Preface. There are three articles below on this topic. Plus these articles in the news:

Nakagawa T et al (2021) The spatio-temporal structure of the Lateglacial to early Holocene transition reconstructed from the pollen record of Lake Suigetsu and its precise correlation with other key global archives: Implications for palaeoclimatology and archaeology. Global and Planetary Change

The team’s data show that the transition from the ice age to the post-glacial age was characterized by alternations between stable and unstable periods. The domestication of plants didn’t start when the warm climate was established in ca. 13,000 BC, but had to wait until the climate stopped oscillating in short intervals and large amplitudes in ca. 12,000 BC. Agriculture is a subsistence practice that requires planning. But to plan in advance, a stable future is important. When the climate was unstable, agriculture was too risky a practice because accurately predicting the weather in the future wasn’t possible, thus making it difficult to select appropriate crops for agriculture. In such climatic conditions, hunting-and-gathering was a more reasonable subsistence strategy than agriculture because the natural ecosystem consists of diverse species from which humans could expect “something” edible, as opposed to the farmlands. These new findings challenge the traditional view that agriculture was a revolutionary step forward for the history of humanity. Instead, agriculture and hunting-and-gathering were equally reasonable adaptation strategies, depending on whether the climate was stable or unstable. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2021/07/210729095215.htm

2022 Dwindling Mississippi Grounds Barges, Threatens Shipments. Bloomberg. A logjam of more than 100 ships, tugboats and their convoys of barges in the shrinking Mississippi River is threatening to grind trade of grains, fertilizer, metals and petroleum to a halt. Drought has reduced water levels along the biggest US waterway by so much that vessels are running aground. The largest US barge operator, Ingram Barge Co, declared force majeure due to “near-historic” low water conditions on the Mississippi, the top route to get US grains and soybeans to the world market. Some 60% of all grain exported from the US is shipped on the Mississippi River. The logjam is coming at the worst time as the soybean and corn harvests are each about one-fifth complete and supplies will start piling up, and the river is also vital to transport fertilizer.

2021 Atmospheric drying will lead to lower crop yields, shorter trees across the globe

Alice Friedemann www.energyskeptic.com Author of Life After Fossil Fuels: A Reality Check on Alternative Energy; When Trucks Stop Running: Energy and the Future of Transportation”, Barriers to Making Algal Biofuels, & “Crunch! Whole Grain Artisan Chips and Crackers”. Women in ecology Podcasts: WGBH, Jore, Planet: Critical, Crazy Town, Collapse Chronicles, Derrick Jensen, Practical Prepping, Kunstler 253 &278, Peak Prosperity, Index of best energyskeptic posts

***

Berdugo, M., et al. 2020. Global ecosystem thresholds driven by aridity. Science.

Earth’s dryland ecosystem covers 45% of the world’s surface and is home to around a third of its population who depend on these areas for their food and water.

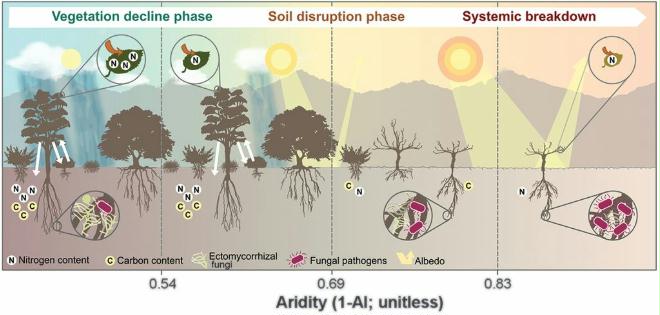

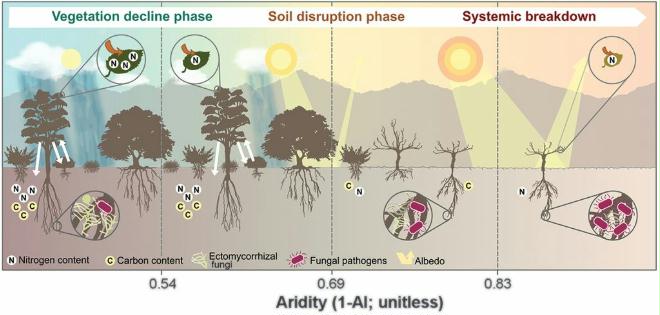

This study found that as aridity increases, dryland ecosystems undergo a series of abrupt changes. This results first in drastic reductions in the capacity of plants to fix carbon from the atmosphere, then substantial declines of soil fertility, drought-tolerant plants replace food crops, and finally vegetation disappears under the most arid and extreme conditions and turns into a desert.

As aridification grows worse, the land becomes more vulnerable to erosion, soil biota maintaining the ecosystem decline, pathogens increase, crops fail.

More than 20% of land may cross these thresholds by 2100 due to climate change.

Hatfield, J., et. al. 2014: Ch. 6: Agriculture. Climate Change Impacts in the United States. The Third National Climate Assessment. 150-174.

- Climate disruptions to agricultural production have increased in the past 40 years and are projected to increase over the next 25 years. By 2050 and beyond, these impacts will be increasingly negative on most crops and livestock.

- Many agricultural regions will experience declines in crop and livestock production from increased stress due to weeds, diseases, insect pests, and other climate change induced stresses.

- Current loss and degradation of critical agricultural soil and water assets due to increasing extremes in precipitation will continue to challenge both rain-fed and irrigated agriculture

- The rising incidence of weather extremes will have increasingly negative impacts on crop and livestock productivity because critical thresholds are already being exceeded.

- Agriculture has been able to adapt to recent changes in climate; however, increased innovation will be needed to ensure the rate of adaptation of agriculture and the associated socioeconomic system can keep pace with climate change over the next 25 years.

- Climate change effects on agriculture will have consequences for food security, both in the U.S. and globally, through changes in crop yields and food prices and effects on food processing, storage, transportation, and retailing. Adaptation measures can help delay and reduce some of these impacts.

