Preface. When I first published this post in February of 2022, I said that peak world oil production might have peaked in November 2018, but it takes 5 years in the rear-view mirror to call it. So while it did peak in 2024 based on production in 2023, that may not be true after all. Some of those years were affected by the covid-19 pandemic. Since then, Permian oil production and Canadian oil sand production has ramped up, so crude oil and condensate production in 2024 will be roughly equal or slightly exceed 2018 production.

Art Berman believes that world oil production will be 2030-2035 and not fall off a cliff, so whenever it happens, there will still be a lot of oil left. But what he does not consider is that only crude oil and condensate matters, that is where transportation diesel comes from to power trucks, ships, and locomotives. World peak oil also includes NGLs (natural gas liquids) that are very light and best for plastics and other petrochemicals. And ethanol, which destroys diesel engines and has a negative EROI.

So I suspect that diesel peak is sooner. But to hell with a date. Oil is finite. “Renewables” can not replace fossil fuels, and we are exceeding at least 6 of the 9 planetary boundaries and other polycrises.

WE ARE RUNNING OUT OF TIME.

Perhaps NGLs and other liquids were added to keep people from panicking like they did in the oil crises of 1973 and 1979. Though that won’t happen perhaps the next energy crisis given how much people believe in renewables and ghosts and hundreds of Gods and whatever else they want to believe, would probably not worry.

Oil may decline for non-geological reasons such as financial crashes, wars, natural disasters, the export land model (the few oil producing nations left keep the oil for their own population and factories), oil chokepoints, and black swans. I think a great deal of oil will be left in the ground. Geology isn’t the whole issue.

Above all, it is the FLOW rate that matters. Half the oil may still be underground, but the 30% of it in unconventional reserves will take longer and be more expensive, returning less energy to society.

Delannoy et al (2021) estimate that by 2050, half of the gross energy output will be engulfed in its own production. Whoa — if the EROI of civilization needs to be at least 10 to 14, that’s the end of civilization (Lambert et al 2014)!

FYI, A good primer on oil, drilling, refineries and more: Petroleum, or crude oil, is a fossil fuel and nonrenewable source of energy. National Geographic.

Alice Friedemann www.energyskeptic.com Author of Life After Fossil Fuels: A Reality Check on Alternative Energy; When Trucks Stop Running: Energy and the Future of Transportation”, Barriers to Making Algal Biofuels, & “Crunch! Whole Grain Artisan Chips and Crackers”. Women in ecology Podcasts: WGBH, Financial Sense, Jore, Planet: Critical, Crazy Town, Collapse Chronicles, Derrick Jensen, Practical Prepping, Kunstler 253 &278, Peak Prosperity, Index of best energyskeptic posts

***

Peak oil in the news

2022. Oil Frackers Brace for End of the U.S. Shale Boom. WSJ.

The end of the boom is in sight for America’s fracking companies. Less than 3½ years after the shale revolution made the U.S. the world’s largest oil producer, companies in the oil fields of Texas, New Mexico and North Dakota have tapped many of their best wells. If the largest shale drillers kept their output roughly flat, as they have during the pandemic, many could continue drilling profitable wells for a decade or two, according to a Wall Street Journal review of inventory data and analyses. If they boosted production 30% a year—the pre-pandemic growth rate in the Permian Basin, the country’s biggest oil field—they would run out of prime drilling locations (the “sweet spots”) in just a few years. For years, frackers told investors they had secured enough drilling spots to keep going for decades. But the limited inventory suggests that the era in which U.S. shale companies could quickly flood the world with oil is receding, and that market power is shifting back to other producers, many overseas. Big shale companies already have to drill hundreds of wells each year just to keep production flat. Shale wells produce prodigiously early on, but their production declines rapidly. The Permian is expected to be the longest-lived U.S. oil region and is home to more than 80% of the country’s remaining economic drilling locations.

What?! the WSJ said there are limits to growth? That fracked oil supplies can’t grow without being depleted in a few years? The WSJ is famous for saying there are no limits to growth, perhaps because if it were true there’d be no justification for their libertarian rape and pillage of resources to make a few people very rich: ‘Limits to Growth’; a Dumb Theory That Refuses to Die, New Limits to Growth Revive Malthusian Fears, Could Resources Become A Limit to Global Growth?, The World’s Resources Aren’t Running Out, etc.

