Preface. This is the sixth of nine posts about this very important book on how and why a large percent of Americans have has been irrational for 500 years.

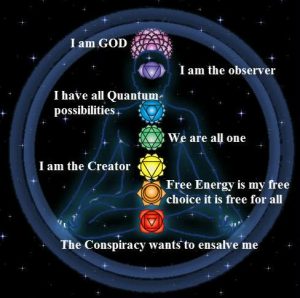

New Age and supernatural beliefs are the religion of people who can’t swallow Biblical or any other mythology.

Links to the 9 parts of this book review: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Alice Friedemann www.energyskeptic.com author of “When Trucks Stop Running: Energy and the Future of Transportation”, 2015, Springer and “Crunch! Whole Grain Artisan Chips and Crackers”. Podcasts: Derrick Jensen, Practical Prepping, KunstlerCast 253, KunstlerCast278, Peak Prosperity , XX2 report ]

***

Kurt Andersen. 2017. Fantasyland. How America Went Haywire. A 500-Year History. Random House.

The New Age, alternative medicine, and other Supernatural beliefs

At the end of the 1700s, with the Enlightenment triumphant, science ascendant, and tolerance required, craziness was newly free to show itself. “Alchemy, astrology…occult Freemasonry, magnetic healing, prophetic visions, the conjuring of spirits, usually thought sidelined by natural scientists a hundred years earlier,” all revived, the Oxford historian Keith Thomas explains, their promoters and followers “implicitly following Kant’s injunction to think for themselves. It was only in an atmosphere of enlightened tolerance that such unorthodox cults could have been openly practiced.

Kant himself saw the conundrum the Enlightenment faced. “Human reason,” he wrote in The Critique of Pure Reason, “has this peculiar fate, that in one species of its knowledge”—the spiritual, the existential, the meaning of life—“it is burdened by questions which…it is not able to ignore, but which…it is also not able to answer.” Americans had the peculiar fate of believing they could and must answer those religious questions the same way mathematicians and historians and natural philosophers answered theirs.

As modern science begat modern technology, the proof was irrefutably in the pudding: we got telegraphy, high-speed printing presses, railroads, steamships, vaccination, anesthesia, more. We were rational and practical. We were modern.

Snake Oil, Homeopathy, and alternative medicine charlatans

During the First Great Delirium, the marvels of science and technology didn’t just reinforce supernatural belief by analogy or as omens—they inspired sham science and sham marvels. Especially when it came to medicine. Many nostrums were the products of knowing charlatans, but many of the most successful inventors and promoters were undoubtedly sincere believers.

If the patients also had faith in the miraculous treatments, they could even seem to work. The term placebo had just come into use as a medical term.

America had hundreds of water-cure facilities, for instance. But then we lost faith in hydropathy and stopped wrapping people in sheets drenched in cold water in order to cure rheumatoid arthritis, heart and kidney and liver disorders, smallpox, gonorrhea, and dysentery. Yet from this nineteenth-century miasma emerged one school of quackery that became huge in America and never faded away. Homeopathy was the original “alternative medicine.

Of course, swallowing arsenic or other poisons could harm patients, but homeopathy had that figured out. The medicines were made by diluting the ingredients in water or alcohol, shaking the mixture (that is, “potentizing” and “dynamizing” their “immaterial and spiritual powers”), then diluting it again, shaking, diluting some more, on and on. The dilution ratios were (and are still today) so extreme—billions and trillions to one—that the finished elixirs are just water or alcohol, containing essentially none of the named ingredient. A typical recommended dilution is literally equivalent to a pinch of salt tossed into the Atlantic Ocean.

Homeopathy, its fake medicines prescribed to cure every disease, is a product of magical thinking in the extreme.

Such pseudoscientific practices harmed healthy people no more frequently than they cured sick people, but their popularity derived from and fed the big American idea that opinions and feelings are the same as facts.

