Marlyn sat on top of the pile like a robber princess. They came out again with more stuff and now decided to head home.

“Morality, your sense of right and wrong, everything you learned when you were little, everything they taught you when you were growing up, everything they teach you in school, all the way up to college, was completely lost,” Marlyn said. “Why? Because people got to a point where they couldn’t think past tomorrow. What are you going to eat tomorrow? That’s the only thing that they have in their head anymore. No one cared about anybody else. If you die from hunger, what do I care, as long as I’ve got food. There’s no more lending a helping hand. People here, we have a tradition of helping each other out. If you come to my house: ‘Here, have some coffee. Do you want something to eat?’ People don’t do that anymore. You wait for the person to leave before you sit down to eat because you haven’t even got enough for yourself.

I didn’t have food. What was I going to do? Of course, everyone has their own conscience, everyone has their own way of thinking, every head contains its own world, but at the end of the day that’s what it was: I had food on my table that night. But what did that do to me? What about my conscience? Where was I? Where was Marlyn Rangel at that moment? I didn’t know her anymore.

in Maracaibo thieves stole the telephone wires that provided landline and internet service. The wire was made of copper, and the thieves sold it to scrap dealers. As a result, there was no internet.

On Sunday, looters cleaned out the Pepsi warehouse. On Monday, they looted Makro. On Tuesday morning the first looters showed up at a hotel. They broke a hole through the cinder-block wall at the back, backed up a flatbed truck and started loading it up. They knew what they were doing. A crew of looters went to the roof and removed the hotel’s four large air-conditioning units. Each one weighed hundreds of pounds. Word started to get around: They’re looting the hotel! More and more people showed up. The few hotel employees who had been able to make it to work that day fled before the wave of looters.

People were swarming over the hotel building, the grounds, the outbuildings, the cabañas, like ants on an anthill. People were running every which way. It was bedlam. A man whacke an electrical transformer mounted on a concrete pad with an axe until he broke through the steel shell and oil spurted out. Windows exploded as people smashed them, and on upper stories, men shoved mattresses out the windows and let them fall to the ground. Cars drove out loaded with loot. Others drove in to take their place.

In the midst of all the mayhem, people were acting like everything was normal. Looters went in and out, as casually as guests. Cars drove by on the main road, not fast, not slow, as though this were just another day—cars, a road, people, a hotel, destruction. The cabañas were stripped down to the studs. The roofs were gone, the doors, the windows, every toilet and sink and plumbing fixture, every inch of pipe, all the furniture, the wiring, the light switches. Every piece of equipment was gone from the restaurant: freezers, refrigerators, stoves, ovens, a fryer, dishwashers. The granite countertops from the bar had been pried up, the tables and chairs carted off, not as much as a spoon was left. The furniture was taken from the lobby. The computers were stolen from the front desk and the office, and everything else too, down to the staplers and the paper clips. The carpets were pulled up and the ceilings pulled down. All the copper wiring and the copper pipe was stripped away, as well as anything made from aluminum. The floor was littered with chunks of plaster and broken ceiling tiles. Ductwork and conduits hung down through great gashes in the ceiling. The looters had taken the doors from the rooms and the closets and the bathrooms, and when they couldn’t open a room, they broke the door down with an axe. Inside the rooms, all the furniture was gone—beds, mattresses, tables, chairs, lamps. All the fixtures were missing—sinks, shower heads, even the toilets. What they couldn’t take, they broke: windows, mirrors. The tan wallpaper, painted with white dogwoods, was scarred with holes where they’d pulled out the electrical sockets and the light switches.

The Government & Oil

What’s distinctive about Venezuela is that its economy revolves entirely around oil. The government owns the oil in the ground and receives money from oil sales. The effect of that is to put the government at the center of economic life. And the government’s main function becomes the distribution of the oil money to its citizens. This accentuated an existing tendency toward a highly centralized government with a powerful executive. Because an extreme amount of power (both political and economic) was concentrated in the government, an outsize amount of power was put into the hands of the president. And because there was always money from oil flowing in, the government never developed a strong tax base outside the oil industry. Income taxes, value-added taxes, property taxes, sales taxes—all were either nonexistent or charged at lower rates and with lower rates of participation than in other countries in the region. The Venezuelan state came to be viewed primarily as an enormous distributive apparatus, a huge milk cow that benefited those who were able to suckle at her teats.

