Source: Republican Jesus

Source: Republican Jesus

Preface. This is a book review of One Nation Under God: How Corporate America Invented Christian America by Kevin Kruse (2016), followed by excerpts from the book. Much of this introduction is my take on what this all means.

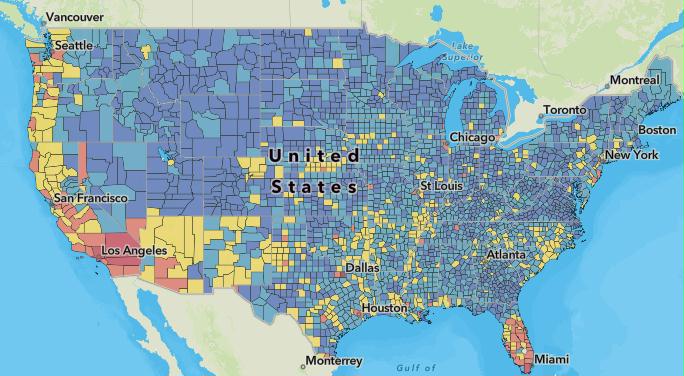

This book tells the history of how corporate America has tried to undo New Deal reforms since the 1940s by creating a new free-enterprise religion, and to erode the separation of church and state.

Corporate America’s creation of free-enterprise Jesus began in 1935 with the founding of an organization called Spiritual Mobilization. Some of the corporations who donated money to this and similar organizations include:

American Cyanamid and chemical corporation, Associated Refineries, AT&T, Bechtel Corporation, Caterpillar Tractor Company, Chevrolet, Chicago & Southern Airline, Chrysler corporation, Colgate-Palmolive Company, Deering-Milliken, Detroit Edison, Disney, DuPont, Eastern Airlines, General Electric, General Foods, General Motors, Goodwill, Goodyear Tire & Rubber, IBM, J. C. Penney, J. Walter Thompson, Mark A. Hanna, Marriott, Marshall Field, Monsanto Chemical Company, National Association of Manufacturers, Pacific Mutual Life Insurance, Paramount Pictures, PepsiCo, Precision Valve Corp, Quaker Oats, Republic Steel Corp, Richfield Oil Co., San Diego Gas & Electric, Schick Safety Razor, Standard Oil Company, Sun Oil company, Sun shipbuilding company, Union Carbide and Carbon Corporation, United Airlines, US Rubber company, US steel corporation, Utah Power & Light, Warner Bros. Pictures, Weyerhauser.

In the 1930s, corporations were well known to have brought on the Great Depression with their tremendous greed and dishonesty. The New Deal reformed the financial system, distributed wealth more evenly, provided a social safety net, protected citizens by regulating businesses to prevent them from selling unsafe food, drugs, etc., emitting toxic pollution, aided farmers in slowing soil erosion to prevent more dust bowls, the federal interstate highway system, and other infrastructure and public services that benefited everyone, especially corporations.

The New Deal embodied the ideals of the Social Gospel, a movement dedicated to the public good, economic equality, eradication of poverty, slums, child labor, an unclean environment, inadequate labor unions, poor schools, and war (Wiki Social Gospel).

Corporate America fought against these reforms and has been trying to undo the New Deal ever since then.

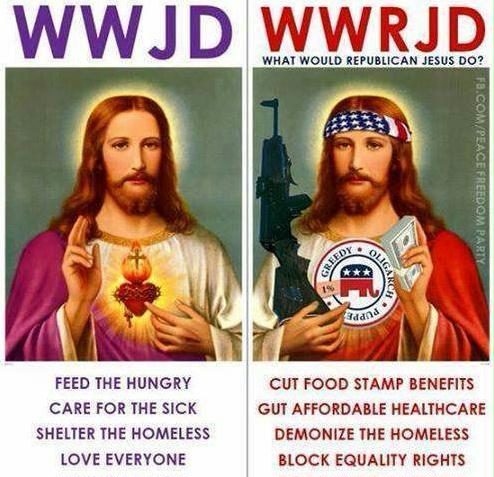

One of their most successful tactics was getting religious leaders to spout a new version of Jesus – replacing the Social Gospel Jesus of the New deal with a Republican free-enterprise, Ayn Rand, selfish Jesus.

At first everyone saw through this propaganda since it was obviously driven by craven self-interest.

So the propaganda was crafted more subtly, and sold to conservative religious leaders via what appeared to be a religious organization called “Spiritual Mobilization” run by minister James Fifield. Congregations began to hear sermons about the free-enterprise Jesus with open hearts and minds, which they would have laughed at if the speaker were from a corporation. The new religion taught them to detest unions, social welfare, and to fear and hate government.

