Preface. I can’t imagine that there’s a better book on rationing out there, but of course I can’t be sure, I don’t feel the need to find others on this topic after reading this book. As usual, I had to leave quite a bit out of this review, skipping medical care rationing entirely among many other topics. Nor did I capture the myriad ways rationing can go wrong, so if you ever find yourself in a position of trying to implement a rationing system, or advocating for a rationing system, you’ll wish you’d bought this book. I can guarantee you the time is coming when rationing will be needed, in fact, it’s already here with covid-19. I’ve seen food lines over a mile long.

As energy declines, food prices will go up and at some point gasoline, food, electricity, and heating as well, all of them ought to be rationed.

Though this might not happen in the U.S. where the most extreme and brutal capitalism exists. Here the U.S. is the richest nation that ever existed but the distribution of wealth is among the most unfair on the planet. When the need to ration strikes, economists will argue against it I’m sure, saying there’ll be too much cheating and it will be too hard to implement. Capitalism hates price controls. That’s why “publicly raising the question of curbing growth or uttering the dread word “rationing” in the midst of a profit-driven economy has been compared to shouting an obscenity in church”.

Republicans constantly want to cut back the affordable care act and the food stamp program SNAP. Companies keep their workforces as small as possible and shift jobs and factories overseas to nations with lower wages and fewer regulations. They fight hard to restrict the rights of organized labor. All this has resulted in higher productivity, but the rewards go to shareholders and executives, not employees.

So, I wouldn’t count on rationing when times get hard – hell, that’s already apparent with covid-19 aid. The Trump administration & republicans were happy to hand out a $2 trillion dollar tax cut to the already rich, but when it came to covid-19 relief so people wouldn’t be evicted from their homes and afford to buy food with, they gave out money just once and as I write this in mid-October 2020 Republicans won’t compromise with the Democrats to give out any more relief money. Even if Biden is elected, the economy can’t recover until a vaccine is invented and given to everyone. By then the economy may be so broken it will be hard to fix. And since peak oil has already happened, we can’t recover, growth is at an end. Soon “The Long Emergency” Kunstler wrote about it begins.

Let’s hope I’m wrong and that Homeland Security or some other government agency has already got emergency rationing plans in place. I’ve seen the cities of Denver, Chicago, and other city-level plans. They are usually very high level, and cover who should call who, lists of nursing homes to evacuate and the like. But there’s no actual stockpile of food or blankets or rationing plans. When I spoke to someone in California’s emergency planning unit, I was told it this won’t happen because it would be too costly a bureaucracy to set up, and any perceived maldistribution would undo the political fortunes of the party in power.

So, you’d better plan to grow as much of your own food as possible during energy decline, the level of inequality and selfishness in the United States is truly striking. There may be rationing in some localities. Try to find a good community (by reading the posts here), gain skills, and help others out whenever you have a chance to create a bubble of mutual aid and kindness in this cold cruel capitalistic world.

Related

2021 China Panic-Hoards Half Of World’s Grain Supply Amid Threats Of Collapse. Beijing has managed to stockpile more than half of the world’s maize and other grains that have resulted in rapid food inflation and triggered famine in some countries. China has approximately 69% of the globe’s maize reserves in the first half of the crop year 2022, 60% of its rice, and 51% of its wheat. The one thing Beijing cannot have is discontent among its citizens triggered by food shortages and or soaring prices; that’s why central planners spent $98.1 billion importing food in 2020, up 4.6 times from a decade earlier, according to the General Administration of Customs of China. For the first eight months of this year, China imported more food than in 2016. China’s acquisition of the world’s food supply has helped push food prices to decade highs. The U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization estimated the food price index is currently at a ten-year high.

Alice Friedemann www.energyskeptic.com Author of Life After Fossil Fuels: A Reality Check on Alternative Energy; When Trucks Stop Running: Energy and the Future of Transportation”, Barriers to Making Algal Biofuels, & “Crunch! Whole Grain Artisan Chips and Crackers”. Women in ecology Podcasts: WGBH, Planet: Critical, Crazy Town, Collapse Chronicles, Derrick Jensen, Practical Prepping, Kunstler 253 &278, Peak Prosperity, Index of best energyskeptic posts

***

Stan Cox. 2013. Any Way You Slice It: The Past, Present, and Future of Rationing. The New Press.

When energy trading companies, led by Enron Corporation, created shortages in the state’s recently deregulated power industry, they caused wholesale electricity prices to jump by as much as 800%, with economic turmoil and suffering the result. The loss to the state was estimated at more than $40 billion. That same year, Brazil had a nationwide electricity shortfall of 10%, which was proportionally larger than the shortage in California. But the Brazilian government avoided inflation and blackouts simply by capping prices and limiting all customers, residential and commercial, to 10% lower consumption than that of the previous year, with severe penalties for exceeding the limit. No significant suffering resulted. The California crisis is viewed as one of America’s worst energy disasters, but, says Farley, “No one even remembers a ‘crisis’ in Brazil in 2001.

In Zanzibar, for example, resort hotels and guesthouses sited in three coastal villages consume 180 to 850 gallons of water per room per day (with the more luxurious hotels consuming the most), while local households have access to only 25 gallons per day for all purposes.

The mechanisms for non-price rationing are many and varied. The more familiar include rationing by queuing, as at the gas pump in the 1970s; by time, as with day-of-week lawn sprinkling during droughts; by lottery, as with immigration visas and some clinical trials of scarce drugs; by triage, as in battlefield or emergency medicine; by straight quantity, as governments did with gasoline, tires, and shoes during World War II; or by keeping score with a nonmonetary device such as carbon emissions or the points that were assigned to meats and canned goods in wartime.

If we allow the future to be created by veiled corporate planning, the fairly predictable consequence will be resource conflicts between the haves and have-nots—or rather, among the haves, the hads, and the never-hads.

It’s quite possible (indeed very common, I would guess) to be simultaneously concerned about the fate of the Earth and worried that the necessary degree of restraint just isn’t achievable. We’ve been painted into a corner by an economy that has a bottomless supply of paint. Overproduction, the chronic ailment of any mature capitalist economy, creates the need for a culture whose consumption is geared accordingly.

Whenever there’s a ceiling on overall availability of goods, no one is happy. And when a consumer unlucky enough to be caught in such a situation is confronted with explicit rationing—a policy that she experiences as the day-to-day face of that scarcity—it’s no wonder that rationing becomes a dirty word. That has always been true, but an economy that is as deeply dependent on consumer spending as ours would view explicit rationing as a doubly dirty proposition. In America, freedom of consumption has become essential to realizing many of our more fundamental rights—freedom of movement, freedom of association, ability to communicate, satisfactory employment, good health care, even the ability to choose what to eat and drink—and no policy that compromises those rights by limiting access to resources is going to be at all welcome.

No patriotic American can or will ask men to risk their lives to preserve motoring-as-usual. —Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes explaining the U.S. government’s gasoline rationing plan, April 23, 1942

Carter was neither the first nor the last leader to use martial language when urging conservation and sacrifice. According to the environmental scholar Maurie Cohen, “Experience suggests that the use of militaristic representations can be an effective device with which to convey seriousness of purpose, to marshal financial resources, to disable opponents, and to mobilize diverse constituencies behind a common banner. Martial language can also communicate a political message that success may take time and that public sacrifice may be required as part of the struggle.”

