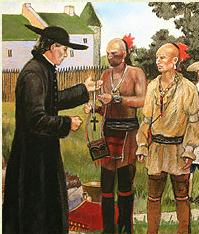

Preface. My first exposure to philosophy was in High School, about the philosophies that helped shape the U.S. constitution. This led me to read Rousseau, Hobbes, Locke, Montesquieu, and others. “Dawn of Everything” points out that Native American philosophies should have been given credit, since this is likely where some philosophers got their ideas from via bestselling books written by French monks and others who lived with natives while trying to sell them Jesus.

Alice Friedemann www.energyskeptic.com Author of Life After Fossil Fuels: A Reality Check on Alternative Energy; When Trucks Stop Running: Energy and the Future of Transportation”, Barriers to Making Algal Biofuels, & “Crunch! Whole Grain Artisan Chips and Crackers”. Women in ecology Podcasts: WGBH, Planet: Critical, Crazy Town, Collapse Chronicles, Derrick Jensen, Practical Prepping, Kunstler 253 &278, Peak Prosperity, Index of best energyskeptic posts

***

Graeber D, Wengrow D (2021) The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity.

Those closer to the coast were fishers, foresters and hunters, though most also practiced horticulture; the Wendat (Huron), concentrated in major river valleys further inland, growing maize, squash and beans around fortified towns. Interestingly, early French observers attached little importance to such economic distinctions, especially since foraging or farming was, in either case, largely women’s work. The men, they noted, were primarily occupied in hunting and, occasionally, war, which meant they could in a sense be considered natural aristocrats. The idea of the ‘noble savage’ can be traced back to such estimations. Originally, it didn’t refer to nobility of character but simply to the fact that the Indian men concerned themselves with hunting and fighting, which back at home were largely the business of noblemen.

Mi’kmaq natives in Nova Scotia, who had lived for some time next to a French fort said they ‘considered themselves better than the French: “For,” they say, “you are always fighting and quarrelling among yourselves; we live peaceably. You are envious and are all the time slandering each other; you are thieves and deceivers; you are covetous, and are neither generous nor kind; while as for us, if we have a morsel of bread we share it with our neighbor.” And consequently the Mi’kmaq insisted they were as a result, richer than the French. Yes the French had more material possessions, but they had other, greater assets: ease, comfort and time.

Twenty years later Brother Gabriel Sagard, a Recollect Friar, also came to the conclusion their social arrangements were in many ways superior to those at home in France. ‘They have no lawsuits and take little pains to acquire the goods of this life, for which we Christians torment ourselves so much, and for our excessive and insatiable greed in acquiring them we are justly and with reason reproved by their quiet life and tranquil dispositions.’ And like the Mi’kmaq, the Wendat were particularly offended by the French lack of generosity to one another: ‘They reciprocate hospitality and give such assistance to one another that the necessities of all are provided for without there being any indigent beggar in their towns and villages; and they considered it a very bad thing when they heard it said that there were in France a great many of these needy beggars, and thought that this was for lack of charity in us, and blamed us for it severely.’

The Wendat were also unimpressed by French habits of conversation. One Frenchman was surprised and impressed by the Wendat eloquence and powers of reasoned argument, skills honed by near-daily public discussions of communal affairs; while the Wendat often remarked on the way Frenchmen seemed to be constantly screaming over each other and cutting each other off in conversation, employing weak arguments, and overall not showing themselves to be particularly bright. People who tried to grab the stage, denying others the means to present their arguments, were acting in much the same way as those who grabbed the material means of subsistence and refused to share it; it is hard to avoid the impression that Americans saw the French as existing in a kind of Hobbesian state of ‘war of all against all’.

That indigenous Americans lived in generally free societies, and that Europeans did not, was never really a matter of debate in these exchanges: both sides agreed this was the case. What they differed on was whether or not individual liberty was desirable.

The 17th century European authors were nothing like us. Back then indigenous American attitudes are far closer to our own today. For example, 17th century Jesuits tended to view individual liberty as animalistic.