Preface. The lack of permanent geological storage of nuclear waste will be yet another nightmare for those living after fossils have declined and civilizations go back to biomass fuels and muscle power. They will already be dealing with heat making parts of the planet unlivable, rising sea levels, floods, and dam failures that release hazardous chemical and nuclear waste, depleted aquifers and topsoil, natural disasters, wars, mass migrations, and death by a thousand other cuts.

Nuclear waste needs to be stored for a minimum of hundreds of thousands of years, and ideally a million years or more. But it is highly unlikely that congress will ever create a permanent site before energy decline, despite the fact that not doing so NOW is endangering us all: A Nuclear spent fuel fire at Peach Bottom in Pennsylvania could force 18 million people to evacuate.

Here is some brief history and context from my next book Showstoppers about nuclear waste, followed by excerpts from the 2013 Nuclear Waste Administration Act S1240.

The NAS (2022) report “Merits and Viability of Different Nuclear Fuel Cycles & Technology Options and the Waste Aspects of Advanced Nuclear Reactors” mentions nuclear waste 1600 times. Their main recommendation for Congress is that they create a new agency not subject to political whims or budget cuts to create geological storage of high-level nuclear waste with public and political approval (GAO 2021, NAS 2022, Mcfarlane et al 2023).

Good luck with that! Been there done that. In 2012 Senate Bill S3469 “The Nuclear Waste Administration Act” (NWAA): was introduced to create an independent agency “for the permanent disposal of nuclear waste, including the siting, construction, and operation of additional repositories” and died in committee. Also in 2012 the Obama Administration established the Blue Ribbon Commission on America’s Nuclear Future (Blue Ribbon Commission on America’s Nuclear Future), which recommended that a new, “single-purpose organization” be given the authority and resources to promptly begin developing one or more nuclear waste repositories and consolidated storage facilities.” Didn’t happen. The NWAA was revived in 2013 as Bill S1240 and died in committee, revived again in 2015 as S854 and died, revived in 2019 as S1234 and died in committee. The Trump Administration included funds to restart Yucca Mountain licensing in its FY2018, FY2019, and FY2020 budget submissions to Congress, none were enacted nor have funds been sought by the Biden Administration. And many more bills as well, read the sad history in the 2021 Civilian Nuclear Waste Disposal RL33461 Congressional Research Service report.

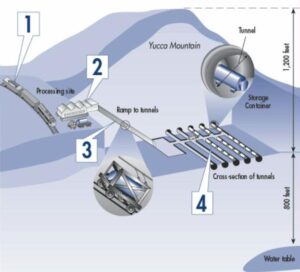

Nuclear waste is a top priority because it emits harmful radiation for hundreds of thousands and even millions of years (SA 2023, Corkhill 2018). Yet despite geological storage being mandated in 1982, there is still nowhere to put it, because Yucca Mountain was closed due to state and federal politics. Yet no place on earth is as safe or as studied. Scientists spent 25 years modeling safety for a million years using hundreds of features, events, and processes (FEPS) in every combination such as climate change, glaciers and icesheets, earthquakes, fractures, faults, volcanism, igneous intrusions, water table rise, erosion, pole reversals, human intrusion, hydrogen or methane gas explosion, effects of corrosion, degradation, radionuclide release, weld failures, mechanical impact, condensation, water intrusion, and chemical interactions on waste packaging, drip shields, seals, rocks, and more (SNL 2008, Alley 2013).

The only country in the world constructing nuclear waste storage is Finland thanks to the culture there, where the public is highly educated, has strong communities, is the most resistant nation to ‘fake news’ and a high trust in institutions (El-Showk 2022, Fitzgerald 2023). The U.S. is practically the opposite, it is hard to imagine an acceptable site ever being found.

How on earth can Congress even consider building advanced nuclear power plants that will generate 2 to 30 times more waste than today’s light water reactors (on an energy basis of megawatt for megawatt) until there is permanent geological storage to put existing and future waste?

Nuclear waste needs to be buried while energy is still cheap and abundant and before climate change floods and sea level rise swamp nuclear power plants. It will take 15 years to reopen Yucca mountain as a repository, and 40 years to find an alternative storage site, plus several more decades to ship spent fuel there. As many nuclear reactors begin closing after 2040, spent fuel may be stranded in place (GAO 2012).

As far as the greatest existential threat of all, nuclear war, Senator Markey of Massachusetts is all alone in creating bills to restrict the first use of nuclear weapons, block a nuclear launch by artificial intelligence, and reduce nuclear weapons and spending on them (S1754, S1186, S1493, S1499).

If peak oil was in 2018 there is not much time left, since scarcity, depressions, and resource wars are likely. Storing nuclear waste will be at the bottom of the to do list, and the waste will remain at hundreds of sites vulnerable to natural disasters, poisoning thousands of future generations and providing bomb material for tomorrow’s generals and revolutionaries.

Who are already here — our worst enemies are native born and members of right-wing machine-gun toting militias and Proud Boys, Pentecostalists trying to bring Jesus back ASAP so the End Times can begin and the righteous raptured into heaven.

The best permanent nuclear waste site is Yucca Mountain. Although legally allowed to store only 70,000 metric tons of waste (to force other states to share in nuclear waste storage), it has enough space to store 220,000 to 630,000 tons, far more than the 88,000 tons that have accumulated at 77 sites in the U.S. (Maden 2009).

Below are my notes from the 2013 Nuclear Waste Administration Act in Senate Bill S1240. Notable quotes:

David Lochbaum, Union of Concerned Scientists. “Spent fuel pools initially designed to hold slightly over one reactor core now hold up to 9 reactor cores. Unlike the reactor cores, the spent fuel pools are not protected by redundant emergency makeup and cooling systems and or housed within robust containment structures having reinforced concrete walls several feet thick. Thus, large amounts of radioactive material – which under the NWPA should be stored within a federal repository designed to safely and securely isolate it from the environment for at least 10,000 years – instead remains at the reactor sites”.

Senator Feinstein, California: “production of nuclear power has a significant downside: it produces nuclear waste that will take hundreds of thousands of years to decay. And unlike most nuclear nations, the United States has no program to consolidate waste in centralized facilities”.

David Boyd, vice chair of the Minnesota Public Utilities Commission doesn’t believe that a new, permanent repository is likely before 2048, and such a distant date is not acceptable. It’s clear to him that “no one involved today is likely to be around to accept responsibility for non-compliance [with the 2048 goal date]. Obviously, a target date so far in the future eliminates any sense of urgency…moreover, the deadline is so distant that potential hosts for [interim] storage facilities would be justifiably nervous about becoming de facto permanent sites”.