As World War I ground on into its third year in the summer of 1917, U.S. exports of wheat and other foods were all that stood between Europe’s battle-weary populations and mass hunger. America’s annual food exports rose from 7 to 19 million tons during the war. As a result, the farms of the time, which were far less productive than those of today, were hard-pressed to satisfy domestic demand. By August 1917, with the United States four months into its involvement in the war, Congress passed the Lever Act, creating the United States Food Administration and the Federal Fuel Administration and giving them broad control of production and prices. Commodity dealers were required to obtain licenses from Food Administrator Herbert Hoover, and he had the power to revoke licenses, shut down or take over firms, and seize commodities for use by the military. In September, the Toledo News-Bee announced that the “entire world may be put on rations soon” with Hoover acting as “food dictator of the world.”8 But as it turned out, Hoover wasn’t much of a dictator. According to the historian Helen Zoe Veit, restrictions consisted mostly of jawboning, as “food administrators simultaneously exalted voluntarism while threatening to impose compulsory rations should these weak, ‘democratic’ means prove insufficient”; however, “many Americans wrote to the Food Administration to say that they believed that compulsion actually inspired cheerful willingness, whereas voluntarism got largely apathetic results.”9 There were in fact a few mandatory restrictions. Hoarding of all kinds of products was prohibited, and violators could be punished with fines or even imprisonment. “Fair-price lists” ran in local newspapers and retailers were expected to adhere to them. But controls on prices of wheat and sugar were not backed up with regulation of demand. That led to scarcities of both commodities, as consumers who could afford to buy excessive quantities often did so.

Meanwhile, the Fuel Administration had to deal with shortages of coal, which at that time was the nation’s most important source of energy for heating, transportation, and manufacturing. Heavy heating demand in the frigid winter of 1917–18 converged with higher-than-normal use of the railway system (largely for troop movements) to precipitate what has been called the nation’s first energy crisis. The administration resorted to a wide range of stratagems to conserve coal, including factory shutdowns, division of the country into “coal zones” with no trade between zones, and a total cutoff of supplies to country clubs and yacht owners. The administration announced that Americans would be allowed to buy only as much coal as was needed to keep their houses at 68 degrees F. in winter.

The need to conserve petroleum led to a campaign to stop the pastime of Sunday driving.

The campaign against Sunday driving was carried out enthusiastically, perhaps overly so, by self-appointed volunteer citizens. Garfield complained that the volunteers had become “tyrranous,” punishing violators in ways that “would have staggered the imagination of Americans twelve months earlier.” Government officials assumed that their

Although food shortages persisted despite the drive for voluntary moderation, rationing remained off the table. Veit explained how the U.S. government’s insistence on voluntarism was an effort to draw a contrast between democratic America and autocratic, “overrationed” Germany. Rationing, the argument went, had undermined German morale while the United States was managing to rescue Europe and feed its own population “precisely because it never forced Americans to sacrifice, but instead inspired them to do so willingly.” (Hoover’s Home Conservation director Ray Wilbur asserted that, before the war, “we were a soft people,” and that voluntary sacrifice had strengthened the nation.) But in World War I America, price controls acting alone did not prevent shortages, unfair distribution, and deprivation. From that experience, the economic historian Hugh Rockoff concluded that “with prices fixed, the government must substitute some form of rationing or other means of reducing demand” because “appeals to voluntary cooperation, even when backed by patriotism, are of limited value in solving this problem.” The reluctance to use rationing was tied to views on democracy. According to Veit, the most powerful men in Washington, including Hoover and President Woodrow Wilson, viewed democracy as “synonymous with individual freedom,” while another view of democracy that was widely held at the time required “equality of burden.” Under the second definition, “rationing was inherently more democratic as it prevented one group (the patriotic) from bearing the double-burden of compensating for another (the shirkers).

In practice, Hoover’s Food Administration valued free-market economics more highly than either personal freedom or fairness. Official language was always of voluntary sacrifice, but there’s more than one way to rope in a “volunteer.” Ad hoc committees in schools, workplaces, churches, and communities kept track of who did and didn’t sign Hoover’s food-conservation pledge or display government posters in their kitchen windows. In urging women to sign and comply with the Hoover pledge, door-to-door canvassers laid on the hard sell, often with the implication of an “or else” if the pledge was refused. Statements from government officials to the effect of “we know who you are” and explicit branding of nonsigners as “traitors” were highly effective recruiting techniques. But millions of poor and often hungry Americans had no excess consumption to give up. A Missouri woman told Hoover canvassers that yes, she would accept a pledge card so that she could “wipe her butt with it,” because she “wasn’t going to feed rich people.” As Veit put it, “the choice to live more ascetically was a luxury, and the notion of righteous food conservation struck those who couldn’t afford it as a cruel joke.”

With pressure building, the U.S. government probably would have resorted to rationing had World War I continued through 1919. The major European combatants, whose ordeal had been longer and tougher, did have civilian rationing, and the practice reappeared across Europe with the return of war in 1939.

When World War II broke out in Europe, the United States once again mounted a campaign to export food and war materials to its allies. Soon after America entered the war, the first items to require rationing were tires and gasoline. Those moves can be explained, in Rockoff’s words, by the “siege motive,” the result of absolute scarcity imposed by an external cutoff of supply. The rubber and tire industries were indeed under siege, with supplies from the Pacific having been suddenly cut off. The processes for making synthetic rubber were known, but there had not been time to build sufficient manufacturing capacity. The government’s first move was to buy time by calling a halt to all tire sales. With military rubber requirements approaching the level of the economy’s entire prewar output, Leon Henderson, head of the Office of Price Administration (OPA), urged Americans to reduce their driving voluntarily to save rubber. But, unwilling to rely solely on drivers’ cooperation, the government got creative and decided to ration gasoline as an indirect means of reducing tire wear. The need for gas rationing had already arisen independently in the eastern states. At the outbreak of the war, the United States was supplying most of its own oil needs. With much of the production located in the south-central states, tankers transported petroleum from ports on the Gulf Coast to the population centers of the East Coast. But in the summer of 1941, oil tankers began to be diverted from domestic to transatlantic trade in support of the war effort, and all shipping routes became highly vulnerable to attack by German submarines. With supplies strictly limited, authorities issued ration coupons that all drivers purchasing gasoline were required to submit, and also banned nonessential driving in many areas.

Police were asked to stop and question motorists if they suspected a violation and “check on motorists found at race tracks, amusement parks, beaches, and other places where their presence is prima facie evidence of a violation.” Drivers also were required to show that they had arranged to carry two or more passengers whenever possible. Energy consumption was further curtailed by restrictions on the manufacture of durable goods, including cars. At one point, passenger-car production was shut down altogether. That, according to Rockoff, was in a sense “the fairest form of rationing. Each consumer got an exactly equal share: nothing.”

LIMITED RATIONING HAD LIMITED SUCCESS

It became clear early on that rationing of food and other goods would become necessary as well. The OPA announced that “sad experience has proven the inadequacy of voluntary rationing. . . . Although none would be happier than we if mere statements of intent and hortatory efforts were sufficient to check overbuying of scarce commodities, we are firmly convinced that voluntary programs will not work.”26 With some exceptions, such as coffee and bananas, the trigger for rationing foodstuffs was not the siege motive. The United States was producing ample harvests and continued to do so throughout the war, but the military buildup of 1942 included a commitment to supply each soldier and sailor in the rapidly expanding armed services with as much as four thousand calories per day. Those hefty war rations, along with exports of large tonnages of grain to Britain and other allies, pulled vast quantities of food out of the domestic economy. Without price controls, inflation would have ripped through America’s food system and the economy, and the price controls could not have held without rationing.

The first year of America’s involvement in the war, there was only loose coordination among agencies responsible for production controls, price controls, and consumer rationing, and as a result the government was unable to either keep prices down or meet demand for necessities. In late 1941 and early 1942, polls showed strong public demand for broader price controls. Across-the-board controls were imposed in April 1942. But over the next year, prices still rose at a 7.6 percent annual rate, so in early 1943 comprehensive rationing of foods and other goods was announced. In April, Roosevelt issued a strict “Hold-the-Line Order” that allowed no further price increases for most goods and services. Only that sweeping proclamation, backed up as it was by a comprehensive rationing system, was able to keep inflation in check and achieve fair distribution of civilian goods. In late 1943, the OPA was getting very low marks in polls—not because of opposition to rationing or price controls, but because people were complaining that they needed even broader and stricter enforcement. It’s important to note that OPA actions were often motivated as much by wariness of political unrest as by a concern for fairness. Amy Bentley, a historian, explains that the experience of the Great Depression was fresh in the minds of government officials, and they felt that, with the war having re-imposed nationwide scarcity, ensuring equitable sharing of basic needs was essential if a new wave of upheaval and labor radicalization was to be avoided. In publicity materials, the OPA stressed the positive, buoyed by comments from citizen surveys, such as the view of one woman that “rationing is good democracy.”

