Mike Turner sprayed herbicide recently on the weed Salvinia molesta on Caddo Lake near Uncertain, Tex. The weed suffocates all life beneath it. The furry green invader from South America is threatening to smother the labyrinthine waterway, the largest natural lake in the South, covering about 35,000 acres and straddling Texas and Louisiana. Blumenthal, R. July 30, 2007. In East Texas, Residents Take On a Lake-Eating Monster. New York Times. Photo credit: Michael Stravato.

[ The 2011 House of Representatives hearing below is a discussion of how to control salvinia.

We spend about $135 billion on invasive species a year – what will happen when the fossil energy to remove them is no longer available? It’s likely the carrying capacity of vast regions of the country will be lowered as irrigation canals fill up with giant salvinia and other invasive water plants, fishing in lakes impossible as oxygen levels plummet and kill fish, as well as becoming unnavigable from thick mats of salvinia and other invasive water plants. Salvinia also provides great habitat for disease-bearing mosquitoes, further lowering carrying capacity.

A quick search of the internet turned up these as some of the most invasive plants and animals: Asian Carp, Asian citrus psyllid, Asian Long-horned beetle, Asian-tiger mosquito, Burmese Python, Canada geese, Cane toad, Cotton Whitefly, Cownose Ray, Emerald ash borer, Eurasian watermilfoil, Hemlock wooly adelgid, Kudzu, Lionfish, Mountain pine beetles, multiflora rose, Nile perch, Nutria, privet, Rabbits, Rats, Snakehead fish, spiny waterflea, starlings, Sudden oak death, Tamarisk (salt cedar), Tumbleweed, vine mealybugs, Zebra mussels.

For all of the United States 1,230 invasive PLANT species go here, and www.invasive.org has 2,892 species listed

Alice Friedemann www.energyskeptic.com author of “When Trucks Stop Running: Energy and the Future of Transportation”, 2015, Springer and “Crunch! Whole Grain Artisan Chips and Crackers”. Podcasts: KunstlerCast 253, KunstlerCast278, Peak Prosperity]

Summary: why you should be afraid of Giant salvinia (Salvinia molesta):

- The United States Geological Survey calls Salvinia molesta one of the world’s most noxious aquatic weeds, with an ability to double in size every two to four days and cover 40 square miles within three months, suffocating all life beneath.

- Giant salvinia reduces the oxygen in the water, which increases water treatment requirements and costs. The 1-meter-mats clog waterways and block sunlight from reaching other aquatic plants below the surface, reducing the amount of oxygen in the water. As these plants die and sink to the bottom where decomposer organisms use up even more oxygen in the water. The mats also impede the natural exchange of gases between the water and the atmosphere, which can lead to stagnation of the water body. Ultimately, these processes will kill all plants, aquatic insects, and fish living below the mats. There is also evidence that salvinia mats cause acidification of lakes and ponds. If left untreated, giant salvinia can completely take over and destroy the ecological system of any freshwater body.

- Decreases floral and faunal diversity and impacts threatened and endangered species

- Increases mosquito breeding habitat for species that are known to transmit encephalitis, dengue fever, malaria, and rural filariasis or elephantiasis.

- Water management structures are damaged or rendered useless, water quality is decreased, it threatens property values, boating and commercial navigation is impeded, intakes for municipal drinking water or industrial facilities are clogged, and recreational uses such as fishing, waterfowl hunting, paddling, or swimming are stopped. It can clog and burn up boat motors.

- They’re useless for biofuels because they are 95% water, leaving just 5% of dried out salvinia to use for cellulosic fuels. The economics of harvest are poor – you’re moving a lot of water weight onshore and then transporting it inland to a processing plant. Other countries that have tried to convert aquatic plants to biofuels have been unsuccessful. It’s hard to even harvest them with mechanical harvesters because the mats are so huge.

- It can prevent navigation in slow-moving rivers (but not in fast flowing waterways). For example, the Sepik River in Papua New Guinea is huge, but very slow moving, and covered with salvinia. Whole villages were moved because the people couldn’t get into the river to fish.

- Florida water hyacinths pile up against bridges and take them out, it’s possible salvinia will do the same

- Hurricanes can spread salvinia widely to new areas

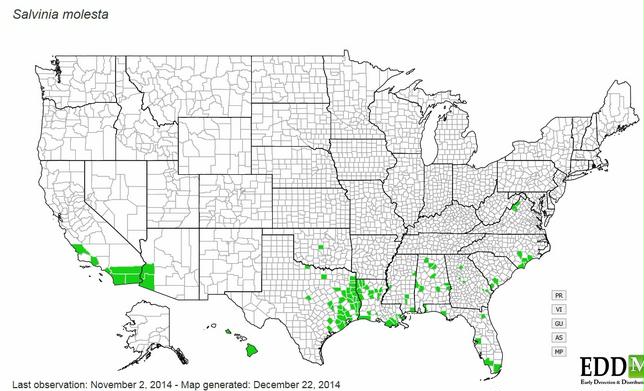

- In the United States, it is now found in at least 90 localities and is especially troublesome in southern states including Texas, North and South Carolina, Louisiana, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi and west into Arizona and California. It is established in at least 11 states, and has the potential to devastate freshwater habitats in 20 states.

- Its range is increasing worldwide and is now causing significant problems in over 20 countries including Australia, New Zealand, Fiji, the Philippines, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Papua, New Guinea, the Ivory Republic, Ghana, Zambia, Kenya, Namibia, Botswana, South Africa, Madagascar, Columbia, Guyana, and several Caribbean countries (including Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Trinidad). This list increases yearly.

- Intakes for industrial water or municipal drinking water get clogged. Cross Lake now has giant salvinia in it, and that’s where the City of Shreveport gets their water from.

- Habitat is destroyed for air-breathing animals like otters, diving birds, turtles and frogs, which cannot penetrate the mat.

- Caddo Lake is one of only 27 wetlands in the United States recognized by the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands. The bald cypress forests of Caddo Lake, including trees as old as 400 years, host one of the highest breeding populations of wood ducks as well as prothonotary warblers and other neotropical birds. The forests and wetlands of Caddo Lake are critical for migratory bird species within the Central Flyway, including tens of thousands of migrating waterfowl that utilize Caddo Lake (and other nearby lakes) as resting and feeding grounds. Giant Salvinia forms dense floating mats that prevents growth of natural vegetation, a food source for waterfowl, and eliminate open water for waterfowl to rest on.

Summar: Why giant salvinia is so hard to kill:

- Can live up to a couple of weeks out of water

- It’s hard to kill with chemical sprays because of tiny, white hairs that capture herbicides just above the plant’s surface

- The best chemical spray is Galleon that kills by saturation and must remain in the water 60 to 90 days. But if it rains or floods, the chemical is diluted and doesn’t work. And it’s expensive — $1,850 per gallon.