I think it is outrageous Yucca mountain was shut down to get Henry Reid elected to the Senate. Yucca was thoroughly vetted, as Alley explains in “Too hot to touch: the problem of High-level nuclear waste”. After Yucca mountain was rejected, a Blue Ribbon Commission was set up to find a new permanent energy storage site, and they recommended states should volunteer. But as Senator Risch of Idaho notes: We’re waiting for a stampede of people to show up and volunteer to have this storage facility in their State. So far the crowd hasn’t shown up. Indeed I’m not aware of anybody who has volunteered. So where do we go if no one volunteers? S.B. 1240 didn’t pass, nor did a preceding nuclear waste bill S. 3469, so it’s not clear if the latest bill, S. 854, will either. Why not?

- The National Academy of Engineers published a paper by Garric and Di Bella (2014) that speculated the bill didn’t pass because it doesn’t have high legislative priority and the Department of Energy hasn’t done anything to advance nuclear waste policy legislation (Garrick, B.J., Di Bella, C.A.W. 2014. Technical Advances for Geologic Disposal of high activity waste. The Bridge, National Academy of Engineering).

- Many environmental groups, such as the Nuclear information & resource service, are worried about safely transporting high-level waste, and got 42,000 signatures against S.B. 1240.

- Geoffrey H. Fettus of the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) explains in testimony below why the NRDC is opposed to S. 1240.

Alice Friedemann www.energyskeptic.com Author of Life After Fossil Fuels: A Reality Check on Alternative Energy; When Trucks Stop Running: Energy and the Future of Transportation”, Barriers to Making Algal Biofuels, & “Crunch! Whole Grain Artisan Chips and Crackers”. Women in ecology Podcasts: WGBH, Financial Sense, Jore, Planet: Critical, Crazy Town, Collapse Chronicles, Derrick Jensen, Practical Prepping, Kunstler 253 &278, Peak Prosperity, Index of best energyskeptic posts

***

Senate 113–123. July 30, 2013. Nuclear Waste hearing on bill S. 1240, the nuclear waste administration act. U.S. Senate Hearing. 115 pages.

DIANNE FEINSTEIN, U.S. SENATOR FROM CALIFORNIA

The byproducts of nuclear energy represent some of the nation’s most hazardous materials, but for decades we have failed to find a solution for their safe storage and permanent disposal.

Most experts agree that this failure is not a scientific problem or an engineering impossibility; it is a failure of government. The Nuclear Waste Administration Act would finally establish a comprehensive nuclear waste policy, addressing the ever-growing amounts of highly radioactive waste that are being stored in communities across the country, costing taxpayers billions of dollars. This issue is too important for politics as usual, which is why I’m proud to join Senators Wyden, Alexander and Murkowski in introducing the Nuclear Waste Administration Act.

This bill would create an independent entity—the Nuclear Waste Administration—with the sole purpose of managing nuclear waste. It would authorize the siting and construction of three types of waste facilities: (1) a ‘‘pilot’’ waste storage facility for waste from shut down reactors, (2) additional storage facilities for waste from other facilities, and (3) permanent repositories to dispose of nuclear waste. The bill also creates a consent-based siting process for both storage facilities and repositories, based on the successful efforts to build waste facilities in other countries. Fees currently collected from nuclear power ratepayers would fund nuclear waste management. Finally, the new Nuclear Waste Administration will be held accountable for meeting Federal responsibilities.

The United States has 104 operating commercial nuclear power reactors that supply one-fifth of our electricity.

However, production of this nuclear power has a significant downside: it produces nuclear waste that will take hundreds of thousands of years to decay.

And unlike most nuclear nations, the United States has no program to consolidate waste in centralized facilities. Instead, we leave the waste next to operating and shut down reactors sitting in pools of water or in cement and steel dry casks. Today, approximately 70,000 metric tons of nuclear waste is stored at commercial reactor sites. This total grows by 2,000 metric tons each year.

In addition to commercial nuclear waste, we must also address waste generated from creating our nuclear weapons stockpile and powering our Navy. Although the Federal government signed contracts committing to pick up commercial waste beginning in 1998, the Federal government’s waste program has failed to take possession of a single fuel assembly. Our government has not honored its contractual obligations. We have been sued, and we have lost. So today, the Federal taxpayer is paying power plant owners to store the waste at reactor sites all over the nation. The cost of this liability is forecast to reach $20 billion by 2020. As we try to manage our growing national debt, we simply cannot tolerate continued inaction.

In January 2012, the Blue Ribbon Commission on America’s Nuclear Future completed a two-year comprehensive study and published unanimous recommendations for fixing our nation’s broken nuclear waste management program. The Commission found that the only long-term, technically feasible solution for this waste is to dispose of it in a permanent underground repository. Until such a facility is opened—which will take many decades—spent nuclear fuel will continue to be an expensive, dangerous burden. That is why the Commission also recommended that we establish an interim storage facility program to begin consolidating this dangerous waste, in addition to working on a permanent repository. Finally, after studying the experience of all nuclear nations, the Commission found that siting these facilities is most likely to succeed if the host states and communities are welcome and willing partners, not adversaries. The Commission recommended that we adopt a consent based nuclear facility siting process.

One of the most important provisions in this legislation is the pilot program to begin consolidating nuclear waste at safer, more cost-efficient centralized facilities on an interim basis. The legislation will facilitate interim storage of nuclear waste in above-ground canisters called dry casks. These facilities would be located in willing communities, away from population centers, and on thoroughly assessed sites.

Some members of Congress argue that we should ignore the need to interim storage sites and instead push forward with a plan to open Yucca Mountain as a permanent storage site.

But the debate over Yucca Mountain—a controversial waste repository proposed in the Nevada desert, which lacks state approval—is unlikely to be settled any time soon.

I believe the debate over a permanent repository does not need to be settled in order to recognize the need for interim storage. Even if Congress and a future president reverse course and move forward with Yucca Mountain, interim storage facilities would still be an essential component of a badly needed national nuclear waste strategy.

By creating interim storage sites—a top recommendation of the Blue Ribbon Commission—we would begin reducing federal liability while our nation sites and builds a permanent repository. Interim storage facilities could also provide alternative storage locations in emergency situations requiring spent nuclear fuel to be moved quickly from a reactor site.

Permanently disposing of our current inventory of nuclear waste will take several decades. Because of that long timeline, interim storage facilities allow us to achieve significant cost savings for taxpayers and utility ratepayers by shuttering a number of nuclear plants.

One thing is certain: inaction is the most costly and least safe option. Our longstanding stalemate is costly to taxpayers, utility ratepayers and communities that are involuntarily saddled with waste after local nuclear power plants have shut down. And it leaves nuclear waste all over the country, stored in all different ways. It’s long overdue for the government to honor its obligation to safely dispose of the nation’s nuclear waste.