Out of this cross-fertilization of pseudoscience and spirituality came new sects and eventually one whole new American religion. In the 1830s in Maine, a clockmaker and inventor with the irresistible name Phineas P. Quimby found out about mesmerism. He became a practitioner, hypnotizing sick and unhappy people and persuading them to feel better. Quimby’s work and philosophy were a wellspring of the New Thought movement, a nineteenth-century American precursor to both Scientology and the New Age movement of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. New Thought believers figured that belief conquers all, that misery and bliss are all in your head. Some disciples were specifically Christian, some weren’t, but they all pitched themselves as scientific as well as mystical, providers of practical tools for individual perfection.

An individual mesmerist or phrenologist or hydropathist could make a decent living, but selling professional services was not really scalable as a national business. Inventing a religion, as Mary Baker Eddy did, was one way to scale. Manufacturing and selling miraculous products was another, as American wheeler-dealers figured out in the 1830s and ’40s, when branded miracle cures became an industry. Small and large businesses started selling all sorts of elixirs, tonics, salves, oils, powders, and pills. The principal ingredient of many so-called patent medicines was sugar or alcohol; some contained opium or cocaine.

One typical small-time nineteenth-century medicine-seller was a man from upstate New York who traveled the country selling nostrums. “Dr. William A. Rockefeller, the Celebrated Cancer Specialist,” his sign announced. “Here for One Day Only. All cases of cancer cured unless too far gone and then can be greatly benefited.” (His sons John D. and William Jr. became businessmen of a different kind, founding the Standard Oil Company.)

Another of the elder Rockefeller’s medicines, dried berries picked from a bush in his mother’s yard, was prescribed to women; the berries’ important contraindication—not to be taken during pregnancy—appears to be a perfect con man’s way to market fake abortifacients.

Rockefeller was a typical small-time grifter. On the other hand, Microbe Killer, a mass-marketed pink elixir, which came in large jugs and consisted almost entirely of water, sounded plausibly scientific, the way mesmerism and phrenology and homeopathy had science-y backstories: germ theory was new science, and microbe a new coinage. Microbe Killer’s claims were extreme, simple, ridiculous: “Cures All Diseases.” The inventor built Microbe Killer factories around the world and became rich.

Benjamin Brandreth got even richer. At 25, as soon as he’d inherited his English family’s patent medicine business, he moved it and his family—of course—to America. Brandreth’s Vegetable Universal Pills were supposed to eliminate “blood impurities” and were advertised as a cure for practically everything: colds, coughs, fevers, flu, pleurisy, “and especially sudden attacks of severe sickness, often resulting in death.” One ad describes “a young lady” who’d been ill for years, “her beauty departed,” but after two weeks of swallowing Brandreth’s Pills, “her health and good looks recovered.” Brandreth advertised extensively and constantly in America’s new cheap newspapers. A few years after his arrival, a contemporary wrote that “Dr. Brandreth figures larger in the scale of quackery, and hoists a more presuming flag, than all the rest of the fraternity combined.” A decade later Brandreth was elected to the New York Senate, founded a bank, and had his pills mentioned in Moby-Dick.

In 1838 a prominent physician and public health innovator published Humbugs of New York. He understood that in America, criticism and debunking were unfortunately fuel for the madness. “Persecution only serves to propagate new theories, whether of philosophy or religion,” he wrote. “Indeed, some of the popular follies of the times are indebted only to the real or alleged persecutions they have suffered…even for their present existence.

The author of another book of the era, Quackery Unmasked, nailed patent medicines as that industry headed toward its peak: The American people are great lovers of nostrums. They devour whatever in that line is new, with insatiable voracity. Staid Englishmen look on in astonishment. They call us pill-eaters and syrup-drinkers, and wonder at our fickleness and easy credulity; so that we have almost become a laughing-stock in the eyes of the world.