And since distributing oil money was the main function of the state, it developed a patron-client relationship with the citizenry, whereby each constituency lined up to get its slice of the pie. Labor unions got a big bureaucracy with a large workforce and state-owned companies that hired more workers than they needed. The business community got state contracts and subsidies, including low-interest loans and reductions or exemptions to the already low taxes. Old people got pensions. Poor people got housing. The middle class got access to cheap dollars that subsidized trips abroad. Everyone got cheap gasoline, sold at some of the lowest prices in the world. And while governments in every country offer some or all of these benefits and pork directed at preferred constituencies, Venezuelans came to view them as essential attributes of citizenship—regardless of whether oil prices were high or low. It was like belonging to a special club—you expected all the good stuff and being born was the only dues you had to pay.

Chávez

Chávez was deeply conservative in an essential way. His discourse was aimed at the past more than the future. It was about recapturing a golden age, returning to an imagined greatness that never really existed. Like no other politician, Chávez lived and governed on television, by television, for television, cutting out the middlemen of the press and speaking directly to his supporters, the ones he chose to call “the people.” This was true from the very first moment that he burst into the cognition of his fellow countrymen to the very last time they saw him, live on television, 20 years later,

Chávez visited farms and factories; he rode horses, took walks, drove tractors. He sang. He danced. There were musical acts. There were special guests (Fidel Castro, President Daniel Ortega of Nicaragua). It started every Sunday at eleven A.M. but you never knew when it would end. It might last four hours or eight. He was on television almost every day. He broadcast cabinet meetings and speeches and tours of public works projects and trips abroad. He frequently commandeered the airwaves, breaking in and preempting the programming on all broadcast television and radio stations. From 1999 through 2012 he took over the airwaves in this way 2,377 times, for a total of 1,695 hours on the air. The whole critical mass of Venezuelan society had to watch the program, whether you were for Chávez or against him. All the heads of institutions had to watch because you never knew if he was going to call you, you never knew what he was going to come up with, you didn’t know if he was going to give you a direct order.

He would taunt and mock and skewer his opponents, at home and abroad. He would make announcements that his supporters knew would enrage his enemies, and because of that, they loved him even more.

In April 2002, Chávez used an TV to carry out a shake-up at PDVSA. He’d been in a long-running battle to increase his control over the government-run oil company, and a few weeks earlier he’d named several new members to its board. Ever since, the company’s workers and executives had been in revolt, staging protests and reducing production at wells and refineries. It was a test of wills—a defense of PDVSA’s independence from politics and a challenge to Chávez’s authority as president. Chávez took to the air and announced that he had a list of PDVSA executives that he’d decided to fire. When he was done, Chávez picked up a whistle and blew a sharp blast. “Offsides!” he said. “Get out!” Chávez’s fans loved the whole thing. They ate it up. They cheered. They clapped, on screen and at home. Did you see what he did? He fired them on TV! He fired them with a whistle! He showed those elite sons of bitches who’s boss.

This was in 2002, two years before Donald Trump would make entertainment out of firing people on TV. Chávez beat him to it.

If Chávez was visiting a farm and there wasn’t any livestock, the producers would truck in cows and release them in a pasture behind the comandante. Idle factories would receive the materials or equipment they needed to produce. His TV show was a televised Potemkin village—a stage set created for Chávez and the viewers that showed a shinier, more prosperous Venezuela than the one that existed. Chávez generally wasn’t in on the deception.

Oil prices were high and the government ramped up spending. It built thousands of apartments and houses and broadcast weekly televised giveaways, like game shows, where Chávez presented grateful families with the keys to their new homes. It spent millions to import washers and dryers and televisions and cars, which it gave away or sold at subsidized prices.

Chávez was a populist. The point of government for was staying in government. The point of power was staying in power. It wasn’t using that power to improve lives or make the country better in a lasting way. To the extent that any of those things were attempted, the attempt was made with a different end in mind: Would it help him stay in power? The core claim of populism is this: only some of the people are really the people. There is no more succinct description of Chávez’s 14 years in power. Populism, according to Müller, a professor at Princeton University, incorporates a moral vision that pits the pure people against the corrupt elites.

Chávez’s ideology was Chavismo, which is another way of saying that he was the boss and he would make the decisions. It was the same caudillismo that ran like a hauling rope through the nation’s history. Chavismo wasn’t a movement in any massive sense, but a following. The Venezuelan system of government has always been heavily centralized and weighted toward the presidency. And that suited Chávez and his cult of personality. What Chávez understood intuitively was that the way to stay in power was to exploit the “us versus them” dynamic of populism.