Senator JAMES E. RISCH, IDAHO. With all due respect to my good friend from Nevada, we’re waiting for a stampede of people to show up and volunteer to have this storage facility in their State. So far the crowd hasn’t shown up. Indeed I’m not aware of anybody who has shown up and raised their hand and said this is what we want. So where do we go if indeed no one does step up?

Secretary MONIZ. As we have seen from experience in the last 20 years, it’s not workable without State consent. There are many things that need to be done by the Congress and by the State to make it work. Let’s face it, the default option is a highly distributed storage.

Senator RISCH. That is your default. Secretary Moniz. It’s not my default.

DAVID LOCHBAUM, DIRECTOR, NUCLEAR SAFETY PROJECT, UNION OF CONCERNED SCIENTISTS

Spent fuel pools initially designed to hold slightly over one reactor core now hold up to 9 reactor cores. Unlike the reactor cores, the spent fuel pools are not protected by redundant emergency makeup and cooling systems and or housed within robust containment structures having reinforced concrete walls several feet thick. Thus, large amounts of radioactive material – which under the NWPA should be stored within a federal repository designed to safely and securely isolate it from the environment for at least 10,000 years – instead remains at the reactor sites.

UCS wants to see the status quo ended. We strongly advocate accelerating the transfer from spent fuel pools into dry storage.

Accelerating the transfer from spent fuel pools into dry storage reduces risk. The risk reduction is undeniable. The contaminated land area drops from 9400 square miles to 170 square miles and the number of displaced persons drops from 4.1 million to 81,000 [Note: this refers to the Peach Bottom nuclear power plant in Pennsylvania].

For the record, all of the contaminated area and displaced persons in both cases is due to radioactivity released from spent fuel pools. Not a single person is forced to leave from their home, leave their home, due to radioactivity released from dry storage.

The NRC triaged the relative hazards tackling the highest first and the lowest last. After Fukushima the NRC directed its inspectors to examine reactor core and spent fuel pool cooling systems for vulnerabilities in the event of similar challenge. The NRC did not instruct its inspectors to waste a minute examining the low, dry storage hazard. We urge the Congress to accelerate the transfer from spent fuel pools into dry storage. This does not introduce an additional step in the road to repository since spent fuel must be removed from the pools to dry cask in order to be transported. It merely entails taking this step sooner rather than later.

Americans deserve this protection.

Had the Nuclear Waste Policy Act (NWPA) been implemented as enacted, the federal government would have begun accepting spent fuel in 1998. The nominal 3,000 metric tons per year transfer rate from plant sites to the federal repository exceeded the rate at which spent fuel was being generated. Thus, the amount of spent fuel stored at plant sites around the country would have peaked in 1998 at around 38,000 metric tons and steadily declined thereafter. The delay in opening the federal repository meant that spent fuel continued to accumulate at the plant sites. By year end 2011, over 67,000 metric tons remained at plant sites while 0 ounces resided in a federal repository under the NWPA.

The departure from the NWPA plan forced nuclear plant owners to pay for expanded onsite spent fuel storage capacity (e.g., replacing original low-density storage racks in spent fuel pools with high-density racks and building onsite dry storage facilities to supplement storage in wet pools). Plant owners have sued the federal government for recovery of costs they incurred for storing spent fuel at their sites that should have been in a federal repository under the NWPA. The U.S Government Accountability Office reported that these lawsuits cost American taxpayers $1.6 billion with an estimated $19.1 billion of additional liability through 2020.

UCS wants to see the status quo ended by reducing the inventories of irradiated fuel in spent fuel pools. We strongly advocate accelerating the transfer of irradiated fuel from spent fuel pools to dry storage. In our view, currently available and used dry storage technologies can be used to substantially reduce the inventory of irradiated fuel in spent fuel pools, with a goal of limiting it to the equivalent of one or two reactor cores per pool.

Had the federal government met its obligations under the NWPA, spent fuel pools would not contain up to 9 reactor core’s worth of irradiated fuel. More fuel in the pools means a greater risk to the surrounding public if there is a problem with the pools that releases radioactivity.

Because the federal government failed to meet its obligations under the NWPA, spent fuel pools contain much more irradiated fuel and are essentially loaded guns aimed at neighboring communities.

GEOFFREY H. FETTUS, SENIOR ATTORNEY, NATURAL RESOURCES DEFENSE COUNCIL, INC

On September 12, 2012, NRDC testified before this committee on S. 3469, the template for S. 1240. We commended the preceding bill’s adherence to three principles that, in our view, must be complied with if America is ever to develop an adequate, safe solution for nuclear waste—(1) radioactive waste from the nation’s commercial nuclear power plants and nuclear weapons program must be buried in technically sound deep geologic repositories, the waste permanently isolated from the human and natural environments; (2) governing legislation must contain a strong link between developing waste storage facilities and establishing final deep geologic repositories that ensures no ‘‘temporary’’ storage facility becomes a permanent one; and (3) nuclear waste legislation must embody the fundamental concept that the polluter pays the bill for the contamination that the polluter creates.

NRDC cannot support S. 1240 in its present form because the bill: 1) severs the crucial link between storage and disposal; 2) places highest priority on establishing a Federal interim storage facility at the expense of getting the geologic repository program back on track; 3) fails to ensure that adequate geologic repository standards will be in place before the search for candidate geologic repositories sites commences; 4) fails to provide states with adequate regulatory authority over radiation-related health and safety issues associated with nuclear waste facilities in their respective states; and 5) fails to prohibit the Administrator(or Board) from using funds at his disposal to engage in, or support spent fuel reprocessing (chemical or metallurgical), ostensibly to improve the waste form for permanent disposal of spent fuel.

Regrettably, it appears that the authors of S. 1240 have rejected several key recommendations of the President’s Blue Ribbon Commission for America’s Nuclear Future (BRC). Instead, the bill wrongly prioritizes the narrow aim of getting a government-run interim spent fuel storage facility up and running as soon as possible— a priority with potential financial benefits for business interests.

Of the five objections enumerated above, the first one—severing the link between interim and final nuclear waste storage—is possibly of greatest concern because it means the bill could result in the creation of de facto long-term above-ground repositories. As we’ve stressed since the initiation of the BRC process, law should establish a strong linkage that bars an interim or temporary storage site from becoming a de facto repository. NRDC concurs with the former Chairman of the Energy and Natural Resources Committee who cautioned that interim storage needs to be done ‘‘only as an integral part of the repository program and not as an alternative to, or de facto substitute for, permanent disposal.’’

Unfortunately S. 1240 goes further and effectively eviscerates the link between storage and disposal. This guarantees a repeat of the mistakes we have seen made over the past half century and virtually ensures a moribund repository program. Further, NRDC believes that if S. 1240 becomes law, a future Congress will be forced to deal with this issue once again, with no meaningful disposal solution on the horizon.