2021 The Incredible Shrinking Oil Majors “… the future for these companies has gone from challenged to incredibly bleak. Over the last 20 years, oil supermajors Exxon, Chevron, Royal Dutch Shell and Total have found it challenging to maintain their reserve base and production level. Even though upstream capital spending has surged, production and reserves have persistently declined. Things look significantly worse if you focus only on crude oil. While Exxon’s crude oil production has declined by 8% over the last 20 years (in line with gas production), Royal Dutch Shell’s crude production has collapsed by 20% while Chevron’s has fallen by 7%. While Total is once again the only company to show any growth, it has been modest: oil production is up 0.8% CAGR over the last 20 years. Proved oil reserves tell a similar story. Exxon’s proved oil reserves are down 26% while Royal Dutch Shell’s have collapsed by 57% and Chevron’s have fallen 29%. Even Total’s proved oil reserves have contracted by 16% since 2000. While all four supermajors saw their total proved R/P ratios fall by 26% on average, their oil-only proved Reserves/Production ratios fell by 30%.”

2019. When will ‘peak oil’ hit global energy markets? dw.com. Darren Woods, CEO of ExxonMobil predicts a 25% rise in global energy demand for the next two decades, due to “global demographic and macroeconomic growth trends. When you factor in depletion rates, the need for new oil grows at 8% a year,” he told analysts in March.

FYI, if you’re curious about what oil looks like, go here.

****

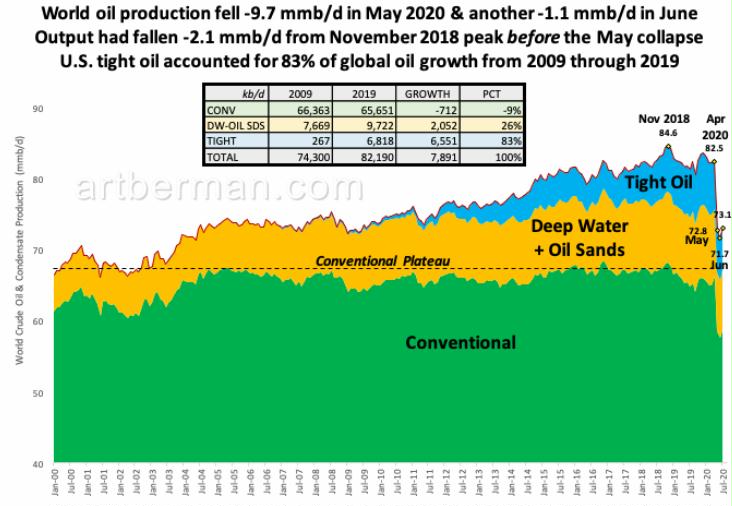

Conventional world crude oil production leveled in 2005, and peaked in 2008 at 69.5 million barrels per day (mb/d) according to Europe’s International Energy Agency (IEA 2018 p45). We get 90% of our petroleum from conventional oil.

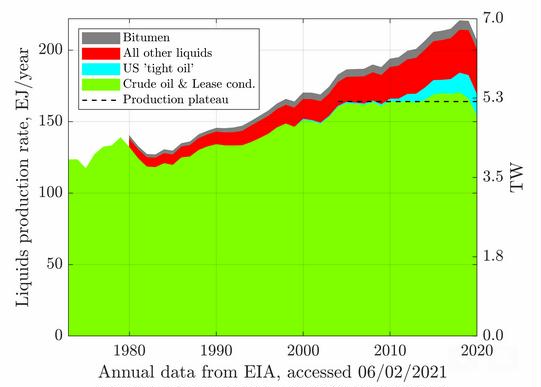

Source: Tad Patzek.

Source: Tad Patzek.

The U.S. Energy Information Agency shows global peak crude oil production in 2018 at 82.5 mb/d because they included unconventional tight oil, oil sands, and deep-sea oil.