The United States produces nearly $330 billion per year in agricultural commodities, with livestock accounting for half of that value. Production of all commodities will be vulnerable to direct impacts (from changes in crop and livestock development and yield due to changing climate conditions and extreme weather events) and indirect impacts (through increasing pressures from pests and pathogens that will benefit from a changing climate). Crop production projections often fail to consider the indirect impacts from weeds, insects, and diseases that accompany changes in both average trends and extreme events, which can increase losses significantly.

Rising average temperatures will increase crop water demand, increasing the rate of water use by the crop. Higher temperatures are projected to increase both evaporative losses from land and water surfaces and transpiration losses (through plant leaves) from non-crop land cover, potentially reducing annual runoff and streamflow for a given amount of precipitation.

By mid-century, when temperature increases are projected to be between 1.8°F and 5.4°F and precipitation extremes are further intensified, yields of major U.S. crops and farm profits are expected to decline. There have already been detectable impacts on production due to increasing temperatures.

One critical period in which temperatures are a major factor is the pollination stage; pollen release is related to development of fruit, grain, or fiber. Exposure to high temperatures during this period can greatly reduce crop yields and increase the risk of total crop failure. Plants exposed to high nighttime temperatures during the grain, fiber, or fruit production period experience lower productivity and reduced quality. These effects have already begun to occur; high nighttime temperatures affected corn yields in 2010 and 2012 across the Corn Belt. With the number of nights with hot temperatures projected to increase as much as 30%, yield reductions will become more prevalent.

Plants have specific temperature tolerances, and can only be grown in areas where their temperature thresholds are not exceeded. As temperatures increase over this century, crop production areas may shift to follow the temperature range for optimal growth and yield of grain or fruit. Temperature effects on crop production are only one component; production over years in a given location is more affected by available soil water during the growing season than by temperature, and increased variation in seasonal precipitation, coupled with shifting patterns of precipitation within the season, will create more variation in soil water availability.

Increasing temperatures cause cultivated plants to grow and mature more quickly. Crops, such as cereals, would grow more quickly, meaning less time for the grain itself to mature, reducing productivity. But because the soil may not be able to supply nutrients at required rates for faster growing plants, plants may be smaller, reducing grain, forage, fruit, or fiber production.

In vegetables, exposure to temperatures in the range of 1.8°F to 7.2°F above optimal moderately reduces yield, and exposure to temperatures more than 9°F to 12.6°F above optimal often leads to severe if not total production losses.

Temperature and precipitation changes will include an increase in both the number of consecutive dry days (days with less than 0.01 inches of precipitation) and the number of hot nights. The western and southern parts of the nation show the greatest projected increases in consecutive dry days, while the number of hot nights is projected to increase throughout the U.S. These increases in consecutive dry days and hot nights will have negative impacts on crop and animal production. High nighttime temperatures during the grain-filling period (the period between the fertilization of the ovule and the production of a mature seed in a plant) increase the rate of grain-filling and decrease the length of the grain-filling period, resulting in reduced grain yields. Exposure to multiple hot nights increases the degree of stress imposed on animals resulting in reduced rates of meat, milk, and egg production.

Climate change poses a major challenge to U.S. agriculture because of the critical dependence of the agricultural system on climate and because of the complex role agriculture plays in rural and national social and economic systems (Figure 6.2). Climate change has the potential to both positively and negatively affect the location, timing, and productivity of crop, livestock, and fishery systems at local, national, and global scales. It will also alter the stability of food supplies and create new food security challenges for the United States

Over time, climate change is expected to increase the annual variation in crop and livestock production because of its effects on weather patterns and because of increases in some types of extreme weather events.

Each crop species has a temperature range for growth, along with an optimum temperature.9 Plants have specific temperature tolerances, and can only be grown in areas where their temperature thresholds are not exceeded. As temperatures increase over this century, crop production areas may shift to follow the temperature range for optimal growth and yield of grain or fruit. Temperature effects on crop production are only one component; production over years in a given location is more affected by available soil water during the growing season than by temperature, and increased variation in seasonal precipitation, coupled with shifting patterns of precipitation within the season, will create more variation in soil water availability. The use of a model to evaluate the effect of changing temperatures

Key Message: Extreme Precipitation and Soil Erosion

Current loss and degradation of critical agricultural soil and water assets due to increasing extremes in precipitation will continue to challenge both rainfed and irrigated agriculture unless innovative conservation methods are implemented. Wind erosion could also increase in areas with persistent drought because of the reduction in vegetative cover.

Several processes act to degrade soils, including erosion, compaction, acidification, salinization, toxification, and net loss of organic matter. Several of these processes, particularly erosion, will be directly affected by climate change. Rainfall’s erosive power is expected to increase as a result of increases in rainfall amount in northern portions of the United States, accompanied by further increases in precipitation intensity. Projected increases in rainfall intensity that include more extreme events will increase soil erosion in the absence of conservation practices. Precipitation and temperature affect the potential amount of water available, but the actual amount of available water also depends on soil type, soil water holding capacity, and the rate at which water filters through the soil.

Iowa is the nation’s top corn and soybean producing state. These crops are planted in the spring. Heavy rain can delay planting and create problems in obtaining a good stand of plants, both of which can reduce crop productivity. In Iowa soils with even modest slopes, rainfall of more than 1.25 inches in a single day leads to runoff that causes soil erosion and loss of nutrients and, under some circumstances, can lead to flooding. Figure 6.9 shows the number of days per year during which more than 1.25 inches of rain fell is increasing.

A few of the ecosystem services provided by soils include:

- the provision of food

- wood

- fiber (i.e. cotton)

- raw materials

- flood mitigation

- recycling of wastes

- biological control of pest

- regulation of carbon and other heat-trapping gases

- physical support for roads and buildings

- cultural and aesthetic values

Productive soils are characterized by levels of nutrients necessary for the production of healthy plants, moderately high levels of organic matter, a soil structure with good binding of the primary soil particles, moderate pH levels, thickness sufficient to store adequate water for plants, a healthy microbial community, and the absence of elements or compounds in concentrations that are toxic for plant, animal, and microbial life.