- The rapid growth rate of salvinia allows it to easily outpace the application of chemicals.

- Using chemicals to kill salvinia’s thick 1-meter mats is like peeling an onion. You have to peel off layer after layer after layer after layer. It’s expensive and requires a lot of tenacity to go out and spray the same body of water every two weeks for the rest of your life.

- No one knows what effect massive amounts of herbicides will have on wildlife and fish, much less the humans that consume them…and may be as detrimental (or more so) than leaving the plants in place. Chemicals include: diquat, glyphosate, fluridone, carfentrazone-ethyl, penoxsulam and flumioxazin.

- Hard to kill with chemicals because of the ability of salvinia to re-grow from small buds or plants that are missed during chemical application, especially in backwater coves where overhanging vegetation can hide small plant populations or where plant growth is dense and underlying layers are protected from surface sprayed herbicides. These plant fragments can be smaller than 1/4 inch. It also hides under water hyacinths, alligatorweed, and hydrilla.

- Chemicals might aid salvinia, in that invasive species take advantage of disrupted ecosystems and have a much harder time if every niche is filled with a native species in a healthy ecosystem. Chemicals disrupt ecosystems and degrade habitat, priming the area for even more invasion.

- Though susceptible to saltwater, it takes too much to reach the level you need. Before you kill the salvinia, you’ll be killing the cypress trees and the bass and the freshwater fish.

- Fish and animals won’t consume giant salvinia because it has a metabolic inhibitor (thiamine inhibitor) that is toxic. So it can’t be used for cattle feed either.

- The Brazilian salvinia weevils that can kill/reduce salvinia die in cold weather

- Biological control with weevils can take several years and may not be particularly effective in the more northern extreme of salvinia’s distribution

- It’s possible that some or all of the chemicals will kill or reduce the weevil population

- Salvinia weevils are about the only weevil that doesn’t fly, so someone to hand move them to nearby bodies of water, which is very labor intensive.

- But weevils will try to swim to another pond, but in south Louisiana, they’re all consumed by fire ants, another invasive species—and none of the weevils made it more than about 20 feet from the pond.

- It spreads easily: it can hitchhike on boats to other lakes and waterways. All it takes is one alligator, one nutria or other wildlife, to move from an infested water body into an area where giant salvinia hasn’t yet taken root, and the spread continues.

- Draining or lowering lake levels to dry out salvinia doesn’t work because there are massive deposits of nutrient laden biomass on the lake bottom. When the lake was refilled this decomposing biomass provided a ready source of nutrients to perpetuate the growth of more plants. and scattered the salvinia throughout the water body making treatment even more difficult

- Even flamethrowers can’t kill it

- Even frozen in ice doesn’t kill it because the mats are so thick the salvinia in the middle survives

- It can’t be fenced off or booms deployed until winter comes to kill it off

- The only solution is physically harvest and remove the biomass and limit herbicide spraying to only those areas that are not accessible to harvesting.

- If Salvinia is pushed over a dam into a river, no harm is done if the river keeps flowing rapidly, but slow moving rivers and oxbows are at risk.

- It keeps getting fed by nutrient runoff from agriculture, which also has created 9600 square miles of dead zone in the Gulf

- Spraying can be incredibly difficult. Many areas are also inhabited by the iconic cypress tree, making it incredibly difficult for spray crews and their boats to access parts of these infested water bodies. When the tree loses its leaves each year, the debris further fuels the degradation of the aquatic habitat. While we advocate for moderate tree removal, this is both expensive and, at times, unpopular with the public.

- Giant salvinia cannot simply be eradicated. This deft plant is far too integrated into our environment to kill off

House 112-47. June 27, 2011. Giant Salvinia: How do we protect our ecosystems? U.S. House of Representatives. 88 pages.

Excerpts:

JOHN FLEMING, LOUISIANA. The purpose of today’s hearing is to obtain testimony on efforts to control and eradicate one of the worst invasive weeds in the world. Giant salvinia is a free-floating aquatic fern, native to South America and introduced to the United States by the water garden industry. Since then, giant salvinia has proven to be an aggressive invader that can double in size in four to 10 days under favorable growing conditions, and its expanded mats of vegetation degrade fishing habitat, decrease water quality, create unsafe boating and fishing access and threaten property values. Caddo Lake was first infested with giant salvinia in 2006 and within two years the plant expanded its coverage on the lake from less than two acres to more than 1,000 acres. Efforts conducted to control giant salvinia thus far have yielded moderate success but have not completely eradicated the species from the lake.

Native to Brazil, giant salvinia, the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department has recently issued a publication that states invasives can kill a lake, and giant salvinia is the worst of the lot. Dr. Randy Westbrooks of the United States Geological Survey has noted that giant salvinia plants do not die quickly. In fact, they can live a few days or even a couple of weeks out of water.

There’s been a comprehensive effort to control and eradicate giant salvinia. These efforts have saved lakes from becoming giant dead zones. The fight to eradicate giant salvinia will be a long and arduous battle. Once an invasive species has become established, it is difficult, if not impossible, to completely remove it. There’s no silver bullet to kill giant salvinia. We will continue to contain this invasive species by utilizing a number of different strategies, including simple things like making absolutely sure that once a boat is removed from the lake, the boat owner does not allow giant salvinia to hitchhike home.

LOUIE GOHMERT, TEXAS. I was first notified in 2006 that there was a tiny little innocuous- looking plant that had been found that year on Caddo Lake. Maybe if it was a giant blob or something, they would make a movie about it and everybody would get scared, but anything that doubles in size in less than a week is something to be concerned about. Giant salvinia has been discovered in 90 different locations affecting 41 freshwater drainage basins in 12 states. It doesn’t pose the threat apparently in the north because of the cold winters that it does to freshwater bodies here in the south of our country. It was first discovered in Caddo Lake in May of 2006, and two years after that, it was discovered that this tiny, innocuous plant that started as basically nothing apparently had grown to over a thousand acres in just two years.

A single plant has been found to cover 40 square miles in three months. If left untreated, giant salvinia can completely take over and destroy the ecological system of any freshwater body.

It may live for weeks even when dry and out of the water on a boat trailer, and if it gets back in the water goes right back to reproducing and doubling in less than a week. For those who are concerned in our country with endangered species, it is important to note that 42 percent of all endangered species in our country are mainly threatened or most threatened by non-native invasive species. I have watched numerous activities on Caddo Lake to remove it mechanically. Australia has tried to eradicate it biologically, chemicals, using weevils, and also with saltwater.

