Preface. For many people, it’s comforting to know that about 25% of remaining oil and gas reserves (we have the know-how and economics to get it) and resources (beyond our technical and/or monetary capability) are in the arctic. They assume we’ll get this oil and gas when we need to, and delay oil shortages for a decade or more.

But it is difficult to drill for oil or gas and mine coal in permafrost, which buckles roads, airports, buildings, pipelines, and any other structures on top. Offshore icebergs can mow down oil and gas platforms. Much of this this oil and gas will turn out to be resources.

Although there is certainly oil to be found on the North slope, this is an almost gravel free zone. Yet gravel is essential to build roads, runways, housing and other major infrastructure on top of the permafrost, and to stabilize existing infrastructure as climate change melts ever more permafrost that was once frozen solid year round. It is also needed for seawalls to protect oil drilling projects and native villages from coastal erosion.

The two projects in the north slope, Willow and Pikka, expected to be done by 2032 are near Nuiqsut, where there are gravel mines, and also as far north (near Prudhoe Bay) as you can get where the permafrost is still frozen year round. Permafrost problems in Willow have already happened though, 7.2 million cubic feet of natural gas were released after ConocoPhillips injected drilling fluids deep underground, and the heat thawed the permafrost layer to a depth of 1,000 feet that allowed the gas to reach the surface (Federman 2022).

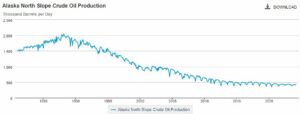

Otherwise, North slope gravel would cost as much as $800 per cubic yard, enough to cover about 50 square feet, while in Anchorage the cost is just $15. If these two projects succeed that will also keep the Alaskan pipeline open, which will freeze up if too little oil is flowing, and Prudhoe Bay production has fallen so much since 1981 that it is getting close to the level that will freeze up the pipeline.

Source: EIA (2024) Alaska North Slope Crude oil production. U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Today the pipeline carries 4% of America’s crude oil. Though in 2021 a thaw of permafrost caused an 810-foot section of the pipeline to shift, twisting several of the braces holding the pipeline up (Hasemyer 2021), and as climate change continues, likely to happen more often in the future.

Russia’s thawing permafrost costs them about $2.3 billion a year (Fedorinova 2019).

The cost and energy of production in permafrost may mean that reserves are much less than estimated since they aren’t economically feasible, and perhaps even technically as permafrost melting grows worse.

Permafrost is ground that has remained completely frozen for at least two years straight and is found beneath nearly 85 percent of Alaska. In the last few decades, permafrost temperatures there have warmed as much as 3.5 degrees Fahrenheit. The state’s average temperature is projected to increase 2 to 4 degrees more by the middle of the century, and a study published in the journal Nature Climate Change projects that with every 2 degree increase in temperature, 1.5 million square miles of permafrost could be lost to thawing.

Alice Friedemann www.energyskeptic.com Author of Life After Fossil Fuels: A Reality Check on Alternative Energy; When Trucks Stop Running: Energy and the Future of Transportation”, Barriers to Making Algal Biofuels, & “Crunch! Whole Grain Artisan Chips and Crackers”. Women in ecology Podcasts: WGBH, Financial Sense, Jore, Planet: Critical, Crazy Town, Collapse Chronicles, Derrick Jensen, Practical Prepping, Kunstler 253 &278, Peak Prosperity, Index of best energyskeptic posts

* * *

Schwing E (2024) Alaska is short on gravel and long on development projects. The Atlantic.

Alaska’s North Slope is rich in oil, gas, minerals. But one important thing is lacking: Rocks. “Yes, gravel is a precious commodity on the North Slope,” said Jeff Currey, an engineer with the state’s Department of Transportation and Public Facilities who works in the agency’s Northern Region Materials Section. For decades, Currey said, the state has been searching for gravel all over the North Slope, with limited success.

Gravel is essential for all kinds of long-term development: building projects, road construction, runways and other major infrastructure.

Lee, J. 2019. Why Vladimir Putin Suddenly Believes in Global Warming. Russia was happy that global warming opened up Arctic oil, but the melting of permafrost poses a huge threat to its hydrocarbon heartlands. Bloomberg.

Until now, climate change has been seen as a “good thing” for Russia — at least in part. Warming waters have opened up the Northern Sea Route across the top of the country and made it practical, if not necessarily economic, to search for and exploit oil and gas resources beneath the Arctic seas. Who remembers the Shtokman gas project?

Yet the warming that is opening up the Arctic seas may be starting to have a less beneficial effect on the frozen landmass of northern Russia, the heartland of the country’s oil and gas development and production.

Areas of discontinuous permafrost could see a 50-75% drop in load bearing capacity by 2015-25 compared with 1965-75 [my comment: which can damage or destroy existing pipelines and other infrastructure].