Nor will we ever reach “peak oil demand” because heavy-duty transportation (trucks, locomotives, ships), manufacturing, the 500,000 products made out of petroleum, and natural gas fertilizer that keeps 4 billion of us are utterly dependent on fossil fuels. Even the electric grid depends on fossil fuels to provide two-thirds of electricity, and nearly all of the energy to construct wind and solar contraptions (they are ReBuildable, NOT renewable). This is explained in great detail in my latest book “Life After Fossil Fuels: A Reality Check on Alternative Energy” and previous book” When Trucks Stop Running: Energy and the Future of Transportation”

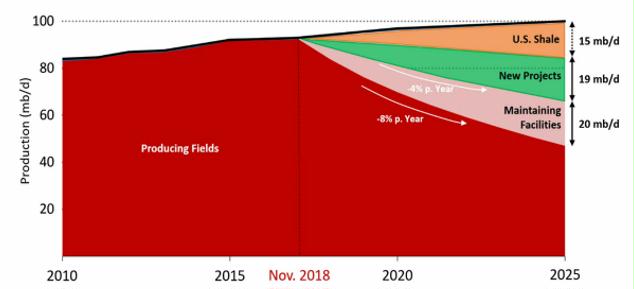

The IEA forecast a supply crunch by 2025 in their rosy and unrealistic New Policies scenario, which assumes greater efficiencies and alternative fuels and electric cars are adopted (Figure 1). By 2025, with 81% of global oil declining at up to 8% percent a year (Fustier 2016, IEA 2018), 34 mb/d of new output will be needed, and 54 mb/d if facilities aren’t maintained. That is more than three times Saudi Arabian production. The 15 mb/d of predicted U.S. shale isn’t likely — indeed, the IEA shows it declining in the mid-2020s (IEA 2018 Table 3.1).

The IEA (2018) points out that the new conventional crude projects approved over the last three years are only half the amount needed by 2025. With Covid-19, few projects are likely to begin. Oil prices have gone down so much that exploration and production investments were plummeting before Covid-19 and many fields already found are too costly to develop. Already four years of world oil consumption, 125 billion barrels, are likely to be written off by oil companies and remain in the ground (Rystad 2020, Hurst 2020).

Figure 1. Expected decline of oil production (red area) and possible stopgaps to the decline rate of 4 to 8% a year. Maintaining facilities refers to enhanced recovery from existing fields (IEA 2018). Modified figure 1.19 from IEA.

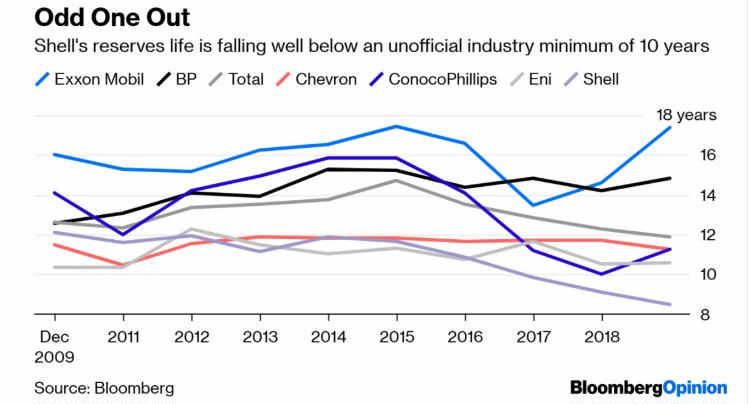

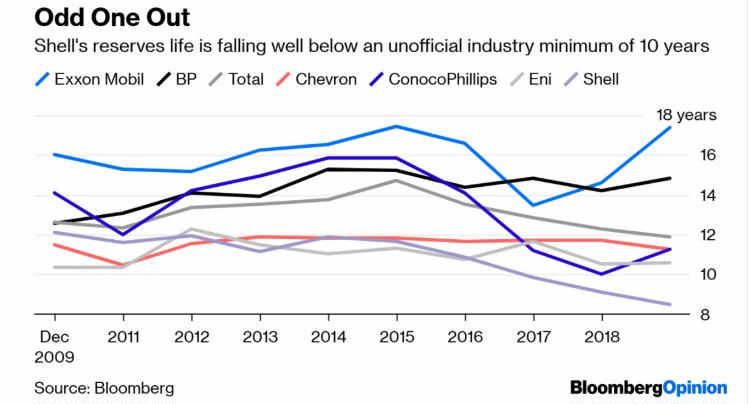

The IEA 2018 World Energy Outlook predicted an oil crunch could happen as soon as 2023. Oil supermajors are expected to have 10 years of reserve life or more, Shell is down to just 8 years.