Erosion is managed through maintenance of cover on the soil surface to reduce the effect of rainfall intensity. Studies have shown that a reduction in projected crop biomass (and hence the amount of crop residue that remains on the surface over the winter) will increase soil loss.

Key Message: Weeds, Diseases, and Pests

Many agricultural regions will experience declines in crop and livestock production from increased stress due to weeds, diseases, insect pests, and other climate change induced stresses.

The growth of atmospheric CO2 concentrations has a disproportionately positive impact on several weed species. This effect will contribute to increased risk of crop loss due to weed pressure.

Weeds, insects, and diseases already have large negative impacts on agricultural production, and climate change has the potential to increase these impacts. Current estimates of losses in global crop production show that weeds cause the largest losses (34%), followed by insects (18%), and diseases (16%). Further increases in temperature and changes in precipitation patterns will induce new conditions that will affect insect populations, incidence of pathogens, and the geographic distribution of insects and diseases. Increasing CO2 boosts weed growth, adding to the potential for increased competition between crops and weeds. Several weed species benefit more than crops from higher temperatures and CO2 levels.

One concern involves the northward spread of invasive weeds like privet and kudzu, which are already present in the southern states. Changing climate and changing trade patterns are likely to increase both the risks posed by, and the sources of, invasive species. Controlling weeds costs the U.S. more than $11 billion a year, with most of that spent on herbicides. Both herbicide use and costs are expected to increase as temperatures and CO2 levels rise. Also, the most widely used herbicide in the United States, glyphosate, loses its efficacy on weeds grown at CO2 levels projected to occur in the coming decades. Higher concentrations of the chemical and more frequent sprayings thus will be needed, increasing economic and environmental costs associated with chemical use.

Insects are directly affected by temperature and synchronize their development and reproduction with warm periods and are dormant during cold periods. Higher winter temperatures increase insect populations due to overwinter survival and, coupled with higher summer temperatures, increase reproductive rates and allow for multiple generations each year. An example of this has been observed in the European corn borer (Ostrinia nubialis) which produces one generation in the northern Corn Belt and two or more generations in the southern Corn Belt. Changes in the number of reproductive generations coupled with the shift in ranges of insects will alter insect pressure in a given region.

Key Message: Heat and Drought Damage

The rising incidence of weather extremes will have increasingly negative impacts on crop and livestock productivity because critical thresholds are already being exceeded.

Climate change projections suggest an increase in extreme heat, severe drought, and heavy precipitation. Extreme climate conditions, such as dry spells, sustained droughts, and heat waves all have large effects on crops and livestock. The timing of extreme events will be critical because they may occur at sensitive stages in the life cycles of agricultural crops or reproductive stages for animals, diseases, and insects. Extreme events at vulnerable times could result in major impacts on growth or productivity, such as hot-temperature extreme weather events on corn during pollination. By the end of this century, the occurrence of very hot nights and the duration of periods lacking agriculturally significant rainfall are projected to increase. Recent studies suggest that increased average temperatures and drier conditions will amplify future drought severity and temperature extremes. Crops and livestock will be at increased risk of exposure to extreme heat events. Projected increases in the occurrence of extreme heat events will expose production systems to conditions exceeding maximum thresholds for given species more frequently.

California’s Wine, Fruit, & Nut production will begin declining as soon as 2050

In fact, it’s already happening. In 2000, the number of chilling hours in some regions was 30% lower than in 1950. A warmer climate will affect growing conditions, and the lack of cold temperatures may threaten perennial crop production (Figure 6.6), which have a winter chilling requirement (expressed as hours when temperatures are between 32°F and 50°F) ranging from 200 to 2,000 cumulative hours. Yields decline if the chilling requirement is not completely satisfied, because flower emergence and viability is low. Projections show that chilling requirements for fruit and nut trees in California will not be met by the middle to the end of this century.

Impacts on Animal Production

Animal agriculture is a major component of the U.S. agriculture system. Changing climatic conditions affect animal agriculture in four primary ways: 1) feed-grain production, availability, and price; 2) pastures and forage crop production and quality; 3) animal health, growth, and reproduction; and 4) disease and pest distributions. The optimal environmental conditions for livestock production include temperatures and other conditions for which animals do not need to significantly alter behavior or physiological functions to maintain relatively constant core body temperature.

Optimum animal core body temperature is often maintained within a 4°F to 5°F range, while deviations from this range can cause animals to become stressed. This can disrupt performance, production, and fertility, limiting the animals’ ability to produce meat, milk, or eggs. In many species, deviations in core body temperature in excess of 4°F to 5°F cause significant reductions in productive performance, while deviations of 9°F to 12.6°F often result in death. For cattle that breed during spring and summer, exposure to high temperatures reduces conception rates. Livestock and dairy production are more affected by the number of days of extreme heat than by increases in average temperature. Elevated humidity exacerbates the impact of high temperatures on animal health and performance.

Animals respond to extreme temperature events (hot or cold) by altering their metabolic rates and behavior. Increases in extreme temperature events may become more likely for animals, placing them under conditions where their efficiency in meat, milk, or egg production is affected. Projected increases in extreme heat events will further increase the stress on animals, leading to the potential for greater impacts on production. Meat animals are managed for a high rate of weight gain (high metabolic rate), which increases their potential risk when exposed to high temperature conditions. Exposure to heat stress disrupts metabolic functions in animals and alters their internal temperature when exposure occurs. Exposure to high temperature events can be costly to producers, as was the case in 2011, when heat-related production losses exceeded $1 billion.

Livestock production faces additional climate change related impacts that can affect disease prevalence and range. Regional warming and changes in rainfall distribution have the potential to change the distributions of diseases that are sensitive to temperature and moisture, such as anthrax, blackleg, and hemorrhagic septicemia, and lead to increased incidence of ketosis, mastitis, and lameness in dairy cows.

