Preface. The conveyor belt (AMOC: Atlantic meridional overturning circulation) may be slowing down. If it stops, floods, increased sea level rise, and disturbed weather systems.

Until recently the IPCC and other scientists didn’t think this might happen until 2300 or so, but the latest research shows that it could happen much sooner and more suddenly than expected.

Alice Friedemann www.energyskeptic.com Author of Life After Fossil Fuels: A Reality Check on Alternative Energy; When Trucks Stop Running: Energy and the Future of Transportation”, Barriers to Making Algal Biofuels, & “Crunch! Whole Grain Artisan Chips and Crackers”. Women in ecology Podcasts: WGBH, Financial Sense, Jore, Planet: Critical, Crazy Town, Collapse Chronicles, Derrick Jensen, Practical Prepping, Kunstler 253 &278, Peak Prosperity, Index of best energyskeptic posts

* * *

Watts J (2024) Atlantic Ocean circulation nearing ‘devastating’ tipping point, study finds. The Guardian.

Collapse in system of currents that helps regulate global climate would be at such speed that adaptation would be impossible. Sea levels in the Atlantic would rise by a metre in some regions, inundating many coastal cities. The wet and dry seasons in the Amazon would flip, potentially pushing the already weakened rainforest past its own tipping point. Temperatures around the world would fluctuate far more erratically. The southern hemisphere would become warmer. Europe would cool dramatically and have less rainfall. While this might sound appealing compared with the current heating trend, the changes would hit 10 times faster than now, making adaptation almost impossible.

“What surprised us was the rate at which tipping occurs,” said the paper’s lead author, René van Westen, of Utrecht University. “It will be devastating.”

He said there was not yet enough data to say whether this would occur in the next year or in the coming century, but when it happens, the changes are irreversible on human timescales.

The circulation of the Atlantic Ocean is heading towards a tipping point that is “bad news for the climate system and humanity”, a study has found.

The scientists behind the research said they were shocked at the forecast speed of collapse once the point is reached, although they said it was not yet possible to predict how soon that would happen.

Using computer models and past data, the researchers developed an early warning indicator for the breakdown of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (Amoc), a vast system of ocean currents that is a key component in global climate regulation.

They found Amoc is already on track towards an abrupt shift, which has not happened for more than 10,000 years and would have dire implications for large parts of the world.

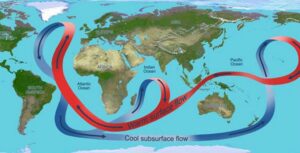

Amoc, which encompasses part of the Gulf Stream and other powerful currents, is a marine conveyer belt that carries heat, carbon and nutrients from the tropics towards the Arctic Circle, where it cools and sinks into the deep ocean. This churning helps to distribute energy around the Earth and modulates the impact of human-caused global heating.

But the system is being eroded by the faster-than-expected melt-off of Greenland’s glaciers and Arctic ice sheets, which pours freshwater into the sea and obstructs the sinking of saltier, warmer water from the south.

Amoc has declined 15% since 1950 and is in its weakest state in more than a millennium, according to previous research that prompted speculation about an approaching collapse.

The new paper, published in Science Advances, has broken new ground by looking for warning signs in the salinity levels at the southern extent of the Atlantic Ocean between Cape Town and Buenos Aires. Simulating changes over a period of 2,000 years on computer models of the global climate, it found a slow decline can lead to a sudden collapse over less than 100 years, with calamitous consequences.

The paper said the results provided a “clear answer” about whether such an abrupt shift was possible: “This is bad news for the climate system and humanity as up till now one could think that Amoc tipping was only a theoretical concept and tipping would disappear as soon as the full climate system, with all its additional feedbacks, was considered.”

Katz, C. 2019. Why is an ocean current critical to world weather losing steam? Scientists search the Arctic for answers. National Geographic.