After more than 55 years of failure, the history of U.S. nuclear waste policy offers Congress all the lessons it needs and it can ignore them only at its peril. Efforts such as the failed bedded salt repository in Lyons, Kansas (1972) and the 1975 abandonment of the 100-year Retrievable Surface Storage Facility (RSSF) are decades distant, but directly relevant to this Committee’s consideration of S. 1240. Adopting a short-term, politically expedient course for interim storage at the expense of durable solutions is the recipe for failure for both storage and disposal facilities. The failed Yucca Mountain project is merely the latest and largest of these debacles. While the BRC rightly recognized the 1987 amendments to the NWPA were ‘‘highly prescriptive’’ and ‘‘widely viewed as being driven too heavily by political considerations,’’ the BRC failed to take into account (or recount) all that has transpired over the past three decades.

Put bluntly, first the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) and then Congress corrupted the site selection process that resulted in selecting Yucca Mountain as the only option for a deep geologic repository. The original NWPA strategy contemplated DOE first choosing the best out of four or five geologic media, then selecting a best candidate site in each medium. Next, DOE was to narrow the choices to the best three alternatives, finally picking a preferred site for the first of two repositories. A similar process was to be used for a second repository. Such a process, if it had been allowed to play out as intended, would have been consistent with elements of the adaptive, phased, and science-based process the BRC Report later recommended.

But instead, DOE first selected sites it had pre-determined. Then in May, 1986 DOE announced it was abandoning a search for a second repository and narrowed the candidate sites from nine to three, leaving in the mix the Hanford Reservation in Washington (in basalt medium), Deaf Smith County, Texas (in bedded salt medium) and Yucca Mountain in Nevada (in unsaturated volcanic tuff medium). All equity in the site selection process was abandoned in 1987 when Congress, confronted with cost of characterizing three sites and strong opposition to the DOE program, amended the NWPA of 1982 to direct DOE to abandon the two-repository strategy and to develop only the Yucca Mountain site. Not by coincidence, at the time Yucca Mountain was DOE’s preferred site, as well as being the politically expedient choice for Congress. The abandonment of the NWPA site selection process jettisoned any pretense of a science-based approach, led directly to the loss of support from the State of Nevada, diminished Congressional support (except to ensure the proposed Yucca site remained the sole site), and eviscerated public support for the Yucca Mountain project.

By ending all impetus for the disposal program, S. 1240 risks sending the nation down another dead-end road.

DAVID C. BOYD Chairman, National Association of Regulatory Utility Commissioners Committee on Electricity, Vice Chair, Minnesota Public Utilities Commission answers questions:

Question: DOE stated in its response to the BRC report its goal to have a repository constructed and operating by 2048. 35 years is a long time to wait. Is this goal reasonable, and if not, what do you believe is a more logical timeframe?

Answer. Based on the history of the repository program, we are not confident a repository will be operating by 2048. In the April 18, 1983 Federal Register, DOE made this statement, ‘‘the 1998 date (to begin permanent disposal of spent nuclear fuel) is called for in the Act, and we believe it to be a realistic date. Our performance will be judged by meeting that date.’’ Performance to-date is non-existent. The bill’s target date of December 2048 (Section 504(b)(C)) for such a repository to be operational is not acceptable. The date is taken from the DOE Strategy’s proposed repository date. That document provides zero support or rationale for this ‘‘new’’ target date. The only thing that is clear is that no one involved with this issue today is likely to be around to accept responsibility for non-compliance. Obviously, a target date so far in the future effectively eliminates any sense of urgency necessary to compel timely government action. Moreover, the deadline is so distant that potential hosts for consolidated storage facilities would be justifiably nervous about becoming de facto permanent sites. We believe there is no way to come up with a timeframe, logical or not, unless this Administration and future Administrations commit to upholding the law and this Congress as well as future Congresses appropriate the necessary funds that have been and continue to be collected for this purpose.

Question. How many storage facilities and repositories do you believe will be needed to handle this nation’s nuclear waste? Should they be co-located? Should they be geographically spread across the country?

Answer. NARUC, as an organization, has not taken a specific position on either issue. Many argue that even if the license for Yucca Mountain is approved and additional waste storage is authorized there, a new geological repository may be required. Logic suggests that, if collocation is a scientifically safe option, it can only reduce the complexity and cost of both transport and security.

MARVIN S. FERTEL, President and Chief Executive Officer, Nuclear Energy Institute answers questions

Question. Several states have laws prohibiting construction of new nuclear power plants until a solution has been found for nuclear waste. To what extent do you see the uncertainty of US policy on spent fuel storage and disposal to be a barrier to the future use of nuclear power?

Answer. A few states do have moratoria on construction until a disposal pathway is available. While these bans do create a barrier to the construction of new nuclear plants in those specific states, the primary barriers are the economic fundamentals of electricity generation, low economic growth and no growth in electricity demand, which has led to excess generating capacity in most parts of the country, and the low cost of natural gas. Five new reactors are currently under construction in the United States and, in these instances, used fuel management was not a significant consideration in the final decision to authorize the projects. The current lack of a federal program, however, did contribute to the Court’s decision to vacate NRC’s temporary storage rule (waste confidence rule). This has resulted in a temporary halt to licensing of new reactors and completion of licensing renewals. So it is imperative that a sustainable program be established as soon as possible.

Question. S.1240 establishes a category for priority waste that literally gets priority when it comes to access to Federal storage. This includes spent fuel at decommissioned power plants, for example. Are there other categories of spent fuel shipments that should get priority that have not been included? For example, should nuclear power plants that have had particular types of safety problems and have more often received a worse-than-‘‘green’’ rating from the NRC get priority?

Answer. The industry is supportive of initially giving priority to used fuel from shutdown plants without an operating reactor. Moving this used fuel would permit the new management entity to ramp-up operations while achieving immediate results and a reduction in liabilities for the taxpayers and it would permit sites which have only used fuel storage remaining to be fully decommissioned and the land used for other purposes. The order in which used fuel will be picked up from commercial reactors is governed by the principle of ‘‘oldest fuel first’’ as outlined in the contracts between the companies and the Department of Energy. The Department of Energy collects used fuel discharge information and, based on this information, creates a queue for prioritizing shipments. This approach for shipping used fuel from commercial nuclear reactors provides a good legal framework but does not provide a practical and efficient framework for moving used fuel. At the appropriate time, the structure of the queue must be addressed by the commercial entities. The goal at that time should be to establish a priority list for used fuel that minimizes operational burdens on operating reactors while optimizing overall system efficiency and cost.