Goats, sheep, beef cattle, and dairy cattle are the livestock species most widely managed in extensive outdoor facilities. Within physiological limits, animals can adapt to and cope with gradual thermal changes, though shifts in thermoregulation may result in a loss of productivity. Lack of prior conditioning to rapidly changing or adverse weather events, however, often results in catastrophic deaths in domestic livestock and losses of productivity in surviving animals.

Key Message: Rate of Adaptation

Agriculture has been able to adapt to recent changes in climate; however, increased innovation will be needed to ensure the rate of adaptation of agriculture and the associated socioeconomic system can keep pace with climate change over the next 25 years.

In the longer term existing adaptive technologies will likely not be sufficient to buffer the impacts of climate change without significant impacts to domestic producers, consumers, or both. Limits to public investment and constraints on private investment could slow the speed of adaptation. Adaptation may also be limited by the availability of inputs (such as land or water), changing prices of other inputs with climate change (such as energy and fertilizer), and by the environmental implications of intensifying or expanding agricultural production.

In addition to regional constraints on the availability of critical basic resources such as land and water, there are potential constraints related to farm financing and credit availability in the U.S. and elsewhere. Research suggests that such constraints may be significant, especially for small family farms with little available capital.

Farm resilience to climate change is also a function of financial capacity to withstand increasing variability in production and returns, including catastrophic loss. As climate change intensifies, “climate risk” from more frequent and intense weather events will add to the existing risks commonly managed by producers, such as those related to production, marketing, finances, regulation, and personal health and safety factors. The role of innovative management techniques and government policies as well as research and insurance programs will have a substantial impact on the degree to which the agricultural sector increases climate resilience in the longer term.

Key Message: Food Security

Climate change effects on agriculture will have consequences for food security, both in the U.S. and globally, through changes in crop yields and food prices and effects on food processing, storage, transportation, and retailing.

Food security includes four components: availability, stability, access, and utilization of food. Following this definition, in 2011, 14.9% of U.S. households did not have secure food supplies at some point during the year, with 5.7% of U.S. households experiencing very low food security.

In addition to altering agricultural yields, projected rising temperatures, changing weather patterns, and increases in frequency of extreme weather events will affect distribution of food- and water-borne diseases as well as food trade and distribution. This means that U.S. food security depends not only on how climate change affects crop yields at the local and national level, but also on how climate change and changes in extreme events affect food processing, storage, transportation, and retailing, through the disruption of transportation as well as the ability of consumers to purchase food. And because about one-fifth of all food consumed in the U.S. is imported, our food supply and security can be significantly affected by climate variations and changes in other parts of the world. The import share has increased over the last two decades, and the U.S. now imports 13% of grains, 20% of vegetables (much higher in winter months), almost 40% of fruit, 85% of fish and shellfish, and almost all tropical products such as coffee, tea, and bananas. Climate extremes in regions that supply these products to the U.S. can cause sharp reductions in production and increases in prices.

In an increasingly globalized food system with volatile food prices, climate events abroad may affect food security in the U.S. while climate events in the U.S. may affect food security globally. The globalized food system can buffer the local impacts of weather events on food security, but can also increase the global vulnerability of food security by transmitting price shocks globally.

Senate 113-245. February 14, 2013. Drought, fire and freeze: the economics of disasters for America’s agricultural producers. U.S. Senate hearing.

Excerpts from this 195-page document follow.

DEBBIE STABENOW, MICHIGAN. Nobody feels the effect of weather disasters more than our nation’s farmers and ranchers, as we all know, whose livelihoods depend on getting the right amount of rain, the right amount of sunshine, getting it all together the right way at the right time. All too frequently, an entire season’s crop can be lost, as we know. Or an entire herd must be sent to slaughter due to the lack of feed.

The year 2012 was a year of unprecedented destruction, from drought, freezes, wildfires, hurricanes, and tornadoes, including the tornadoes that hit Mississippi and other parts of the South last weekend, and my heart goes out to all the survivors of those devastating storms. Our country experienced two of the most destructive hurricanes on record last year, Isaac and Sandy. We experienced the warmest year on record ever in the contiguous United States, which, coupled with the historic drought, produced conditions that rivaled the Dust Bowl. Wildfires raged in the West. In the Upper Midwest and Northeast, warm weather in February and March caused trees to bloom early, resulting in total fruit destruction when temperatures dropped down to the 20s again in April, and we certainly were hit hard with that in Michigan. California and Arizona experienced a freeze just last month, threatening citrus, strawberries, lettuce, and avocados. We learned last week that our cattle herd inventories are the lowest in over six decades, which has had broad-ranging impacts, including job losses in rural communities as processing facilities and feedlots idle.

The drought has left many of our waterways with dangerously low water levels. Lake Michigan, Lake Huron have hit their all- time lowest water levels. Barge traffic on the Mississippi, our most vital waterway has nearly ground to a halt. We have seen major disruptions and increased transportation costs for commodities and fertilizers. Today, we will hear from officials at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, NOAA, and the Department of Agriculture about the disasters we faced last year. We also will hear directly from those affected by these disasters. Thanks to our successful Crop Insurance Program, many farmers will be able to recover their losses. For those farmers who did not have access to crop insurance or the other risk management tools we worked so hard to include in our Senate-passed farm bill, the future is less certain. Unfortunately, instead of a farm bill that gave those farmers certainty, we ended up with a partial extension that creates the haves and haven’ts. Low crop producers that participate in crop insurance not only get assistance from crop insurance, which is essential, but some will continue to receive direct payments, as well, regardless if they have a loss. Meanwhile, many livestock producers and specialty crop growers who suffered substantial losses will not receive any assistance.

We all know that farming is the riskiest business in the world and altogether employs 16 million Americans.

