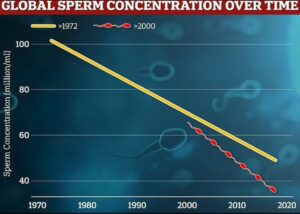

The rate sperm concentration is falling globally from samples collected from 1972 to 2000 (orange) and since 2000 (red) Source: Davies 2022

Preface. I’ve been seeing this issue in science news for years now. Scientific data has accumulated long enough to be sure that this is definitely something to worry about as the excellent article below explains. And it’s not only happening in humans, but dogs and other species too.

Perhaps the most scary paragraph is: “If the decline continues at the current rate, the median sperm count would reach zero by the mid-2040s. Within a generation, “we may lose the ability to reproduce entirely”, the magazine GQ declared in 2018.”

On the plus side, since I can’t think of a single problem that wouldn’t be helped with fewer people (less pollution, biodiversity loss, climate change, more food for everyone etc), this is the only solution that may ease the worst of the coming crash. But a shame if it leads to extinction, an enormous tragedy given that we may be the only intelligent species in our and many other galaxies (Rare Earth: why complex life is uncommon in the universe and another post with updates coming out on March 24, 2024).

Meanwhile the right wing of all religious and economic persuasions wants to eliminate abortion to have as many followers, customers, and soldiers as possible. Hmmm. Men aren’t actually necessary, women can reproduce with parthenogenesis…

Alice Friedemann www.energyskeptic.com Author of Life After Fossil Fuels: A Reality Check on Alternative Energy; When Trucks Stop Running: Energy and the Future of Transportation”, Barriers to Making Algal Biofuels, & “Crunch! Whole Grain Artisan Chips and Crackers”. Women in ecology Podcasts: WGBH, Financial Sense, Jore, Planet: Critical, Crazy Town, Collapse Chronicles, Derrick Jensen, Practical Prepping, Kunstler 253 &278, Peak Prosperity, Index of best energyskeptic posts

***

Robson D (2024) Avoiding spermageddon. Sperm decline is accelerating across the world. New Scientist.

By the 1990s, the issue started catching considerably more scientific attention, although some researchers were still sceptical. They blamed differences in techniques, or the fact that studies were mostly on men already having treatment for infertility. Such doubts are now shrinking. “There is a huge body of scientific evidence showing this decline,” says Albert Salas-Huetos at the University of Rovira i Virgili in Spain.

For researchers like Salas-Huetos, the big question is no longer whether this so-called “spermageddon” is really happening, but why and what to do about it. Studies are beginning to shed light on environmental toxins that may be to blame, as well as other lifestyle factors contributing to the problem. With a better idea of the prime suspects, we may finally be able to put the brakes on this trend, or even reverse it.

Sperm count decline

Globally, around 1 in 6 people have trouble conceiving, according to a recent report by the World Health Organization. There are many potential causes, but between 30 and 50 per cent of cases are linked to problems with the quantity and quality of semen. It may be that the total number of sperm is simply too low, or that the tadpole-like cells struggle to swim – a problem called poor motility – which vastly reduces the chance that sperm can reach the ovum, or egg cell. Some may have genetic defects within the chromosomes they are carrying, known as DNA fragmentation.

Shanna Swan, a reproductive epidemiologist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, has led many of the most eye-catching studies. Her interest began in the 1990s, when she was asked by the US National Academy of Sciences to independently review a study from Denmark reporting rapid sperm decline. Swan was initially sceptical: she suspected that the researchers might have missed some confounding factor in their analysis. When she crunched the data, however, she kept finding the same rate of decline predicted by the Danish team. “We didn’t change the slope at all – not down to the second decimal place,” says Swan.

Her conviction has only increased over the subsequent decades. In 2017, she and her colleagues published a meta-analysis that considered data from 185 studies of more than 42,000 men between 1973 and 2011, making it the largest of its kind. Swan’s team examined two different measures: the concentration of sperm in a millilitre of semen and the total number of sperm in the sample. In North America, Europe, Australia and New Zealand, both figures seemed to be falling at a rate of around 1.5 per cent per year on average, resulting in a 50 to 60 per cent drop over the whole period.

If the decline continued at this rate, the median sperm count would reach zero by the mid-2040s. Within a generation, “we may lose the ability to reproduce entirely”, the magazine GQ declared in 2018.

At the time of this analysis, Swan and her team didn’t have enough data to draw strong conclusions about sperm counts in the rest of the world. They have now filled this gap in knowledge with additional data from South America, Asia and Africa. The ensuing paper, published in 2023, reported a decline on every continent studied.