Consumer rationing by quantity took two general forms: (1) straight rationing (also referred to at various times as “specific” or “unit” rationing), which specified quantities of certain goods (tires, gas, shoes, some durable goods) that could be bought during a specified time period at a designated price; and (2) points rationing, in which officials assigned point values to each individual product (say, green beans or T-bone steak) within each class of commodity (canned vegetables or meats). Each household was allocated a certain number of points that could be spent during the specified period. Price ceilings were eventually placed on 80 percent of foodstuffs, and ceilings were adjusted for cost of living city by city. Determining which goods to ration and what constituted a “fair share” required a major data-collection effort. The OPA drew information from a panel of 2,500 women who kept and submitted household food diaries. The general rules and mechanics of wartime rationing, while cumbersome, were at least straightforward. Ration stamps were handled much like currency, except that they had fixed expiration dates. Businesses were required to collect the proper value in stamps with each purchase so that they could pass them up the line to wholesalers and replenish inventories. Many retailers had ration bank accounts from which they could write ration checks when purchasing inventory; that spared them the inconvenience of handling bulky quantities of stamps and avoided the risk of loss or theft. Although stamps expired at the end of the month for consumers, they were valid for exchange by retailers and wholesalers for some time afterward. Therefore, the OPA urged that households destroy all expired ration stamps, warning that pools of excess stamps could “breed black markets.” The link between the physical stamp and the consumer was tightly controlled. Only a member of the family owning a ration book could use the stamps, and stamps had to be torn from the book by the retailer, not the customer. Stamps for butter had to be given to the milkman in person at time of delivery; they were not to be left with a note.

When consumption of some products is restricted by rationing, people spend the saved money on nonrationed products, driving up their prices. Therefore, Britain’s initial, limited program covering bacon and butter did little to protect the wider economy. Families were plagued by inflation, as well as by shortages and unfair distribution of still-uncontrolled goods; demand swelled for “all-around rationing.”32 Restrictions on sugar and meat began early in 1940, in order to keep prices down, ensure fairness, and reduce dependence on imports. Tea, margarine, and cooking fats were included at midyear. As food scarcity took hold, worsening in the winter of 1940–41, Britons demanded that rationing be extended to a wider range of products to remedy growing inequalities in distribution. They got what they asked for.

The quantities allowed per person varied during the course of the rationing period but were never especially generous: typical weekly amounts were four to eight ounces of bacon plus ham, eight to sixteen of sugar, two to four of tea, one to three of cheese, six of butter, four to eight of jam, and one to three of cooking oil. Allowances were made. Pregnant women and children received extra shares of milk and of foods high in vitamins and minerals, while farmworkers and others who did not have access to workplace canteens at lunchtime received extra cheese rations. Quantities were adjusted for vegetarians. In its mechanics, the system differed from America’s in that each household was required to register with one—and only one—neighborhood shop, which would supply the entire core group of rationed foods. As the war continued, it became clear that this exclusive consumer-retailer tie was unpopular, so the government introduced a point-rationing plan in December 1941, permitting consumers to use points at any shop they chose.33 In both the UK and America, most of the day-to-day management of the rationing systems was, necessarily, handled at the local level. Administration of the system was decentralized. According to Bentley, “The 5,500 local OPA boards scattered across the country, run by over 63,000 paid employees and 275,000 volunteers, possessed a significant amount of autonomy, enabling them to base decisions on local considerations. The real strength of the OPA, then, lay less in the federal office than in its local boards.” In large cities from Baltimore to San Francisco, a “block leader plan” was instituted to help families deal with scarcity.

The block leader, always a woman, would be responsible for discussing nutritional information and sometimes rationing procedures and scrap drives with all residents of her city block. The Home Front Pledge (“I will pay no more than the top legal prices—I will accept no rationed goods without giving up ration points”), administered to citizens by the millions, was backed by clear-cut rules and was legally enforceable, so it was taken much more seriously than the Hoover Pledge of 1917–18. In Britain’s system, the Ministry of Food oversaw up to nineteen Divisional Food Offices, and below them more than 1,500 Food Control Committees, each of which included ten to twelve consumers, five local retailers, and one shop worker, that dealt with the public through local Food Offices.

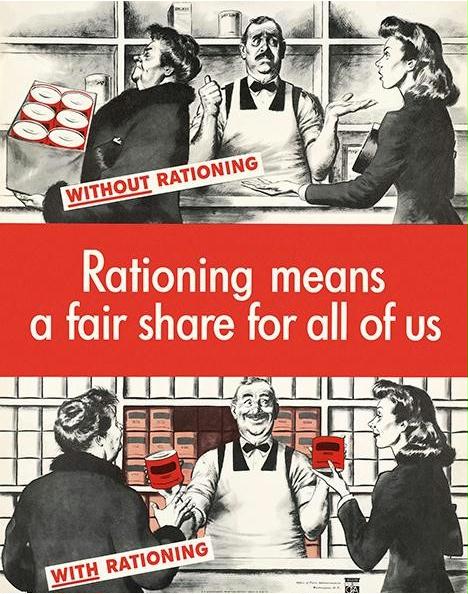

“FAIR SHARES FOR ALL” ARE ESSENTIAL Other Allied nations, as well as Germany and the other Axis powers, also imposed strict rationing. In the countries they occupied, the Nazis enforced extremely harsh forms of rationing among local populations in order to provide more plentiful resources to German troops and civilians. A 1946 report by two Netherlands government officials, poignant in its matter-of-factness, shows in meticulous detail through numerous graphs and descriptions how the calorie consumption and health status of that country’s population suffered and how many lives were lost under such strict rationing. Average adult consumption dropped as low as 1,400 calories per day during 1944. Meager as it was, that was an average; because of restrictions on food distribution, many people, especially in the western part of the country, received much less food and starved. By that stage of the war, according to the authors, “People were forced more and more to leave the towns in search of food in the production areas. Many of them, however, did not live through these food expeditions.

The OPA’s job was made easier, notes Bentley, by the fact that “most Americans understood that their wartime difficulties were minor compared with the hardships in war-torn countries.” Soon after the initiation of food rationing, the Office of War Information estimated that, conservatively, “civilians will have about 3 percent more food than in the pre-war years but about 6 percent less than in 1942. There will be little fancy food; but there will be enough if it is fairly shared and conserved. Food waste will be intolerable.” Total availability of coffee, canned vegetables, meat, cheese, and canned milk was often as high as before the war. Those items were rationed not because they were especially scarce but in order to hold down demand that otherwise would have ballooned under the price controls that were in effect. There was, for instance, an explosion of demand for milk in the early 1940s, when prices were fixed, but the dairy industry blocked attempts to initiate rationing. Consumption shot up, and severe shortages developed in pockets all over the country. Everything but rationing was attempted: relaxing health-quality standards, prohibiting the sale of heavy whipping cream, and reducing butterfat requirements. But the problem of excess demand persisted. Huge quantities of fruits and vegetables were exported in support of the war effort, leaving limited stocks for civilian use. The OPA kicked off 1943 with a plan under which households would be allowed to keep in their own homes no more than five cans of fruits or vegetables per occupant at any one time. A penalty of eight ration points would be assessed for each excess can. There is little evidence that the ban was actually enforced, and neither home-canned goods nor fresh produce was covered by the order.40 Home canners could get a pound of sugar for each four quarts of fruits they planned to can without surrendering ration coupons; however, sugar restrictions sidelined home brewers and amateur wine makers. Commercial distilling for civilian consumption ceased, but the industry reassured customers that it had a three-year supply of liquor stockpiled and ready to sell, so there was no need to ration.