ROGER PULWARTY, Director, National Integrated Drought Information System, NATIONAL OCEANIC & ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION, BOULDER, COLORADO

Drought is a pallet of the American experience, from the Southwest in the 13th century to the events of the 1930s and the 1950s to the present. From 2000 to 2010, the annual average land area affected by drought in the United States was 25 percent. Prior to the 2000s, this number stood at 15 percent. 2012 ended as one of the driest years on record, having had five months in which over 60 percent of the country was in moderate to extreme drought. It was also the warmest year on record. Only 1934 had more months with over 60 percent of the U.S. in moderate to severe drought. 1934 was also a warm year.

Drought conditions continue across much of the nation. According to one estimate, the cost of the 2012 drought is in excess of $35 billion, based on agriculture alone.

However, it is important to note the drought-related impacts cross a broad spectrum, from energy, tourism, and recreation in the State of Colorado where I live, to wildfire impacts. According to the National Interagency Fire Center in Boise, over nine million acres were burned last year, which had only happened twice before in the record, 2006 and 2007, since 1960. Low river levels also threaten commerce on the vital Mississippi shipping lanes, affecting transportation of agricultural products. As many of you know, half of the transport on the Mississippi is agriculturally based.

An important feature of conditions in 2012 was the persistence of the area of dryness and warm temperatures, the magnitude of the extremes, and the large area they encompassed.

Twenty-twelve began with about 32 percent of the U.S. in moderate to exceptional drought. The drought reintensified in May, and you can see a jump in the figure there. And by the end of August, the drought had expanded to cover 60 percent of the country, from the Central Rockies to the Ohio Valley and the Mexican to the Canadian borders. Several States had record dry seasons, including Arkansas, Kansas, Nebraska and South Dakota.

The drought years of 1955 and 1956 have the closest geographical pattern to what we have seen to date, and the year 1998, now the second-warmest year on record, and 2006, the third-warmest year on record, have the closest temperature pattern to what we see.

So as of this morning, we have released the U.S. Drought Monitor that gives you present conditions, which people have in front of them. And what we are pointing out in this case is the drought continues across many parts of the Midwest and the West. The physical drivers of drought are linked to sea surface temperatures in the Tropical Pacific and Atlantic Oceans.

As you can see from the last figure on the U.S. Drought Monitor, a dry pattern is expected over the upcoming three months across the South and the Midwest. Prospects are limited for improvement in drought conditions in California, Nevada, and Western Arizona. Drought development and persistence is forecasted for Texas by the end of April. The drought and warm temperatures in the Midwest are firmly entrenched into February, placing a greater need for above-normal spring rains if the region is to recover. This area is now becoming the epicenter of the 2013 drought. Despite some relief, much of the Appalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint River Basin remain under extreme drought conditions, including low ground water levels, and Georgia is now in its driest two-year period on record.

JOE GLAUBER, CHIEF ECONOMIST, U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE, WASHINGTON, DC

Row crop producers have generally fared well, despite the adverse weather, in large part due to higher prices and protection from the Federal Crop Insurance Program, which has helped offset many of the yield losses. For uninsured producers, or producers of crops for which insurance is unavailable, however, crop losses have had a more adverse effect. Livestock producers experienced high feed costs and poor pasture conditions this year with limited programs to fall back on, particularly since key livestock disaster programs authorized under the 2008 farm bill are currently unfunded.

What had started out as a promising year for U.S. crop production, with favorable planting conditions supporting high planted acreage and expectations of record or near- record production turned into one of the most unfavorable growing seasons in decades. Crop production estimates for several major crops declined throughout the summer. By January 2013, final production estimates for corn were down almost 28 percent from our May projections. Sorghum was down 26 percent, while soybeans fell about six percent over the same period.

As a result, prices for grains and oil seeds soared to record highs in the summer. Higher prices and crop insurance indemnity payments helped offset crop losses for many rural crop producers. Roughly 85 percent of corn, wheat, and soybean area, almost 80 percent of rice area, and over 90 percent of cotton area is typically enrolled in the Crop Insurance Program, and for those of you who were around back in 1988, this contrasts sharply with what the experience was in 1988 when we had this massive drought in the Midwest. At that time, only about 25 percent of the area, insurable area, was enrolled in the program. So, again, very, very strong participation has helped offset those losses.

As of February 11, just this Monday, about $14.2 billion in indemnity payments have been made to producers of 2012 crops suffering crop or revenue losses. We think that these indemnity payments will likely go higher. They could be as high as 16 or 17 billion dollars before we are done.

On the other hand, looking at the livestock, dairy, and poultry producers, they are facing very high feed costs for most—they faced very high feed costs for most of 2012, and the high prices are likely to persist through much of 2013 until new crops become available in the fall. And in addition to these high feed costs, cattle producers have been particularly hard hit by poor pasture conditions and a poor hay crop. Almost two- thirds of the nation’s pasture and hay crops were in drought conditions, with almost 60 percent of pasture conditions rated poor or very poor for most of July, August, and September 2012. December 1 stocks for hay were at their lowest level since 1957.

The U.S. cattle and calf herd, as was mentioned in your statement, is at its lowest level since 1952. Dryness in the Southern Plains has persisted for over two years and resulted in large liquidation in cattle numbers. The January 1 NASS Cattle Report indicated that total cattle and calf numbers in Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas alone declined by 3.4 million head between 2011 and 2013. The reduction is a 13.6 percent decline and almost equals the net decline in the U.S. herd over the same period. Likewise, dairy producers have faced high feed costs and poor pasture conditions, and higher temperatures during the summer also adversely affected milk production.

Net cash income is forecast lower in 2013 for all livestock, dairy, and poultry sector. Feed costs make up 51 percent of expenses for dairy, about 20 percent for beef cattle, 42 percent for hogs, and 35 percent for poultry farm businesses.

Major concerns related to persistent drought conditions remain. Fifty-nine percent of wheat area, the winter wheat area, 69 percent of cattle production, and 59 percent of hay acreage remains under drought conditions. Forty-three percent of the winter wheat production is located in areas under extreme or exceptional drought conditions, down only slightly from the 51 percent in August.