In 1815 news of peace reached New Orleans. A guy who heard it early made a deal to buy fifty tons of tobacco from a man who didn’t yet know the blockade was ending. The seller, feeling cheated afterward, sued the buyer, but in one of its most important early opinions, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously decided the plaintiff had no recourse: sorry, sucker, in this free market, buyer and seller beware. Telling less than the whole truth—hustling—had received a blanket indemnity. In commerce as in the rest of life, when it came to truth and falsehood, America was a free-fire zone.

By 1848, Americans’ appetite for the amazing and the incredible had been whetted by two decades of transformative technologies and by the manic fabulism of dime museums and medicine shows and newly sensationalist newspapers. A credulity about E-Z self-improvement—swallowing pills or feeling the Holy Spirit to end one’s suffering magically—had been normalized during the First Great Delirium.

We think of the Beats as un-American creatures, the anti-1950s exceptions who proved the rule. But they were highly American. For one thing, the founders became enduring pop celebrities. More important, their animating impulses grew out of that old American search for a sense of meaning that devolved into dreamy, grandiose unreasonableness.

This is what made the Beats such an American phenomenon. They were all about their mystical, individualist beliefs, and all in. They rejected bland rules to live lives of anti-materialist and quasi-religious purity. They were like some freaky renegade Protestant sect who didn’t focus on Jesus but otherwise took the original priesthood-of-all-believers idea to the max. The Beats’ self-conception descended from a particular American lineage—mountain men, outlaws, frontier cranks, lonely individualists, and narcissistic outsiders sounding their barbaric yawps over the rooftops of the world. The hippie dream that followed drew as well from a parallel lineage—Cane Ridge, the communes of the 1830s and ’40s, Transcendentalism, pastoralism, Thoreau. Both were enactments of classic American fantasies.

Like mesmerism and homeopathy in the nineteenth century, orgone therapy was an import from German Europe. Its inventor was the psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich, a protégé of Freud—who finally concluded Reich was nuts: he “salutes in the genital orgasm,” Freud wrote a colleague, as “the antidote to every neurosis.” He got nuttier, announcing he’d discovered fundamental new substances—“bions” and, after he emigrated to the United States, “primordial, pre-atomic cosmic orgone energy,” the very source of human vitality. In America he was taken seriously for a while and not just by the Beats. His work was cited in the major medical journals. Cancer victims came to be cured in his orgone accumulators. Farmers paid him to point his “cloudbuster” at the sky to unleash atmospheric orgone energy and make it rain, and he also said it’d work to ward off extraterrestrial invaders. He believed a secret cabal of highly placed allies in the federal government would save him from his enemies the Rockefellers, Communists, FDA, and Justice Department. The feds ordered him to stop advertising and selling his quack medical devices; he refused; they prosecuted and finally imprisoned him.

American religious leaders have always sold their crazy ideas by spinning off independent enterprises to promote them.

The new age has done the same thing, with millions more businesses. It too is a religion that has mystical and supernatural beliefs and a pursuit of truth, bliss, self-improvement, and prosperity. There are hundreds of New age start-ups, sects, practices, and prophets. It is Establishment even though it likes to think of itself as the opposite. It is yet another part of the fantasy-industrial religions, where none of us “are sticklers for reason”.

But unlike most religions, there isn’t a single supreme being or messiah.

Fake medicine techniques also sold politicians

William Henry Harrison was the first fully merchandised candidate. He had grown up rich and was the nominee of the elites’ Whig Party. But his spin doctors sold him to voters as the opposite—a common man, a rough regular guy, with on-message campaign songs and chants, one about his “homespun coat” and “no ruffled shirt.” They branded him with life-size and miniature log cabins, and they gave out whiskey in bottles shaped like log cabins and shaving soap called Log-Cabin Emollient

His opponent’s upbringing really had been humble, but he was the incumbent president and thus could be framed as an elitist. Harrison won by a landslide.

