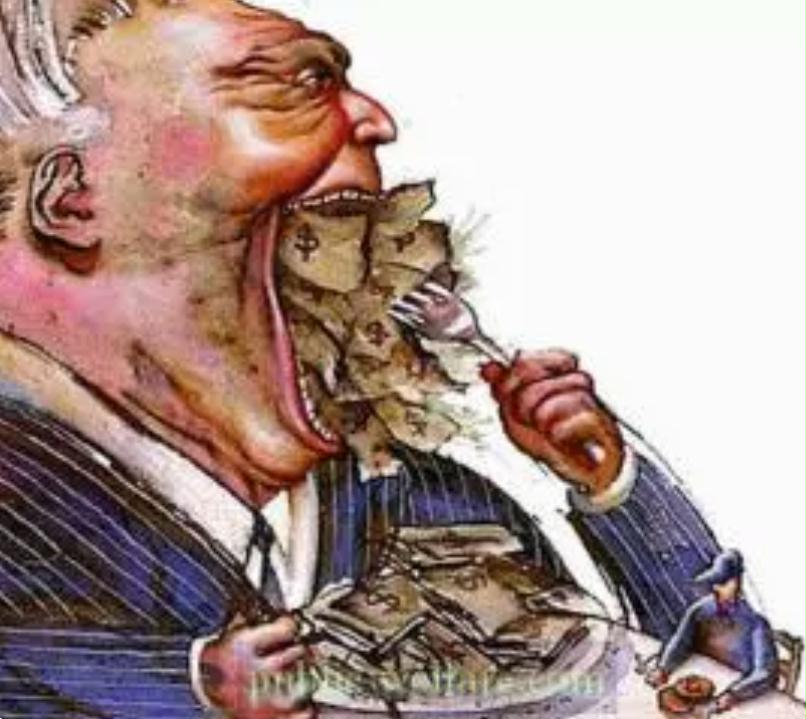

Preface. This is a book review of Frank Vogl’s 2021 book “The Enablers: How the West Supports Kleptocrats and Corruption – Endangering Our Democracy” (well, mostly kindle notes). They couldn’t get away with it if there weren’t so many places enabling sheltering ill gotten tains so easily, such as in Trump condominiums and banks that look the other way. In the end we all suffer as infrastructure falls apart, the division of wealth even greater, and the last remaining wild areas raped and pillaged for their mineral and agricultural wealth.

Corruption carries the seeds of its own destruction. Author Frank Vogl was a co-founder of Transparency International. You’ll see a strong correlation between poverty and (civil) war with how corrupt a nation is in the index at https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2021. And the least corrupt nations rank highest in the Happiest Countries of the world list.

Alice Friedemann www.energyskeptic.com Author of Life After Fossil Fuels: A Reality Check on Alternative Energy; When Trucks Stop Running: Energy and the Future of Transportation”, Barriers to Making Algal Biofuels, & “Crunch! Whole Grain Artisan Chips and Crackers”. Women in ecology Podcasts: WGBH, Jore, Planet: Critical, Crazy Town, Collapse Chronicles, Derrick Jensen, Practical Prepping, Kunstler 253 &278, Peak Prosperity, Index of best energyskeptic posts

***

Vogl F (2021) The Enablers: How the West Supports Kleptocrats and Corruption – Endangering Our Democracy.

Across the world, leaders of authoritarian governments, and their cronies, are robbing their people. These leaders are kleptocrats and they are pocketing staggering sums of cash, which they move through the world’s financial systems into investments in the wealthiest Western nations. These crimes perpetrated by the kleptocrats governing Russia, China, Iran, Egypt, Hungary, Nigeria, and many more nations not only impoverish their own citizens, but all of us.

Central to Western complicity with kleptocrats and their associates across the globe are the armies of financial and legal advisors, real estate and luxury yacht brokers, art dealers and auction house managers, diamond and gold traders, auditors, and consulting firms, based in London and in New York and in other important global business centers, who aid and abet the kleptocrats in return for handsome fees—these are the enablers.

They are motivated not only by the substantial incomes they obtain but also by the widespread failures of law enforcement across the Western democracies to impose punishments that are sufficient to serve as meaningful disincentives. At the major banks, for example, who have been prosecuted at times for multi-billion-dollar laundering of dirty cash, not a single chairman or chief executive officer has personally faced criminal charges for such activities, while the fines that are agreed to settle legal actions appear, quite simply, to be viewed by bankers as just the costs of doing business.

The short-term maximization of profits is at the core of the corporate cultures at many of the world’s largest banks and multinational corporations. They are giant enterprises and some of these banks have assets under management that dwarf the GDPs of many national economies. The drive for ever bigger and quicker profits, which translate into mounting bonuses for senior executives, push issues of integrity and accountability to the sidelines.

Never before has so much illicit finance flowed between nations. David Lipton, a former deputy managing director at the International Monetary Fund, has stated that the amount of private wealth estimated to be hidden in offshore financial centers, such as the Cayman Islands and the British Virgin Islands, amounts to $7 trillion, which is approximately 8% of global GDP. He noted that “much of which likely comes from illicit activities.

The clients of the enablers abuse their public positions for personal gain. Russian president Vladimir Putin’s kleptocratic clique includes his hand-picked Kremlin political colleagues; the top officials at major government departments, including justice, police, and the intelligence services; and the chief executives of state-controlled corporations; as well as a small number of old and close friends. In addition, there are the oligarchs, the enormously wealthy business tycoons, who have done a deal with Putin under which they secure their freedom to run their enterprises on condition that when Putin calls on them to undertake a favor, they click their polished heels and say yes.

Such cliques exist in all countries where national leaders have secured enormous power for themselves and manipulated the institutions of justice to ensure that they enjoy impunity. They steal public funds and enable corrupt practices in their regimes, for two prime reasons: rewarding and compensating their most valuable supporters to ensure their loyalty; and enriching themselves and their families.

Their thefts are at the core of sustaining their power and increasing their wealth. As best they can, they strive to keep their citizens in the dark about their massive thefts of public funds, blocking social media on the Internet, censoring mainstream media, taking government control of the major television and radio stations, jailing journalists, while curbing the activities of civil society. Not since the collapse of communism and the Soviet Union has the repression of citizens, including curbs on civil society and media, in so many nations been as great as it is now.

The kleptocrats need the enablers because they constantly strive to place their personal wealth in international, mostly Western, investment assets. They export their funds because they do not trust their national laws, and their wealth could be in jeopardy if they lose their power.

Our governments are engaging in a trade-off between concerns about the mounting power and wealth of the kleptocrats, and the benefits that accrue to our economies from the inflows of foreign capital, the taxes from the fees secured by the enablers, and trade and often security considerations. The views of our governments are influenced by the lobbying and campaign financing activities of financial institutions, including those that work for kleptocrats and their associates. The entanglements between Western governments, Western business, and kleptocratic regimes find our governments being complicit with these regimes, and right now the kleptocrats are winning. Western governmental complicity includes opening our capital markets, both to enable kleptocrats and their cronies to launder their loot into Western investments, and to enable kleptocratic regimes to borrow hundreds of billions of dollars every year from international investors.

President Ramaphosa, explained the situation in South Africa in 2021: “We do not have the money . . . that’s the simple truth that has to be put out there.” The breakdown of the country’s public services and the failure of the government to respond effectively have also been explained by South African political analyst Daniel Silke, who told the Financial Times: “We are finally seeing the effects of bad governance and low growth. South Africa is basically stuck.” And so too are all those dreams that millions of black South Africans who saw in the ending of apartheid the dawn of an era of prosperity. Memories of the dreams of post-communist, post-apartheid worlds of the early 1990s have faded. The new normal in so many parts of the world is national autocratic leadership by men who run increasingly corrupt regimes: Rodrigo Roa Duterte in the Philippines, Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi in Egypt, Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Turkey, and many more.