Chávez’s tendency was always to polarize,” said Izarra, Chávez’s former information minister. “That was the only way a revolution like his could function. He would say, ‘Polarize! We are good! They are bad!’ … Class struggle. Social class warfare. There’s no way to do that without polarizing. It has to be a no-compromise thing. There was no other way to move forward.

His stagecraft was brilliant, all alone on the stage, a lone figure in dark clothing surrounded by and elevated above the adoring masses in red. He holds a wireless microphone. Sometimes he grips it in both hands like he’s praying. His voice booms across the center of Caracas through giant speakers. An enormous campaign banner declares “Together forever.” “Who is the candidate of life?” Chávez asks the crowd. “Chávez!” they answer. Chávez works the crowd like a master. They cheer, they wave flags. He sings to them and they sing along. Nothing less than the life of Venezuela is at stake, he tells them. They reach a kind of ecstasy together.

Chávez had turned the military into the Bolivarian Armed Forces, loyal to him and his party. He brought in Cubans to set up an intelligence operation within the military, efficient and brutal, to root out dissent. He promoted loyalists and built a system of political indoctrination.

Gangs

Petare is often called the biggest slum in Latin America. Some 400,000 people live there on a concatenation of hillsides, ridges, and arroyos rising like a wall at the eastern end of the valley of Caracas. After the dictatorship ended in 1958, the new democratic government lifted the restrictions on squatting. People from the countryside poured into the capital and built their shacks on any piece of empty earth they could find. They started at the bottom and worked their way up the hillsides. The higher they went, the steeper it got, and where the roads didn’t reach, they built narrow, zigzag concrete stairways. Petare is one of the most violent places in Caracas, a violent city on a violent continent. Gangs control the barrio and fight over territory, and if you stray across one of the invisible borders separating them, you might not return. When Hilda was 12, one of her uncles was shot dead, in front of his family. When she was 22, her 17-year-old brother was returning from a party when he was shot and killed in the street. A couple of years later another uncle was hit by a stray bullet and bled to death. Hilda’s fourth child Yara disappeared on the way to the grocery store, and the police did nothing. They didn’t care about a lost little girl from a poor family in Petare.

The family printed posters with Yara’s picture. They searched everywhere. Hilda sold an electric mixer to pay for the posters and the bus and cab fare. Days went by. They put up more posters. Some of the kids fell ill and had to go to the doctor. A man called asking for a ransom. They sold the refrigerator and their bed to raise the money. But the ransom was a hoax. The man didn’t know where Yara was. On January 6, Yara’s body was found in a garbage dump. She’d been tortured. Her fingers and ribs were broken. Her hair was pulled out. But now that there was a body, the cops got interested. They put Hilda in a room and asked her why she’d killed her daughter. Hilda was furious.

The part of Petare where Hilda lives is run by a gang boss named Wilexys. He is feared and revered. He is the law in a lawless place. He helps the needy. Some months after Yara disappeared, Hilda received a phone call. It was Wilexys. He told her that he had found two men who had kidnapped Yara and sold her to another man, who owned a bodega. When the bodega owner tried to molest Yara, she’d resisted, and the man had beaten her to death.

It’s easy to see why Hilda and so many others of her generation loved Chávez. Suddenly the country filled up with money. This was not because of anything that Chávez had done. Instead it was driven by events halfway around the world—because economic growth in China and other countries pushed the price of oil sky-high. But that’s not how people in Petare viewed it. They voted to reelect Chávez for the same reason that people vote to reelect presidents in the United States when the economy is strong. Chávez was president and their lives were better. And he delivered for Petare. The government built medical clinics, installed water lines, and rebuilt the decaying staircases on the hillsides. It’s not that previous governments hadn’t done some of the same things. But oil prices had never been so high, and Chávez had more money to spend.

Venezuelan Death Squads

The FAES, as it is known, is a police force that was created by Maduro in 2017. It was proposed as an elite anti-crime squad, but it became clear early on that it had a different purpose. The FAES is designed to intimidate. FAES agents dress in black, with black body armor, and they often wear black balaclavas to hide their faces. They drive black pickup trucks without license plates and carry assault weapons and automatic pistols. The symbol of the FAES is a death’s-head, which agents wear in patches on their uniforms. The FAES carried out sweeps in poor neighborhoods, often resulting in a high body count. The dead would be identified afterward as criminal suspects who were killed while resisting arrest. After the killings, the FAES would plant weapons or drugs on the bodies of their victims, according to the report. In some cases, the killings occurred after the victims had attended anti-government protests.