Chairwoman STABENOW. How long before we are going to have crop insurance available for specialty crop growers?

Mr. GLAUBER. I think we have made some improvements there. As you know, I sit on the Federal Crop Insurance Board. We have seen several products, new products that have come in that have extended crop insurance to some specialty crops. We have made some changes, for example, in the cherry policy with a revenue product. I think the overall liability for specialty crops right now is around 10 to 13 billion dollars. Certainly, we would like to see that improved. The difficulty is that with a lot of these crops, they are very small with not a lot of producers, and sometimes some of the producers are not interested in crop insurance. Now, what we have seen over the last five years, ten years, which is very different than, I would say, 15 years ago, is the fact that a lot of producers now are interested in developing these products.

Our major issue, as you know, in the Midwest and the Southwest, in particular, the Colorado Basin, is that we are having back- to-back dry years, and a third year of that puts our systems completely under stress. The forecast for this season is that, in fact, we are projecting drier conditions.

Senator KLOBUCHAR. Mississippi River transportation is my next question. In 2012, as you know, the barge traffic on the Mississippi was greatly impacted by the drought. It was more difficult to transport grain abroad and more farm inputs up-river to our farmers in Minnesota. We were very scared at the end of the year they were actually going to have to stop barge traffic. Could you talk about that a little and how this could impact our ability to stay competitive, as so many agriculture products go down the Mississippi?

Mr. GLAUBER. Yes. We, too, were very concerned with it because it looked like, particularly late December, early January, that there would be a halt in traffic. Now, understand, the upper part of the Mississippi, as you well know, you stop shipping because of the winter weather. But I think there were a couple of good things. One, the best thing, is that we got rain. The Corps was able to go in and clear out some of the disruptions in the river and then we got adequate rain and barge traffic is moving very well. I will say this. Because of the lower corn harvest and lower soybean harvest and the fact that so much more grain is going to China, it was probably less stress than it might have been under, say, 15 years ago. But, still, the best news is that we have adequate water.

Senator KLOBUCHAR. It is good, but it was a close call and I think it is something that we have to prepare better for next time and have a plan in place. Drought-resistant seeds—what efforts is the USDA taking to speed the adoption of such drought-hardy varieties developed using biotech or conventional breeding?

Mr. GLAUBER. Most of the breeding for seed breeding is in private hands these days. They do it better. There are a lot of profits to be made in that industry and they are working very hard. My understanding is, is that we should be seeing some disaster-resistant, purely disaster-resistant strains come on the market just in the next few years. We know upstream, as well, about 20 percent of what comes into the basin is coal and 20 percent is about fertilizers, as well.

Senator ROBERTS. We have got two years of sustained drought and another one coming, according to our renowned forecaster here. But Kansas producers, once again, put seeds in the ground. Many will once again fire up their tractor and their planter in another six weeks. They manage their risk and protect their operations from Mother Nature’s destruction through the purchase of crop insurance.

Unfortunately, livestock producers do not have a similar safety net. However, with the support of Secretary Vilsack last year, the Department authorized the emergency haying and grazing of Conservation Reserve Program acres in all Kansas counties, including the emergency grazing on CP-25 for the first time. You do not do that unless you have a very, very serious problem.

According to USDA reports last year, over 9,000 emergency haying and grazing contracts allowed haying and grazing on over 470,000 acres in Kansas, that’s a lot of acres. But as we continue to experience what we have experienced in the 1950s and back in the 1930s, what considerations has the Department given to allowing emergency haying and grazing of CRP acres for 2013??

Mr. GLAUBER. A lot of these producers have been hanging on with very, very tight or negative margins. And again, I cited these numbers. Over three million, three-and-a-half million head down from just two years ago in your region of the country. And so it is very critical. I think any help that we can get to the producers to help them make it through to better prices, we will be working with your office on that.

Senator ROBERTS. As you know, many ranchers simply culled their herds and lost their genetics and many are out of business. Northwest Kansas producers irrigating from the Ogallala Aquifer, they must work to conserve their water, but current RMA practices do not have a middle ground between fully irrigated and dry land practices and we need a mechanism to allow limited irrigation to be fairly rated.

Senator BENNET. —we have now had two years in a row, and it sounds like we are going to have a third year of drought in our region. And I wonder if you could talk about the specific challenges that NOAA projects for producers in the water-scarce Western region of our country.

Mr. PULWARTY. I hope I am wrong, as well. The State of Colorado, as you know, in the Front Range, where I live and others do, we get 30 to 40 percent of our water from the Colorado Basin itself. The Colorado Basin came in at 44 percent in the previous water year. So far, the fall snow pack has not been as significant as we would like it. In some places, it is 40, some places 60%, and we hope that picks up in March and April.

However, right now, based on what is happening in the Pacific Ocean and the Atlantic Oceans, we are not projecting an improved set of conditions in those basins, the Upper Basin, including the San Juan and places like that.

The area in terms of the basin is experiencing some lower precipitation and snow pack, and it is also experiencing a combination of high temperatures, however driven. Something else that is happening in that basin has to do with some of our rural communities, where there is rain-fed agriculture.

the combination of temperature and drought is actually creating the die-off of key vegetation that holds our soils together. And the result, then, is dust storms, dust on snow, which lets the runoff and melt occur even earlier than we are accustomed to managing it.

From that standpoint, and looking into the future, while we are seeing some improvement in the lower Colorado Basin—Arizona, Southern California, Nevada—we are expecting that to be short- lived into April. From the standpoint of the Upper Basin, and again, I hope I am, in fact, wrong, we are not projecting significant new inputs of snow unless we get heavy rainfall events later in the spring.

One of the reasons why that is the case is when it has been dry for a year before, even when you get significant snow pack, a lot of that disappears because the soil just picks it up. In 2005, we had 100 percent of snow pack, but the runoff was 70 percent of what we expected because the springtime had been warm.