Plundering government coffers and securing incomes from state-owned enterprises have secured many African rulers in power for decades. Omar Bongo was the president of Gabon from 1967 to 2009, when he handed over to the current president, his son, Ali Bongo. Paul Biya has been president of Cameroon since 1982; Yoweri Museveni has been the president of Uganda since 1986; and Robert Mugabe was president of Zimbabwe for thirty years. They and the other so-called “Big Men” of African politics hand-picked the judges, appointed the chiefs of police and intelligence services, and so ensured that they enjoyed impunity. These tyrants survived by building legions of loyal supporters, punishing and jailing would-be opponents, rigging elections, and securing support, including foreign aid, from major Western aid agencies. While there were times when these donors demanded that the African governments hold elections, the fact was, and continues to this day, that elections in many African countries are a sham.

Corruption comes in many forms, but my concern, above all, is with grand corruption, the unrestrained abuses of public office for the personal enrichment of those entrusted with national political power.

Corruption is tracked at Transparency International’s (TI’s) Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI).

https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2021

In many of the countries that rank in the lower part of the CPI, kleptocrats and their cronies have total political power: for example, Azerbaijan, Belarus, China, Russia, Egypt, Syria, Gabon, and Equatorial Guinea. In others, powerful politicians are taking their governments down an ever more authoritarian road, leveraging their influence to gain an ever-greater stranglehold on all the institutions of government.

In some countries, formidable political power is wielded by corrupt military forces, controlling major non-military businesses, for example, Pakistan, Iran, and Myanmar.

There are other countries where freedom of the press continues and contested elections are held, but where vast theft of public funds by politicians and officials has become the norm, such as in Guatemala, Argentina, Kenya, Nigeria, and South Africa. Then there are countries, notably Lebanon and Bosnia-Herzegovina, where government exists on the basis of fragile power-sharing arrangements between different groups, where each group, in fact, steals its portion of public funds. These countries risk becoming failed states, or are already failed states, where corrupt warlords and powerful criminal gangs hold great power to govern and to steal, such as in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Somalia.

In the majority of the countries ranked in the CPI, national treasuries are plundered and a portion of the stolen cash is managed by enablers in Western capital markets; in most of these countries, there are senior government officials all too willing to demand kickbacks into their personal accounts from multinational corporations in return for public contracts. In addition, in a rising number of countries perceived to have corrupt governments, the national leaders feel all the more secure in their positions because of the expanding support being given to them by Russia and by China. The Russians are selling arms and expanding military deals. China has extended multi-billion-dollar loans to Asian and Latin American governments, and it is now the single largest official national creditor to sub-Saharan countries.

China is unique within the context of this book, both as a country riven with corruption throughout its senior government echelons, including its state-owned enterprises, and as an enabler of corruption across the world. Domestically, corruption increased over many years and there were high hopes in the country itself, and in the West, that Xi Jinping would be a breath of fresh air when in 2012 he became China’s president, general-secretary of the Communist Party, and chairman of the Central Military Commission. He immediately launched a massive anti-corruption campaign. As is now evident, it was his way of securing his authority and ensuring that the Communist Party remained paramount. Nepotism, gift-giving, and favoritism became so pervasive across the Communist Party that by 2012 it was threatening to undermine its authority. Xi’s “clean-up” has seen more than four million people investigated on alleged charges of corruption. Many of those investigated were viewed by Xi and his cronies as actual or potential political rivals. Some are prominent businessmen who for whatever reason were seen by Xi as a threat and whose imprisonment sends a signal to all citizens of China that no matter your business power, your first allegiance is to the Communist Party of China.

Discussing President Xi Jinping’s fortune is taboo in China and involves risks to foreign journalists.

China emerged in the second decade of the twenty-first century as the largest single official creditor to many developing countries, using its “Belt and Road” and other infrastructure loan programs to provide credits worth tens of billions of dollars to many governments for projects, the details of which are kept secret, and which provide borrowing government officials with opportunities for personal gain.

For some years, the US Treasury has suggested that the volume of laundered cash flowing into the United States each year is around $300 billion.

It is probably highly conservative to suggest that the annual illicit cash inflows are double the long-standing US Treasury estimate at around $600 billion. This total exceeds the 2019 fiscal year budget for the US Navy, Marine Corps, Army, and Air Force combined; it is considerably more than the annual sales of Amazon; and it is even greater than the total annual sales of the world’s largest retailer, Walmart, and Walmart accounts for 10% of all US consumer spending.

Economists at the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have estimated that global corruption costs 1.5 to 2% of global GDP and that the costs of corruption are upwards of $1.5 trillion to $2 trillion annually. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) reported that 57% of foreign bribery cases prosecuted under the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention involved bribes to obtain public contracts.

A significant portion of the funds that are stolen by politicians and officials in borrowing governments are invested in the West because we offer more investment opportunities, we have the best investment managers, and we have legal systems that protect investors in ways non-Western countries do not. The enablers get fees for managing the bond issues, and they get fees for managing the investments of the kleptocrats as well.

Dmitry Kozak headed the Olympic Preparatory Commission and suggested in 2013 that the Games would cost around $50 billion. They might have cost more, but the final cost figure has never been disclosed by the Russian government. The late professor Karen Dawisha noted in her landmark book Putin’s Kleptocracy that part of the costs of the Olympics were offset in 2013 by an 8.7 percent cut in government health spending and a further cut in the health budget of up to 17.8 percent in 2015.

Apart from kickbacks on inflated public sector infrastructure contracting, kleptocracies steal by controlling tax revenues and taking kickbacks from the rich in exchange for giving them tax breaks; selling state assets, such as sophisticated weapons systems to foreign governments with some of the proceeds directly going into their personal bank accounts; pocketing license and royalty fees from oil, gas, and mining companies; and placing relatives and cronies in charge of State Owned Enterprises (SOEs) that generate vast revenues, which are often diverted into buying political support and enriching politicians. SOEs are like piggy-banks for kleptocratic regimes. Often, the SOEs that provide the single largest flows of cash to the kleptocrats and their associates are those engaged in the energy sector, such as petroleum giant Pemex in Mexico, to electricity utility Eskom in South Africa, and to Russia’s largest international company, Gazprom. Such companies all work closely with enablers in Western Europe and in the United States as they invest funds and float international bond issues.

Money laundering is not just pursued by kleptocrats, but by organized criminal networks as well. HSBC’s American operations claimed to have failed to see red flags as vast sums of cash were being transported by planes and armored cars from the HSBC bank based in Mexico to its US branches. In 2007 and 2008 alone, the total amount transferred exceeded $7 billion.

According to calculations by the Boston Consulting Group, the fines paid by major banks for all assorted acts of wrongdoing since the 2007/08 financial crisis amounted to $321 billion by the end of 2016, including money laundering, sanctions violations, US sub-prime mortgage-related schemes, and other acts. Given the size of some of the schemes, such as those noted in this chapter, shouldn’t the top executives of the banks that have been caught red-handed pay personal penalties and be held fully responsible? So far, when it comes to the top executives of leading banks, the jailing of the former chief of the world’s oldest bank, Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena, is a rare exception.

Banking regulators have missed large loot-washing operations across the world. Are they just incompetent, or too trusting of the big banks, or so friendly with the bankers they are meant to be watching that they only rarely do thorough checks? The answer embraces all of the above. The result is startling: the banks launder hundreds of billions of dollars of loot, and the regulators, through their negligence, are effectively complicit in aiding and abetting the kleptocrats and their associates in their criminal behavior.

The world’s largest commercial banks wield enormous political influence to ensure that there is no halting their expansionist desires. They have grown in part through mergers and acquisitions of rivals, by securing official approval to enter into whole new business areas, such as investment banking. The bigger they become, the more concerned regulators have become to ensure that they remain strong pillars of the economy.