“Permafrost is undergoing rapid change,” says the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate report adopted by the IPCC last week. The changes threaten the “structural stability and functional capacities” of oil industry infrastructure, the authors warn. The greatest risks occur in areas with high ground-ice content and frost-susceptible sediments. Russia’s Yamal Peninsula — home to two of Russia’s biggest new gas projects (Bovanenkovo and Yamal LNG) and the Novy Port oil development — fits that bill.

The problem is bigger than those three projects, though. Some “45% of the oil and natural gas production fields in the Russian Arctic are located in the highest hazard zone,” according to the IPCC report.

The top few meters of the permafrost, the so-called active layer, freezes and thaws as the seasons change, becoming unstable during warmer months. Developers account for this by making sure their foundations are deep enough to support their infrastructure: including roads, railways, houses, processing plants and pipelines. But climate change is causing that active layer to deepen, which means the ground loses its ability to support the things built upon it. The loss of bearing capacity is dramatic and it’s already well under way.

Foundations in the permafrost regions can no longer bear the loads they did as recently as the 1980s, according to a 2017 report by the Arctic Council’s Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Program. At Noviy Port the bearing capacity of foundations declined more than 20% between the 1980s and the first decade of this century.

On the Yamal Peninsula the ground’s bearing capacity is forecast to fall by 25%-50% on average in the 2015-2025 period, when compared with the years 1965-1975. Further south, in an area that includes Urengoy (the world’s second-largest natural gas field) and much of Russia’s older West Siberian gas production, the soil could lose 50-75% of its bearing capacity, according to AMAP.

While the impact of retreating permafrost on Russia’s new Arctic oil and gas developments can be mitigated, it adds to the price of the projects in an already high-cost environment. For older infrastructure the problems are worse. Gas production at the Bovanenkovo field on the Yamal Peninsula is expected to reach 140 billion cubic meters a year — more than Norway’s entire production — but it “has seen a recent increase in landslides related to thawing permafrost,” says the AMAP.

NRC. 2013. Abrupt Impacts of Climate Change: Anticipating surprises. National Research Council, National Academies of Sciences press.

Permafrost, or permanently frozen ground, is ubiquitous around the Arctic and subArctic latitudes and the continental interiors of eastern Siberia and Canada, the Tibetan Plateau and alpine areas. As such, it is a substrate upon which numerous pipelines, buildings, roads and other infrastructure have (or could be) built, so long as these structures are properly designed to not thaw the underlying permafrost. For areas underlain by ice-rich permafrost, severe damage to permanent infrastructure can result from settlement of the ground surface as the permafrost thaws (Nelson

Over the past 40 years, significant losses (>20%) in ground load-bearing capacity have been computed for large Arctic population and industrial centers, with the largest decrease to date observed in the Russian city of Nadym where bearing capacity has fallen by more than 40%. Numerous structures have become unsafe in Siberian cities, where the percentage of dangerous buildings ranges from at least 10% to as high as 80% of building stock in Norilsk, Dikson, Amderma, Pevek, Dudina, Tiksi, Magadan, Chita, and Vorkuta.

The second way in which milder winters and/or deeper snowfall reduce human access to cold landscapes is through reduced viability of winter roads (also called ice roads, snow roads, seasonal roads, or temporary roads). Like permafrost, winter roads are negatively impacted by milder winters and/or deeper snowfall. However, the geographic range of their use is much larger, extending to seasonally frozen land and water surfaces well south of the permafrost limit. They are most important in Alaska, Canada, Russia, and Sweden, but also used to a lesser extent (mainly river and lake crossings) in Finland, Estonia, Norway, and the northern US states. These are seasonal features, used only in winter when the ground and/or water surfaces freeze sufficiently hard to support a given vehicular weight. They are critically important for trucking, construction, resource exploration, community resupply and other human activities in remote areas. Because the construction cost to build a winter road is <1% that of a permanent road, winter roads enable commercial activity in remote northern areas that would otherwise be uneconomic. Since the 1970s, winter road season lengths on the Alaskan North Slope have declined from more than 200 days/year to just over 100 days/year. Based on climate model projections, the world’s eight Arctic countries are all projected to lose significant land areas of up to 82% that currently possess climates suitable for winter road construction, with Canada (400,000km2/154,400 square miles) and Russia (618,000km2/238,600 square miles) experiencing the greatest losses in absolute land area terms

Although the prospect of ocean trans-Arctic routes materializing has attracted considerable media attention, it is important to point out that these routes would operate only in summer, and numerous other non-climatic factors remain to discourage trans-Arctic shipping including lack of services, infrastructure, and navigation control, poor charts, high insurance and escort costs, unknown competitive response of the Suez and Panama Canals, and other economic factors

Greg Quinn. August 2, 2016. Climate Change Is Hell on Alaska’s Formerly Frozen Highways A critical artery is threatened by thawing permafrost. Bloomberg.

For seven decades, the Alaska Highway has mesmerized adventure-seeking travelers. In one breathtaking stretch through the Yukon, glacier lakes and rivers snake through aspen forests and rugged mountains that climb into the clouds.