The Colorado is now in its second longest ten-year period of low flows on record. If we average over the last ten years, the flow has been at average or less, and this is in an already over-allocated system, as you know better than I do.

The issue concerning the basin, where 30 million people live and where we have seven States reliant on the water, is very much at the edge. The demand exceeded supply about ten years ago, so it does not take a major drought to put us into areas of contention.

And to be perfectly honest, given the uncertainty, certainly, there are issues in introducing drought-resistant crops. There are issues in introducing risk pooling and insurance. But where the Conservation Reserve Programs come in is the admission that we are uncertain about the future, that it leaves us the flexibility to manage for the pieces that we are uncertain about. And I think that is the richest contribution from the standpoint of an understand what the weather incline is doing, naturally or otherwise, and then what the buffers in our system supply.

Senator COWAN. We also need to be thinking about new threats that our farmers and fishermen are facing. The climate change and more frequent and intense extreme weather events threaten our agricultural economy, and I am pleased that the committee is discussing this important issue today.

According to the Climate Vulnerability Initiative, the U.S. is among the top ten countries that will be most adversely affected by desertification and sea level risk, and this does not bode well for either our farmers or fishermen.

Senator BAUCUS. It is a real honor for me to introduce Leon LaSalle. Leon is a Native American rancher. The real deal, several generations. His grandfather, Frank Billy, is one of the first to found the ranch on the Chippewa Cree Reservation of Montana. It actually is part of the Rocky Boys Reservation. We have got seven reservations in Montana. Leon and his family are real stalwarts, and one of the reservations is Rocky Boys and the Chippewa Cree are the Tribal members in that reservation. They raise Black Angus around the Bears Paw Mountains between Rocky Boys, up around Havre, Montana. It is sort of a real standout, that is, as a landmark in our State. We are very proud of it. Leon was featured in a book. The book was called Big Sky Boots. It is the working seasons of a Montana cowboy. He has a great quote in that book. He said he thinks there is a growing disconnect between the general public and agriculture producers. Well, Leon, I have got to tell you, the same thing is true in Washington, D.C. There is a disconnect between the people here and the people who represent the rest of the country, and maybe you can kind of help connect those dots a little bit here when it comes time for you to testify. We are really very honored to have you here because you are a great credit to the Tribe and to the State of Montana and your industry. Leon is also on the Board of Directors of the Montana Stockgrowers and one of the guiding lights there,

LEON LASALLE, RANCHER, HAVRE, MONTANA

We have installed numerous conservation practices specifically designed to preserve and protect our natural resources. Even though we have implemented these conservation measures, there are times when my family’s ranch has been struck so hard by weather- related disasters that we have sought economic assistance. The Federal Livestock Disaster Programs have been that assistance.

The Native American Livestock Feed Program is a great example of a program that helped when feed was short. In drought years, when there is little or no hay to feed our livestock, ranchers like me must purchase hay at a premium. Sometimes by the time the hay reaches the ranch, the freight is more than the cost of the hay itself.

These programs provide the only financial relief available when a rancher was faced with loss of livestock or forage to feed them. There is no insurance for catastrophic livestock losses, such as those experienced by Southeastern Montana ranchers during the horrific wildfires of 2012.

I have helped neighbors prepare applications for LIP, and on one sad occasion, I participated as a third-party witness when several cattle fell through the ice and drowned while trying to shelter themselves from a stinging Montana blizzard.

Mother Nature throws a variety of natural events in the path of a Montana rancher. Our weather is uncertain, sometimes severe. We find our markets are even vulnerable to the effects of drought, as well. Drought has reduced the number of cattle available, and processing facilities have closed as a result, thus affecting our price. If weather and markets are not the issue, then many of my fellow ranchers are challenged by the ever- increasing predator losses.

ANNGIE STEINBARGER, FARMER, EDINBURGH, INDIANA

we now farm 1,500 acres of corn and soybeans as well as a small cow-calf operation in the State. We find our association with various farm organizations, such as the Indiana Soybean Alliance, invaluable to the success of our operation. The Indiana Soybean Alliance is an arm of the American Soybean Association, a trade organization that represents our nation’s 600,000 soybean farmers on national and international policy issues.

It has always been our dream to farm. My husband and I both knew that the only way to make our dreams a reality were to save our pennies and work off-farm incomes in hope that, one day, my father would give us the opportunity to participate in the farming operation. Mike worked in the seed, tile ditching, and bulk milk transport business while I worked in fertilizer, chemical, and crop insurance businesses.

We started farming 600 acres and have increased the operation to 1,500 acres. Roughly one-half of our acres are on a share arrangement with our landlords. We continue to work off- farm, as it is still not self-supporting. Mike sold the milk truck to buy a school bus and I continue to work in the crop insurance and do the farm recordkeeping.

To manage our thin, light soil types, we started our farming operation employing conservation tillage techniques, using such programs as CRP and NRCS cost share funding. To this day, we are still advocates of no-till farming as a way to preserve our soil and maintain soil moisture. As a result of our conservation efforts, our average yields are 150 bushels of corn and 50 bushels of soybeans.

Our best corn was on the farm with the pivot. Under the pivot, it was 200 bushels to the acre. And outside of the pivot, ten. Needless to say, there was not anything to put in the grain bins. Due to the drought and heat, the grain quality was very poor and we even shipped our grain that was going to be fed for livestock.

The number one barrier to increasing our yields is the lack of water. Dry weather in the months of July and August always limit our yield potential. We find crop insurance an effective tool in managing risk when we experience these weather events. We began using crop insurance in 1991 as a way to maintain our cash flow and prevent us from having to borrow money. I actually have lost money over buying crop insurance over the last 20- year time span. It was not until the last two drought years that it actually paid for us to have crop insurance.