JPMorgan Chase is the largest global bank, except for the state-controlled Chinese banks. In 1970, when it was called Chase Manhattan, it had total assets of $22 billion, and by the end of 2019, after numerous major mergers and vast expansion, its assets stood at $2.69 trillion. The bank has been embroiled in multiple scandals in the last decade and paid heavy fines as a result, but always claimed that these were due to rogue employees.

Top bankers today continue to strive to expand their balance sheets, while constantly building their personal networks with influential politicians. Their dealings may be over meals in their private dining rooms at their banks, at conferences, in posh clubs, and sometimes at the opera or at sporting events. The fact is that the top bankers, their highly paid lead lawyers, their armies of lobbyists, and their “old college friends” in government are all members of a cozy establishment. Many of the institutional banking and government ties go back decades.

Top bankers today continue to strive to expand their balance sheets, while constantly building their personal networks with influential politicians. Their dealings may be over meals in their private dining rooms at their banks, at conferences, in posh clubs, and sometimes at the opera or at sporting events. The fact is that the top bankers, their highly paid lead lawyers, their armies of lobbyists, and their “old college friends” in government are all members of a cozy establishment. Many of the institutional

Banking and government ties go back decades. The United States is unique in regularly turning to Wall Street to select its Treasury secretaries. They come down to Washington, steer public policies, and almost always do so in ways favorable to the banks; then they often return to Wall Street!

I was once told that the ties between the bankers and the authorities in Switzerland run even deeper. On an individual basis, the key players often find themselves bunked together as they periodically have to serve for a few weeks at a time in the Swiss army, and many of them are old friends from their days in the elite Swiss universities.

Money matters. Consider the political contributions that the financial sector makes in US elections and, no doubt, the access and influence that these institutions hope to secure in return. Americans for Financial Reform (AFR), a nongovernmental group, found that financial firms spent almost $2 billion to influence Washington decision-making in the 2017/18 US election cycle. It noted that, “Since 2008, financial industry spending has increased to levels even higher than they were before the financial crisis, and the spending in this cycle was the highest yet for a non-presidential year.”

AFR’s list of the biggest spenders places the real estate brokers at the very top. AFR’s list of “Big Spenders”—the 20 companies and trade associations in the financial sector with the highest level of combined spending on lobbying and contributions (from their political action committees and employees)—is as follows:

- —$144,716,676 National Association of Realtors (NAR)

- –$96,481,469 American Bankers Association (ABA)

- —$25,769,494 Paloma Partners

- —$25,575,800 Citadel LLC

- —$20,596,381 Blackstone Group

- —$18,551,594 Soros Fund Management

- —$18,430,507 Euclidean Capital

- —$16,418,900 Renaissance Technologies

- —$16,274,122 Prudential Financia

- l—$15,454,408 Securities Industry & Financial Market Association (SIFMA)

- —$15,400,412 Credit Union National Association (CUNA)

- —$12,983,506 Citigroup Inc.

- —$12,280,155 Property Casualty Insurers Association (PCI)

- —$11,964,915 Investment Company Institute (ICI)

- —$11,903,162 Independent Community Bankers of America (ICBA)

- —$11,644,426 Goldman Sachs

- —$11,237,071 New York Life Insurance

- —$11,169,176 USAA

- —$10,907,945 Wells Fargo

- —$10,571,054

While the US banking authorities, the Treasury, the SEC, and the Justice Department all strive to monitor money laundering, bring cases against financial institutions, impose fines, and so rap a few knuckles, their EU counterparts are willfully negligent. Almost all of the money-laundering cases highlighted in the previous chapter involved European-headquartered banks, but by far the largest fines for their wrongdoing were levied by the US authorities.

Trump told Erdogan in 2018 he would intervene, and the problem would be “fixed” once prosecutors were replaced. Erdogan repeatedly sought to convince US officials to drop the case in the interest of Turkish-US relations. The Turkish regime did not reckon with Geoffrey S. Berman, who at the time was the US attorney for the Southern District of New York. He pursued Halkbank, asserting that it used front companies in Iran, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, and elsewhere to violate and to evade and avoid prohibitions against Iran’s access to the US financial system, restrictions on the use of proceeds of Iranian oil and gas sales, and restrictions on the supply of gold to the government of Iran and to Iranian entities and persons. He added: “High-ranking government officials in Iran and Turkey participated in and protected this scheme. Some officials received bribes worth tens of millions of dollars paid from the proceeds of the scheme so that they would promote the scheme, protect the participants, and help to shield the scheme from the scrutiny of US regulators.” Berman was forced by US attorney general William Barr to resign from his position in New York in July 2020. No specific reason was given. It could well be that President Trump feared that Berman would pursue investigations damaging to the Trump Organization or, perhaps, that Trump wanted a good relationship with Erdogan.

In no single area of finance is the relationship between governments run by kleptocracies, their Western enablers, and investors larger and more important than the bond markets. In no single area of financial transfers between countries, and between private investors and governments, does more cash flow into the treasuries and central banks of authoritarian regimes.

Because bond transactions are legal, irrespective of the lack of accountability as to where the proceeds go, the major international anti-corruption watchdog media and civil society organizations also fail to place the global sovereign bond markets on their screens. There is also a lack of transparency in parts of the debt markets, due largely to the secrecy that surrounds large-scale lending by China to governments.

The stock of international debt held by the governments of middle- and low-income countries, excluding China, exceeds $6 trillion. Fully $3.6 trillion of the overall total is concentrated in just ten countries: Argentina, Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Russia, South Africa, Thailand, and Turkey. Nobody knows just how much of this cash has been stolen by politicians and officials in the debtor nations. What is evident is that the thefts are now contributing to an evolving global sovereign debt crisis.

Corruption happens as bankers strive to secure deals from governments and so earn high commissions. Deutsche Bank provided substantial gifts to senior Chinese government officials, and it hired the sons and relatives of officials running SOEs. Those officials subsequently provided business to the bank, and recruited the children of prominent Russians as it sought to ensure that it won that country’s profitable government business. An e-mail from one of the bank’s executives in London, noted the importance of hiring a young Russian and pointed out that her father is “the deputy finance minister in Russia and had asked Deutsche Bank to hire her and if they did not find a permanent position for her as promised . . . this would significantly undermine our relationship with the government ministry.” In its court filing, the SEC noted that ten days after the minister’s daughter was hired, the bank received a request for proposal signed by the minister regarding a €2 billion Eurobond issuance, which was the first step to obtain the business.

On a far larger scale, Goldman Sachs raised $6.5 billion in three separate bond issues for the government of Malaysia’s Development Fund (1MDB) in 2012 and 2013. The bank’s fee for these deals was $600 million. US Justice Department charges brought against two former executives at the bank stated that more than $1.6 billion was paid in bribes to officials in Malaysia and their associates to win the bond deals and to provide them with access to what they hoped would be additional government business. These Goldman Sachs executives arranged the disbursement of the proceeds of the loans through a host of offshore shell companies into their own bank accounts, those of then Malaysian prime minister Najib Razak, and most notably an associate of the prime minister, Jho Low, who appears to have masterminded the schemes.