Bread and potatoes were exempted from rationing, to provide a dietary backstop. With caloric requirements thus satisfied by starchy foods, protein became the chief preoccupation. Red meat had already held center stage in the American diet for decades; consumption at the beginning of World War II was more than 140 pounds per person per year, well above today’s average of about 115 pounds. During the war, the government aimed to provide a full pound of red meat per day to each soldier; therefore, according to officials, only 130 pounds per year would remain for each civilian. A voluntary “Share the Meat” program, introduced in 1942, managed to lower average annual consumption by a mere three pounds. When the necessity for stronger curbs became evident, rationing was introduced in 1943, and soon consumption dropped steeply, to 104 pounds per civilian. Farm families were permitted to consume as much as they wanted of any kind of meat they produced on the farm without surrendering ration coupons, but farm owners who did not cultivate their own land were not. Elsewhere, the feeling of scarcity was pervasive. For those who craved more meat, there was little consolation to be found in a chicken leg. At that time, poultry was not highly regarded as a substitute for red meat, so average consumption was only a little over twenty pounds per year—less than one-third of today’s level.42 The OPA tightened price ceilings on poultry but did not ration it.43

By April 1, 1943, even vegetable-protein sources such as dried beans, peas, and lentils had been added to the list of rationed items. To make a half pound of hamburger go further, the American Red Cross Nutrition Service suggested the use of “extenders,” including dried bread and bread crumbs, breakfast cereals, and “new commercial types” of filler. Cooks became accustomed to substituting jelly and preserves for butter; preparing sardine loaf, vegetable loaf, cheese, lard, and luncheon meat; and substituting “combination dishes such as stews, chop suey, chili, and the like for the old standby dishes such as choice roasts and steaks and chops.” Americans sought out protein-and calorie-heavy food wherever they could, partly because, in those days, thinness evoked memories of hard times. The OPA, for example, “served notice on Americans . . . that they will do well, if they want to preserve that well-fed appearance, to stop dreaming of steaks and focus their appetites and point purchasing power on hamburger, stew, and such delicacies as pig’s ears, pork kidneys, and beef brains.”

Starting the next morning, footwear would be subject to rationing, with each American entitled to three pairs of shoes per year.

Tthe reaction to rationing was instantaneous and frantic. Most shoe and department stores were closed on Sundays in that era, but in the few hours that remained before shoe rationing began, there was a rush on footwear at the handful of open stores. During the following week, after the order went into effect, the stampede continued, partly because some shoppers had misunderstood the rationing order to mean that shoes were already in short supply.

The apparel industry succeeded in blocking rationing plans from being implemented for any articles other than footwear, and that made it very difficult to control demand for clothing.48 But efforts to reduce resource consumption at the manufacturing stage were ambitious. For most clothing, the WPB established “square-inch limitations on the amount of material which may be used for all trimmings, collars, pockets, etc.,” while clothing was designed “to keep existing wardrobes in fashion” so that consumers would wear them longer. In discussing a WPB order regulating women’s clothing, the government publication Victory Bulletin observed, “The Basic Silhouette—termed the ‘body basic’ by the order—must conform to specified measurements of length, sweep, hip, hem, etc., listed in the order.” Such micromanagement even extended to swimwear, when a skimpier two-piece bathing suit was promoted for requiring less fabric.

Appliance manufacturing for civilian use was tightly restricted. From April 1942 to April 1943, no mechanical refrigerators were produced; that saved a quarter million tons of critical metals and other materials for use in war production. Starting in April 1943, sale of refrigerators, whether electric-run, gas-run, or a nonmechanical icebox type, was resumed; however, in order to be allowed to make a purchase, a household member had to attest on a federal form that “I have no other domestic mechanical refrigerator, nor do I have any other refrigerator equipment that I can use.” Stoves for heating and cooking were similarly rationed, requiring a declaration that the purchaser owned no functional stove. The OPA ruled that the 150,000 stovetop pressure cookers to be produced in 1943 would be allocated by County Farm Rationing Committees and that “community pools,” each comprising several families who agreed to the joint use of a pressure cooker, would receive preference. The WPB exerted its influence on production of radio tubes, light fixtures, lightbulbs, and even can openers. Bed and mattress production was maintained at three-fourths its normal level.

Reports noted, “Sacrificing metal-consuming inner springs, mattress manufacturers have reverted to the construction of an earlier period,” using materials such as cotton felt, hair, flax, and twine. The industry produced “women’s slips made from old summer dresses; buttons from tough pear-tree twigs; life-jacket padding from cattails; and household utensils from synthetic resins.”

In Britain, a series of “Limitations of Supplies” orders governed sales.

Soap was rationed because its production required fats, which had to be shared with the food and munitions industries.

The idea of clothes rationing was no more popular in Britain than it was in the United States. Prime Minister Winston Churchill didn’t like the idea at all, but neither he nor anyone else could come up with an alternative means to keep prices down and all Britons clothed. Apparel was given a page in the ration book originally reserved for margarine, which at the time was not being rationed. Annual allowances fluctuated between approximately one-third and two-thirds of average prewar consumption.

Price-controlled, tax-exempt “utility clothing” was made of fabric manufactured to precise specifications meant to ensure quality and long life. It was conceived in part by “top London fashion designers” and was not necessarily cheap. Yet it was generally well received because of its potential to delay one’s next clothing purchase. Utility plans eventually encompassed other textiles, shoes, hosiery, pottery, and furniture. Items had to be made to detailed specifications, and the number of styles was tightly limited.

Average people also got many opportunities to sit back and enjoy the public humiliation of well-heeled or politically powerful ration violators. In the summer of 1943, the OPA initiated proceedings against eight residents of Detroit’s posh Grosse Pointe suburb for buying meat, sugar, and other products without ration coupons. This gang of “socialites,” as they were characterized, included a prominent insurance executive, the wife of the president of the Detroit News, and the widow of one the founders of the Packard Motor Car Company who tried to buy four pounds of cheese under the table and got caught. In Maryland, the wife of the governor had to surrender her gas ration book after engaging in pleasure driving in a government vehicle.

In a column, Mathews demanded that “Washington start cracking down on the big fellows if you expect cooperation from the little fellows.” But it was Mathews himself who was arrested, on libel

\Wealthy Britons did not suffer much either under food rationing. Upscale restaurants could serve as much food as their customers could eat, and they were not subject to price controls. Such costly luxuries as wild game and shellfish were not rationed,

The rationing of goods at controlled prices provides a strong incentive for cheating, as the World War II example shows. For administering wartime rationing and price controls, the UK Ministry of Food had an enforcement staff of around a thousand, peaking in 1948 at over thirteen hundred. They pursued cases involving pricing violations; license violations; theft of food in transit; selling outside the ration system; forgery of ration documents; and, most prominently, illicit slaughter of livestock and sale of animal products. Illegal transactions accounted for 3 percent of all motor fuel sales and 10% of those involving passenger cars. Enforcement of rationing regulations and price controls by the ministry from 1939 to 1951 resulted in more than 230,000 convictions; the majority of offenders were retail merchants guilty of mostly minor offenses. An estimated 80% of the convictions resulted in fines of less than £5, and only 3 to 5 percent led to imprisonment of the offender. There were fewer problems involving quantity-rationed goods (for which consumers were paired up with a single retailer) than there were with rationing via points, which could be used anywhere. Zweiniger-Bargielowska writes that, although most people at one time or another made unauthorized purchases, the most corrosive effect of illicit markets was to subvert the ideal of “fair shares for all,” since it was only those better off who could afford to buy more costly contraband goods routinely.