Political shortages are as big a problem as geological depletion. At least 90% of remaining global oil is in government hands, especially Saudi Arabia and other countries in the middle east that vulnerable to war, drought, and political instability. Over two-thirds of the remaining oil is in the Middle East, and as populations keep growing there, less oil will be exported as well.

About a quarter of the remaining oil is in the arctic, and will be difficult and extremely expensive to develop due to land permafrost soils and icebergs offshore (see the posts here for details).

And don’t look to offshore oil either, many new offshore projects have even been put on hold. “Between low demand, soaring inventories, depressed prices, a global pandemic, and now, hurricane season, it seems a perfect storm is forming around the offshore oil industry. The world’s offshore oil market, responsible for 30 percent of all the world’s oil production, is facing an impossible set of challenges. With oil sitting at half the price of its yearly high, companies are struggling to rein in capital spending and are beginning to rethink the future of key projects. The crisis has pushed much of the world’s oil production onshore in favor of more flexible rigs and lower operational costs. Many firms operating offshore rigs have yet to recuperate from the last oil price collapse in 2014-2015 when prices fell from $100 to below $40, weighing on the entire industry. Offshore drillers and offshore vessel providers will generally be unable to pay their total outstanding debt of 2020 based on their cash flow from operating activities, unless they are able to make sufficient capital expenditure cuts (Kern 2020).

Watkins S (2021) The Facts Behind Saudi Arabia’s Outrageous Oil Claims. oilprice.com

Saudi Aramco’s chief executive officer, Amin Nasser, said that the company expects to boost its oil production capacity to 13 million barrels per day (bpd) by 2027 from 12 million bpd now. This claim is doubtful.

At the beginning of 1989, Saudi Arabia claimed proven oil reserves of 170 billion barrels. Only a year later, and without the discovery of any major new oil fields, the official reserves estimate had somehow increased by 51.2% to 257 billion barrels. Shortly thereafter, it increased again to 266 billion barrels or so, and in 2017 to 268.5 billion barrels. On the other side of the supply-demand equation, from 1973 to the end of last week, Saudi Arabia pumped an average of 8.162 million barrels per day of crude oil. Therefore, taking 1989 as a starting point (with 170 billion of crude oil reserves officially claimed in that year), in the subsequent 32 years Saudi Arabia has physically pumped and removed forever, a total of 95,332,160,000 barrels of crude oil. Over the same period, there has been no significant discovery of major new oil fields. Despite this, Saudi Arabia’s crude oil reserves have not gone down, but rather have actually gone up. This is a mathematical impossibility on this scale.

Next up – spare capacity. The EIA defines spare capacity very specifically as production that can be brought online within 30 days and sustained for at least 90 days. Saudi Arabia stated for decades that it had a spare capacity of between 2.0 and 2.5 million bpd. This implied – given the widely accepted (but also wrong, as highlighted above) belief that Saudi had pumped an average of around 10 million bpd for many years – that it had the capability to ramp up its production to about 12.5 million bpd in the event of unexpected disruptions elsewhere. This is almost the same level as Nasser’s most recent statement. However, as the 2014-2016 Oil Price War dragged on and reached new heights of economic devastation both for Saudi Arabia and its OPEC brothers, the Kingdom could on average produce no more than just about 10 million bpd – very rarely managing to hit above 10.5 million bpd in the two-year duration of the War.

The obvious question was a simple one: if Saudi had the ability to pump up to 12.5 million bpd then why did it not produce this to the maximum degree at this point, given that the core aim of the 2014-2016 Oil Price War was to destroy the US shale sector, crashing prices by producing as much oil as possible? The answer was very simple: it was producing the most crude oil that it could, based on its true oil production figure of around 8 million bpd (therefore an extra 2.5 million bpd equaled 10.0-10.5 million bpd, the very figure it managed just about to achieve) and not on its nonsense figure of oil production of 10 million bpd (which another 2.0-2.5 million bpd would boost to 12.0-12.5 million bpd).