An investigation by US, UK, Hong Kong, Singaporean, and Malaysian authorities, which was the largest international cooperative investigation of its kind ever undertaken in the field of banking corruption, found that possibly as much as $4.5 billion of the funds were stolen. About $680 million alone was found in the private bank accounts of Razak. After he lost the election in 2018 and was ousted from office, his home was immediately raided by the police. They reported that they seized 12,000 pieces of jewelry worth up to nearly $220 million. Among them were 1,400 necklaces, 2,200 rings, 2,100 bangles, 2,800 pairs of earrings, 1,600 brooches, and 14 tiaras, along with about $29 million in cash, in twenty-six different currencies and 423 watches worth $19.3 million. The latter included more than 100 brands, among them Rolex and Chopard. Also found were 567 luxury handbags from 37 brands including Hermès, Prada, and Chanel. Investigators made a rough estimate that the Hermes handbags alone were worth $12.7 million. And 234 pairs of sunglasses worth about $93,000 were also seized. Najib remains a member of Malaysia’s parliament, despite having been tried on multiple corruption charges, found guilty, and sentenced to twelve years in prison.

Jho Low allegedly took a considerable amount of the total loan proceeds and, according to Justice Department filings, he invested more than $1.2 billion in the United States alone. He is wanted on criminal charges in several countries. Two former Goldman Sachs executives, Tim Leissner and Roger Ng Chong Hwa, have been prosecuted by US authorities, and Justice Department documents indicated that possibly a third executive might be charged. Goldman Sachs settled charges brought against it by Malaysian authorities by agreeing to hand over $2.4 billion, plus guaranteeing up to a further $1.4 billion to cover outstanding missing assets. And, no sooner had the bank settled the charges, than Wall Street stock analysts, underscoring that the fine was just a cost of doing business, declared this was a golden moment for investors to buy the bank’s shares!11 In late 2020, Goldman Sachs settled charges brought by other investigating authorities for a total fine of a further $2.9 billion—this includes about $1.6 billion going to US authorities in the largest-ever settlement of charges brought against a US company under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act of 1977 (FCPA).

The licit global bond deals involving kleptocratic governments dwarf the criminal ones and now raise major issues of global financial stability.

When interest rates in the major Western industrial countries are low, as they have been for more than decade, so the opportunity to secure higher yields for investors has increased the efforts of bankers to convince governments of poorer nations to also raise cash in the bond markets. Zambia, which has been riven with government corruption for many years, was the first sub-Saharan African country to access the private international bond markets in 2012. In 2020, it defaulted on its outstanding commercial debts (that is, it ran out of cash to make interest payments and principal repayments on its outstanding debts).

I really felt like saying to investors and bankers “serves you right,” when I read a story in the Financial Times in August 2020 (after President Lukashenko of Belarus rigged the elections and sparked huge public protests) that read in part: “Investors in Belarus’s sovereign debt are growing jittery about the threat of international sanctions against the country in the wake of last Sunday’s disputed election.” Of course investors and bankers oppose sanctions; after all, they want their money.

They also want the IMF to be constantly available to come to the rescue. Even before the 2019 election, the Macri government was in trouble and had to restructure the $65 billion, while turning to the IMF for help. The IMF provided a record-high line of credit amounting to $57 billion. Today, Argentina is awash in foreign debt that it cannot repay with a government that has a long history of corruption. If private creditors are confident about eventually getting their cash, then that is because of the IMF’s bail-out and the probability that the IMF will be generous when it comes to the terms upon which Argentina makes repayments.

Lebanon, whose government has been a cesspool of corruption and, accordingly, lost all public support, defaulted on its international loans in part because it appeared that the central bank’s accounts had long been far from accurate

Let me take you to Greece, the scene of the biggest sovereign debt default to private lenders in history. Negotiations between the Greek government, its official creditors at the IMF and the EU, and its private creditors took place in 2011–2012. The negotiations were a nightmare for all the participants and especially the victims: the millions of Greeks who experienced the worst depression seen in Europe since World War II.

The total amount of the debt that had to be restructured at that time was roughly equal to the total value of Greece’s economic output. “Restructurings” is a word that in this context relates to the amount of losses the investors are willing to take on their bonds, the extent to which they are willing to stretch out the time for the creditor to repay the debt, and how to assist the debtor to also manage the interest payments that it had originally agreed to make but could no longer afford. BNPP was Greece’s largest single private creditor, but other majors, such as HSBC and Deutsche Bank, were also prominent creditors, as were several hedge funds. All of them knew that they would be taking a big hit. The bankers had willingly made vast loans to one of the most corrupt governments in Western Europe without sufficiently evaluating the validity of the Greek government’s financial accounts.

You did not have to be an investigator to know what was going on. Taxi drivers in Athens would willingly describe the graft that dominated politics. Rampant public nepotism was pursued by the political parties to secure votes. Public funds were stolen regularly and in large amounts. A deal was finally struck that involved the creditors writing off more than $200 billion. The EU and IMF approved the deal, the bankers swallowed their losses, and the Greek people faced further pain.

By 2019, the size of the Greek economy was still 24% smaller than before the financial crisis in 2007. Hundreds of thousands of young and educated Greeks had left the country in the hope of finding jobs elsewhere. And Greece’s foreign debt now stood at a whopping $400 billion. None of the corrupt former Greek politicians was ever brought to justice. And, in the international bond markets, nobody has learned the prime lesson from this Greek debacle in the bond markets: beware of highly corrupt governments borrowing cash in the global markets.

The Russians are the masters of these markets. They borrow enormous sums and each time their enablers arrange deals undaunted by concerns that the cash fortifies a kleptocracy determined to undermine Western democracy. Bankers, lawyers, and investors in the City of London and far beyond kowtow to the Russians because it is good business. No enterprise in Russia does more to boost the personal income of Vladimir Putin and his circle of associates than Gazprom.

Egypt, a nation run by a corrupt military regime that uses cash it raises internationally to secretly purchase arms from North Korea,25 issued $2 billion of Eurobonds in November 2019. At the Group of Seven summit in France in 2019, President Trump waited to meet with Egyptian president Abdel Fattah el-Sisi and publicly and loudly declared: “Where is my favorite dictator?

Many of the governments of emerging market and developing countries know that they have no long-term prospects of repaying fully their foreign debts as they pile debts upon existing mountains of debts. Cash in staggering sums abounds in international waters, yet nobody really knows precisely its exact volume, on what borrowing terms it has all been secured, and how much it has boosted the personal wealth of kleptocrats.

Most parts of the sovereign debt arena are transparent, but China prefers secrecy. China is the single largest foreign official creditor to governments, and is particularly dominant in the foreign debts of some thirty countries, notably in sub-Saharan Africa. Combined, some fifty developing and middle-income countries owe China more than $380 billion, plus possibly a further $200 billion of what researchers at the Kiel Institute in Germany call “hidden debts.” The terms of these debts are a closely guarded secret between lender and borrower.

Many of China’s government loans to foreign governments have supported oil and mining projects, roads, railways, ports, and power plants under the aegis of the China’s “Belt-and-Road” (B&R) program, which was launched in 2013.

The Chinese may well extract concessions that enhance their political influence in the borrowing countries. In some cases, the collateral provided by the borrowing countries to the Chinese are natural resources assets or other businesses. Significantly, in some cases, the borrowers will draw on the IMF and other emergency cash inflows to pay the Chinese.

Their goals are to create major channels across the world to facilitate their commercial ambitions and, fundamentally, their global political ambitions. Their leverage now in terms of the debts owed to them by many nations may be effectively used by President Xi Jinping and his Beijing colleagues to support their national ambitions.

The Chinese are also international borrowers, and here again the bankers in the major capital market centers of the world are keen to do deals. Here too there are serious political and financial stability concerns, especially as the United States, for example, bends over backward to accommodate China’s financial goals and activities.