In the United States, enforcement of price controls and rationing regulations made up 16% of the OPA’s budget. The agency identified more than 333,000 violations in 1944 alone but prosecuted just 64,000 people that year. Forty percent of prosecutions were for food violations, with the largest share for meat and dairy, and 17% were for gasoline. Along with flagrant overcharging, selling without ration-stamp exchange, and counterfeiting of stamps and certificates, businesses resorted to work-arounds: “tie-in sales” that required purchase of another product in addition to the rationed one, “upgrading” of low-quality merchandise to sell at the high-quality price, and short-weighting. As in Britain, the off-the-books meat trade got a large share of attention.

Illicit meat was sold for approximately double the legal price, and it tended to be the better cuts that ended up in illegal channels. Official numbers of hogs slaughtered under USDA inspection dropped 30% from February 1942 to February 1943, with the vanished swine presumably diverted into illegal trade. Off-the-books deals by middlemen were common, as was “the rustler, who rides the range at night, shooting animals where he finds them, dressing them on the spot, and driving away with the carcasses in the truck.” It wasn’t only meat that was squandered. Victory Bulletin warned, “Potential surgical sutures, adrenalin, insulin, gelatin for military films and bone meal for feeds are disregarded by the men who slaughter livestock illegally”; also lost was glycerin, needed for manufacturing explosives.

Retailers didn’t always play strictly by the ration book. A coalition of women’s organizations in Brooklyn urged Chester Bowles, director of the OPA, to prohibit shopkeepers from holding back goods for selected customers, demanding that all sales be first come, first served. But some OPA officials pointed out that such a policy would discriminate against working women who had time to shop only late in the day. Restaurants were free to serve any size portions they liked; however, if they decided to continue serving ample portions (for which they were allowed to charge a fittingly high price), they faced the prospect of having to close for several days each week when their meat ration ran out. Private banquets featuring full portions could be held with the permission of local rationing boards.

The ration stamps issued to a single household were not usually sufficient to purchase a large cut of meat such as a roast, and because stamps had expiration dates they could not be saved up from one ration period to the next in order to do so. Because consumers were required to present their own ration books in person when buying meat, announced the OPA, guests invited to a dinner party would have to buy their own meat and deliver it beforehand to the host cook—an awkward but workable solution if, say, pork chops were on the menu. However, if a single large cut such as a pot roast were to be served, the OPA noted, the host and invitees would have to “go to the butcher shop together, each buying a piece of the roast, and ask the butcher to leave it in one piece.”

The extension of rationing to bread in 1946–48, a move intended to ensure the flow of larger volumes of wheat to areas of continental Europe and North Africa that were threatened by famine, was highly controversial. People had come to depend on bread, along with potatoes, as a “buffer food” that helped feed manual workers and others for whom ration allowances did not provide sufficient calories. Rationing of the staff of life was unpopular from the start, even though allowances were adjusted to meet varying nutritional requirements and rations themselves were ample.

On November 15, Nixon asked all gasoline stations to close voluntarily each weekend, from Saturday evening to Sunday morning. As during World War II, a national allocation plan was put in place to ensure that each geographic region had access to adequate fuel supplies. In establishing allocation plans, the Federal Energy Office assigned low priority to the travel industry and, in an echo of World War II, explicitly discouraged pleasure driving. That same month, Nixon announced cuts in deliveries of heating oil—reductions of 15 percent for homes, 25% for commercial establishments, and 10%t for manufacturers—under a “mandatory allocation program.” The homes of Americans who heated with oil were to be kept six to ten degrees cooler that winter. Locally appointed boards paired fuel dealers with customers and saw to it that the limits were observed. Supplies of aviation fuel were cut by 15 percent. The national speed limit was lowered to 55 miles per hour. With Christmas approaching, ornamental lighting was prohibited. Finally, Nixon took the dramatic step of ordering that almost 5 billion gasoline ration coupons be printed and stored at the Pueblo Army Depot in Colorado, in preparation for the day when gas rationing would become necessary.

Here is how Time magazine depicted the national struggle for fuel during the 1973–74 embargo: The full-tank syndrome is bringing out the worst in both buyers and sellers of that volatile fluid. When a motorist in Pittsburgh topped off his tank with only $1.10 worth and then tried to pay for it with a credit card, the pump attendant spat in his face. A driver in Bethel, Conn., and another in Neptune, N.J., last week escaped serious injury when their cars were demolished by passenger trains as they sat stubbornly in lines that stretched across railroad tracks. “These people are like animals foraging for food,” says Don Jacobson, who runs an Amoco station in Miami. “If you can’t sell them gas, they’ll threaten to beat you up, wreck your station, run over you with a car.” Laments Bob Graves, a Lexington, Mass., Texaco dealer: “They’ve broken my pump handles and smashed the glass on the pumps, and tried to start fights when we close. We’re all so busy at the pumps that somebody walked in and stole my adding machine and the leukemia-fund can.”

President Gerald Ford laid out a plan to reduce American dependence on imported oil by imposing tariffs and taxes on petroleum products. His plan was met with almost universal condemnation. A majority of Americans polled said they would prefer gasoline rationing to the tax scheme. Time agreed, arguing that rationing would have three crucial qualities going for it—directness, fairness, and familiarity—and adding that “support for rationing is probably strongest among lower-income citizens who worry most about the pocketbook impact of Ford’s plan.

The federal government, he said, should challenge Americans to make sacrifices, and its policies must be fair, predictable, and unambiguous. But, he warned, “we can be sure that all the special-interest groups in the country will attack the part of this plan that affects them directly. They will say that sacrifice is fine as long as other people do it, but that their sacrifice is unreasonable or unfair or harmful to the country. If they succeed with this approach, then the burden on the ordinary citizen, who is not organized into an interest group, would be crushing.” He was right. Critics in both the private and public sectors rejected Carter’s characterization of the energy crisis as the “moral equivalent of war” and viewed any discussion of limits, conservation, or sacrifice as a threat to the economy. Opponents then mocked his call to arms by abbreviating it to “MEOW,” while Congress simply ignored Carter’s warnings and avoided taking any effective action on energy.

Ground zero for the gas shortages of 1979 was California. The state imposed rationing on May 6, allowing gas purchases only on alternate days: cars with odd license-plate numbers could be filled on odd days of the month and even numbers on even days. Several other states followed suit, but that move alone didn’t relieve the stress on gas stations. Many station attendants refused to fill tanks that were already half full or more. That first Monday morning, many drivers who woke up early to allow time to buy gas on the way to work instead found empty, locked cars already standing in long lines at the pumps. The cars had been left there the previous evening by drivers who then walked or hitchhiked back to the station in the morning. Two Beverly Hills attorneys tied their new rides—a pair of Arabian horses—to parking meters outside their office as they prepared to petition the city to suspend an ordinance against horse riding in the streets. The National Guard was called out to deliver gas to southern Florida stations. A commercial driver hauling a tankful to a Miami station found a line of 25 cars following him as if, he later said, he’d been “the Pied Piper.” In some cities, drivers were seen setting up tables alongside their cars in gas lines so the family could have breakfast together while waiting to fill the tank.

One of the worst incidents occurred in Levittown, Pennsylvania, where a crowd of 1500 gasoline rioters “torched cars, destroyed gas pumps, and pelted police with rocks and bottles.” A police officer responded to a question from a motorist by smashing his windshield, whacking the driver’s son with his club, and putting the man’s wife in a choke hold. In all, 82 people were injured, and almost 200 were arrested. Large numbers of long-haul truckers across the nation went on strike that summer, parking their rigs. Some blockaded refineries, and a few fired shots at non-striking truckers. The National Guard was called out in nine states, as “the psychology of scarcity took hold.” A White House staffer told Newsweek, “This country is getting ugly.