Finally, crude oil production. As highlighted in the two previous paragraphs from 1973 to the end of last week, Saudi Arabia pumped an average of 8.162 million barrels per day of crude oil. Not 10 million, 11 million, 12 million, 13 million, or any other ridiculous figure that it suits the Saudis to dream up: 8.162 million barrels per day, 8.162 million barrels per day, 8.162 million barrels per day. Why does the Kingdom lie about this? Simple: without its oil power the country has no real power at all, so enormously exaggerating its crude oil reserves, spare capacity, and production figures is geared towards puffing itself up in terms of geopolitical importance. In order to obfuscate these real numbers, the Saudis have devised the semantic trickery of interchangeably switching the use of the word ‘production’ with ‘capacity’ or even ‘supply to the market’. The two sets of words do not mean the same thing at all, and the Saudis know it.

2019-11-19 The Truth About The World’s Deepest Oil Well

How deep into the ground do we have to go to tap the resources we need to keep the lights on? How deep into the ground are we able to go?

The first oil well drilled in Texas in 1866 was a little over 100 feet deep: the No 1 Isaac C. Skillern struck oil at a depth that, from today’s perspective, is ridiculously shallow.

Ten years ago, data from the Energy Information Administration shows the average depth of U.S. exploration oil wells was almost 7,800 feet. It’s safe to assume that over these past 10 years, the average well depth has only increased.

The Bertha Rogers No 1 natural gas well in the Anadarko Basin used to be the deepest in the world, at over 31,400 feet. Unfortunately, at this depth the drillers struck liquid sulfur, which put an end to plans to continue drilling.

BP’s Tiber field in the Gulf of Mexico, drilled by the infamous Deepwater Horizon, became the location for the deepest oil well. The Tiber well’s depth was more than 35,000 feet.

There is also a record-breaker in terms of water depth: Maersk Drilling’s Raya-1 well offshore Uruguay was drilled in water depths of 3,400 meters or 11,156 feet.

2019-10-27 The Biggest Oil & Gas Discoveries Of 2019

Conventional oil and gas discoveries have fallen to their lowest in 70 years. All in all, this year has seen new discoveries of nearly 8 billion barrels of oil equivalent, compared to 10 billion barrels of oil equivalent discovered last year, so only one barrel out of every six consumed is being replaced with new resources.

Not only has the pace of discovery declined, but discoveries are also in much more challenging geological venues and typically offshore, which means it could take many years just to bring new resources online.

The age of discoveries onshore is over. The future game of discovery is decidedly in deep waters.

2019-6-10 World crude production outside US and Iraq is flat since 2005

***

Rapier, R. 2019. The U.S. accounted for 98% of global oil production growth in 2018. Forbes.

Earlier this month BP released its Statistical Review of World Energy 2019. The U.S. extended its lead as the world’s top oil producer to a record 15.3 million BPD (my comment: minus 4.3 million BPD natural gas liquids, which really shouldn’t be included since they aren’t transportation fuels). In addition, the U.S. led all countries in increasing production over the previous year, with a gain of 2.18 million BPD (equal to 98% of the total of global additions),… which helped offset declines from Venezuela (-582,000 BPD), Iran (-308,000 BPD), Mexico (-156,000 BPD), Angola (-143,000 BPD), and Norway (-119,000 BPD).

Peak demand? Hardly: “the world set a new oil production record of 94.7 million BPD, which is the ninth straight year global oil demand has increased.

Matt Mushalik. 2019. World crude production outside US and Iraq is flat since 2005. crudeoilpeak.info

After 20 charts showing global oil production Matt concludes “When US shale oil peaks and Iraq can no longer increase production there will be some surprises for a complacent world which should have used the 2008 oil price shock as a warning to get away from oil – voluntarily.”

Fickling, D. 2019. Sunset for Oil Is No Longer Just Talk. Bloomberg.

An oil company that doesn’t increase its reserves eventually runs out of product to sell, so having 10 years of reserve life is traditionally considered a bare minimum for oil supermajors (for our purposes, take these to be Shell plus Exxon Mobil Corp., BP Plc, Total SA, Chevron Corp., ConocoPhillips, and Eni SpA). Shell crossed below the 10-year level all the way back in 2016, and the figure at the end of 2018 stood at just 8.5 years.

Williams, A. March 31, 2017. Down 10%, Mexico Oil Reserves Gone in 9 Years Without New Finds. Bloomberg.