Fram Strait and the waters to the south, in the Greenland, Norwegian, and Irminger seas, make up the control room of a global “conveyor belt” of currents that stretches the length of the planet. Only in this region and one other, in the Antarctic, does water at the sea surface become heavy enough—dense with cold and salt—to sink all the way to the seafloor and race downhill along the deepening ocean bottom. That sinking powers the conveyor, known as the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation, or AMOC—which in turn regulates temperatures and weather around the world.

A new report warns that the AMOC is one of nine critical climate systems that greenhouse-gas-fueled warming is actively pushing toward a tipping point. Crossing that threshold in one of these systems could trigger rapid and irreversible changes that drive other systems over the edge—leading to a global tipping cascade with catastrophic consequences for the planet. The analysis, released last week in Nature by an international group of leading climate scientists, says the tipping point risks are greater than most of us realize.

The AMOC conveyor belt may already be showing signs of sputtering as a result. A network of ocean probes across the mid-Atlantic, between the Bahamas and Africa, has recorded a 15 percent drop in the current’s flow over the past decade. A recent modeling study suggests that the slowdown began a half-century ago as planet-warming carbon emissions started to soar. The IPCC, projects that the conveyor will weaken as much as a third by 2100 if emissions continue at their present rate. An enfeebled AMOC could trigger a host of changes, including floods, increased sea level rise, and disturbed weather systems.

Waters east of Greenland are getting not only warmer but also less salty. These melting Greenland glaciers, melting sea ice in the Arctic, and rivers swollen by increased precipitation in Siberia have all contributed to a large flush of fresh water into the Fram Strait—a 60 percent increase over the first half of this decade.

Whether those forces are the cause of the conveyor’s current sluggishness isn’t certain. But at some point, if the water here gets too fresh, or too warm, or especially both, it will become too light to sink, say de Steur and other ocean scientists—jamming the works of one of the most fundamental forces in the global climate system. Temperatures in the polar water flowing into the Fram Strait have climbed nearly 1 degree F over the past 17 years, while the Atlantic water has warmed nearly half a degree. If the trend continues, it could dampen deepwater formation and throttle the conveyor belt’s engine just like freshening will.

Other key components of Earth’s climate works that may be heading toward a tipping point include summer sea ice, which models predict will disappear as early as 2036, permafrost, now rapidly thawing across wide swaths of the Arctic, the vast Greenland ice sheet, the Amazon rain forest, and more.

So far there’s been no change in the deepwater formation. But the warming and freshening she has observed here on past voyages are worrisome, and if things continue as they are, at some point it’s going to have an impact.

Historical climate models find that the conveyor belt has slowed significantly in recent decades. And paleoclimate evidence shows the AMOC is currently the weakest it’s been in at least a millennium. The system has been slowing for at least 50 years—in line with the rise in humans’ carbon output.

The recent IPCC report on climate change in oceans projects that, while the AMOC will weaken substantially during this century, a collapse by 2100 is unlikely. However, at our current rate of carbon output, its models give even odds of a shutdown by 2300.

An abrupt brake on the current around 950,000 years ago sent the planet into a long series of ice ages. More recently, Europe was plunged into a 2,000-year cold spell known as the Younger Dryas around 13,000 years ago, after the current sharply weakened. Although it’s not certain what caused those conveyor breakdowns, melting ice sheets are believed to have played a major role.

Even short of a shutdown, the effects of weakening ocean circulation would be felt around the globe. Because the Gulf Stream warms Northern Europe by as much as 10 degrees F, a drop in the heat flowing north would make European winters colder.

The changes in the ocean’s heat uptake and transport would make the South Atlantic hotter, shifting the bulk of the planet’s heat southward and disrupting monsoon cycles vital to Asian and South American crops, according to the IPCC.

Floods and droughts would increase on both sides of the Atlantic, along with more frequent hurricanes along the southeastern United States and Gulf of Mexico. A backed-up Gulf Stream could raise sea levels along the U.S. East Coast, driving more warm water—and possibly steamier temperatures—ashore.

Marine ecosystems and fisheries would suffer. On top of that, muddled ocean circulation could knock the already wobbly jet stream further off kilter, triggering more summer heatwaves and winter cold snaps across North America and Europe.