During World War II, gasoline scarcity was far worse in some regions than in others. But increasing desperation in the nation’s dry spots prompted talk of rationing even in conservative quarters. The columnist George F. Will observed, “There are, as yet, no gas lines nationwide. If there ever are, the nation may reasonably prefer rationing by coupon, with all its untidiness and irrationality, to the wear and tear involved in rationing by inconvenience.” A New York Times–CBS News poll in early June found 60 percent of respondents preferring rationing to shortages and high prices.

Carter wanted the government to have the ability to ration gas, thereby freeing up supplies that could then go to regions that were suffering shortages. Thanks largely to the oil companies’ fierce opposition, Congress refused to pass standby rationing in May, but support for the idea continued to grow.

Most of his policy recommendations were again focused on conservation. His most specific move was asking Congress once again for authority to order mandatory conservation and set up a standby gasoline rationing system. Of the five thousand or so telegrams and phone calls received by the White House in response to that speech, an astonishing 85% were positive. Carter’s approval jumped 11 points overnight. The next day, he spoke in Detroit and Kansas City, both times to standing ovations. But Carter was still being vague about what, specifically, Americans were supposed to do. Meanwhile, renewed political wrangling on other issues and a drop in gas prices drained away the nation’s sense of urgency over energy. The deeper problems had not gone away, but without the threat of societal breakdown that had so alarmed the public and stirred Carter to bold oratory, the incentive to take action vanished.

Despite a 28% improvement in vehicle fuel economy, America’s total annual gasoline consumption has increased 47% since 1980, with the consumption rate per person 10% higher today than in 1980. Had there been a 20% gasoline shortfall at the start of the 1980s, triggering Congress’s gas-rationing plan, and had we managed to hold per-capita consumption at the rationed level for the next 30 years (taking into account the rate of population increase that we actually experienced), we would have saved 800 billion gallons—equal to about six years of output from U.S. domestic gasoline refiners. That’s a lot in itself, but such long-term restraint would have caused a chain reaction of dramatic changes throughout the economy, changes so profound that America would probably be a very different place today had rationing been instituted and had it continued. That didn’t happen. Instead, the U.S. economy focused again on developing new energy-dependent goods and services.

The clearest expression of the current goals of our foreign policy came in an address to the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro by President George H.W. Bush, a year after the first Persian Gulf war. There he announced to the world that “the American way of life is not negotiable,” signaling that the country had changed profoundly since the day almost exactly fifty years earlier when Harold Ickes had declared that patriotic citizens would never risk the lives of their soldiers to preserve “motoring as usual.”

According to calculations by Vaclav Smil of the University of Manitoba, the human economy has already reduced the total weight of plant biomass on Earth’s surface by 45%. About 25% of each year’s plant growth worldwide, and a similar proportion of all freshwater flowing on Earth’s surface, is already being taken for human use. If you could put all of our livestock and other domestic animals on one giant scale, they would weigh 25 times as much as Earth’s entire dwindling population of wild mammals. In 2009, a group of 29 scientists from seven countries published a paper in which they defined nine “planetary boundaries” that define a “safe operating space” for humanity. If we cross those boundaries and don’t pull back, they concluded, the result will be catastrophic ecological breakdown. Given the uncertainties involved in any such projections, they proposed to set the limits not at the edge of the precipice but at some point this side of it, prudently leaving a modest “zone of uncertainty” as a buffer. The boundaries were defined by limits on atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration; air pollutants other than carbon dioxide; stratospheric ozone damage; industrial production of nitrogen fertilizer; breakdown of aragonite, a calcium compound that’s an indicator of the health of coral and microscopic sea organisms; human use of freshwater; land area used for cultivation of crops; species extinction; and chemical pollution. The group noted that we have already transgressed three of the limits: carbon dioxide concentration, species extinction, and nitrogen output. Furthermore, they concluded, “humanity is approaching, at a rapid pace, the boundaries for freshwater use and land-system change,” while we’re dangerously degrading the land that is already sown to crops.

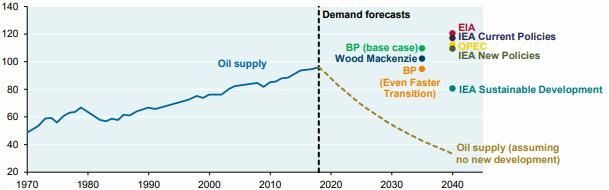

The International Energy Agency (IEA) concludes that extraction of conventional oil peaked in 2006, but that with increases in mining of oil from unconventional deposits like the tar sands of Canada, the plateau will bump along for decades.

Demand for gas may rise even faster than that. It seems that everyone these days is looking to natural gas to bail the world out of all kinds of crises: big environmental groups urge that it be substituted for coal to reduce carbon emissions; the transportation industry wants to substitute it for increasingly costly oil by burning it directly, converting it to liquid fuel, or by feeding power plants that in turn will feed the batteries in electric cars; enormous quantities will be consumed in the process of extracting oil from tar-sand deposits; and high-yield agriculture requires increasing quantities of nitrogen fertilizer manufactured with natural gas.

In the near term, the process of hauling enough rock phosphate, lime, livestock manure, or even human waste to restore phosphorus-deficient farm soils will be burdened by increasing transportation costs. Then there are tractors, 4.2 million of them on farms and ranches in the United States alone. Field operations on almost all farms in America, including organic farms, are heavily dependent on diesel fuel or gasoline. Finally, the farm economy supports a much larger off-farm food economy, one that is heavily dependent on fossil energy. Now we are asking the industrial mode of agriculture, with its own low energy efficiency, to supply not only food and on-farm power but also billions of gallons of ethanol and biodiesel for transportation.

If enough good soils and waters are to be maintained to support that life, the currently wasteful means of using water and growing food must be not just adjusted but transformed. Until that happens, the interactions among energy, water, and food will come to look even more like a game of rock-paper-scissors. Energy shortages or restrictions can keep irrigation pumps, tractors, and fertilizer plants idle or make food unaffordable.

Current methods for producing food are huge energy sinks and major contributors to greenhouse-gas warming, while the conversion of food-producing land to substitute for mineral resources in providing fuel, fabric, rubber, and other industrial crops will accelerate soil degradation while contributing to wasteful energy consumption.

The next best course is to make it later rather than sooner by leaving fossil fuels in the ground longer. But can economies resist burning fossil fuels that are easily within reach? Might even renewable energy sources be harnessed to the task of obtaining much more potent and versatile fossil energy? That is already happening in various parts of the world, including the poverty-plagued but coal-rich state of Jharkhand in India. Strip mining there is pushing indigenous people off their land, ruining their water supply, and driving them to desperate means of earning an income. Every day for the past decade, it has been possible to witness a remarkable spectacle along a main highway between the coal-mining district of Hazaribagh and the state capital, Ranchi: men hauling coal on bicycles. Each bike, with its reinforced frame, supports up to four hundred pounds of coal in large sacks. The men, often traveling in long convoys, push the bicycles up steep ridges and sometimes stand on one pedal to coast down. Their cargo has been scavenged from small, shallow, village-dug mines, from government-owned deposits that are no longer economically suitable for large-scale mining, or from roadsides where it has fallen, they say, “off the back of a truck.” Hauling coal the forty miles from Hazaribagh to Ranchi takes two days, and the men make the round-trip twice a week. These “cycle-wallahs” travel roads throughout the region, delivering an estimated 2.5 million metric tons of coal and coke annually to towns and cities for cooking, heating, and small industry.