Such studies do have some limitations. Meta-analyses can be skewed by differences between datasets. Counting sperm is a fiddly job and the technology used to do it has changed over the years, which may bias the reported numbers. Nevertheless, the latest studies control for this potential bias and the pattern remains, says Richard Lea at the University of Nottingham, UK.

Then there is comparative evidence from man’s best friend. Vets regularly test stud dogs’ sperm quality, which is carefully recorded for controlled breeding programmes. This provides an excellent source of data to study potential changes in dog fertility over time. Lea and his team recently analysed data from a lab measuring dogs’ sperm motility between 1988 and 2014. Crucially, the lab’s methods had remained the same across the 26-year period, eliminating any possibility that methodological changes would bias the results. “The decline in sperm quality we saw in dogs parallels that seen in humans,” says Lea.

It isn’t yet clear how important a decline in sperm is for overall fecundity. We see large variation in sperm count between men who don’t have any significant health issues, but the absolute figures don’t seem to make a big difference to the chances of conception until they dip below a very low threshold. “And all of the average sperm counts are still above the level required for fertility,” says Marion Boulicault at the University of Edinburgh, UK. It is possible, she says, that we are simply witnessing natural variability within a healthy range, rather than an endless decline.

Even so, scientists investigating the trend are concerned with the speed of the decline, which doesn’t show signs of slowing. Indeed, Swan’s research suggests it may even be accelerating. “If you see a 50 per cent decline in 50 years, that sets off an alarm,” says Salas-Huetos.

Lea, meanwhile, points out that the reduced sperm counts coincide with a higher prevalence of numerous other global reproductive issues. Increasing numbers of children are being born with genital malformations, for instance, and rates of testicular cancer in young men have also been on the rise. “That data’s really robust,” he says.

What causes sperm decline?

The suggestion is that there may be some underlying environmental or lifestyle factors driving all these different trends. This is now the primary area of interest for Swan, and she says there is a growing body of evidence that chemicals may play a major causal role.

For decades, pollutants called endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), have been on our radar as the prime suspects behind infertility in men and women. These are thought to interfere with hormonal signalling and include common chemicals found in some plastics and pesticides.

The drop in sperm count today could be the result of EDC exposure during the earliest months of development. We know that fetal growth is, in part, governed by levels of sex hormones, and EDCs could upset this process. Animal studies have shown that exposure to EDCs during critical windows of fetal development can result in genital malformations and a reduced ability for males to produce sperm later in life. Likewise, research examining people who have been exposed to EDCs through their occupation has also shown links between exposure and decreases in sperm count, viability and motility.

Environmental hazards

Common pollutants can make their way into the testes through the diet and the surrounding environment. To test the effects that this may be having on sperm quality, Lea’s team recently incubated samples of dog and human sperm with different concentrations of diethylhexyl phthalate and polychlorinated biphenyl 153. The former is used in cosmetics, personal hygiene products and furniture materials. The latter, once widely used in industrial products such as paint and rubber, was banned internationally in 2001 after being deemed potentially carcinogenic, but it persists in soil, water and building materials. The result was reduced motility and higher rates of DNA fragmentation in sperm. Swan’s research has also shown a relationship between phthalates and low sperm count. Other studies have found similar results for bisphenol A, or BPA,a chemical used to make rigid plastics, including food storage containers and refillable drinks bottles. For instance, one showed that men who were occupationally exposed to BPA were more likely to have a reduced libido, erectile dysfunction and decreased sperm quality.

Although the UK’s Food Standards Agency says that the levels of BPA typically detected in food aren’t considered harmful, it has banned its use in items intended for infants. The agency says that it is reviewing the latest evidence and may revise restrictions on BPA in the future.

In any case, some manufacturers have replaced BPA with other chemicals, such as bisphenol F (BPF) and bisphenol S (BPS). A recent study analysed the effect of BPA on bulls’ sperm, comparing it with that of BPF and BPS. It found that BPA was the worst offender, but BPF also decreased sperm motility, energy and capacity to fertilise an egg. BPS didn’t have any significant effects.

Diet and sperm count

It isn’t just environmental toxins that are in the crosshairs. The role of diet in sperm decline has also come under scrutiny. From 1980 to 2019, the number of men and boys in England aged 16 and over who were obese rose from 6 per cent to 27 per cent, with similar trends across many other countries.

Multiple studies have found that men who are overweight produce less semen, have a lower overall sperm count and have reduced sperm motility. This, in turn, can influence the outcome of fertility treatments. In 2022, a team of researchers, including Salas-Huetos, tracked the success rates of 176 couples visiting Massachusetts General Hospital Fertility Center and measured the sperm counts of the men. A 5-centimetre increase in a man’s waist circumference was associated with a 6.3 per cent drop in sperm concentration and a 9 per cent reduction in the chances of a live birth for each cycle of treatment.