Robert Adley, Louisiana state senator, district 36. Spraying has been beneficial but depends greatly on the weather for its effectiveness. Spraying requires a specific ratio of water to the sprayed chemical. After spraying, it takes time to establish and begin to kill the salvinia. If much wet weather is encountered after the spraying, the benefit of spraying is reduced due to change in ratio. The plant grows in three layers, and spraying kills only the top layer. Hence the amount of chemical needed is three times the initial amount used. Beetles in giant salvinia were transported to the lake in trucks and put it into the lake at specific points. The use of beetles has met with some success, but they’re greatly diminished during cold winters. Hence, the use of beetles is part of control, but not sufficient by themselves. It’s my understanding that beetles do a much more effective job in Brazil because they can survive the winters that are more moderate there.

The Department of Wildlife and Fisheries tried lowering the lake to allow the plants to dry out and die, but that’s been of limited effectiveness.

Gary M. Hanson, Director, Red River Watershed Management Institute, Louisiana State University Shreveport. I have served as a member of the Louisiana Hypoxia Subcommittee for a number of years.

This group has been tasked with evaluating the massive low oxygen or dead zone that occurs off the coasts of Louisiana, Texas and Mississippi each summer. The dead zone has been increasing over time and is considered a serious threat to our gulf fisheries. Early predictions for this year indicate that the dead zone will cover a record area of over 24,000 km2 or 9300 square miles. The excessive nutrients flowing from Mississippi River tributaries into the Gulf of Mexico each summer is the cause of this worsening situation. This year’s record floods will be a major contributing factor if the anticipated record dead zone forms. The nutrients stimulate excessive plant (phytoplankton) growth, which eventually die and as their biomass is oxidized most of the dissolve oxygen is removed from the water column.

Most experts agree that one key factor that is responsible for Giant Salvinia inundating and taking over fresh water aquatic habitats is the increase in nutrient levels in targeted water bodies (urban and agricultural runoff, leaking septic systems and land disturbance).

The COS has been working diligently to control Giant Salvinia and Hydrilla in Cross Lake, the only source of water for Shreveport and Barksdale Air Force Base. Already this year these plants have advanced to growth stages that are equivalent to late July or August because of the drought and unseasonably high temperatures.

The Lake Bistineau Task Force has also been working relentlessly to control the Giant Salvinia. The Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries have been trying a spectrum of approaches that includes, introducing Salvinia weevils, spraying large amounts of herbicides, removing cypress trees and draining the lake. The Task Force is considering modifying the dam so that the Giant Salvinia can be floated out of the lake into Loggy Bayou and ultimately the Red River.

There have been some short-term successes. The Task Force has spent about $2 million to date with $400,000 spent for herbicides in one year. Draining the lake leaves massive deposits of nutrient laden biomass on the lake bottom. As the lake is refilled this decomposing biomass provides a ready source of nutrients to perpetuate the growth of more plants. These various strategies and methods that are intended to manage and control Giant Salvinia all have drawbacks and disadvantages. It appears no one knows what affect the massive amounts of herbicides will have on the wildlife and fish, much less humans that consume them, In some cases, the strategies and methods already used may be considered to be as detrimental (or more so) as that of leaving the plants in place.

The draining of the lake should be a desperate last resort which is devastating to the lakes’ ecosystem and only provides temporary control of the spread of the plants. Therefore, the only solution is to use a coordinated holistic approach to physically harvest and remove the biomass in a cost effective manner and thereby limit herbicide spraying to only those areas that are not accessible to current and future harvesting methods.

I am convinced that the only strategy going forward that will work is to cut through the jurisdictional red tape that causes time delays and increases the expense to fight the menace, by bringing in the private sector to work through joint public-private ventures to first, harvest and transport the biomass and then second, find alternative uses for it as biofuel and/or soil amendment, etc. Transportation will be the key cost factor in the future that will affect all aspects of the strategy and methods to harvest and remove the biomass from the water and then move it to commercial users and areas that may use the biomass cost effectively.

The Salvinia could be moved over the top of the existing dam in high water conditions. Hence, much of the Salvinia was removed from the lake last year by flowing Salvinia over the top of the darn. However, in normal weather that will not work because the actual control of water levels is at the bottom of the dam

Additionally, the Wildlife and Fisheries expressed the need to remove some of the trees in the lake that are retarding the movement of the plant towards the channel and retarding the ability to spray more efficiently. To my knowledge, no trees have yet to be removed for various reasons.

When the Salvinia flows from the lake over the dam, it eventually makes its way into the Red River. As long as the Salvinia is flowing within the Red River, it will not establish itself. However, oxbows in the river are at risk. Hence, I withdrew the amendment to fund the restructuring of the dam until the matter can be resolved. As of now, Wildlife and Fisheries tells me they are allowing the lake to fill again and will continue with spraying. Additionally, it is my understanding that they are evaluating so-called skimming methods for the removal of Salvinia.

HENRY L. BURNS, LOUISIANA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. Lake Bistineau has had a torrid history with invasive plants going back to the 1940s. Some of the types were water hyacinths, alligatorweed, hydrilla, water primrose, and now the giant. Salivinia can double in 3 to 14 days depending on conditions. Lake Bistineau is the perfect nursery. This shallow, nutrient-rich inland water body spanning over 17,000 acres with over a million acres of watershed that feeds it from rich agricultural land, towns and cities, and industries discharging [waste] water. Half of Lake Bistineau is forested with cypress trees, providing a perfect nursery. What type of impact do we have, whether it’s economic, there’s recreational, hunting, fishing, water sports has been at best the last few years hit and miss. Congressman Fleming, it is the number one complaint that we get. In fact, it’s kind of dangerous sometimes to go to ball games because people’s hunting spot or fishing spot has been hit. And then, of course, there’s property values and broken dreams from people who have bought homes along these scenic river areas wanting to make their retirement there, to a place to bring their grandchildren out to fish.

The biggest question, the number one question I’m asked is when are we going to get our lake back? There are numerous unintended consequences that has taken place, and let me just share a couple of those with you. One, my son’s in-laws live on Lake Bistineau. They went out to have a day of fun and recreation. The motor clogged with all this invasive plant and it burned up the motor, so they struggled to get the boat back to the shoreline. Well, he thought he was in three or four feet of water because with the canopy there, you couldn’t really tell. He jumps out of the back of the boat to push it to the shore, breaks his leg. Now, that’s just from one family’s point of view. A story that’s even more outlining on what unintended consequences, and, Congressman Fleming, you have Shawn that works for you. Her sister Dotie Horton and Gary were out fishing on Bistineau. Their boat got hung up in a lot of aquatic invasive plant material, and he tried to push it in. When they pushed the boat, it finally jettisoned and clipped Dotie on the head, just barely, and Gary pulled his back muscle, so all the attention was given to her husband. Two days later, we were at LSU Medical Center and having lifesaving surgery because of the contusion and the hematoma that was caused from just that slide.

HON. ROBERT BARHAM, SECRETARY, LOUISIANA DEPARTMENT OF WILDLIFE AND FISHERIES.