The industry currently safely and securely manages used fuel at reactor sites and decommissioned sites. Operational issues that are identified by either the industry or the Nuclear Regulatory Commission are appropriately resolved through the existing regulatory framework.

While the industry is committed to continual safety improvement, priority should be given to those areas that will achieve the largest safety benefit. For example, the industry’s resources should be devoted to those safety improvements associated with reactor operations and spent fuel pool monitoring (a lesson learned from the Fukushima accident—see question 5 for additional information) and not arbitrarily reducing the inventory of the pools as a result of a worse- than-‘‘green’’ rating from NRC, which in and of itself may not be very safety significant. The legislation as currently drafted provides for ‘‘emergency’’ shipments. This category, in addition to the defined ‘‘priority’’ shipments, provides the new management entity and the industry with sufficient flexibility to manage used fuel without legislatively establishing additional criteria for prioritizing used fuel shipments.

Question. DOE stated in its response to the BRC report its goal to have a repository constructed and operating by 2048. 35 years is a long time to wait. Is this goal reasonable, and if not, what do you believe is a more logical timeframe?

Answer. The industry reacted with frustration to the target date of 2048 for the opening of a new repository. The industry still supports the completion of the Yucca Mountain licensing process and believes that if successfully licensed and appropriately managed and funded the Yucca Mountain repository could be opened well before 2048.

However, if a second repository program is initiated, the industry believes that the target date for beginning operations should be no more than 25 years after program commencement. Being able to meet or exceed this time period, though, will require a focused effort from beginning to end from a new management entity solely dedicated to the project with unfettered access to the Nuclear Waste Fee payments and the corpus of the Nuclear Waste Fund. Key aspects of this effort must include generic repository (NRC and/or EPA) regulations prior to completion of siting, and a requirement for the NRC to complete the licensing review in three years similar to the review period for the Yucca Mountain license application.

Question. This bill sets up a program for the Federal Government to build new storage facilities for spent fuel. I think it makes sense to move spent fuel if it’s going to be cheaper and safer, for example, at decommissioned nuclear power plants where there’s not going to be ongoing operations. However, at some nuclear power plants, there are going to be continued operations, and maintenance, and security, and environmental monitoring for decades to come. It might NOT be cheaper or safer to move this fuel to a central storage site, especially since it will need to be moved again to the repository. Should the bill include a program to help pay for continued on-site storage at nuclear power plant sites if that would be safer and less expensive? What else could Congress do to encourage movement of spent fuel out of reactor pools, such as allowing the Attorney General to enter into negotiations with the utilities to seek their voluntary agreement to transfer their waste to dry cask storage as part of a settlement agreement in return for providing interim storage off-site?

Answer. Ultimately, the quickest way to reduce the inventory in the pools is to establish a sustainable program that can move used fuel off the sites quicker than it is being generated. The industry is committed to the establishment of such a program and will work with the new management entity to maximize efficiency and minimize program cost.

Question. How many storage facilities and repositories do you believe will be needed to handle this nation’s nuclear waste? Should they be co-located? Should they be geographically spread across the country?

Answer. As an estimate, the U.S. commercial nuclear industry has about 70,000 metric tons of spent fuel stored at reactor sites around the country (not including defense waste). The commercial industry produces another 2,000 metric tons of used fuel each year. The number of storage facilities and repositories needed would depend ultimately on the outcomes of the recommended consent-based siting process and the resolution of the Yucca Mountain licensing process. An effective consent-based siting process will permit the state, affected local community and/or tribe to determine what size facility they are willing to host. So the number of facilities greatly depends on what sites come forward during the consent-based process and how much nuclear waste each site can technically and politically accommodate.

The number of nuclear waste management facilities also depends on the schedule for when such facilities become operational. If the Yucca Mountain repository was operational and the statutory limit of 70,000 metric tons was removed, the U.S. may only need that one disposal site as it is generally agreed, based on technical studies performed by the Department of Energy and the Electric Power Research Institute, that Yucca Mountain can accommodate significantly more used fuel than the statutory limit.

Co-locating a repository and storage facility would have advantages. However, NEI believes that the timelines for determining if a site is suitable to host a repository will be considerably longer than for a storage facility. As a result, NEI questions whether attempting to comply with this preference may create unforeseen challenges to siting a facility. If multiple sites for storage and repository are needed, the industry would support geographically diverse locations to minimize the transportation of nuclear waste over long distances. Multiple locations also provide redundancy that would greatly enhance the reliability of the whole nuclear waste management system.

Sally Jameson, Delegate to the Maryland House of Delegates, Chair, Nuclear Legislative Working Group, National Conference of State Legislatures answers questions

Question. Several states have laws prohibiting construction of new nuclear power plants until a solution has been found for nuclear waste. To what extent do you see the uncertainty of US policy on spent fuel storage and disposal to be a barrier to the future use of nuclear power?

Answer. Even though a few states have rescinded their prohibition in the last several years, not having a solution for the removal of spent nuclear fuel (SNF) certainly gives those who oppose nuclear power plants an argument that creates a certain level of fear in the public.

Not having a solution for Spent Nuclear Fuel has clearly propagated questions about fuel pool safety, over packing of pools two to ten times their design capacity and storing spent fuel in highly populated areas or adjacent to populations.

Question. Historically, citizens, local governments, and tribes have expressed interest in hosting nuclear waste facilities, but state-level opposition prevented any deals from being signed. Our bill tries to address this problem by clearly spelling out a role for the state from the beginning. Are there other measures that we should include to address potential differences between local communities and broader, state-wide interests?

Answer. There are a number of legislative options for ensuring the consultation process can integrate all aspects of state government and assure state legislative input. As state legislators represent local communities, ensuring state legislator participation in the consent process would build a system for addressing any potential differences between local communities and state-wide interests.

DAVID LOCHBAUM, Director, Nuclear Safety Project, Union of Concerned Scientists answers questions

Question. The departure from the 1982 Nuclear Waste Policy Act plan forced nuclear plant operators to pay for expanded onsite spent fuel storage capacity. In order to meet this increased need, nuclear plants simply crowded their existing spent fuel pools, placing radioactive materials very close to one another, increasing the risk of a meltdown. Dry cask storage can reduce the crowding of irradiated fuel in spent fuel pools, bringing the pools back to housing a safe level of reactor cores. I am concerned about the safety of workers and the communities adjacent to nuclear plants with crowded fuel pools. Dry cask storage is currently housing only 30% of Wisconsin’s nuclear waste. In order to safeguard communities and plant workers, how can the Department of Energy, or the Nuclear Waste Administration if applicable, incentivize nuclear plant operators to switch to dry storage technology?