If scarcity, either absolute or self-imposed, becomes a pervasive fact of life, will rationing no longer be left to the market? Will more of it be done through public deliberation? Ask ecologists and environmentalists that question today, and you frequently hear that quantity rationing is coming and that we should get ready for it. David Orr, a professor of environmental studies and politics at Oberlin College in Ohio and a leading environmental thinker, believes that “one way or another we’re going to have rationing. Rationing goes to the heart of the matter.” Although “we assume that growth is humanity’s destiny and that markets can manage scarcity,” Orr believes that “letting markets manage scarcity is simply a way of not grappling with the problem.” And because “there is no question that rationing will happen,” he says the key question is how. “Will it be through growth in governance, either top-down or local, or will we let it happen ‘naturally,’” through prices? The latter course, Orr believes, would lead to chaos.36 Likewise, Fred Magdoff, co-author (with John Bellamy Foster) of What Every Environmentalist Needs to Know About Capitalism, among other books, sees rationing as very likely necessary in any future economy that takes the global ecological crisis seriously.

He says there is no escaping the problem of distribution: “There is rationing today, but it’s never called that. Allocation in our economy is determined almost entirely in one of two ways: goods tend to go to whoever has the most money or wherever someone can make the most profit.” As an alternative, he says, rationing by quantity rather than ability to pay “makes sense if you want to allocate fairly. It’s something that will have to be faced down the line. I don’t see any way to achieve substantive equality without some form of rationing.” But, Magdoff adds, “there’s a problem with using that terminology. There are certain ‘naughty’ words you don’t use. ‘Rationing’ is not considered as naughty as ‘socialism,’ but it’s still equivalent to a four-letter word.”37

Ask almost any economist today, however, and you will learn that non-price rationing simply doesn’t work and should be avoided. For example, Martin Weitzman, at Harvard University, who developed some of the basic theory of rationing decades ago, takes the view that “generally speaking, most economists, myself included, think that rationing is inferior to raising prices for ordinary goods. It can work for a limited time on patriotic appeal, say during wartime. But without this aspect, people find a way around the rationing.” He adds that rationing would also “require a large bureaucracy and encounter a lot of resistance. I am hard-pressed to think of when rationing and price controls would be justified for scarce materials.” Others see rationing as unworkable not only for technical reasons but simply because people in affluent societies today cannot even imagine life under consumption limits. Maurie Cohen has little confidence that residents of any industrialized society would accept comprehensive limits on consumption because, in his view, “following a half century of extraordinary material abundance, public commitments to consumerist lifestyles are now more powerfully resolute.”39 David Orr agrees that prospects for consumption restraints in America today are dim at best: “We have to reckon with the fact that from about 1947 to 2008 we had a collision with affluence, and it changed us as a people. It changed our political expectations, it changed us morally, and we lost a sense of discipline. Try to impose a carbon tax, let alone rationing, today and you’ll hear moaning and groaning from all over.”40

In theory, shortages are always temporary. As the price of a scarce good rises, fewer and fewer people are able and willing to buy it, while at the same time producers are stimulated to increase their output. The price stops rising when demand has been driven low enough to meet the rising supply. If for whatever reason (often because of absolute scarcity, as with Yosemite campsites) the price is not allowed to rise to the heights required to bring demand and supply into alignment, and there is no substitute product that can draw away demand, the good is apportioned in some other way. At that point, nonprice rationing, often referred to simply as “rationing,” begins.

With basic necessities as much as with toys, rationing by queuing tends to create not buzz but belligerence. Dreadful memories of rationing by queuing—like the lines that formed at gas stations across America and outside bakeries in the Soviet Union in the 1970s—are burned into the memories of those who lived through those times; few regard such methods of allocation as satisfactory when it comes to essential goods.

Weitzman then summarized the case in favor of rationing: The rejoinder is that using rationing, not the price mechanism, is in fact the better way of ensuring that true needs are met. If a market clearing price is used, this guarantees only that it will get driven up until those with more money end up with more of the deficit commodity. How can it honestly be said of such a system that it selects out and fulfills real needs when awards are being made as much on the basis of income as anything else? One fair way to make sure that everyone has an equal chance to satisfy his wants would be to give more or less the same share to each consumer independent of his budget size. Acknowledging that arguments both for and against rationing of basic needs “are right, or at least each contains a strong element of truth,” Weitzman went on to demonstrate mathematically how rationing by price performs better when people’s preferences for a commodity vary widely but there is relative equality of income. Rationing by quantity appeared superior in the reverse situation, when there is broad inequality of buying power and demand for the commodity is more uniform (as can be the case with food or fuel, for example).45 In a follow-up to Weitzman’s analysis, Francisco

Rivera-Batiz showed that rationing’s advantage increases further if the income distribution is skewed—that is, if the majority of households are “bunched up” below the average income while a small share of the population with very high incomes occupies the long upper “tail” of the distribution. Rivera-Batiz concluded that quantity rationing “would work more effectively (relative to the price system) in allocating a deficit commodity to those who need it most in those countries in which economic power and income are concentrated in the hands of the few.

Writing back in the early days of World War II, the Dutch economist Jacques Polak had come to a similar conclusion: that rationing had become necessary because even a small rise in price can make it impossible for the person of modest income to meet basic needs, while in a society with high inequality there is a wealthy class that can “push up almost to infinity the prices of a few essential commodities.” Therefore, he stressed, it is not shortages alone that create the need for rationing with price controls; rather, it is a shortage that occurs in a society with “substantial inequalities of income.”

The burden of consumption taxes weighs most heavily on people in lower-income brackets. It has been suggested that governments can handle that problem by redistributing proceeds from consumption taxes in the form of cash payments to low-income households. But determining the size of those payments is no easier than finding the right tax rate; furthermore, means-tested redistribution programs often come to be seen by more affluent non-recipients as “handouts” to undeserving people and are therefore more politically vulnerable than universal programs or policies. Weitzman has also observed that problems always seem to arise when attempts are made to put compensation systems into practice. The argument that the subsidies can blunt the impact of the taxes, he says, “is true enough in principle, but not typically very useful for policy prescriptions because the necessary compensation is practically never paid.”

Eighteen years later, continuing his examination of the potential of taxes and income subsidies for addressing inequality, Tobin observed that redistributing enough income to the lower portion of the American economic scale through a mechanism like the “negative income tax” being contemplated by the Nixon administration at the time (which would have provided subsidies to low-income households much like today’s Earned Income Tax Credit) would require very high—and, by implication, politically impossible—tax rates on higher incomes.

With rationing by quantity, people or households use coupons, stamps, electronic credits, or other parallel currencies that entitle them to a given weight or measure of a specific good—no more, no less—over a given time period. Normally, as was the case in World War II–era America and Britain, rationed goods or the credits to obtain them may be shared among members of a household but may not be sold or traded outside the household. The plan may be accompanied by subsidies and/or price controls.

“Rationing in time,” cannot ensure that savings of the resource will be proportional to the length of time for which supply is denied. For example, consumption doesn’t fall by half when alternate-day lawn-watering restrictions are in force, because people can water as much as they like on their assigned days.

Unlike straight rationing, quantity rationing by points cannot guarantee everyone access to every item in the group of rationed items, but it can ensure a fair share of consumption from a “menu” of similar items. Points, like all ration credits, are a currency. Every covered item requires payment in both a cash price and a point price. But points differ from money in that every recipient has the same point “income,” which does not have to be earned; points can be spent only on designated commodities; point prices are not necessarily determined by supply and demand in the market; and trading in points is usually not permitted.

The range of goods covered by a given point scheme could in theory be as narrow as it was with canned goods during World War II or as broad as desired—if, for example, there were a point scheme covering all forms of energy, with different point values for natural gas, gasoline, electricity, etc.

The values of items in terms of points can be set according to any of several criteria. In the case of wartime meat, items with higher dollar prices also tended to be the ones assigned higher point values (for a time in Britain, dollar and point values were identical), but for other types of products, an item’s point value might reflect the quantity of a scarce resource required to produce it—or, as we will see, the greenhouse-gas emissions created during its manufacture, transport, and use. The more closely point values are adjusted to reflect the level of consumer demand that would exist without rationing, the less they interfere with functioning of the market.