Kleptocrats and their associates like real estate in the poshest quarters of London, in the finest Manhattan towers, overlooking the Mediterranean in Monte Carlo, among the movie stars in Beverly Hills, and in scores of other locations far from their home countries. They are guided by three core investment principles—secrecy, safety, and liquidity—and fine properties fit the bill. There are legions of brokers, agents, and lawyers across the world only too happy to buy and sell fine dwellings to whoever, no questions asked

Investing in real estate is highly favored not only in North America and Western Europe, but also in other locations where asset values are high, such as Singapore and Dubai. Dubai plays an important role as a center for managing laundered funds. Some of these funds go into local real estate, but the stock of available properties is far too small relative to the inflows of dirty cash. Therefore, much of the money-laundering management that takes place in Dubai sees not only the inflow of cash and other assets, notably gold, notably from across Africa, the Middle East, and Asia, but also outflows via banking channels and often through offshore registered holding companies, and finally, into investment assets, including properties, in the much larger markets of North America and Western Europe The market is popular with wealthy individuals from Central and Eastern Europe, Central Asia, China, Greece, Pakistan, India, and the oil-rich kingdoms of the Gulf. Many of the purchased properties are rarely occupied.

Investigations by Transparency International-UK in 2015 found that “40,725 London property titles are held by foreign companies. 89% of these titles are held by companies incorporated in secrecy jurisdictions, covering approximately 2.25 square miles of London property. More than one third of all foreign companies holding London property are incorporated in the British Virgin Islands (13,831 properties), this is followed by Jersey with 14% (5,960 properties), the Isle of Man with 8.5% (3,472 properties) and Guernsey with 8% (3,280 properties). Almost one in ten properties in the City of Westminster (9.3%), 7.3% of properties in Kensington and Chelsea and 4.5% in the City of London (the financial district) are owned by a company registered in an offshore secrecy jurisdiction.

An investigation by Global Witness showed that over 87,000 properties in England and Wales are owned by anonymous companies registered in tax havens. The value of these properties is at least £56 billion according to Land Registry data—and likely to be in excess of £100 billion when accounting for inflation and missing price data.

The money was also invested in extending patronage and building influence across a wide sphere of the British establishment – PR firms, charities, political interests, academia and cultural institutions were all willing beneficiaries of Russian money, contributing to a “reputation laundering” process. In brief, Russian influence in the UK is “the new normal,” and there are a lot of Russians with very close links to Putin who are well integrated into the UK business and social scene and accepted because of their wealth.

The scale of property ownership via offshore holding companies on behalf of kleptocrats and their associates is probably even greater in the United States. A 5-part series of articles in the New York Times detailed the results of investigations into the ownership of 200 of the most expensive condominiums in Manhattan. The series of articles opened with the following that illustrates the issues: “On the 74th floor of the Time Warner Center, Condominium 74B was purchased in 2010 for $15.65 million by a secretive entity called 25CC ST74B L.L.C. It traces to the family of Vitaly Malkin, a former Russian senator and banker who was barred from entering Canada because of suspected connections to organized crime.

Many, perhaps most of the US real estate acquisitions by kleptocrats and their associates, and probably international organized crime figures as well, have been made by offshore registered holding companies whose true beneficial owners are hard to detect. A 2017 study by the US Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) found that 30% of all high-end purchases in major metropolitan areas (ranging from $3,000,000 in the borough of Manhattan, to $500,000 in Bexar County, Texas) involved beneficial owners or purchaser representatives who were the subject of previous suspicious-activity reports. Chinese investment in Western real estate could be even greater than that of the Russians. We have no idea.

Vancouver has long been a favored place for Chinese real estate investors. The government of British Columbia released a report in May 2019 that suggested that the cost of buying a home in B.C. increased by as much as 5% in 2018 due to more than $5 billion in dirty money from organized crime laundered through the province’s real estate sector. The report stated that C$47 billion in money laundering occurred in Canada in 2018. Of that, $7.4 billion was invested in B.C., making it only the fourth-highest in the country behind Ontario, Alberta, and the Prairies. The true beneficial ownership of large numbers of properties in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) is not known, but its scale suggests that many of the owners are possibly representatives of overseas kleptocrats or associated with organized crime.

A considerable amount of klepto-loot may well be invested in art. The international market for highly valued art is opaque and thus a kleptocratic dream. In a full-page article in the Financial Times in February 2020, the newspaper’s arts editor, Jan Dalley, wrote: “The art trade seems almost ridiculously tailor-made for money laundering.” Details of art deals, be they through art galleries or auction houses, are difficult to find in the public domain. The auction houses reserve the right not to disclose either the names of sellers of art that has been consigned to the auctioneers, or the buyers. Details of sales and purchases of art are just one part of the opacity of the global art scene. Often, major works of art seem to disappear altogether. Untold numbers of art masterworks are stored in private warehouses, and their true ownership is a closely guarded secret.

Russian oligarch Dmitry Rybolovelev reputedly owns a vast art collection, which came to light when in 2015 he sued his former art advisor and art dealer. The Monaco authorities started to look at his claims and at the warehouses. They also started to investigate the financial dealings of the Russian, who has sprawling interests, from the ownership of the Monaco FC soccer club to ownership of a mansion in Palm Beach that he bought in 2008 for $5 million from Donald Trump.

Illicit sales of diamonds have long been used as currency in the purchases of arms,

Kleptocrats and their associates want their cash to produce a good rate of financial return, but they are not inclined to take large risks. Cryptocurrencies, which until now have tended to have highly volatile valuations, are unlikely for the time being to be the investments of choice for them, although they may have more appeal for organized crime groups that seek to shift funds rapidly and secretly across the world.

Isabel dos Santos, long seen as the richest woman in Africa, with various estimates of her personal wealth of between two to three billion dollars, is the daughter of José Eduardo dos Santos, who was president of Angola from 1979 until 2017. The ICIJ came into the possession of thousands of e-mails and documents related to the dos Santos fortunes, which it called the “Luanda Leaks.” The ICIJ summarized its key findings as follows: Two decades of unscrupulous deals made Isabel dos Santos Africa’s wealthiest woman and left oil- and diamond-rich Angola one of the poorest countries on earth. Hundreds of millions of dollars in loans and contracts were directed to dos Santos’ companies.

Kleptocrats, their family members, cronies, and associates often require secrecy regarding all aspects of their investments. They invest their funds globally, and they are concerned that the citizens of their own countries remain ignorant of just how much of their cash has been stolen. They are no less concerned that political rivals and investigative journalists may use knowledge of the assets to damage their reputations. And, the more secretive they can be, the more they can operate beyond the reach of official foreign investigative agencies.

A prime means to secure secrecy is through so-called offshore holding companies. Skilled lawyers often design corporate structures, as described in the 2021 US Corporate Transparency Act, that resemble Russian nesting “Matryoshka” dolls, with one company layered upon another and then another and then yet another, all in an effort to defy detection and confuse investigators. While many of the disclosures revealed by the ICIJ’s Panama Papers do not all relate to illegal activities, many did. Individuals and institutions maintain offshore registered holding companies to secure privacy for their financial activities, which is legitimate when all income is reported fully to tax authorities. But, as the ICIJ noted: “Based on a trove of more than 11 million leaked files, the investigation exposed a cast of characters who use offshore companies to facilitate bribery, arms deals, tax evasion, financial fraud and drug trafficking.

Secrecy is not the only concern of the kleptocrats when it comes to their investments. Safety is no less a priority. They manipulate their national law enforcement institutions but know that should they ever lose power then their successors may turn those institutions against them, as the dos Santos family discovered. So they do not trust their own courts when it comes to their loot. They would much rather see any challenges over their investments pursued in British and American courts, which they consider to be honest and where they can hire the best and most expensive lawyers to defend their interests.

Public prosecutions related to money laundering are an uphill fight. Kleptocrats, or their enablers, if ever charged in Western courts can use their large funds to pay for teams of leading lawyers, often overwhelming the resources that government prosecutors can mobilize. Lack of cash is a critical constraint, assert public prosecutors on both sides of the Atlantic. It forces them to be very careful about which cases to pursue and it encourages them to seek settlements and deferred prosecution agreements, rather than pursue cases at large expense in the courts.