Answer. UCS strongly advocates accelerating the transfer of irradiated fuel assemblies from spent fuel pools into dry storage via either the carrot or stick approach. The stick approach could entail measures in the bill that require owners to transfer all irradiated fuel discharged from the reactor more than 10 years ago into dry storage within 20 years of enactment and then to sustain transfers to limit residence time in spent fuel pools to only irradiated fuel discharged from reactors within 10 years. Another stick might be to codify guidelines adopted by the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission after 9/11 to reduce risk of spent fuel pool sabotage. For example, the bill could require that all spent fuel pools be reconfigured to a 1×4 arrangement (one irradiated fuel assembly with three empty storage cells) within 5 years of enactment.

On the carrot side, the bill could pay for dry storage canisters and associated transfers. Another carrot might be for the bill to clearly allow owners of operating reactors to use the decommissioning funds required under 10 CFR 50.75 to pay for onsite dry storage. Or, the bill could provide a carrot in the form of treating any nuclear plant site that has reduced the inventory or irradiated fuel assemblies within its spent fuel pools to less than the equivalent of two reactor cores as having Priority Waste eligible for shipment to a Nuclear Waste Facility. The bill might also feature a combination of carrot(s) and stick(s)—carrot(s) to reward owners who pro-actively undertake accelerated transfers into dry storage and stick(s) to protect the public from further undue lagging.

Question. Our bill establishes a category for priority waste that literally gets priority when it comes to access to Federal storage. This includes spent fuel at decommissioned power plants, for example. Are there other categories of spent fuel shipments that should get priority that have not been included? For example, should nuclear power plants that have had particular types of safety problems and have more often received a worse-than-‘‘green’’ rating from the NRC get priority?

Answer. During the July 30 hearing, Chairman Wyden spoke of spent fuel storage measures that can reduce costs while improving safety. Those reasonable principles may identify spent fuel shipments having secondary priority. For example, dry storage methods are long lasting but not immortal. The U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) issued Information Notice 2012-20 (http:// pbadupws.nrc.gov/docs/ML1231/ML12319A440.pdf) last fall about potential chloride-induced stress corrosion cracking of dry cask storage system canisters. Last year the NRC also issued Information Notice 2012-13 (http:// pbadupws.nrc.gov/docs/ML1216/ML121660156.pdf) about aging degradation of safety materials in spent fuel pools. Owners of operating reactors could pay for the measures necessary to protect safety margins from such degradation mechanisms. There is also the potential for an existing onsite dry storage facility to become filled, requiring its owner to pay for supplemental onsite storage capacity (e.g, construct additional horizontal concrete vaults or pour larger concrete pads for vertical casks). In such cases, shipment from operating reactor sites to a Federal storage site might reduce overall system costs while also increasing safety levels or preserving safety margins. The bill should empower the entity tasked with managing the Federal storage program to authorize spent fuel shipments from operating reactor sites as a secondary priority based on safety management and cost savings grounds.

Question. How many storage facilities and repositories do you believe will be needed to handle this nation’s nuclear waste? Should they be co-located? Should they be geographically spread across the country?

Answer. Science and the consent-based selection process provided for in the legislation should answer these questions rather than the legislation itself. As Senator Alexander suggested during the July 30 committee hearing, a site might require conditions on its acceptance of a storage facility or repository. Those conditions might cap the amount of material received at the site or require that it not be used for both interim storage and ultimate disposal of nuclear waste. The Nuclear Waste Administration would also be a party in the site selection process and would presumably not authorize selection of a site that would result in the need to find too many other sites. If the legislation were to specify x locations with some here and others there, it could impede the ability of the Nuclear Waste Administration and the consent-based process from finding the best answers to these key questions.

Question. This bill sets up a program for the Federal Government to build new storage facilities for spent fuel. I think it makes sense to move spent fuel if it’s going to be cheaper and safer, for example, at decommissioned nuclear power plants where there’s not going to be ongoing operations. However, at some nuclear power plants, there are going to be continued operations, and maintenance, and security, and environmental monitoring for decades to come. It might NOT be cheaper or safer to move this fuel to a central storage site, especially since it will need to be moved again to the repository. Should the bill include a program to help pay for continued on-site storage at nuclear power plant sites if that would be safer and less expensive?

Answer. Yes, the bill should provide funding for continued onsite storage at operating reactor sites when it reduces risk and saves money. The bill should not fund higher risk and higher cost onsite storage methods. For example, operating reactors with spent fuel pools nearly filled to capacity may be required to shuffle the fuel assemblies within the pools to maintain the desired old fuel/new fuel configuration or be required to implement additional maintenance/monitoring measures to mitigate the neutron absorber degradation problem the NRC described last year in Information Notice 2012-13 (available online at http://pbadupws.nrc.gov/docs/ML1216/ ML121660156.pdf). Because the cheaper and lower risk alternative would be to offload fuel assemblies from overcrowded spent fuel pools into dry storage onsite, the bill should not finance this folly. But the bill would improve safety and lower costs by providing financial incentives for owners to accelerate the transfer from spent fuel pools to dry storage. The bill could do so by paying for the dry storage canisters and the costs of loading them.

RON WYDEN, OREGON, CHAIRMAN. It’s my strong belief that the country needs a way to permanently dispose of nuclear waste from commercial nuclear power plants and Defense programs. Continuing to pass the burden of safely disposing of nuclear waste to future generations is not an option. That’s true whether the waste is at shuttered nuclear power plants or if it’s in tanks alongside the Columbia River in the Pacific Northwest. The Federal Government is contractually obligated to take spent fuel for disposal and this liability, already in the billions of dollars, continues to grow with each passing day. The Federal Government is morally obligated to make sure that wastes from the Nation’s nuclear weapons programs are safely disposed of in a permanent repository.

Whether you happen to be for or against opening Yucca Mountain, Yucca Mountain was not designed to be big enough to handle all of the spent fuel in nuclear waste that will need disposal. Today there are roughly 70,000 metric tons of spent fuel already sitting at nuclear plants around our country. The GAO, the Government Accountability Office, estimates that that amount is going to double just from the current generation of nuclear power plants, to over 140,000 metric tons.

Seventy thousand metric tons is the statutory capacity limit for Yucca Mountain until there is a second repository. That leaves no room for the commercial spent fuel that will be generated this year or next year or the year after that. It also leaves no room for the spent fuel from the Navy or for the tens of thousands of canisters of high level waste expected from Hanford and the other Department of Energy nuclear weapons sites.

Continuing to keep spent fuel and high level waste where they are today—in reactor pools that were not originally designed to store large quantities of spent fuel for long periods of time at DOE nuclear sites and at decommissioned nuclear power plants— is an exercise in institutional inertia. I was reminded of a harsh truth when I visited Fukushima. Accidents don’t always follow safety precautions. If plant safety can be improved by reducing the amount of spent fuel stored in existing pools, then there’s an option that ought to be on the table.