We have two congressmen representing two states here. It won’t be long and you’re going to have a whole panel of congressmen that’s going to include Mississippi, Alabama, and certainly Florida. It’s going to happen to us. I wish I could tell you we’re winning this battle. We’re not winning the battle. My budget is just under $8 million.

On the leaves, it’s got these little fibrous hair that protect it from chemical spray, and we just can’t get to it.

One of the effective tools we have is Galleon. It’s a saturation complex that must remain in the water column from 60 to 90 days. Now, we’re in a drought now and it will work in a drought, but if you get a rain event, it dilutes it and it doesn’t work, and Galleon cost over $1,850 a gallon, so you can see with my budget, I don’t have the money to use Galleon everywhere, and it’s not the silver bullet. I could go on and on, but this is a horrific problem, and all the help you can give us, we need it.

The green monster, as some call this plant, works 24 hours a day, seven days a week. In as few as three days, it is capable of doubling its biomass. And in as little as seven days, giant salvinia can double surface coverage of water bodies. It spreads incredibly quickly, devouring the resources and damaging the habitats within water bodies across our state. There is no easy answer to this dilemma. We can’t simply spray every area to kill it. We can only introduce a predator and hope for the best. We can’t fence it off or deploy booms and wait till the winter comes to kill it off. And no matter what efforts we take to prevent the spread, all it takes is one alligator, one nutria or other wildlife, to move from an infested water body into an area where giant salvinia hasn’t yet taken root, and the spread continues.

While this rootless aquatic fern flourishes during the summer months, it is incredibly hardy. Stress, lack of water and cold winters won’t necessarily kill off the plant. And in water bodies like the Barataria and Terrebonne basins, the temperature doesn’t drop nearly enough to produce a large scale kill-off of the plant.

Giant salvinia even comes armed with its own defense mechanism in the tiny, white hairs that capture herbicides just above the plant’s surface, seriously challenging the efficacy of any spray treatment.

For this year through May 31, the Department has utilized 21 spray crews and contractor air boat treatments to control 10,730 acres of giant salvinia. These herbicides provide us with the ability to kill off the plant during the spring and into the warm summer months when it would flourish. However, spraying can be incredibly difficult. Many areas, such as Lake Bistaneau, are also inhabited by the iconic cypress tree. The close proximity of trees can make it incredibly difficult for spray crews and their boats to access parts of these infested water bodies. And as the tree loses its leaves each year, that debris further fuels the degradation of the aquatic habitat. While we advocate for moderate tree removal, this is both expensive and, at times, unpopular with the public.

Spraying is also an incredibly expensive treatment method. For each gallon of Galleon, the herbicide our Department utilizes, it costs us $1,851 per gallon. With more than 25,000 acres infested, simply spraying would be an incredibly expensive and likely ineffective task. And the costs not included in the cost per gallon for herbicide are the manpower costs to the state, the cost of the equipment, the boats and the fuel.

Shallow cypress tree stands have provided refuge for the giant salvinia. Biologists and spray crews are unable to access the plants in shallow areas.

Because this rootless plant can completely cover the surface of water bodies, it severely limits public access for boating and fishing. It can be burden for property owners with waterfront access and it can be unsightly for residents who are used to enjoying the simple pleasure of viewing an uninfested lake.

While we don’t expect the actions of residents and those tourists who enjoy the lakes and rivers across Louisiana to be able to wholly prevent the spread of giant salvinia—a 10 inch rain event can do more damage in a short amount of time.

Let me be clear, giant salvinia cannot simply be eradicated. This deft plant is far too integrated into our environment to kill off. This will be an ongoing issue that will require local, state and federal dedication of funds to battle.

Michael J. Grodowitz, Ph.D., Research Entomologist, Engineer Research and Development Center, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Vicksburg, Mississippi.

Giant salvinia ( Salvinia molesta), a native of Brazil, is a floating fern introduced into the United States through the aquatic nursery trade. Since its introduction in the middle to late 1990’s, giant salvinia has dispersed naturally and by humans, and in less than 20 years can now be found as far west as the Hawaiian Islands, east into the peninsula of Florida, and north into Virginia. It is one of the world’s worst weeds and is causing manifold problems throughout the sub-tropical and tropical regions of the earth. Impacts are varied and include hindering navigation; disrupting water intake for municipal, agricultural and industrial purposes; degrading water quality; decreasing floral and faunal diversity;

It impacts threatened and endangered species; and increasing mosquito breeding habitat for species that are known to transmit encephalitis, dengue fever, malaria, and rural filariasis or elephantiasis.

Giant salvinia causes significant problems in over 20 other countries including Australia, New Zealand, Fiji, the Philippines, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Papua, New Guinea, the Ivory Republic, Ghana, Zambia, Kenya, Namibia, Botswana, South Africa, Madagascar, Columbia, Guyana, and several Caribbean countries (including Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Trinidad). This list increases yearly. In the United States, it is now found in at least 90 localities and is especially troublesome in southern states including Texas, North and South Carolina, Louisiana, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi and west into Arizona, and California.

Giant salvinia reaches damaging infestation levels because of its tremendous growth rate. While it has been shown to only reproduce vegetatively (i.e., viable spores are not produced) this is more than enough to allow it to form surface mats up to 1 meter thick with plant numbers approaching 5000/m2 and biomass production of upwards of 100 tons/ha/year. Even greater production is possible under more favorable conditions. It has been known to double in number in one to eight days, depending on environmental conditions.

Numerous control strategies have been implemented for the management of salvinia. These include the use of traditional methods such as mechanical control (i.e. cutting or plant removal) and chemical applications. Mechanical control options are not particularly effective. They are expensive and often do not produce results needed for even partial management.

The use of chemical technologies can be effective but tend to produce only short-term control and can become expensive, especially when multiple treatments are needed over the course of a growing season. The use of alternative control methods such as biological control is highly promising and has been shown to produce long-term sustainable control. One agent has been approved for release in the United States, the salvinia weevil (Cyrtobagous salviniae), and is the method of choice for management in many overseas locations. While effective, biological control can take several years and there is some concern that it may not be particularly effective in the more northern extreme of salvinia’s distribution.

Other methods employed for salvinia control in the United States include flushing and drawdowns. Increasing water flow to ‘flush’ plants out of a waterbody or drainage can reduce biomass locally but may increase the distribution of salvinia downstream. Drawdowns (which serve to desiccate and kill the plant) do reduce biomass and can isolate the plant into smaller areas allowing easier access for mechanical removal or chemical treatment. However, when water levels increase remaining plants can be scattered throughout the water body making treatment even more difficult.