“The Big Four” of the auditing world dominate the world of auditing (KPMG, Price Waterhouse Coopers [PWC], Deloitte and Ernst & Young [EY]). They employ approximately one million people in roughly 3,000 offices across the globe. Meanwhile, “The Big Three” in global management consulting (McKinsey and Co, Bain & Co, and Boston Consulting Group) are vast enterprises with thousands of employees working on contracts for many governments and corporations. Like the largest global banks, these auditing and management consulting companies claim at times that “unfortunate incidents” are due to rogue employees, or rare weaknesses in compliance safeguards.

As added protection, let us call it insurance, the kleptocrats and their associates go to considerable lengths to polish their public images. Margaret Thatcher’s former PR guru, the late Lord Tim Bell, built a large firm representing such kleptocrats and their regimes as President Alexander Lukashenko of Belarus, President Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe, the governments of Bahrain and Egypt, and the foundation of General Augusto Pinochet (an old friend of Margaret Thatcher who stashed away his stolen funds in bank accounts at the now-defunct Riggs National Bank in Washington, DC). The demise of Bell and his company, Bell Pottinger, came when the media discovered in 2018 that he had been working secretly for a South African company controlled by the Gupta brothers in an attempt to divert public attention from their corrupt ties to Prime Minister Zuma. They hired Bell, who thought it would be a great ploy to promote stories in the South African media that white South Africans were exploiting blacks. His diversionary plan was to drum up old racial hatreds. In an article in the New York Times, Bell reflected what is perhaps the guideline for too many wretched consultants: “Morality is a job for priests. Not PR men.

I know of no individual who has done more to shine light on the vast problem of illicit trade finance than Raymond Baker, who set the stage in 2005 with the publication of his book Capitalism’s Achilles Heel: Dirty Money and How to Renew the Free-Market System. Baker, who went on to establish the Global Financial Integrity (GFI) think tank, saw the ties between illegal and corrupt trade, the widespread poverty in many emerging market and developing countries, and the challenges to the philosophical underpinnings of the free enterprise system. Baker has long been at the forefront of warning that the extensive bribe-paying related to commerce, and the money laundering that accompanies it, undermine the fair market competition that is at the core of capitalism, which has accounted for so much of our prosperity and fortified democracy.

Official data suggests that global arms sales are approximately an annual $200 billion. The five largest exporters in 2015–2019 were the United States, Russia, France, Germany, and China. The five largest importers were Saudi Arabia, India, Egypt, Australia, and China. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), the United States is by far the largest exporter, accounting for around 36% of the global total in the 2015–2019 period, followed by Russia with 17%. Saudi Arabia is a giant arms purchaser, taking one-quarter of all US arms exports, and 41% and 34% of UK and Canadian arms sales, respectively. Arms purchases by most emerging market and developing countries are largely shrouded in secrecy, with governments claiming that this is required on national security grounds, with the secrecy providing cover for corruption.

Surveys of the ethics and values of the largest international arms producers reveal an appalling picture. To sum up one major study that surveyed 127 companies: “Only 13 companies provide evidence of regular due diligence on agents. Only 8 companies have whistleblowing mechanisms that encourage reporting. Only 3 companies demonstrate good anti-corruption procedures in offset contracts.

When it came to promoting arms exports, then never before did American arms manufacturers have such a responsive and dynamic salesman as Donald Trump. His prime targets were Saudi Arabia and the other Gulf countries. His first trip as president in May 2017 was to Saudi Arabia, during which he announced the sale of “almost $110 billion worth of defense capabilities.” Selling arms to the Saudis and to other Gulf countries has long been a US government priority. Keen to boost sales Trump declared an emergency under the Arms Export Control in early 2020 to export $8.1 billion in sales for Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE).9 The Raytheon arms manufacturing company was encouraging the rapid completion of the sales10 and the president’s action was required to enable the sale to go ahead without formal notification to Congress.

The White House was keenly aware that the sales could have been blocked, following both Congressional statements against sales, fearing they would be used by the Saudis against civilians in Yemen, and in protest at the murder at Saudi hands of Washington Post journalist Jamal Khasoggi.

The United States is by no means alone in this regard. The UK and French governments have long been highly aggressive merchants of arms to the Middle East (Egypt and Qatar are the largest importers of French arms, accounting for 26% and 14%, respectively). No region of the world imports such a large volume of weapons and we’ll never know the full details.

The secrecy prevents investigations of corrupt payments, notably with regard to “offset” agreements that the Saudis and the UAE insist be part of major arms deals. These are side arrangements that may not be related to the military sector at all. Instead, they often provide funds for business sectors selected by the Saudi and UAE governments. These deal-sweeteners can be very large, “worth a third (in the case of Saudi Arabia) to almost two-thirds (in the case of UAE). In a $5 billion McDonnell douglas sale to the Saudis, one of the offset agreements established a factory to refine oils into shampoo and paint.

The intricacies of the offset deals are often directed by the Saudis, with some ventures involving senior defense officials, or new ventures where control is with a Saudi partner or Saudi agents, and no doubt commissions, to finalize arrangements.

Another key area of arms-related corruption concerns Western military engagements, and here the corruption directly adds to insecurity. In mid-2018 the U.S. had spent over $126 billion since 2002 to reconstruct Afghanistan, with $78 billion going to security. That total includes funding for roads, clinics, schools, civil servant pay, and Afghan military and police forces, not not the gar-greater costs of U.S. military operations in the longest war the U.S. has ever faught. The total exceeds all spending under the Marshall Plan that helped rebuild Western Europe after WWII. The US special inspector general concluded that corruption undermined the US mission.

The US Inspector General also issued a report in April 2018 that noted that many of the problems that have beset US development programs in Afghanistan are evident in the operations managed by the World Bank, which administers aid on behalf of international donors. These operations have involved more than $10 billion in expenditures. In sum, massive Western aid to Afghanistan over many years has disappeared and fueled the rampant graft in the country. The war continued year upon year to no small degree because the Taliban and other insurgents in Afghanistan secured powerful support from the Pakistan military and its ISI intelligence service, which is riven with corruption. Nevertheless, the U.S. has no compunction about shipping weapons to Pakistan, which could be used in the field against American troops.

And, then there are the challenges posed to Western and international security by the largest kleptocratic regimes, China and Russia. China National Petroleum Corporation’s former top echelon of managers was all purged on corruption charges soon after president Xi Jinping gained absolute power in 2012, and they were replaced by men who the Chinese regime are confident can pursue major national goals, including securing sources of international oil.

In quite a number of countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, the Chinese are engaged in large-scale investment projects, often through secret deals with kleptocratic regimes. Russia is not a passive bystander either. Both President Xi in Beijing and President Putin in Moscow have hosted high-profile conferences for African political leaders. We are unlikely to discover if lavish gifts or outright bribes are part of the Russian and Chinese diplomacy. Many deals, be they the publicly reported sales of Russian military equipment to NATO member Turkey or illicit arms sales from China and Russia to other regimes in developing countries, involve secret payment clauses.

Many of the worst crimes of corruption relate to the causes and the continuation of civil wars and mass violence. It is not a coincidence that many of the countries that are perceived to have the most corrupt governments are also those that are the scenes of the gravest violence. There is a statistically significant link between peace and corruption. For example, the same countries appear to a large degree in the lowest-ranking positions on both the 2017 TI Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI)21 and the 2018 Global Peace Index (GPI).22 Moreover, countries confronting the gravest terrorist threats tend as well to be those that have very low rankings in the CPI and GPI.