JEFF SEND, CHERRY FARMER, LEELANAU, MICHIGAN

I grew up working my grandfather’s 40 acres. Now, my wife and I, Anita, farm 800 acres of sweet and tart cherries. Putting some of the land into the Federal Farm and Ranch Land Protection Program is one of the tools we use to expand our operation. Our youngest daughter and her husband work with us and they someday hope to take over the farm. I also have managed a receiving station for 37 years. I have a working relationship with 35 growers who bring me cherries to be weighed, inspected, shipped to ten different processors in Michigan, Wisconsin, and the State of New York that I work with. I currently am serving as Vice Chair of the Cherry Marketing Institute Board. CMI is a national organization for tart cherry farmers. I am also a Vice Chair of the National Cherry Growers and Industries Foundation, which is a sweet cherry organization. Year in and year out, Michigan produces 75 percent of the United States tart cherries. However, that was not the case in 2012. Last year was the most disastrous year I and the cherry industry have ever experienced. Our winter was much warmer than normal, with little snow and ice on the Great Lakes. In mid-March, there were seven days of 80-degrees temperatures, which is unheard of in Northern Michigan. Cherry trees began to come out of dormancy and began to grow. This left them completely vulnerable to the next 13 freezes in April. This extreme weather in Michigan was one of the worst disasters we had ever seen. Sweet cherries endured freezes slightly better than tart cherries. But to top things off, we were hit with a worst case bacterial canker I had ever seen. There is no treatment for this disease, which affects the fruit buds.

In Michigan, we have the capacity to grow 275 million pounds of tart cherries. In 2012, our total was 11.6 million pounds.

There is no tart cherry insurance available at all for our industry, so my fellow growers and I had no risk management tool to get through this very difficult year. NAP insurance is available, but the policy starts at 50% loss and then pays out only 50% of that number. Farmers are left with only about 25% of coverage, and there is a $100,000 cap. This does not come close to covering our expenses. My costs on my farm alone are between three-quarters and a million dollars.

Tree fruits must be maintained whether there is a crop or not on them. You carry on with the same practices in order to keep them healthy. So expenses remain the same. Imagine working for a year-and-a-half with no paycheck and still having the same expenses.

I worry about our young farmers, who haven’t built up any equity. No income with all the same expenses is formula for disaster. There needs to be something to help farmers stay in business when natural disaster hits. A few days that we have no control over can put us out of business.

BEN E. STEFFEN, FARMER, STEFFEN AG, INC., HUMBOLDT, NEBRASKA

My family, our employees, and I produce milk, corn, soybeans, wheat, and hay on our farm at Humboldt in Southeast Nebraska. We milk 135 cows on 1,900 acres of non-irrigated dryland farm, and I have family members at home right now caring for and feeding animals so that I can be here today.

My family, our employees, and I produce milk, corn, soybeans, wheat, and hay on our farm at Humboldt in Southeast Nebraska. We milk 135 cows on 1,900 acres of non-irrigated dryland farm, and I have family members at home right now caring for and feeding animals so that I can be here today. This nation has benefited from a food supply that is plentiful, inexpensive, and of the highest quality, and securing that food supply for the future is clearly a responsible public policy. Facing a growing world population, it is a moral imperative. The impact of fire and drought has hit our farming operation and those of our neighbors. The price of high-quality dairy hay has gone up by 50 percent, and the price of lower- quality hay suitable for beef animals has more than doubled. While we appreciated last year’s release of Conservation Reserve Program acres for emergency haying and grazing, we would like to see efforts made for an earlier release date for those acres. This would dramatically improve the quality and the quantity of those forages.

My neighbors in Western Nebraska have been dealt a particularly hard blow by wildfires, and nearly 400,00 acres, approximately half the State—equivalent to half the State of Rhode Island—were burned in 2012. On those ranches, feed supplies were wiped out, fences were destroyed, and cattle have been liquidated. I would urge you to consider some tax relief to help those ranchers regain their footing. Ladies and gentlemen, our nation’s cattle herd is at a 61-year low and consumers will feel this damage for years.

Livestock contributed $10 billion to Nebraska’s economy in 2011 and crop production contributed $11.7 billion.

Another risk management tool that we employ is diversification. We include both livestock and crops in our business. In order to manage price risk, we constantly watch the changing world markets and the prices for the products we sell, and we accept the challenge of using futures and options contracts. But we, along with thousands of other producers and processors, were victimized by the genius of mismanagement at MF Global when our accounts were frozen in the subsequent bankruptcy. We continue to wait for the return of a slowly rising percentage of our funds.

To further protect our soil and water, we began using cover crops years ago. But participation in the Conservation Security Program gave us a push to go beyond the program requirements, and last year, we planted nearly 60 percent of our acres to cover crops. This practice holds great promise for conserving our soil, saving water, building quality, and sequestering carbon, but we need more research in this area. I urge Congress and this committee to prioritize funding for both basic and applied agricultural research and our Land Grant system of universities created by the Morrill Act of 1862.

Mr. STEFFEN. As I mentioned in my testimony, I would point our again to the no-till techniques we have been using for 40 years on our operation, to save soil, conserve water, and improve our crops. I would also point out that we are making extensive use of cover crops, and those crops planted in conjunction with our traditional crops offer us a way to catch more moisture and snowfall, to improve the way water and rainfall percolates into the soil and it is absorbed so that we are able to capture and store more water in that soil by using those cover crops. It is a way to increase the organic matter levels in the soil, and that makes the soil more productive and increases its ability to hold water.

Senator BAUCUS. Following on Senator Donnelly’s point, it has always struck me how farmers and ranchers have a better perspective on life. They are more philosophical. Why? Because they know they can’t control their fate as much as some people in cities think they can, erroneously. You can’t control the weather. You can’t control price. Cost, you can’t control. You take what you get, but you have got to manage it as well as you possibly can. It is very, very difficult and it is kind of humbling. It gives you a sense of life and the importance of hard work and doing one’s best. Whereas on the other hand, I think a lot of people in the city get a little arrogant and they think they can control everything, and obviously, they can’t.