Among people with differing preferences, there will be winners and losers.

If only a few items are restricted, people take the extra money that they would otherwise have spent on additional rationed goods and spend it on non-rationed ones, driving up their prices. If price controls are then extended to other goods without rationing them, demand for those goods shoots up even higher, and stocks are further depleted. These goods are then brought into the rationing scheme, thereby extending it to larger and larger numbers of essential goods.

But what about nonessential goods, such as swimming pools or rare wines? If the main concern is fair access to necessities, there seems little reason to ration nonessentials. If wealthy people, prohibited from buying as much gasoline or food as they would like, use their increased disposable income to bid up the prices of luxuries, is too little harm done even to worry about? Maybe, but it would depend on the motive for rationing. If the goal is to reduce total resource consumption, the prices of vintage wines or rare books might be left to the market, while the construction of swimming pools would be restricted.

As an alternative to a vast, complex system of quantity-rationing schemes for many products, Kalecki proposed simply to ration total spending. Each person would be permitted expenditures only up to a fixed weekly limit in retail shops, with the transactions tracked through coupon exchange. Up to that monetary limit, families could buy any combination of goods and quantities, as long as their total per-person spending stayed under the limit. No such system of “general” or “expenditure” rationing has ever been adopted, but during and after the war, several British and American economists examined the possible consequences of employing it during some future crisis. Once again, they realized, income inequality would complicate things. If the spending ceiling was the same for everyone, as was proposed, then lower-income families could spend their entire paycheck and still have coupons left over. Such families might be tempted to sell their excess coupons to people who had more cash to spend than their coupon allotment would allow. Some economists worried that that would not only stimulate unwanted demand but violate the “fair shares for all” principle.56 It was Kalecki who finally proposed a workable solution: that the government offer to buy back any portion of a person’s expenditure allowance that the person could not afford to use. For example, if the expenditure ration were £30 but a family had only £10 worth of cash to spend, they could, under Kalecki’s proposal, sell one-third of their allowance back to the government and be paid £10 in cash. That could be added to the £10 they had on hand, and they could spend it all while staying within the limit imposed by their £20 worth of remaining ration coupons.

The government buyback system would be intended to prevent the exploitation of the worse off by the better off and ensure a firm limit on total consumption, creating a “fairly comprehensive, democratic, and elastic system of distributing commodities in short supply,” and it would provide an automatic benefit to low-income families without an artificial division of the population into “poor” and “non-poor” categories. Well-to-do families would tend to accumulate savings under expenditure rationing, and Kalecki urged that those savings be captured by the government through an increase in upper-bracket income tax rates. That would not only curb inflation, it could also help pay for the coupon buyback scheme. Kalecki’s idea of allowing people to return ration credits for a refund rather than sell them to others has since been suggested as a feature of future carbon-rationing schemes. Quantity rationing of specific goods and general

In a report written for the U.S. National Security Resources Board in 1952, the economist Gustav Papanek looked back at the wartime discussion of expenditure rationing and saw plenty of deficiencies when he compared the concept with that of straight rationing of individual goods. He noted that if the same spending ceiling were applied to everyone, it could mean a dramatic change in lifestyle for the wealthy, who would probably push back hard against such restrictions. As one of many examples, he cited people with larger houses, who would plead that they had much higher winter heating bills and that allowances would have to be made. Nevertheless, a uniform spending ceiling would be necessary, wrote Papanek, because allowing those with larger incomes to spend more money “not only would make inequality of sacrifice in wartime evident, but would also place upon it the stamp of government approval.”

In many countries, a large portion of the supply of food, water, cooking fuel, or other essentials is subsidized and rationed by quantity, while the remaining supply is traded on the open market. Such two-tier systems provide a floor to ensure access to the necessary minimum but have no ceiling to contain total consumption. Some also treat different people or households differently by, for example, steering subsidized, rationed goods toward lower income brackets. And in some, there is the option of allowing the barter or sale of unused ration credits among consumers and producers. Such markets were proposed as part of Carter’s standby gas rationing plan, and they have been included in more recent proposals for gas rationing and for limiting greenhouse-gas emissions.

The consequences of rationing can be difficult to predict, but one thing is certain: nobody wants to be told what we can and cannot buy. There will be cheating. There are always people—often many people—who want to buy more of a rationed product than they can obtain legally; otherwise, there would be no need to ration it.

Widespread circumvention of regulations poses a dilemma. On the one hand, Cohen wrote, attempts to enforce total compliance are “ineffectual in the short term and counterproductive in the long term,” while on the other, lax enforcement “will lead to the erosion of public support.” Cohen concluded that “there is no easy solution to this dilemma other than agile and adept management.

Evasion of wartime price controls and rationing was less extensive in Britain than in the United States. Conventional wisdom long held that the difference could be explained by a greater respect for government authority among British citizens, reinforced by their more immediate sense of shared peril (the “Dunkirk spirit”). But an analysis of wage and price data before, during, and after the war shows that the most important factor was the British government’s tighter and more comprehensive control of supply and demand. Enforcement in both countries went through mid-war expansion in response to illicit activity, but key measures taken by the British—complete control of the food supply; standardization of manufacturing and design in clothing, furniture, and other products; concentration of manufacturing in a smaller number of plants; the consumer–retailer tie; and rationing of textiles and clothing—were not adopted in America, where industry opposition to such interference was stronger. The British also invested much more heavily in the system. In 1944, with rationing at its peak in both countries, British agencies were spending four and a half times as much (relative to GDP) as their American counterparts on enforcement of price controls. They were also employing far more enforcement personnel and filing eight times as many cases against ration violators, relative to population.

The differential impact of rationing and underground markets on economic classes should not be ignored. Theory says that the rich are better off in a pure market economy, while those with the lowest incomes are better off in an economy that incorporates rationing; however, the poor benefit even more under rationing (whether it’s by coupons or queuing) that is accompanied by an underground market, because secure access to necessities is accompanied by some flexibility in satisfying family needs. This is thought to be one of the many reasons that there was such widespread dissatisfaction with the conversion from a controlled economy with illegal markets to an open, legal market economy in the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe in the 1990s.

Ration cards, books, stamps, and coupons are not only clumsy and inconvenient; they invite mischief as well. Some of the biggest headaches for past and current systems have involved the theft, sale, and counterfeiting of ration currency. Some have suggested that in the future it would be easier to head off cheating by using technologies such as smart cards and automatic bank debits that were not available during previous rationing eras.

Several countries are currently pursuing electronic transfers for their food-ration systems. Of course, electronic media are far from immune to outlaw trading; consumers, businesses, and governments have long battled a multibillion-dollar criminal market that exploits credit and debit cards, ATMs, and online vulnerabilities. Were rationing mechanisms added to that list of targets, enforcers would be drawn into similar kinds of cat-and-mouse games with hackers and thieves. Cohen argues that while smart cards and similar technologies can reduce administrative costs and red tape, they cannot eliminate cheating and that it is unrealistic to expect “high-tech rationing” to wipe out evasion and fraud. It will still be necessary, he predicts, “to use customary enforcement tools to limit the corrosive effects of unlawful practices.”64 Some have

No law is ever met with total compliance, but there are many examples of laws and regulations that appear to be accomplishing their goals despite routine violations. Compare limits imposed by rationing to speed limits. Around the world it is common for a large share of motorists to be exceeding posted speed limits at any one time. Like the majority of wartime rationing violators, who dipped only lightly into the underground market, most drivers fudge just a few miles per hour. A relatively small proportion of drivers break the limit by ten miles per hour or more, and a still smaller percentage of speeders are ticketed; nevertheless, speed limits succeed in preventing accidents and fatalities. Existence of a speed limit is cited by drivers as an important reason for driving more slowly than they otherwise would, whereas concern about pollution or fuel consumption is not. Also relevant to a discussion of rationing