Salas-Huetos suggests that inflammation is to blame. Excess body fat produces inflammatory molecules that can wreak havoc on other tissues, including those of the genitals, and reduce the production of testosterone. “The hormonal [balance] that you have to maintain to produce sperm – it is totally disturbed,” he says.

The nutritional quality of food may also be key. A 2019 study found that men who regularly consume fruits, vegetables, nuts and fish have higher sperm concentrations with greater motility than those with less balanced diets. These foods tend to be high in antioxidant compounds, which help to neutralise rogue molecules called free radicals. The production of semen seems to be particularly sensitive to this form of free radical stress, so any nutrients that mop up these molecules may contribute to sperm health. The presence of omega-3 fatty acids – which are known antioxidants with anti-inflammatory properties – appears to be particularly important in predicting sperm quality, according to one 2020 study. High sugar consumption, in contrast, is linked to reduced sperm quality.

Since the covid-19 pandemic began, more attention has also been given to the impact of viruses on sperm. Several studies have shown how infection with covid-19 reduces sperm counts and motility, potentially due to the virus interfering with the later stages of sperm development, or fever upsetting the delicate homeostasis needed to grow healthy sperm.

This decline usually reverses as the infection wanes, although one study of men visiting a fertility centre showed that a subset still had decreased sperm health more than three months after covid-19 infection.

How to improve your sperm count

There is some good news. If obesity, diet and infection are affecting sperm production, lifestyle interventions and vaccinations may be able to offset a fertility crisis – and a handful of randomised clinical trials over the past few years already provide grounds for optimism.

Emil Andersen at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark and his colleagues asked 56 men who were obese to reduce their calorie intake to just 800 calories a day for eight weeks. Publishing their results in 2022, Andersen and his team found that participants lost 16.5 kilograms on average, and their sperm count increased by more than 40 per cent. Tracking the men for a year after the diet showed that these improvements continued for as long as they kept the weight off, but disappeared if they regained the lost kilos.

Salas-Huetos and his colleagues, meanwhile, examined the benefits of adding 60 grams per day of walnuts, almonds and hazelnuts to men’s diets for 14 weeks. These nuts are all high in antioxidants, which the team suspected would help reduce genetic damage to sperm. Sure enough, the men adhering to this programme showed increased sperm counts and motility, and reduced DNA fragmentation, while those continuing with their standard diet didn’t show any improvement.

There may be many different routes to reaping these benefits. An Italian study from 2022 offered 137 men an individualised regime emphasising increased physical activity and an adherence to the “Mediterranean diet“, which incorporates many of the components thought to benefit fertility. After four months, they experienced significant improvements in sperm quantity and quality compared with people in the control group

The effect of exercise on your sperm count

Given that diet and exercise often go hand in hand when it comes to lifestyle interventions and good health, you might think that exercise would be firmly linked to better sperm. In reality, however, it isn’t so straightforward.

Small studies have shown some increases in the health of sperm with moderate exercise, such as 30 minutes of cardio, three times a week. Likewise, a recent study showed that men who lift heavy objects at work had a 44 per cent higher sperm count compared with those who had less physical jobs. They also had higher testosterone and oestrogen levels, which have been associated with better general hormonal balance. However, other studies suggest that you shouldn’t overdo it. For instance, sperm health decreases after a period of rigorous exercise, such as trekking up a high mountain for 6 to 8 hours a day for five days, or after intensive cycling training for 16 weeks. A larger study of cyclists found no link with fertility (see “What causes sperm decline? Fact and fiction”, below), but more evidence is needed to say for sure.

So, where does that leave us? “If you think of what a doctor would tell you to change to improve your heart health, you’re also going to improve your sperm health,” says Swan.

It has been 50 years since Nelson and Bunge first announced their findings. While today’s researchers may still debate the specific causes, consequences and cures of sperm decline, they are united in one opinion: the urgent need for a greater understanding.

“It deserves a lot of attention,” says Boulicault. “Reproductive health is a really important part of people’s lives and that means that the way we do the science has to be extra vigilant and robust.”

Swan compares it to the climate crisis. “We’re following the same path,” she says. “You have the first warnings, then you have the big wave of denial, then you have more people agreeing that it is getting worse.”

Next comes the hard part: taking action. The clock is ticking – and future generations may judge us for the decisions we make today.

References

Davies J (2022) Spermageddon! Men’s sperm rates have more than HALVED since the 1970s as experts warn trend could ‘threaten mankind’s survival’. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-11429551/Mens-sperm-rates-halved-1970s.html