It is also is time to come to terms with the fact that having permanent disposal capacity for all of the waste that the country is going to have is not going to be up and running any time soon.

No one who has commented on the subject believes that the U.S. Department of Energy should continue to be in charge of this program. S. 1240 would create a new agency with a 5 member independent oversight board to site and manage the government’s nuclear waste, storage and disposal facilities. There is also a general consensus that the Federal Government needs to work with State and tribal governments in siting these facilities, not in conflict with them.

Finally the bill would also authorize the Secretary of Energy to revisit the decision made after the 1982 act was passed to commingle commercial spent fuel and high level waste in the same disposal system. S. 1240 would require the new agency to begin right away to site new facilities for storage of priority waste. Priority waste includes spent fuel at decommissioned nuclear plants and emergency shipments of spent fuel that present a hazard where they’re stored.

However, storage is not permanent. It’s temporary. The new agency is required to also site a permanent repository. Financial commitment to move ahead with the repository and selection of potential sites for that repository are prerequisites for any additional spent fuel storage facilities to come online.

It has now been 3 decades since Congress passed the Nuclear Waste Policy Act of 1982. In many ways the country is no closer to having a permanent solution to these problems than it was then. If anything, there is even less confidence in the government’s ability to solve these problems and meet its commitments to utilities and their ratepayers. Our goal with this legislation is to get the permanent repository program back on track and to make sure spent fuel and nuclear waste are handled safely until it is.

LISA MURKOWSKI, U.S. SENATOR FROM ALASKA. I’d like to mention an area that I think we’re going to need to address more comprehensibly during this committee process and that’s the transportation of waste in dry cask storage to a storage facility or repository.

According to the NEI, more than 3,000 shipments of used nuclear fuel have been made over the past 40 years by rail, by truck and sometimes barge. While there are a handful of transport containers that are certified by the NRC, there are nearly 1700 dry cask units at operating reactors and stranded and shut down sites representing over 19,000 metric tons of used nuclear fuel. However, no transport containers have been procured for those units in large part because they just don’t have any place to go.

But even if we were to pass this legislation tomorrow significant work needs to be done at the stranded sites. The priority sites that are identified in the bill just to get the storage casks to a rail head. DOE’s Office of Fuel Cycle Technology estimates that it will likely take 12 to 15 years to remove the waste from the stranded sites with the first 5 to 6 years needed to acquire the resources and to prepare the infrastructure.

ERNEST MONIZ, SECRETARY, DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY. I appear before the committee today to reinforce that the Administration is ready and willing to engage with both chambers of Congress to move forward. I believe that S. 1240 provides a workable framework for that engagement. Any workable solution for the final disposition of used fuel and nuclear waste must be based not only on sound science, but also on achieving public acceptance at the local, State and tribal levels. When this Administration took office, the timeline for opening Yucca Mountain had already been pushed back by two decades, stalled by public protest and legal opposition and with no end in sight. It was clear the stalemate could continue indefinitely. Rather than continuing to spend billions of dollars more on a project that faces such strong opposition, the Administration believes a pathway similar to that the Blue Ribbon Commission laid out, a consent based solution for the long term management of our used fuel and nuclear waste, is one that meets the country’s national and energy security needs, has the potential to gain the necessary public acceptance and can scale to accommodate the increased needs of the future that includes expanded nuclear power deployment.

DOE is also working to analyze the characteristics of various geologic media that are potentially appropriate for disposal of radioactive waste. This research will help provide a sound technical basis for a repository in various geologic media, and will help provide confidence in whatever future decisions are made. To leverage expertise and minimize costs, DOE is taking advantage of existing analyses conducted by other countries that have studied similar issues. With regard to borehole disposal, DOE is developing a draft plan and roadmap for a deep borehole project. The project would evaluate the safety, capacity, and feasibility of the deep borehole disposal concept for the long-term isolation of nuclear waste. It would serve as a proof of principle, but would not involve the disposal of actual waste. The project would evaluate the feasibility of characterizing and engineering deep boreholes, evaluate processes and operations for safe waste emplacement and evaluate geologic controls over waste stability.

Secretary MONIZ. The point of the review, ultimately, is to make sure we are doing the best for the taxpayer in disposing of plutonium.

Senator MARIA CANTWELL, WASHINGTON. To me, it’s unacceptable to our State, my constituents, to think that Hanford is just going to end up being that repository for that vast amount of high level Defense waste.

Sally Young Jameson, Maryland Delegate, National Conference of State Legislatures. With regard to the potential siting of a repository or interim storage facility, NCSL recognizes the need to develop processes that are efficient and effective in order to enable a constructive environment for these efforts. However, efforts to streamline this process do not necessitate overlooking the role of State legislatures in the process. In order to ensure that such a decision accurately reflects appropriate levels of State consensus, State legislatures and not just the State’s Governor, must be consulted regularly.

I would just like to say that as a legislator with a nuclear power plant, Calvert Cliffs, is in my region. I just want you to know how important it is that we have a national repository. We have over 72 modules of nuclear waste already stored onsite. There’s 60 more to be added. We want to see that waste removed from our community. Our constituents really would like to see the U.S. Government fulfill its promise to its people.

The Calvert Cliffs Nuclear Power Plant, located on the Western Shore of the Chesapeake Bay, sits just a few miles outside of Maryland’s 28th District, my home district. Calvert Cliffs generally accounts for about one-third of the state’s energy generation, and produces enough power to light up every home and business in Baltimore according to the Maryland Power Plant Research Program. However, due to the lack of a national fuel repository or interim storage site, the plant’s used fuel is forced to remain on site. The plant’s independent spent fuel storage installation (ISFSI) currently contains 72 modules with a total of 1,920 fuel assemblies in dry fuel storage and 1,432 fuel assemblies currently in storage in the Spent Fuel Pool. Additionally, 24 more modules will be added later this year and another 36 are anticipated to be added in the future. The issue of developing a solution to the safe and secure storage of high-level radioactive waste and used nuclear fuel is one of great importance to both myself and my constituents.

RON WYDEN, OREGON, CHAIRMAN. I think you know that the sponsors of the legislation made the judgment right at the outset that we have to have a permanent disposal process for nuclear waste. At the same time, and this was reaffirmed both at Hanford and at Fukushima, our sense was that there’s going to be a lot of spent fuel and nuclear waste that is going to continue to sit in temporary storage for decades to come before it goes to a permanent repository and that is the case wherever the repository is located. The current storage pools and the tanks simply weren’t designed for long-term storage.

Senator MURKOWSKI. If we can get this resolved how do you see new development of new nuclear plants moving forward? Most particularly, the small modular reactors which many of us are very interested in trying to advance.