Currently, chemical control is the most widely used management strategy in the United States for the control of salvinia. A wide variety of products are employed mainly those containing diquat, glyphosate, and to a lesser extent fluridone and carfentrazone-ethyl. Active ingredients recently labeled for aquatic use including penoxsulam and flumioxazin, have been evaluated and are effective but have yet to be used on a wide scale. As indicated earlier, chemical applications can be highly effective, producing dramatic control 90%, in a manner of days or months. However, several factors often dictate the need for repeat applications and diligent post- treatment monitoring. One important factor is the rapid growth rate of salvinia which allows the plant to easily outpace the current application of chemicals.

Probably a more important factor is the ability of salvinia to re-grow from small buds or plants that are missed during chemical application, especially in backwater coves where overhanging vegetation can hide small plant populations or where plant growth is dense and underlying layers are protected from surface sprayed herbicides. These plant fragments can be smaller than 1/4 inch.

In addition, the plant can easily be transported by a variety of human mediated means. Thus, water bodies where salvinia has been eradicated can be easily re-infested. Therefore, the rapid growth rate of salvinia and its excellent dispersal ability necessitates the use of greater amounts of chemicals with increased labor costs for application which leads to a never- ending cycle of chemical use.

It is important to understand and address underlying causative factors allowing the formation of damaging infestations of giant salvinia. One of the more important causative factors is high nutrient levels that allow for increased and explosive plant growth. While it is difficult to minimize nutrient influx into water bodies, several strategies have been used with varying success. These include repairing leaking septic systems or positioning the septic fields away from the water body, implementation of regulations prohibiting fertilization of lawns right up to the water’s edge, and ensuring that sewage treatment plants use tertiary treatment processes to limit nitrogen and phosphorus loading. One potential method is the use of re- vegetation techniques to establish a diverse community of non-invasive native vegetation that will act as nutrient sinks to reduce nitrogen levels thereby limiting plant growth and reducing the chance of new infestations by salvinia as well as other invasive species including water hyacinth, hydrilla, and Eurasian watermilfoil, among others.

Randy Westbrooks, Invasive Species Prevention Specialist, U.S. Geological Survey, U.S. Department of the Interior.

Giant salvinia is a small, free-floating aquatic fern that is native to southeastern Brazil and northeastern Argentina. It is somewhat similar in appearance to our native duckweed (Lemna minor), but bigger. Its most notable feature is the rows of ‘‘hairs’’ with 4 branches that join in a cage-like tip. The tip traps air that helps the plant float on the water surface. Giant salvinia prefers tropical, sub-tropical, or warm temperatures and grows best in nutrient-rich, slow-moving waters such as ditches, canals, ponds, and lakes. It is a freshwater plant but can tolerate salinity levels in estuaries up to levels of about 10% that of seawater.

It is no exaggeration to say that Giant salvinia is one of the world’s worst weeds. It takes only a fragment of a single plant to multiply vegetatively and produce a thick floating mat of plants on the surface of standing water. The mats clog waterways and block sunlight from reaching other aquatic plants below the surface, reducing the amount of oxygen in the water. As these plants die and sink to the bottom, decomposer organisms use up even more oxygen in the water. The mats also impede the natural exchange of gases between the water and the atmosphere, which can lead to stagnation of the water body. Ultimately, these processes will kill all plants, aquatic insects, and fish living below the mats. The mats also provide ideal conditions for mosquitoes to breed, block access to boat docks and boat ramps, and interfere with navigation.

Despite the success of using weevils to control Giant salvinia in some regions, the Salvinia weevil is not a fully effective control method in every case because it is less tolerant of cold temperatures than Giant salvinia. For this reason, the Salvinia weevil was unsuccessful controlling Giant salvinia in Kakadu National Park in the Northern Territory of Australia.

SALVINIA CAN’T BE USED FOR BIOFUELS

Dr. GRODOWITZ. Salvinia is 95% water. The economics of harvest are poor – you’re moving a lot of weight just from the water. So biofuel production, salvinia is not a very good candidate. And other aquatic plants that have been attempted to use for biofuels haven’t worked. You have to be careful when you try to promote the use of an invasive species because how are people going to use it and if you spread it around you’re going to have problems with it again. So I would rather see some kind of native plant that’s not as invasive as salvinia used for biofuels.

Dr. WESTBROOKS. The idea of getting it back to the land was an issue to begin with in Caddo Lake is when you have mechanical harvesters, they have a huge mass of this plant, how do you get it back to the land. So transportation of it back out to some place where you could actually go process it, unless you could process it there on the lake, if you had a processor on the lake where you’re removing the water and if you’ve just got the biomass of the cellulose left of the plant.

Dr. FLEMING. So if it’s desiccated, then obviously there’s very little fuel left then because the weight is—vast majority is water to begin with.

THE PROBLEMS WITH USING SALT WATER TO KILL SALVINIA

Dr. GRODOWITZ. We know for sure that they’re not very tolerant of saltwater. But it can handle even higher salt concentrations than recent research that was done in our Dallas facility. And putting saltwater into freshwater will create huge problems, so I’d stay away that if I could.

Mr. BARHAM. It will take too much salt to reach the level you need. Before you kill the salvinia, you’ll be killing the cypress trees and the bass and the freshwater fish.

Dr. SANDERS. If you added salt instead of saltwater, the lethal level of salt for giant salvinia is around six parts per thousand or six pounds of salt for every thousand pounds of water. Water weighs about nine pounds per gallon. So it would take 750 18-wheeler loads of salt for Caddo lake and kill all your cypress trees. Over time the water would desalinate if it is a flow-through lake and the saltwater would move downstream or dilute itself out with enough rainfall.

EVEN ICE WON’T KILL IT

Dr. WESTBROOKS. When you have a mat—it’s like insulation. I’ve seen the plant in ice in North Carolina and, of course, that would die. But if you get a mat—plants in the middle survive.

CHEMICALS HELP BUT CAN’T ERADICATE IT

Dr. GRODOWITZ. There are two really broad types of herbicides that are used for salvinia control. Some are contact herbicides. Some you spray on top of the plant. Kills the plant fairly quickly. There’s also contact herbicides that are systemic. 24D is one. It takes a little longer to kill. But what you know about Fluridone and Galleon, as you put it in the water, you have to maintain a certain concentration at a certain length of time to kill the plant, but it’s good because you’re killing plants over a larger area, but very, very expensive and hard to maintain concentrations up there. There are several new registrations, chemical registrations that have come out, penoxulam and flumioxazin, that the Corps of Engineers has been testing right now to look at their effectiveness, especially in combination with the weevils. So if you have weevils out there, you spray these herbicides, what kind of impacts on the weevils, can you maintain weevil populations, will the weevils come back afterwards.

Mr. GOHMERT. We’re dealing with freshwater, in some cases drinking water. What threats do those—whether it’s Galleon, Sonar, 24D, what do they pose to other vegetation or to the freshwater itself? Do we know of any risks.

Dr. GRODOWITZ. Any of those contact herbicides will kill any plant that gets sprayed, so you have to be very careful. Your application techniques are very important. We want to keep hydrilla and water hyacinths because they add some beauty to lakes.