In 2018, the government recorded 5,287 cases of killings due to “resistance to authority. Venezuelan human rights groups had reported an even greater number. At least 15,045 people were arrested and held for political reasons between January 2014 and May 2019.

In “Enforced disappearances,” the whereabouts of detainees were not revealed to family members or lawyers until days or weeks after their arrests. In most cases, people were held for exercising basic rights of free speech or political activity, and the detentions “often had no legal basis.” It found that people were repeatedly denied the right to a fair trial. In most cases, detainees were subjected to torture and other forms of cruel or degrading treatment. These included beatings, suffocation, waterboarding, and sexual violence.

The authoritarian turn was Maduro’s. With Chávez, there was protest but also money and good times. There were political prisoners, but not many. In the transactional relationship between the Venezuelan state and society, he had fewer plums to dole out, so instead he doled out violence and repression.

A United Nations report, released in late 2020, said that investigators had reviewed nearly 3,000 allegations of human rights abuses. The report concluded that they were part of “a widespread and systematic attack directed against a civilian population” and that they constituted crimes against humanity. I’ve talked to dozens of people who were beaten or tortured by security forces. Many of them were ordinary people, rounded up during protests.

BLACKOUTS

Three hours after the lights went out all across Venezuela on March 7, 2019, Maduro tweeted: “The electrical war announced and directed by U.S. imperialism against our people will be defeated!” A few minutes later, the communications minister, Jorge Rodríguez, went on television and announced that a foreign enemy had carried out a “cybernetic attack” against the large hydroelectric complex at Guri, in southeastern Venezuela. On day three of the blackout, Maduro spoke at a rally in Caracas. Government technicians had been close to restoring power to the entire nation, Maduro said, when another cyberattack had occurred, which set the process back to the beginning. He also revealed a new type of aggression. He said that the country had been the victim of an electromagnetic attack aimed at its power transmission lines. Maduro was very angry. He said that the Venezuelan opposition and the U.S. government were behind the attack.

A 2nd nationwide blackout occurred on March 25. This time Jorge said that snipers had fired on a transformer at the Guri complex, causing the transformer to explode.

One electrical technician said that so much effort goes into covering over mistakes and pointing fingers at others—playing the victim—rather than fixing the problem. Casting blame on outside forces or internal double-dealers is one of the essential traits of populism. A shared sense of persecution helps build the us versus them identity.

Chávez indulged in this and Maduro excelled at it: the claims of coup plots, assassination attempts, and sabotage multiplied. While Maduro and Jorge were claiming sabotage and outside aggression, other people were pointing to what everyone knew to be true: for years Venezuela’s electrical system had been decaying, suffering from massive disinvestment and a failure to maintain its installations. Like virtually everything else in the country, it was falling apart.

One of the most likely causes of the initial blackout was a fire under the high-tension lines. All electric utilities make it a priority to cut the underbrush from beneath high voltage lines, in part because a fire can produce a spike in current that can disrupt the transmission system. For years all types of basic maintenance, including cutting brush, had been neglected by the electrical utility

How did the nation with the biggest estimated oil reserves in the world turn into a disintegrating country where millions of people were going hungry and one in six residents had fled? The short answer is that Venezuela ran out of money. From 1999, the year that Chávez took office, through 2013, the year he died, Venezuela’s total oil export income was $768 billion. In 2012 the value of Venezuela’s oil exports reached its highest one-year level ever, surpassing $93 billion. Then the price of oil started to drop. In 2015, the nation’s oil export income fell to $35 billion. In 2016, it was just $26 billion.

We drive along lightless streets. Families sit in front of their homes, on stoops, in chairs, at tables, talking, playing dominoes, passing the time. The white light from our headlights engulfs them for an instant, like a strobe, capturing scattered images—a hand raised to place a domino on the table, a mouth opened in laughter. The light washes over them and moves on, leaving them behind in darkness. This is life now, post-electricity, which is to say pre-electricity, rushing forward into the past.

Many issues to fix the electric grid remain unaddressed. At the offices of Corpoelec 25% of the people are at work and they leave at two o’clock to make some money on the side. The same thing is happening in the power plants. In Guayana City there were only two workers assigned to do maintenance on close to 20 electrical substations. There was one old pickup truck available, and when it broke down, the workers paid for the repairs on their own, which they did since they used the vehicle to do odd jobs on the side to make extra money. To do their job properly, these workers needed a vehicle with a bucket lift, but they’d all broken down and never been fixed. Throughout the company, routine maintenance schedules had been allowed to lapse. At its peak Corpoelec had about 50,000 employees, but needed only half that many, swollen by profligate patronage and corruption and incompetence.