Secretary MONIZ. I think quite clearly, we need to solve the back end to have any form of nuclear power going forward. Small modular reactors will need storage and geologic repository just as our current reactors do. They may have different fuel forms depending upon their design. But we will certainly need this back end resolved, for sure.

References

Barnard M (2019) Fukushima’s Final Costs Will Approach A Trillion Dollars Just For Nuclear Disaster. CleanTechnica.

Cochran TB et al (2010) Fast Breeder Reactor Programs: History and Status. Research Report 8. Princeton, NJ: International Panel on Fissile Materials. http://libweb.iaea.org/library/eBooks/ fast-breeder-reactor.pdf

Corkhill C et al (2018) Nuclear Waste Management. IOP Publishing Ltd.

El-Showk S (2022) Final Resting Place. Science. https://www.science.org/doi/pdf/10.1126/science.ada1392

GAO (2012) Spent Nuclear Fuel. Accumulating Quantities at Commercial Reactors Present Storage and Other Challenges. United States Government Accountability Office GAO-12-797

GAO (2013) Managing critical isotopes. Stewardship of Lithium-7 is needed to ensure a stable supply. U.S. Government Accountability Office.

Gardner T (2021) Advanced nuclear reactors no safer than conventional nuclear plants, says science group. Reuters.

Greenpeace (2014) Lifetime extension of ageing nuclear power plants: Entering a new era of risk. Greenpeace Switzerland.

Hirsch H (2005) Nuclear Reactor Hazards Ongoing Dangers of Operating Nuclear Technology in the 21st Century. Greenpeace International.

IPFM (2018) International Panel on Fissile Materials, “Fissile Material Stocks” http://fissilematerials.org/

Jaczko G (2019) Confessions of a Rogue Nuclear Regulator. Simon & Schuster.

Jägermeyr J et al (2020) A regional nuclear conflict would compromise global food security. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Jenkens LM et al (2020) Unmanaged climate risks to spent fuel from U.S. nuclear power plants: The case of sea-level rise. Energy Policy.

Johnson J (2013) Radioactive waste safety. Chemical & Engineering news. https://cen.acs.org/articles/91/i44/Radioactive-Waste-Safety.html

Kahn JP (2013) How beer gave us civilization. New York Times

Kottke J (2019) The Lifespans of Ancient Civilizations. Kottke.org

Krall LM et al (2022) Nuclear waste from small modular reactors. PNAS. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2111833119

Lyman (2021) “Advanced” isn’t always better. Assessing the safety, security, and environmental impacts of non-light-water nuclear reactors. Union of concerned scientists.

Maden C (2009)“No Limits for Yucca Mountain?” Nuclear Engineering International. https://www.neimagazine.com/features/featureno-limits-for-yucca-mountain-721/

Mcfarlane A, Ewing RC (2023) Nuclear Waste Is Piling Up. Does the U.S. Have a Plan? We need a permanent national nuclear waste disposal site now, before the spent nuclear fuel stored in 35 states becomes unsafe. Scientific American

Mulder EJ (2021) Overview of X-Energy’s 200 MWth Xe-100 Reactor. Presentation to the NAS Committee January 13.

NAS (2022) Merits and Viability of Different Nuclear Fuel Cycles and Technology Options and the Waste Aspects of Advanced Nuclear Reactors. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26500

Nedopil C (2023) Countries of the Belt and Road Initiative. Shanghai, Green Finance & Development Center, FISF Fudan University, www.greenfdc.org

Olalde M et al (2022) The Cold War Legacy Lurking in U.S. Groundwater. ProPublica

Ramana MV (2021) Small modular & advanced nuclear reactors: A reality check. IEEE Access.

Robock A (2011) Nuclear winter is a real and present danger. Nature 473: 275-6

SA (2016) Stop Wasting Time–Create a Long-Term Solution for Nuclear Waste. Scientific American

SA (2023) Nuclear Waste Is Piling Up. Does the U.S. Have a Plan? We need a permanent national nuclear waste disposal site now, before the spent nuclear fuel stored in 35 states becomes unsafe. Scientific American.

Senate 114 (2016-2-24) Energy & water development appropriations for fiscal year 2017. Senate hearing.

Senate 116 (2019-1-16) The future of nuclear power: Advanced reactors. Senate hearing.

Senate 116-295 (2019-4-30) Pathways to reestablish U.S. global leadership in nuclear energy and S.903, the nuclear energy leadership act. Senate hearing.

Senate 117-120 (2021-3-25) the latest developments in the nuclear energy sector with a focus on ways to maintain & expand the use of nuclear energy in the U.S. and abroad. Senate hearing.

SNL (2008) Features, Events, and Processes for the Total System Performance Assessment. Sandia National Laboratory. 2,048 pages.

St Clair J (2008) Pools of fire. CounterPunch. Project censored: https://web.archive.org/web/20100725030831/http://www.projectcensored.org/top-stories/articles/4-nuclear-waste-pools-in-north-carolina/

Stone R (2016) Spent fuel fire on U.S. soil could dwarf impact of Fukushima. Science Magazine

Thompson G (1999) Risks & Alternative options associated with spent fuel storage at the Shearon Harris nuclear power plant. NC Warn

Toon OB (2019a) Rapidly expanding nuclear arsenals in Pakistan and India portend regional and global catastrophe. Science.

Toon OB et al (2019b) Rapidly expanding nuclear arsenals in Pakistan and India portend regional and global catastrophe. Science Advances.

UCS (2012) Safer storage of spent nuclear fuel. Union of Concerned Scientists.

U.S. House (2015) Testimony of Dr. Peter Vincent Pry at the U.S. House of Representatives Serial No. 114-42. The EMP Threat: the state of preparedness against the threat of an electromagnetic pulse (EMP) event. U.S. House of Representatives.

Von Hippel F et al (2017) Nuclear safety regulation in the post-Fukushima era. Science

Zogopoulis E (2020) Helium: fuelling the future? Energy Industry Review.

Xia L et al (2022) Global food insecurity and famine from reduced crop, marine fishery and livestock production due to climate disruption from nuclear war soot injection. Nature food. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-022-00573-0

Additional reading and notes

The American Geosciences Organization has a review of this session at:

http://www.americangeosciences.org/policy/nuclear-waste-administration-act-2013

The latest nuclear waste bill, S. 854, is sponsored by Senator Lamar Alexander [R-TN]: S.854 – Nuclear Waste Administration Act of 2015, 114th Congress (2015-2016).

The most likely so-called temporary interim sites are likely to be Native American lands (i.e. Skull Valley Goshutes Intian Reservation in Utah), The U.S. DOE sites in South Carolina (Savannah River Site or Waste isolation pilot plant in New Mexico, and Idaho National Lab).