Dr. WESTBROOKS. The EPA would say if there were concerns about drinking water. I think most of the water you’re talking about is in rivers and lakes and ponds and stuff like that. There wouldn’t be drinking water concerns, I guess, unless you had a well beside the lake.

SALVINIA CAN ALSO INVADE SLOW-MOVING RIVERS

Dr. GRODOWITZ. [In response to navigation problems in flowing water]. It won’t accumulate in fast flowing water, but it will in slow-moving waters. For example, the Sepik River in Papua New Guinea is huge, but very slow moving and covered with salvinia. Whole villages were moved because the people couldn’t get into the river to fish.

Dr. WESTBROOKS. In Lake Victoria near Kenya four years ago the mats would get so thick trees would grow in them, so they became floating tree islands. In spring floods these floating mats could clog the backwaters of rivers and cause problems downstream.

Dr. GRODOWITZ. If you start having flooding events with salvinia in the waters, you’re going to have more damage because you’re looking at all this huge biomass in the water being pushed further downriver and cause even more damage.

Dr. WESTBROOKS. I don’t know about salvinia, but I know Florida water hyacinths would pile up against bridges and push the bridges out, so I don’t know if it’s comparable, but it probably could.

Mr. GOHMERT. One of the problems that is a result of having all these invasive species, the water hyacinths, hydrilla, and now giant salvinia, this stuff does die and goes to the bottom. And in the old days a giant flood would sweep all that sediment out and you’d get fresh native growth again. I had one landowner say he bought his property because he liked how deep it was right there at that point in the lake, which means it’s normally more expensive property because it’s deeper, and it was 15 feet right there where he was located, and now it’s seven feet because of all the dead masses that go down and build up. I’m just curious in either Texas or Louisiana, is there any money that’s been allocated and from the Federal Government toward dredging out some of this old plant mass?

Mr. BURNS. I’m not aware of any dredging for the reason of the plants. Only dredging I’m aware of is for navigational issues. One of the problems you’ve got, I will say that you’re describing a situation that is striking fear in all of our hearts about losing bodies of water to this plant. One of the areas I’m most concerned with is the Atchafalaya Basin. It’s the largest swamp area in the country—shallow, trees, slow-moving waters.

We just opened the Morganza Spillway. Fortunately we’re not seeing a lot of salvinia at this point. Now, ultimately it’s going to get there because it’s coming out of the Red River. It’s coming down to the Atchafalaya, but that’s the place that it will take. We almost lost Henderson Lake due to water hyacinths. And so we’ve got some real threats from these types of plants in certain environments, these shallow, slow-moving, tree-strewn, nutrient-rich environments across the Deep South.

Dr. WESTBROOKS. To begin with, all we know is that it takes oxygen out of the water and is killing fish and stuff like that, but if this organic matter builds up like peat in the bottom of these lakes, you may have an entirely different problem. It’s going to change the ecological characteristics of the lake.

Dearl Sanders, Edmiston Professor and Resident Coordinator: Bob R. Jones- Idlewild Research Station, Louisiana State University Agricultural Center

With the discovery of giant salvinia near Cameron, La., in 2000, a biological control program was initiated. It is interesting to note that the only effective eradication of giant salvinia in Louisiana was accomplished at the Cameron site by using salt water. The traditional drainage and pumping facilities were temporarily reversed, and the infested canals and associated ponds were filled with high salinity water from the nearby Calcasieu Navigation Channel. After the salvinia had died, the process was reversed, removing the salt water from the system with little, if any, negative effect on the native plant life.

Studies at the Golden Ranch site confirmed reports in the literature from Australia that under ideal growing conditions giant salvinia can approach an 80 percent daily coverage rate, or, stated another way, the giant salvinia can reach a point where it can double the area of water covered every 1.5 days

In southern Louisiana it takes a minimum of two full years for the population to reach a threshold where the weevils consume the salvinia faster than the salvinia can reproduce.

An extensive grass carp biological control trial was conducted at the Golden Ranch site in 2009. The trial confirmed that grass carp will not eat giant salvinia even when it is the only plant material available. This was not unexpected, since grass carp usually do not consume floating plants and giant salvinia contains a metabolic inhibitor (thiamine inhibitor) that if consumed in quantity is toxic to the fish (and other animals).

It should be noted that the salvinia weevil never eradicates giant salvinia. As in its native Brazil, it consumes salvinia to the point it can no longer maintain huge population numbers—allowing some salvinia to survive.

The results of over more than two dozen herbicide trials conducted by the LSU AgCenter since 1999 have identified a number of herbicides that are effective in controlling giant salvinia when applied according to directions. A number of the effective herbicides have obtained federal registration from the EPA and are available for use. These herbicides can be divided into two groups:

Foliar sprays and total water treatments. Diquat (Reward), flumioxazin (Clipper) and glyphosate (numerous trade names) are foliar treatments shown to be effective with multiple applications. Fluridone (numerous trade names) and more recently penoxulam (Galleon) are total water treatment herbicides (the giant salvinia absorbs the herbicide through root uptake) often are effective from a single application, but the contact time (time the plants are exposed to the herbicide) may be as long as 60 days. Exchange of water (rainfall, normal current flow, etc.) with the minimum exposure time negates control.

Even with these herbicides proven to be effective, chemical control of giant salvinia is problematic for several reasons:

- All of the foliar applied herbicides require multiple applications to have a significant effect on matted giant salvinia. Multiple applications are expensive and labor intensive.

- The total water treatment herbicides require long contact times. This works well in small confined areas (ponds with little watershed area), but it often does not work well in larger water bodies with larger watersheds and does not work at all in areas of moving water.

- All of these herbicides are expensive (as high as $1,600 per gallon on the upper end), and state budgets are limited.

- With the phenomenal growth rate of giant salvinia (Attachment 1), complete control is difficult to achieve, since only a few surviving plants can repopulate and area in a brief time.

The foliar materials that are out there are effective, but it’s like peeling an onion. You just have to peel off layer after layer after layer after layer. It’s expensive and requires a lot of tenacity to go out and spray the same body of water every two weeks for the rest of your life.

The total water volume treatments that were mentioned, like Galleon, is very expensive, just 500 gallons costs a million dollars, and if you apply it betting it won’t rain for 35 days – that’s a hard bet to make.

Salvinia weevils are about the only weevil that doesn’t fly, so someone to hand move them to nearby bodies of water, which is very labor intensive.

Basically our hope now is to continue with the weevil releases in south Louisiana. We continue to screen herbicides. We’re doing all these other tests that really haven’t amounted to a whole lot. We’ll continue to do it hoping

MICHAEL MASSIMI, Invasive Species Coordinator, Barataria-Terrebonne National Estuary program

This area is about four million acres between the Mississippi River and the Atchafalaya, roughly triangular, down on the coast, coastal estuaries. We very much appreciate the weevils down there.