The record-level arms sales by many Western manufacturers to such regimes comes at a time when China and others are finding ever more sophisticated means to steal our technology; when Russia and Iran are supporting terrorist organizations and insurgent movements; when enablers in the form of middlemen and agents are mostly unmonitored by many arms manufacturers and serve as bribe-paying intermediaries; and when arms contracts with their complex offset clauses are often designed to hide bribes, and everyone in the business knows this.

Western governments are highly supportive of arms exporters because the industry employs tens of thousands of people and sales strengthen the trade balances. The industry contributes to economic growth, but also to war and to mass violence.

Democracy at Risk

American democracy is in trouble. So too is democracy in many other countries. The direct interference by authoritarian regimes in US elections has increased in recent years.

Integral to the Russian approach to undermine not only United States but Western democracy more broadly has been the deployment of Russian businessmen across Western financial centers, investing funds, forging deals, and deepening ties across the political establishments. In the United States, a critical component in the murky mix is the inability in many instances to understand fully where the money is coming from. Prominent Russians and Ukrainians, for example, were seen at Washington presidential inauguration celebrations in January 2017: Did they make illegal campaign contributions? Did they buy expensive tickets to the balls, which would have violated campaign laws? Who represented their interests and, anyway, why were they present at all?

The doors to unlimited cash in campaigns were thrown open by the US Supreme Court in 2010 in its verdict in the Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission case8 and its 2014 verdict in the McCutcheon v. the Federal Election Commission case. There is no way of knowing how much of the cash spent originates outside the United States and is channeled through diverse paths into political action committees ostensibly run by American organizations, just as there is no way of knowing the full scale of foreign lobbying in Washington, DC.

As few as 10% of all people doing political advocacy for clients in Washington, DC, are registered as lobbyists. By some accounts, about one-half of all members of the US Congress remain in Washington, DC, to advocate (read “lobby”) for clients.

Moscow has been able to direct so much political activity in Western democracies in large measure because of the failures of Western governmental investigative agencies to curb the laundering of Russian cash, and the activities of the enablers. The willingness of Western governments over many years to permit investments by shell holding companies whose true ownership has been allowed to be kept secret has aided the Russians. They are not alone. Governments in Iran, China, Turkey, and possibly others use shell companies and enablers to further their own political interests in the United States and other Western democracies.

Luxembourg, a tiny country with a population of about 600,000, has for many years provided tax avoidance opportunities to many of the world’s largest multinational companies. It has always been protected by its representatives in the EU Commission and on the Council, notably former EU President Jean-Claude Juncker, the former long-serving prime minister of Luxembourg. As author Nicholas Shaxson has noted: “Since the 1980s (Luxembourg) has run devastatingly successful campaigns in partnership with Switzerland (and sometimes Britain and Austria) to sabotage European efforts to crack down on tax havens, secret banking, shell companies and other secrecy devices.” Luxembourg has by far the largest number of investment funds of any EU country, and is second only to the United States. Finance is an enormous industry in this tiny country, which its authorities have powerful interests to protect, which in turn makes it highly attractive to kleptocrats and their associates when it comes to placing their cash.

In a world where governments willfully ignore year upon year the tax avoidance, tax evasion, and illicit financial transactions that abound, it is left to journalists with their slender resources to be the ones that shine light on dirty dealings. It took the “Panama Papers” for people from the UK to Iceland to Pakistan to learn that their top politicians have close ties to secret offshore shell companies.

Journalists played important roles in providing information to the FBI and IRS, which helped them to expose massive corruption in world soccer perpetrated by the Swiss-based Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) organization and its senior executives, including one who rented three apartments in Trump Tower in New York. Significantly, it was the US Justice Department, not the Swiss equivalent, that led the charge against FIFA.

The United States is the only country that provides large incentives to whistleblowers: hard cash rewards that, in very big cases, can amount to fortunes.

In Spain, the stench of corruption has infused politics for centuries, and it continues. In 2018, work by a brave whistleblower, Ana Garrido Ramos, contributed to the public disclosure of a scheme involving kickbacks for government contracts headed by a Spanish businessman who provided donations and bribes to the then ruling People’s Party, which led to the resignation of Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy and his government in 2019.

The enormous flows of dirty cash managed for kleptocrats by Western enablers, plus the large bribes paid by multinational corporations to foreign officials to win contracts, plus the multitude of non-transparent arms deals, all contribute to strengthening many kleptocratic regimes. The access of these governments and their state-owned enterprises to hundreds of billions of dollars in the international bond markets, through bonds managed by financial institutions in London and New York and other key financial centers that seemingly take no interest in just how the funds are used, adds to the entrenchment of the kleptocracies. In turn, these governments are increasingly curbing media freedom, curtailing the activities of civil society organizations, and jailing political opponents.

History shows us that authoritarian regimes are far more likely to go to war than democracies; that extensive government corruption contributes to civil wars; and that for the most part, democracies have a far better record of securing economic growth and reducing domestic poverty than kleptocracies.

When the music stops, in terms of liquidity, things will be complicated. But as long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance. We’re still dancing. —Charles Prince, then chairman and chief operating officer of Citigroup, in a 2007 interview with the Financial Times

The West’s largest banks have become larger and more powerful than many nations. They should have a core responsibility to serve the public interest by ensuring the health and integrity of the global financial system and the democratic values of the countries which host their headquarters. If their boards of directors do not recognize this obligation, then Western governments should act. The biggest banks are far too big to fail. They are crucial pillars in supporting the world’s economy, and because of this, the Western governments have obligations to ensure that the operations of these institutions are transparent, publicly accountable, and honest.

As of the end of 2019, the largest bank in the world (except for the government-owned leading Chinese banks) was JPMorgan Chase, which served half of all US households and had total assets under management at just under $2.7 trillion. This total exceeds the gross domestic product of France, the world’s seventh-largest economy, and it is more than $1 trillion larger than the eleventh-largest economy, Russia. Other US and European banks with total assets larger than those of Russia include Bank of America, Wells Fargo, Citigroup, HSBC Holdings, and France’s two leading banks, Crédit Agricole and BNP Paribas.

About forty banks headquartered in the West have assets under their control of around $1 trillion or more. The power wielded by the top executives of these banks reaches every corner of the world.

At too many of these enterprises, senior executives place their bonuses and compensation packages above the interests of their corporate stakeholders and the communities that their institutions are designed to serve. The decisions as to where to do business and with whom is, all too often, based solely on calculations of profit.

Sustainable reform of today’s complex money-laundering systems will be possible only when there are fundamental changes in the prevailing cultures that currently govern too many of the world’s largest banks and other multinational enterprises.

Several years ago, I spoke to the annual conference of the Florida International Banking Association in Miami, which brought together hundreds of compliance officers from banks across the Americas. At one point in my talk, I said that compliance is only effective when there is a clear tone at the top of the institution that the most senior managers value compliance work. To my surprise, there was loud and persistent spontaneous applause. Later, some of those in attendance told me bluntly that morale among compliance officers was low because in one bank after another it was clear that top executives took scant interest in the work. As one of the compliance officers told me: “We are just employed to tick the boxes—we might as well be robots.

The short-term profit maximization culture is in part driven by hedge funds and private equity firms that are consistently placing pressures on corporate management to find ways to boost their share prices. It is driven by the zeal of top executives, and in the case of banks by traders and wealth managers, to boost their bonuses. It is a product of the failure of corporate governance to counter excessive greed. Boards of directors are meant to provide a check on corporate managements, but this is rarely the case. In many of the largest US banks and other corporations, the chairman of the board and the chief executive officer are one and the same, and this one person has an outsize influence in selecting the other board members.

Their greed, narrow focus, failure to be sensitive to this broader responsibility, determination to out-compete their competitors, and willingness to “keep on dancing,” to quote former Citigroup chief Chuck Prince, contributed to the 2008 financial crisis and the great recession that followed. And it is contributing now to an increasing number of financial scandals and the explosion in sovereign international debt, which will lead to debt default crises in many countries and challenge the global financial system.