Corruption

Corruption destroys the idea of being a citizen. Everyone becomes complicit. Anyone who didn’t drink from the overflowing cup before it was empty and cracked, anyone who didn’t grab his fistful of dollars while he could was just stupid and to be pitied—no, not pitied: scorned. And that’s how the corrupt want it.

In Venezuela there have been two primary areas of commerce or industry into which people could channel their energy. One, of course, was oil. The other was importing. Since oil exports boosted the value of the bolivar and created strong incentives against producing things locally (this was the Dutch Disease effect), it was natural that the import business should thrive in Venezuela. Importing was also one of the ways that people could share in the oil revenues. The dollars produced by selling oil were used to bring in all sorts of things that consumers wanted. Food. Alcohol. Cars. Television sets. Clothing. Medicine.

In 2003 Chávez created a fixed exchange rate and a government agency, to decide who got dollars and for what purpose. This had two important effects. First, it put the government in charge of handing out dollars—accentuating its permanent role as the distributor of oil money and creating new avenues for corruption. Second, it led to the creation of a black market for dollars. Not all applications for dollars were approved. So you might want to have a friend or a cousin in the government, who could grease the wheels for you, and you might want to pay bribes to this friend or cousin and their friends.

Next, tennis rackets are nice, but money is nicer. So instead of spending the entire $1 million on tennis rackets in China, you arrange with your Chinese supplier to ship just $450,000 worth of tennis rackets to Venezuela, with a phony invoice that says the tennis rackets are really worth the full amount. Even so, once the merchandise arrived in Venezuela, customs officials might raise objections, and you might need to bribe them as well. That leaves you with $500,000. You could then take that money and deposit it in a bank account in Miami or Switzerland. Or you could turn around and sell it to other Venezuelan businessmen who needed dollars. And you would sell it to them at the black-market rate, which was double the rate you’d paid for the dollars. You could now take that money and spend it, or you could apply to buy more dollars. Venezuelans called that “the bicycle”: using the profits of one currency transaction to finance the next one, and the next one, and the next one. The wheels kept turning. You were playing with the house’s money.

The more you exaggerated the value of your shipment, the more you stood to profit. The incentives and opportunities for corruption were enormous for both importers and government officials. The orgy of dollars and bogus shipments became extreme. You could throw the tennis rackets you’d imported into the ocean and what would it matter? There were cases where importers didn’t bother to bring in anything at all, or they shipped containers full of scrap metal. Importers abandoned containers of merchandise on the docks because they had already realized such an enormous profit that they couldn’t be bothered to collect the merchandise and sell it.

Oil dollars ceased to be primarily a means of importing needed goods at an affordable price and became instead an object of speculation and corruption.

Even before the oil price started to drop, recession had set in, and the economy in 2014 would shrink by nearly 4%. At the same time, inflation was increasing and so were shortages of basic goods and lines outside depleted supermarkets.

Maduro’s response to inflation was price controls. Intended to keep basic goods affordable, they had the opposite effect. Cheap goods, including corn flour and other food staples whose prices were set below market value, were siphoned away from stores and resold on the streets at higher prices. The result was even more acute shortages and more inflation. Many goods also disappeared into Colombia and Brazil. Anything subject to price controls or produced with government subsidies—corn flour, shampoo, cooking oil, and more—chased higher prices across the border.

But the biggest cross-border profits were to be had by selling gasoline. Venezuela had the cheapest gasoline in the world—you could fill up your tank for pennies. There had always been contraband traffic of gasoline into Colombia. But as the economic crisis set in, the incentive increased.

With oil revenues decreasing, the government had less money to spend. But Maduro, intent on shoring up his political position, wasn’t willing to reduce spending. To cover the shortfall, he printed more bolivars, which produced more fuel for inflation. His response was more price controls and stricter enforcement. Low prices discourage companies from producing the controlled products, so there are fewer of them in the market. People rush to buy up the cheap products and stores run out. Then because the price-controlled products tend to be staples, those people who weren’t quick enough to buy them in stores still need them—and so the people who bought them resell them on the black market at much higher prices.

To keep its hard currency reserves from disappearing, the government restricted the sale of dollars. As with any other good, Rodríguez said, high demand and low supply meant the price of black-market dollars soared. As that happened, a growing portion of the dollars that the government sold to importers never resulted in goods coming into the country. The profits to be had by playing the spread between the official and black-market exchange rates were so great that would-be importers simply covered their costs and pocketed the money. All that meant fewer imports and fewer products on store shelves, which meant higher prices. At the same time, the government’s costs were going up too—salaries, pensions, military uniforms—and the government was printing money to finance its operations. As oil revenues fell, the government printing machine worked harder.