It’s an area that has a lot of environmental problems. We’re the fastest disappearing land mass. Everybody knows about Louisiana’s trouble with land loss. The invasive species is no less an issue down there. We have plenty of them.

Since I’ve been there for seven years, we have six new invasive species recorded in the Barataria-Terrebonne. Plenty of salvinia in the coastal estuaries. It’s not just up here in the northern part of the state. After Hurricane Katrina, we started finding giant salvinia in several new locations. The hurricane definitely spread it around, and my fear is that this river flood of 2011 is going to really spread it a lot farther, into the Atchafalaya basin and then, of course, into the Barataria-Terrebonne system as well. It’s found in the Barataria system, the north rim of Barataria Bay, including in Jean Lafitte National Historical Park, and I believe that we’re going to see severe impacts very soon in the Penchant Basin system of Terrebonne. That is where all the Atchafalaya River water eventually went.

The impacts are very severe. Total shade, blocking gas exchange on the surface, no oxygen getting through. As the plant decays, that sucks oxygen out as well, and causes fish kills. We’re seeing that in the southern part of the state.

The mat is so thick that even your air-breathing animals, even big ones like otters, don’t want to go through that. Ducks will relish our native duckweed, which is a similar floating plant, but it’s a thin mat, and ducks can get through it. Ducks will completely avoid a water body covered with giant salvinia.

Water management structures get overwhelmed. Boating is impossible, even sometimes for larger vessels. A mat three feet thick is going to impede a pretty big boat.

Intakes for industrial water or municipal drinking water get clogged. Cross Lake now has giant salvinia in it, and that’s where the City of Shreveport gets their water from.

And speaking just generally about invasive species biology, invasives love to stir up habitats. They have a much harder time invading an area if every niche is filled with a native species and it’s a functioning healthy ecosystem. You do something to disturb that, the invasives come in. They’re great generalists and they’re great pioneers of disturbed habitats. Using chemicals repeatedly knocks back not just your target species, it knocks back a lot of species. You’re degrading the habitat in that way, and so it can be a negative feedback or positive feedback, rather, where a further degraded habitat is now primed for further invasion. And we see this with invasive species helping one another. An invasive actually degrades a habitat, clearing the way for another invasive to come in. Common in invasion biology. So one thing we can do that hasn’t been mentioned is good restoration and restore native vegetation, cut back on the nutrients. That’s going to be part of a comprehensive plan as well.

I’d like to just say that in invasive species management, we’re constantly caught in a reactionary mode, so we’re here today to talk about giant salvinia, but we really should take a much more high altitude view and much more widespread and talk about invasives in particular pro-action rather than reaction. There is a nutria bill. There is a feral hog bill, and maybe there will be some salvinia action at some point, but if we can have stricter regulations on what gets imported into this country to begin with, we might avoid the next giant salvinia.

The invasive floating fern giant salvinia (Salvinia molesta) is possibly the most noxious of all aquatic weeds.

Introduced and spread mainly as an ornamental by the horticulture and pond garden trade, it has become established in tropical and subtropical regions on four continents.

In the US, giant salvinia is established in at least 11 states has the potential to devastate freshwater habitats in as many as 20 states.

Giant salvinia is currently considered established in at least 15 parishes, mostly in the southeast and northwest of the state, and the river flooding of 2011 will most certainly result in additional introductions. Giant salvinia can thrive in any freshwater area of the state, and I believe that we are, unfortunately, only on the leading edge of the giant salvinia invasion. The growth rate of giant salvinia is exponential. It doubles its coverage area in as little as a week under good growing conditions. A single plant could cover 40 square miles in three months. Waters infested with giant salvinia quickly become covered by a thick mat of vegetation. The mat can be up to three feet thick at the surface, making navigation impossible, even for relatively large boats. The mat is also much denser than other floating plants, blocking sunlight almost completely and greatly inhibiting oxygen exchange at the surface. The decay of plant masses further deoxygenates the water. The result is catastrophe for native flora and fauna. Hypoxic waters can cause fish kills. Submersed native aquatic plants are shaded out and they die. Habitat is destroyed for air-breathing animals like otters, diving birds, turtles and frogs, which cannot penetrate the mat. Ducks, which relish surfaces covered with the much thinner native duckweed, will completely avoid surfaces covered with salvinia.

There is also evidence that prolonged presence of salvinia mats causes gradual acidification of lakes and ponds.

Giant salvinia infestations have severe human impacts too. Water management structures are damaged or rendered useless, boating and commercial navigation is impeded, intakes for municipal drinking water or industrial facilities are clogged, and recreational uses such as fishing, waterfowl hunting, paddling, or swimming are stopped.

Harvesting salvinia mechanically can be effective only in very small infestations; otherwise the sheer weight and volume of the wet plants are unmanageable. Booms and other structures to prevent the movement of salvinia can protect small areas, but often get overwhelmed by the massive mats when pushed by wind or current.

KEN WARD, PROJECT MANAGER, DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS, CADDO PARISH

1,700,000 gallons of water every day are used to provide quality drinking water to Caddo Parish residents. But Giant salvinia reduces the oxygen in the water, increasing treatment requirements.

Manpower for spraying is also very limited. Spraying cannot be applied in the rain or high wind conditions. Boat launch barriers have been installed at Caddo Parish’s Earl Williamson Park in Oil City to help assist giant salvinia from entering the boat launch areas. This helps keep the plant from attaching to boat trailers during launch and release, but during high winds, giant salvinia can be blown in the barriers, which mean—which cause problems in the launching areas. Caddo Parish has passed and posted ordinances on the prohibition of transportation and spreading of giant salvinia. Enforcement of such ordinances are very expensive and time consuming.

Caddo Lake is one of only 27 wetlands in the United States recognized by the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands. The bald cypress forests of Caddo Lake, including trees as old as 400 years, host one of the highest breeding populations of wood ducks as well as prothonotary warblers and other neotropical birds. The forests and wetlands of Caddo Lake are critical for migratory bird species within the Central Flyway, including tens of thousands of migrating waterfowl that utilize Caddo Lake (and other nearby lakes) as resting and feeding grounds. However, these internationally-recognized wetlands are threatened by Giant Salvinia, one of the world’s most noxious aquatic weeds introduced from Brazil as part of the pet industry. Giant Salvinia grows rapidly and spreads across water surfaces, forming dense floating mats that reduce light penetration and result in oxygen depletion of the lake. This prevents growth of natural vegetation, a food source for waterfowl, and the mats of Giant Salvinia also eliminate open water on lake for waterfowl to use for resting purposes.