In recent years, though, a new sight has been drawing motorists’ attention, too, one they can spot just a few feet from their cars’ tires. Bumps and cracks have scarred huge swathes of the road, with some fissures so deep a grown man can jump in and walk through them. Scientists say they’re the crystal-clear manifestation that permafrost — slabs of ice and sediment just beneath the Earth’s surface in colder climes — is thawing as global temperatures keep rising.

In some parts of the 1,387-mile (2,232 kilometer) highway, the shifting is so pronounced, it has buckled parts of the asphalt. Caution flags warn drivers to slow down, while engineers are hard at work concocting seemingly improbable solutions: inserting plastic cooling tubes or insulation sheets, using lighter-colored asphalt or adding layers of soccer-ball sized rocks — fixes that are financially and logistically daunting.

“It’s the single biggest geotechnical problem we have,” said Jeff Currey, materials engineer for the northern region of Alaska’s Department of Transportation. “The Romans built roads 2,000 years ago that people are still using. On the other hand, we have built roads that within a year or two, without any maintenance, look like a roller coaster because they are built over thaw-unstable permafrost.

At the time of its construction, the highway was a show of American ingenuity and determination during World War II. In March 1942, just months after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, the U.S. Army hastily began to build a road linking Alaska, another exposed Pacific outpost, through Canada to the lower 48 states. Seven months later it was opened, providing a key supply line in case of invasion.

Today the highway serves as the main artery connecting the “Last Frontier” with Canada and the northwestern U.S., bringing tourists to Alaska cruise ships; food, supplies and medicine to remote towns; and equipment to oil fields and mines that are the region’s lifeblood.

Judy Gagnon, a 67-year-old trucker, has driven Canada’s roads since the early 1970s and said she’s seeing “more pieces fall apart.” Some damage is regular wear and tear, but “they are having trouble maintaining the road bed, because you have the permafrost underneath, and then you have it melting and it’s sinking.

The highway’s dark surface absorbs sunlight while the shoulders trap water and snow that act like a warm blanket. The heat breaks down the permafrost (soil, rock or sediment frozen for at least two consecutive years). Annual repair costs for one section that runs through the Yukon are $22,900 per kilometer, seven times the average, according to a territorial government report.

Thawing also threatens airport runways, buildings, animal-migration patterns and energy pipelines. It’s a problem outside North America, too. More than 600 scientists from nations including the U.S., Canada, Russia, China, Sweden and Argentina, attended an international permafrost conference in June.

The Alaska Highway challenged its original builders seven decades ago by swallowing up trucks. Any digging caused some terrain to thaw unless extra layers of logs and gravel were installed on top to ensure that “the frost was permanently locked in,” according to a 1944 U.S. War Department film.

Today’s engineers don’t assume permafrost will remain stable, even with modern insulation. Some roads being built now may become lost causes, requiring new bridges or detours, if global warming exceeds estimates in upgraded building standards.

“There are so few roads, and there is no redundancy, so every road is critical,” Currey said. “A detour is possible, but the detour might be 700 miles.

Forty-three percent of a 124-mile stretch between Alaska and Whitehorse, the Yukon capital, is “highly vulnerable to permafrost thaw,” according to a report co-authored by Fabrice Calmels, a researcher at Yukon College.

“It’s like taking five stories out of a 10-story building,” he said in an interview.

One solution is to keep heat away by building thicker embankments with larger gravel and rocks that help circulate cooler air, or by adding layers of insulation such as foam. More expensive options include installing pipes to vent out warmth. Some vents, called thermosyphons, are tubes, often filled with liquid carbon dioxide, that use a cycle of evaporation and condensation to take advantage of cooler air temperatures. These work if the difference above and below ground is at least 1 degree Celsius.

The key is creating infrastructure that’s “resilient” to future changes, said Paul Murchison, director of transportation engineering at the Yukon Department of Highways and Public Works.

Mark Carney, governor of the Bank of England, and Canada’s Environment and Climate Change Minister Catherine McKenna stressed the urgency of the problem at a July 15 discussion on global warming. McKenna gave a grim update on Carney’s birthplace in the Northwest Territories, just east of the Yukon.

“Communities are unable to reach each other, it’s harder to get goods there,” she told attendees in Toronto. Thawing permafrost isn’t “just an inconvenience, folks; it’s a change in the way of life.”

REFERENCES

Federman A (2022) Unstable Ground How thawing permafrost threatens a Biden-supported plan to drill in Alaska’s Arctic. Grist.

Fedorinova, Y (2019) Russia’s Thawing Permafrost May Cost Economy $2.3 Billion a Year. Bloomberg

Hasemyer D (2021) Trouble in Alaska? Massive oil pipeline is threatened by thawing permafrost. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/trouble-alaska-massive-oil-pipeline-threatened-thawing-permafrost-n1273589