Maduro doubled down on price controls. He sent soldiers into electronics stores to mark down the prices of TV sets and computers. He added to the list of products subject to controls. He deployed an army of inspectors to audit stores and fine violators. The effect was to push more and more products onto the black market (or across the border), and store shelves became emptier. Lines at stores became so long the government assigned shopping days to people based on the last digit of their national identification number, and it sent soldiers to patrol the lines to make sure people weren’t shopping on the wrong day. If you had dollars, you were rich. You could buy a bottle of twelve-year-old Scotch for the equivalent of ten bucks, using bolivars bought on the black market.

Over time, the airlines cut back more flights, and the country, which had always been so open to the world, became isolated.

Working with Maduro was a shock. “I found myself with a person who was like Jell-O. He moves this way and he moves that way and he doesn’t make a decision. And the country, I felt like it was a boat that was sinking, down, down, down. Over time, however, Ramírez concluded that Maduro was listening to a group of businessmen who had made a fortune through easy access to Venezuela’s cheap dollars. And they didn’t want the system to change. “Maduro decided in favor of an economic interest group that had been at his side and had supported him for years,” Ramírez said. “Every time he either made a decision or didn’t make a decision, it was to favor that group.

I asked when the breaking point in Venezuela would finally come. She gave me the kind of look that a teacher might give a pupil who hasn’t mastered a lesson. “Things are never so bad that they can’t get worse,” she said. “They can.” I met de Krivoy a second time several months later, and true to her prediction, as grim as things had appeared before, they were orders of magnitude worse now. I asked de Krivoy how the country had come to this. “You start by weakening institutions. Chávez reformed the law of the Central Bank and allowed the Central Bank to fund the government. That opened the door to printing money and hyperinflation … Chávez sacked 20,000 professionals in PDVSA, changed the law [governing] PDVSA, turned PDVSA into a petty cash [source] for the government—and production started coming down. The process at PDVSA was complete, she said, when Maduro named a general with no oil sector experience to run the company. This was part of a broader pattern involving the military. First Chávez politicized the armed forces by making them loyal to his party, and then Maduro handed out key government posts to generals.

“Then you have the judiciary. Chávez increased the number of judges in order to control the Supreme Court, and the rule of law disappeared. Then you destroy property rights and overregulate the economy. Then you change the constitution and you start having yearly elections in Venezuela. So what used to be a 5-year horizon for policy making ended up being a one-year horizon, because every election in Venezuela was a referendum on Chávez, so the quality of policy making also deteriorated.

Maduro appointed Motta Domínguez as president of Corpoelec and minister of electrical energy in 2015. He had no experience in the electrical sector; he was a former general in the national guard. Maduro needed to shore up his support in the military and he was handing out sinecures to generals, regardless of their qualifications. Motta Domínguez also checked another box: he was close to Tareck El Aissami, a powerful governor who controlled an important faction within Chavismo. Corpoelec, even in its reduced state, was a juicy plum: there were patronage jobs to hand out and millions of dollars in contracts to assign. And he was utterly incompetent, firing some of the most essential workers keeping the electric grid up.

Under his leadership the grid fell apart. The 12 generators at Caruachi had been leaking oil and were surrounded by a lake of oil that no one had bothered to clean up. Basic maintenance had been neglected. Spare parts were exhausted. Radios didn’t work. Burned-out lightbulbs hadn’t been replaced.

People had deserted the company because they could no longer afford to live on wages that had once guaranteed a middle-class lifestyle and now provided for a starvation existence. Many experienced workers had left the country.

Where did the money go?

It is commonplace to say that Hugo Chávez had charisma and that this was the key to his success as a politician. And he certainly did have an ability to connect with people, especially those who had felt shut out for so long, pushed to the margins of Venezuelan political and economic life, the slum dwellers and the ranch hands and those left behind in the small towns. But more than charisma, what Chávez really had was the steadily rising price of oil. Put another way: oil at $100 a barrel is a lot of charisma.

In 2000, the year after he took office, Chávez had announced a National Rail Plan, which later would be renamed the Socialist Railway Development Plan. It was also sometimes called the Simón Bolívar National Railway System. The plan called for tens of billions of dollars to build or rehabilitate 15 rail lines with about 5,300 miles of track. The only part of it that was ever finished was a short commuter line connecting Caracas to a town called Cúa. The line covered 25 miles and had four stations. When it was finished in 2006, the government said that it had cost $3 billion. What struck me about the rail line beside the highway is that it was out in plain sight, for everyone to see. And what you saw was waste. And futility. There was a shamelessness about it, as though merely beginning were enough. As though promising something was all that was needed, and actually delivering on the promise was not what counted.