Invasive species like Giant Salvinia are one of the greatest threats to fish, wildlife, and plant biodiversity facing the United States and disrupt the economy and ecology of our nation. Invasive plants threaten private working lands and publicly protected lands and infest over 100 million acres in the United States. On public and private lands and waters of this country, invasive species negatively impact the natural systems on which we all depend and economic losses are estimated at over $100 billion annually.

DAMON E. WAITT, SENIOR DIRECTOR AND BOTANIST, LADY BIRD JOHNSON WILDFLOWER CENTER, UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN.

I’ll add to the bulleted list of problems with invasive species, that they reduce habitat for endangered species and also to the cost of $137 billion annually, they’re also the second greatest threat to native biodiversity, second only to habitat destruction.

My experience with Caddo Lake came later in life and was primarily secondhand from a woman who grew up in Karnack, Texas. With her mother dead, her much older brothers gone, and her father running the local general store, there was little time for five-year old Claudia Alta Taylor. As a child, Claudia found solace in nature paddling the dark bayous of Caddo Lake. The sense of place that came from being close to the land never left her. She would devote much of her life to preserving it. It helped define her and started her down a path that led to the White House, Highway Beautification, and the National Wildflower Research Center. That young girl was, of course, Lady Bird Johnson. And when I talked to her about invasive species when she was still alive, she said to me, ‘‘Damon, those are plants that have no socially redeeming value.’’ One of Lady Bird’s most famous quotes goes, ‘‘The environment is where we all meet; where we all have a mutual interest; it is the one thing all of us share. It is not only a mirror of ourselves, but a focusing lens on what we can become.’’

Dr. SANDERS. After 130 days, the grass carp that had only giant salvinia to eat had—a number of them died, and all of them had lost weight from the time we put them in there. Basically it boils down to two things; one, they don’t like floating plants to start with and, two, something that hasn’t been addressed here is that the giant salvinia contains a metabolic toxin, contains a thiamine inhibitor. The grass carp nibbled on it until they got sick and decided that they would eat mud after that and then die, which is what they did. We cut the stomachs open and simply full of mud. I’ve gotten requests for why can’t we use this for animal feed, cow feed. Same situation. You have to overcome this thiamine inhibitor problem to keep the cows from getting sick, so it works the same with fish.

Mr. LOWERRE. In the Caddo Lake watershed we are working with some Federal and state money on a watershed protection plan to get agricultural producers to use better management practices to reduce the extra nutrients that come into the system, since the run off of phosphorus and nitrogen fertilizers helps giant salvinia to grow.

Dr. SANDERS. Weevils actually swim out of the pond trying to seek another batch of salvinia somewhere, and in south Louisiana, they’re all consumed by fire ants, another invasive species—and none of the weevils made it more than about 20 feet from the pond

CYPRESS VALLEY NAVIGATION DISTRICT MARSHALL TEXAS 75661 GIANT SALVINIA RESPONSE PROGRAM PRESENTED TO THE RED RIVER VALLEY ASSOCIATION IN TEXARKANA, JUNE 1st, 2011

Caddo Lake has long had a problem with invasive species. . .namely Water Hyacinth. Some say this problem dates back to the Late 1950’s when Lake of The Pines was impounded. Other invasive species are also present in Caddo, some cause little problem and some are or have the potential to be major problems. The worst offenders include; Giant Salvinia, Hydrilla, and Alligator Weed. Others that tend to be more localized are: Water Millfoil, FanWort, Water Primrose, Elodea Parrot, Feather Pennywort, Frog’s Bit, Spatterdock Duck weed, and Watermeal . All types of lilies like Egieria Coontail and American Lotus. There are three main control regimes for invasive species: Bio Controls, Herbicide Application, and Containment/Removal of material. The Containment/Removal of Giant Salvinia has been tried on Caddo in recent years. A trial using a barge with a conveyor system was used to remove and transport the material to shore was conducted. The trial was successful in that it removed the material from the shallow stumpy environment without breakdowns, however, the overall process was slow and not cost effective for large areas.

CVND’s efforts on Giant Salvinia started in 2007 when Giant Salvinia was first reported in the Jeems Bayou area of Caddo Lake. A plan was devised to put up a barricade 2 miles long across the middle of the lake to intercept the floating salvinia. The fence was erected and patrolled daily. It was effective on stopping large quantities of salvinia but could not stop it all. The fence was destroyed by winds from Hurricane Ike and was subsequently removed from the lake.

ROSS MELINCHUK, DEPUTY EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE DEPARTMENT. For the last ten years, the Department’s annual statewide budget for management of invasive aquatic plants has ranged from several hundred thousand dollars to 1.5 million. A comprehensive plant management program would require in our estimation about $2 million annually to implement, at least $600,000 of which would be targeted at giant salvinia.

Targeted outreach programs can be effective, but they, too, are expensive. The Department spent about $275,000 in 2010 for a one-month media campaign focused on Caddo, Lake Conroe, Toledo Bend, and Sam Rayburn reservoirs. The campaign included radio, television, print ads, online advertising, billboards, ramp buoys, pump station toppers, pretty comprehensive campaign. The boater survey conducted following the campaign showed us that 51% of boat owners had seen advertising or information about giant salvinia and that awareness had increased. Key point, in fact, 96% of boaters surveyed reported that the campaign made them more likely to clean their boat and trailer in the future.

Texas A&M College of Agriculture and Life Sciences submitted for the record:

- Establish, operate and maintain a salvinia weevil rearing facility near Caddo Lake to serve as a ready source of weevils for release on Caddo Lake and also provide a living laboratory and nursery to develop a better knowledge of salvinia weevils and their behavior. So far about 75,000 adult weevils have been released on Caddo Lake into 4 isolated areas from the rearing facility and 250,000 weevil larvae. Larvae are the primary killer of giant salvinia as they bore their way out of the plant after hatching from eggs laid by adult weevils in the stems of the plant, thus seriously damaging the Salvinia

- Currently in the process of hiring a private applicator to chemically treat giant salvinia on Caddo Lake in 2011 to support and complement other spraying efforts

Mr. GOHMERT. You’ve talked about 1.3 million weevils costing $35,000 and how you mechanically can move them and all. Who counts those things?

Dr. SANDERS. Another one of these myriad studies, how many weevils are in a pound of salvinia and the first question we tried to answer. There’s actually entomologists came up with a system decades ago that they run a series of plant matter through, it’s called a berlese funnel. What it is is a—just like the name sounds, it’s a funnel with a screen in it. You put a heat source over the top, in this case a fluorescent light bulb, and the heat and the light forces the live insects down through the plant mass, through the neck of the funnel, down the funnel into some type of collection device. We use little plastic bags. But after the plant matter is completely dry, we pull them out, we pour them out, we count the numbers of weevils that are in there. We put a kilo of stuff in, we count however many weevils are at the bottom, and that’s how we make the determination, and we make hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of these determinations.

3 Responses to An invasive green monster that can double in 2 days and impossible to control threatens 20 states