What was working for patent medicines also worked for a political candidate. And essential to both were the new, large-circulation newspapers and magazines that much faster, bigger, steam-powered presses had made possible. These cheap daily papers didn’t scruple about the advertising they published, and they had loose standards of accuracy and truth in their news reports as well. They were beacons of a new American audacity about blurring and erasing the lines between factual truth and entertaining make-believe.

From fake medicine to entrepreneur’s and hustlers

As with the American habit of wishfulness in general, a confirmation bias kicks in: from Ben Franklin to Mark Zuckerberg, the stories of the supremely successful entrepreneurs obscure the forgotten millions of losers and nincompoops.

A part of every entrepreneur’s job is to persuade and recruit others to believe in a dream, and often those dreams are pure fantasies. A defining feature of America from the start, according to McDougall’s Freedom Just Around the Corner, was the unprecedented leeway and success of its hucksters—“self-promoters, scofflaws, occasional frauds, and peripatetic self-reinventors,” as well as “builders, doers, go-getters, dreamers.” He writes that “Americans are, among other things, prone to be hustlers,

A large pool of hustlers to be successful, of course, requires a large population of easy believers.

Once there was an industry based on moving Americans west—the transcontinental railroads—a large and continuous stream of travelers and settlers was required to sustain those new entrepreneurial businesses. Which meant that the railroads and their allies needed to sell the settlers fantasies, as the original New World speculators had done to prospective Americans back in the 1600s. Occasional new discoveries of gold and silver could pull the most excitable, but the main lure was land, cheap or even free, and not just to tediously farm. All over the empty West, the promoters promised, land could make you rich.

A generation later more of my ancestors arrived in Nebraska from Denmark, right before the Panic of 1893. That financial panic, which triggered a huge economic depression, was caused in part by the unsustainable overbuilding of the western railroads and the popping of that railroad bubble. Which had been inflated by the western real estate bubble. Which happened even though just twenty years before, the Panic of 1873 had been caused by the popping of a previous railroad bubble. Americans, predisposed to believe in bonanzas and their own special luckiness, were not really learning the hard lessons of economic booms and busts.

Technology that seems magical and miraculous can encourage and confirm credulous people’s belief in make-believe magic and miracles. Yhe Fox sisters communicated with a ghost haunting their house by means of a kind of knock-knocking Morse code. (Like so many of my nineteenth-century characters, they were in western New York State, the next town over from where Joseph Smith first spoke to God.) The Fox sisters became famous mediums and helped launch a national movement of “spiritualists” communicating with the dead.

If some imaginary proposition is exciting, and nobody can prove it’s untrue, then it’s my right as an American to believe it’s true.

P. T. Barnum was the great early American merchandiser of exciting secular fantasies and half-truths. His extremely successful pre-circus career derived from and fed a fundamental Fantasyland mindset.

His American Museum’s combination of fake and real was more pernicious than if he’d exhibited sideshow humbug exclusively. For decades, it was at the respectable center of the new popular culture, reflecting and reinforcing Americans’ appetite for entertaining fibs and a disregard for clear distinctions between make-believe and authentic. And as Neal Gabler notes in Life: The Movie, “by the mid-nineteenth century the popular culture here was much vaster than in Europe and had permeated society much more deeply.” Barnum’s humbuggery was influential.

The pseudo-pharmaceutical industry, already booming, took his pop cultural big idea and made it both narrower and broader. Each traveling medicine show was devoted to selling a particular manufacturer’s patent medicines, but the shows appeared all over the country, especially in small towns. Whereas Barnum’s business model was straightforward and traditional—buy a ticket, be entertained—the innovation of the medicine show was closer to that of the advertising-dependent penny press: pay nothing to be entertained by musicians, magicians, comedians, and flea circuses in exchange for watching and listening to interstitial live advertisements for dubious medical products

One Response to Fantasyland 6. New Age, alternative medicine, and supernatural madness