Promising and not delivering wasn’t something invented by Chávez. Building a train to connect Caracas to the central cities of Maracay and, further west, Valencia, had been talked about for decades. The difference with Chávez was the scale of the waste. He had more money than any of his predecessors to squander on miles of concrete and steel, on trains to nowhere.

The fact is that Chavismo was born of what came before it. Chávez’s greatest talent wasn’t inventing something new. It was just repackaging the old and pretending that he’d come up with it himself. The democratic governments in the four decades before Chávez had had their share of corruption and their share of wasted money. The Chavistas had either the good luck or the great misfortune to have been in power when the spigot was turned on all the way. You think of what could have been accomplished with all that money—how the country could have taken a different road, arrived at a different place. That is perhaps the greatest tragedy of Chavismo.

The great advantage of not finishing things was that you could come back every few years and announce them again: New Hospital Coming Soon! It was like a person who knows only one joke and keeps telling it over and over. And laughing each time.

There were so many avenues for waste. A paper plant sucked in more than $800 million and never produced a single roll of paper. An aluminum rolling mill was announced with an initial investment of $210 million. A few years on, Chávez complained about delays in construction and announced that he had approved an additional $500 million. In 2019, Maduro dredged up the rolling mill project again—more than a decade after its first announcement—and said that he was installing a new manager. On television, he wagged a finger at the man and said, “Get it done!” Six months later, the construction site for the project was quietly shut down.

In 2006 Chávez announced plans to build the country’s third bridge across the Orinoco River. He said it was one of Venezuela’s biggest engineering projects ever. Pilings were built, approach roadways were constructed. In 2012, the government said that it had spent nearly $900 million. In 2013, the transportation minister said the budget had increased to $2.8 billion. In 2014, he said that the project would be completed in 2017. Today there still is no bridge

The landscape is littered with unfinished projects. If you were a giant striding across Venezuela, you would have to watch where you stepped. You would stub your toe on an unfinished hospital here; you would howl in pain when you stepped on the pilings of an unfinished bridge over there. The exposed and rusting rebar poking up from half-built factories would be like splinters in the soles of your feet.

In 2005, Chávez declared his intention to make Venezuela a socialist country. He said that the nation would create a new kind of socialism that he called 21st-century socialism. No one ever knew what that meant. It wasn’t an ideology—it was a brand. The one thing that everyone knew about socialism was that the workers should control the means of production. Talking about socialism, then, meant making a show of acquiring the means of production for the working class. So Chávez embarked on a campaign of nationalizations.

His pockets stuffed with oil money, Chávez started buying back the privatized companies and went on a spree of expropriations and nationalizations. The national telephone company, CANTV, had been privatized in the 1990s. In 2007, Chávez bought it back, paying $572 million to Verizon, the largest shareholder. He paid about $1 billion for several privately owned power companies in order to create the single electrical utility that he christened Corpoelec and insisted on charging low rates—to protect the buying power of the poor and to buy support from the middle class at election time. But he didn’t provide the financing that would allow the company to perform maintenance and invest and grow.

You can make an argument that certain industries or certain types of companies might be better under public control. Many countries have public utilities and banks. But if you’re going to go out and buy up private companies and put them under government control, you ought to make an effort to run them well—to invest in them and to hire competent administrators. Chávez didn’t do those things. He put loyalists in charge and did almost nothing to prevent corruption. He starved his newly acquired companies of investment. The steel mill wasn’t for making steel, it was for making Chávez look like a socialist.

It couldn’t last, and it didn’t. That became clear on March 7, 2019, when the lights went out.

When Chávez wasn’t able to negotiate the purchase of a company, he would expropriate it, deferring the payment until a price could be fixed by an international arbitration panel. But that process took years, and the bills came due when Venezuela could least afford to pay.

Chávez expropriated a large gold mining project from the Canadian mining company Crystallex International in 2011. In 2016, an arbitration panel ruled that Venezuela must pay the company $1.2 billion. Another Canadian company, Rusoro Mining, won a judgment of $1.2 billion for another gold mine. Chávez seized the Venezuelan assets of ConocoPhillips, the American oil company, in 2007. Arbitration panels ruled that Venezuela must pay the company more than $10 billion.