The approaches of the bankers have been fortified by the imbalance of their relationships with regulatory authorities, as described in chapter 5. The banks are large-scale political campaign contributors and employ large lobbying forces to influence public policies. The lead-up to the 2008 crisis saw banking regulators and central bankers basically accepting that the bankers knew best, that the risks were being well-managed, and that market forces would anyway produce effective responses to excessive developments. The complacent and compliant regulators share much of the blame

The antagonism of the bankers emerged on full display in their opposition to many aspects of the Dodd-Frank law, which was passed as a response to the 2008 financial crisis and sought to limit some of the activities of the banks and increase their regulation. Numerous top US bankers resented the way the US government’s bank bail-outs had been managed, the pressures placed on the banks to follow US Treasury directions, and the tidal wave of support in Congress for tough new regulations. Above all, they resented how the combination of all of these actions, along with universal media condemnation of the activities of many financial institutions in sub-prime mortgage transactions, had damaged the reputations of the banks and, of course, those of the men who ran them.

In late 2013, Jamie Dimon, the chairman and CEO of JPMorgan Chase, the world’s largest bank (apart from the largest state-owned Chinese banks) met with then US attorney general Eric Holder to settle allegations that JPMorgan Chase had overstated the quality of mortgages that it was selling to investors prior to the 2008 financial crisis. Those sub-prime mortgages were acquired by millions of Americans, who discovered that they could not service their debts and who lost their homes. JPMorgan Chase’s actions contributed to the worst crisis of home foreclosures in American history, and the bank’s final settlement with the Justice Department amounted to $13 billion, which was the largest fine it had ever paid. In January 2014, JPMorgan Chase’s board of directors announced that Dimon’s total 2013 compensation was $20 million, up from $12 million in the previous year. No doubt, a part of the big pay package was a reward to Dimon for negotiating a lower fine than the bank’s board of directors had expected (Bank of America’s fine on similar charges was even larger at $16.65 billion). In an earlier era, the board might have fired Dimon for overseeing such terrible banking practices!

If the banks are unwilling to change their high-risk cultures, then regulators need to double or treble the levels of fines, force the banks to cut their dividends, and pressure boards of directors to fire top executives. Only such measures, at a minimum, are likely to lead to substantial shareholder pressures for fundamental cultural reforms. The top individual bankers must also be held to account. This has long been a concern for Senator Carl Levin, a Democrat from Michigan who served in the US Senate for thirty-six years. He chaired the Senate’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations for many years from 2001, and in his memoir he underscored his disappointment that settlements, including fines, imposed by the US Justice Department failed to alter the culture in banks that had so gravely endangered the nation’s economy.

He wrote: But individual accountability is equally important—maybe more so—because without it the wrongdoers can simply carry on with their lives and keep most of their wrongful gains as if nothing happened. The failure to prosecute responsible individuals in those corporations that did so much economic damage to so many people and the economy (in 2008) is a tragedy. If the excuse is that the laws are too weak to prosecute, then the laws need to be changed. Individual accountability in corporate America is essential to keep the greed in check. The government must hold large corporations and the top people in them accountable for their wrongdoing to restore public confidence in law enforcement and the financial system and to ensure our laws are being equally enforced against the powerful.

Today the budget resources available to the FBI, the Securities and Exchange Commission, and the US Treasury are inadequate. For example, the US Treasury’s FinCEN department has the responsibility to monitor and review all suspicious international financial transactions caught by bank compliance operations, which can amount to millions of filings and reports: in 2019, FinCEN had only 332 staff analysts and $118 million in Congressionally appropriated funds. It is a budget that is totally inadequate to enable it to fulfill its mission, which the Treasury states is “to safeguard the financial system from illicit use, combat money laundering, and promote national security through the strategic use of financial authorities and the collection, analysis, and dissemination of financial intelligence.” The resources available to FinCEN are miniscule compared to the vastness of money laundering today and the resources available to those who enable money laundering. Resources for investigations and prosecutions are also inadequate.

As the kleptocracies gain wealth and greater security in their positions of power, most notably those at the helm of nuclear powers, China and Russia, so a new form of “Cold War” has emerged: powerful kleptocratic regimes are intent on expanding their power well beyond their borders and weakening democracies as they do so.

They continue to be concerned about the misuses of the financial system to finance terrorist organizations. And, they are increasingly well-informed on Russian and Chinese illicit actions in the United States: cyber-attacks, hacking government agencies and corporations, and other actions often financed by dirty cash.

The anti-corruption provisions mirror legislation proposed in 2018 by Democratic Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts. Her bill was a blueprint for reform that included detailed proposals under such headings as conflicts of interest, lobbying reform; rulemaking reform; judicial ethics; enforcement; and transparency and government records. Underscoring the ties between domestic and international anti-corruption reforms, Warren’s proposals included, for example: “End Influence-Peddling by Foreign Actors . . . end foreign lobbying by Americans by banning American lobbyists from accepting money from foreign governments, foreign individuals, and foreign companies to influence United States public policy.” The Republican Party leadership refused to bring her legislation to the floor of the Senate for debate.

According to the Rasmussen polling group in April 2019, 53% of US voters believe political corruption is a crisis in the country, while a further 36% consider it a problem. The group said the data is consistent with other polling data showing 87% of voters see corruption as widespread across the federal government. And Pew Research, which has been tracking public perceptions of trust in government for more than forty years, found in 2019 that only 17% of citizens trust the federal government to do the right thing always or most of the time—the lowest level ever recorded. You can find similar results from opinion polls in Europe.

The far-reaching public distrust of government in much of the West also reflects deep concerns that our governments have failed to keep their promises and secure a better life for most citizens. These concerns crystallize around wealth and income inequality, and many people believe the issue is fundamentally about corruption, about a system where the wealthy have the most influence in politics and gain vast profits at the expense of the great majority of the citizenry. This fosters a sense of resentment and provides a basis for the public appeals by populist politicians. A 2019 analysis by the US Federal Reserve Board of wealth distribution found that fully half of all American households combined now hold an almost invisible 1%. No wonder citizens are angry with their governments, given that the official data shows the majority of households are in real terms worse off than they were several decades ago.

As Reich succinctly noted: “When most people stop believing they and their children have a fair chance to make it, the tacit social compact societies rely upon for voluntary cooperation begins to unravel. In its place comes subversion, small and large—petty theft, cheating, fraud, kickbacks, corruption. Economic resources gradually shift from production to protection.

Populist politicians can and do take advantage of conditions where the establishment political parties have all been publicly vilified. Men like President el-Sisi in Egypt, President Erdogan in Turkey, Prime Minister Orban in Hungary, and numerous others have gained power as a result, then moved swiftly to curb democracy, establish authoritarian regimes, and enable widespread grand corruption.

Nevertheless, the public protests will likely continue in increasing numbers of countries, as wealth and income inequality continue to increase, as poverty rises, and as the public, made all the more aware through social media, demands governmental accountability and transparency. Western governments and Western businesses cannot ignore these developments, nor can they ignore the growing impatience in Western democratic countries themselves, as evidenced by the opinion polls noted above. It would be wrong to underestimate the degree to which US public support for the presidential campaigns of Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren in 2020 was due to the forthright anti-corruption views of these candidates.

The United States is the only country that provides large incentives to whistleblowers: hard cash rewards that, in very big cases, can amount to fortunes.

In Spain, the stench of corruption has infused politics for centuries, and it continues. In 2018, work by a brave whistleblower, Ana Garrido Ramos, contributed to the public disclosure of a scheme involving kickbacks for government contracts headed by a Spanish businessman who provided donations and bribes to the then ruling People’s Party, which led to the resignation of Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy and his government in 2019.