Mexico’s existing oil reserves are dwindling so fast the country could go dry within nine years without new discoveries according to the National Hydrocarbons Commission, which said reserves fell 10.6% to 9.16 billion barrels in 2016, from 10.24 billion barrels a year earlier. Once the world’s third largest crude producer, Mexico’s proven reserves have declined 34% since 2013.

The decline in proven reserves is driven by record-low drilling activity the last three years. State-owned producer Petroleos Mexicanos drilled 21 wells last year, a record low, after averaging 31 per year since 2010.

Kaufman, A. C. 2016-10-26. Exxon Mobil could be on the brink of irreversible decline. Huffington Post.

Exxon Mobil Corp. may be facing “irreversible decline” as the oil giant fails to cope with low oil prices and mounting debt, a report released Wednesday found.The Texas-based company has suffered a 45% drop in revenue over the past 5 years as it bet big on drilling in oil sands, the Arctic and deep-sea sites ― decisions that proved expensive, environmentally risky and politically controversial.

Combined with a two-year plunge in oil prices, ballooning long-term debt to cover dividend payments to shareholders and an evaporating pool of cash, Exxon Mobil’s finances show “signs of significant deterioration,” according to new research from the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, a nonprofit based in Cleveland.

“Investors right now are getting less cash from Exxon than they have historically, and are likely to get less cash in the future,” Tom Sanzillo, director of finance at the IEEFA, told The Huffington Post on Wednesday. “This is going to be a much smaller company in the future, and the oil industry is going to be much smaller in the future.”

In April, Exxon Mobil was stripped of Standard & Poor’s top credit rating for the first time since the 1930s. The rating agency said it worried Exxon took on billions in debt to fund new drilling projects at a time when oil prices were high. Now, with the price of crudebelow $50 per barrel, that debt looks risky. Despite S&P specifically citing such payments in its downgrade, Exxon Mobil actually increased its dividend by 2 cents the next day.

Usually, dividends go up as a company’s stock price thrives. But shares of Exxon have trailed the S&P 500 for 10 quarters in a row, the report noted, and that’s before factoring in the risks of climate change.

Exxon Mobil is embroiled in a bevy of legal fights, notably with a handful of state attorneys general who are investigating the company for spending decades covering up the role of burning fossil fuels in global warming. The firm has repeatedly insisted such probes are politically motivated, and claimed that subpoenas seeking internal documents on climate change violate its constitutional rights.

References

Dellanoy L et al (2021) Peak oil and the low-carbon energy transition: A net-energy perspective. Applied Energy 304.

EIA (2022) International Energy Statistics. Petroleum and other liquids. Data Options. U.S. Energy Information Administration. What’s important is THE Crude oil including lease condensate because this is the segment of petroleum that is a transportation fuel, many of the others are only good for plastics, heating and non-transportation uses. 2021 isn’t available yet, here are the years before that: 2018 83,053 2019 82,340 2020 76,101

Fustier K, Gray G, Gundersen C, et al (2016) Global oil supply. Will mature field declines drive the next supply crunch? HSBC global research.

Geiger J (2022) U.S. Shale Could Peak In 2024: Energy Aspects. oilprice.com

Hurst L (2020) Oil companies wonder if looking for oil is still worth it. https://www.rigzone.com/news/wire/oil_companies_wonder_if_looking_for_oil_is_still_worth_it-17-aug-2020-163038-article/. Accessed 1 Nov 2020.

IEA (2018) International Energy Agency World Energy Outlook 2018, figures 1.19 and 3.13. International Energy Agency.

Laherrère J, Hall CAS, Bentley R (2022) How much oil remains for the world to produce? Comparing assessment methods, and separating fact from fiction. Current research in Environmental Sustainability.

Lambert JG, Hall CAS, Balogh S et al (2014) Energy, EROI and quality of life. Energy Policy 64:153–167

Kern M (2020) A Nightmare Scenario For Offshore Oil. oilprice.com

Rystad (2020) Covid-19 report. Global outbreak overview and its impact on the energy sector. Rystad Energy.

Slav I (2022) The World Is Facing A Critical Diesel Shortage. oilprice.com

Turiel A (2021) El pico del diésel: edición de 2021. The oil crash.

7 Responses to Peak diesel is near. We are running out of time