Once Chávez had the properties, what did he do with them? Nothing. The gold mines were never developed. The oil ventures languished without sufficient investment.

Chávez created a national development fund, called Fonden, in which he deposited billions of dollars in oil money. The fund was under his direct control—a slush fund, pure and simple. He spent the money on large industrial or infrastructure projects or anything else he felt like supporting. From 2005 through 2014, Fonden received $142 billion from PDVSA and the Central Bank. That equals a fifth of oil exports during that period—under the sole control of the president, with no independent oversight and no consistent follow-up.

Chávez (and Maduro after him) also borrowed heavily, often using future oil revenue as collateral. Chávez established a series of off-budget development accounts with loans from China and investment from PDVSA. Between 2007 and 2014, these so-called Chinese Funds received a total of $62 billion, including more than $50 billion from China. As with Fonden, this money was under the president’s control.

When Chávez nationalized Sidor, the company had 5,600 employees. The total payroll eventually grew to more than 14,000 workers. It kept adding employees even as production fell. At the same time, the union came under control of the government and was effectively neutered. To be a unionist meant being a revolutionary, and that meant supporting the government, which was now the boss. Under Maduro, union leaders who asserted independence were jailed. Management was chosen based on loyalty rather than expertise. Corruption was commonplace. Rincón and Shiera had been paying bribes to receive contracts that allowed them to sell items such as pipe or drilling equipment at hugely inflated prices. The high prices provided for outsize profits for the two businessmen and also covered the cost of the kickbacks.

Investigators estimated that over a period of five years, Rincón and Shiera received contracts worth more than $1 billion. Their scam went along smoothly until PDVSA experienced a cash crunch, which caused it to delay payments to its suppliers. But adversity breeds opportunity. A Venezuelan lawyer approached Rincón and Shiera with an offer. He said that he represented high-level officials at PDVSA who could decide which suppliers were paid and which were not. These officials would make sure that Rincón and Shiera were paid on time, the lawyer said, if the businessmen kicked back to them 10% of everything that PDVSA paid them.

Santilli had sold PDVSA a consignment of 55-gallon drums for $9.2 million. Nothing could be more mundane: selling oil barrels to an oil company. But investigators said that the drums were actually worth just $2 million. In other words, Santilli was charging a markup of 360%. According to court documents, that was typical of Santilli’s transactions with PDVSA. The barrel sale occurred in October 2015, when the price of oil was in free fall and PDVSA could hardly afford to pay a $7 million premium for metal barrels.

Failed Projects

Since 2008 about $440 million had been spent to build the Bolivarian Cable Train for 0.6 miles of track while a similar system of 3.2 miles at the Oakland airport cost $484 million. Chávez suddenly showed up on TV screens everywhere to test Bolivarian Cable Train. It wasn’t even close to working, but the staff had rigged a car and short stretch of wire to make it appear as if ready, and it never was.

Everywhere were empty, dead, and dying houses. And there were gigantic holes in the ground, a monument of the broken promises. One hole had been intended to be a civic center for Maracaibo, a project started by President Carlos Andrés Pérez during the 1970s oil boom. Vast in scale, a marriage of culture and commerce, it would have office towers, a concert hall, a library, a stadium, and more. Plans were drawn up and a hole was dug, where foundations and subbasements and utilities and parking garages would go. But dig the hole was all they ever did. The project stalled. Presidents and governors came and went. The pit remained. It’s still there. It had become a dump site. All along the lip of the crater, trash was piled up, spilling into the void. It was hard to say how far down the hole went, but it was an impressive distance. At the bottom, there was a jungle, with trees.

Guayana City also had its holes in the ground, although none were as big as the Coquivacoa Hole in Maracaibo. A giant hole had been dug for a regional office of the Central Bank; it was to have had underground vaults to hold the gold from the Guayana mines. It was never built. I saw two giant holes excavated for shopping malls that were never constructed and one for a hotel.

Venezuelan Oil

Venezuela was becoming an oil-producing country that could barely produce oil. There are many reasons that production fell. American sanctions cut off the country from oil markets and from financing. PDVSA was badly managed. It failed to make necessary investments and maintain its facilities. Maduro had installed a general with no oil experience to run the company. By 2018, PDVSA wasn’t an oil company anymore. It was a junkyard. Thousands of employees had stopped going to work or fled the country because the wages PDVSA paid had become worthless. All the installations I visited were in ruins. Thieves stole the motors from pumpjacks and tore transformers off poles to remove the copper inside. Workers had no tools. Vehicles were broken down.