Later on, capitalist Jesus expanded to the teachings of the evils of food stamps, Obamacare, to be against abortion and birth control (since the more people there are they less they can be paid). This propaganda came not just from the pulpit, but also conservative religious TV and radio stations.

Recent scholarship has revealed Jesus to be the Social Gospel Jesus of the Democrats in Rex Weyler’s book “The Jesus Sayings: The quest for his authentic message”. Weyler also found that people have been twisting the real Jesus since St. Paul, so Republican manipulation isn’t anything new, it’s been going on for 2000 years. By looking at the Dead Sea scrolls (found in the last century) and modern scholarship, Weyler found that the most likely Jesus was a man who spent his time helping the poor and encouraged people to turn their spiritual philosophy in to action. Jesus was a wise and humble teacher, advocating self-awareness and social compassion. The core, genuine message of Jesus includes (Solomon 2008): 1) Give to anyone who asks; knowledge and righteousness are revealed in action, 2) seek spiritual resources within yourself; don’t wait for a deity to solve your problem, and that knowing one’s self is the first step to offering comfort and compassion to the world.

This book shows how the Bible, America’s history, and Constitution were misquoted and misinterpreted to twist Jesus into Capitalist Jesus.

This is why you don’t have a chance of talking Uncle Bob out of voting for demagogues at the Thanksgiving table – you’re attacking his religion and core beliefs he’s been taught since his first sermon, and his brain shuts down in anger. And he’ll never change because the main and just about only social organization that knits rural American communities together is Church. If you read enough to doubt right-wing ideology and religious philosophy, you’re going to be a very lonely and perhaps even outcast person.

People like to say that capitalism is imperfect, but it’s the best system that exists. Well, I’ll agree that free-enterprise is better at raping, pillaging, and poisoning land, water, and air more quickly than any other system. Just look at how industrial farming is depleting aquifers and eroding and compacting top soil to the point where it won’t produce much food after just centuries rather than the average of 1,500 years in past civilizations (Montgomery 2007).

If Capitalism is so great, why are Social Gospel nations like Denmark, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, the Netherlands, and Canada consistently ranked the happiest nations in the world as well as high in the per capita nominal GDP rankings? Socialist Cuba did far better than other nations when their fossil fuels were suddenly cut, with Russia coming in second.

Alice Friedemann www.energyskeptic.com Women in ecology author of Life After Fossil Fuels: A Reality Check on Alternative Energy; When Trucks Stop Running: Energy and the Future of Transportation”, Barriers to Making Algal Biofuels, & “Crunch! Whole Grain Artisan Chips and Crackers”. Podcasts: WGBH, Crazy Town, Collapse Chronicles, Derrick Jensen, Practical Prepping, KunstlerCast 253, KunstlerCast278, Peak Prosperity

***

This book argues the postwar revolution in America’s religious identity had its roots in the domestic politics of the 1930s and early 1940s.

Decades before Eisenhower’s inaugural prayers, corporate titans enlisted conservative clergymen in an effort to promote new political arguments embodied in the phrase “freedom under God.”

As the private correspondence and public claims of the men leading this charge make clear, this new ideology was designed to defeat the state power its architects feared most—not the Soviet regime in Moscow, but Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal administration in Washington. With ample funding from major corporations, prominent industrialists, and business lobbies such as the National Association of Manufacturers and the US Chamber of Commerce in the 1930s and 1940s, these new evangelists for free enterprise promoted a vision best characterized as “Christian libertarianism.

By the late 1940s and early 1950s, this ideology had won converts including religious leaders such as Billy Graham and Abraham Vereide and conservative icons ranging from former president Herbert Hoover to future president Ronald Reagan. The new conflation of faith, freedom, and free enterprise then moved to center stage in the 1950s under Eisenhower’s watch.

Though his administration gave religion an unprecedented role in the public sphere, it essentially echoed and amplified the work of countless private organizations and ordinary citizens who had already been active in the same cause.

Corporate leaders remained central. Leading industrialists and large business organizations bankrolled major efforts to promote the role of religion in public life. The top advertising agency of the age, the J. Walter Thompson Company, encouraged Americans to attend churches and synagogues through an unprecedented “Religion in American Life” ad campaign.

Inundated with urgent calls to embrace faith, Americans did just that. The percentage of Americans who claimed membership in a church had been fairly low across the 19th century, increasing from just 16% in 1850 to 36% in 1900. In the early decades of the 20th century the percentages plateaued, remaining at 43% in both 1910 and 1920, then moving up slightly to 47% in 1930 and 49% in 1940. In the decade and a half after the Second World War, however, the percentage of Americans who belonged to a church or synagogue suddenly soared, reaching 57% in 1950 and then peaking at 69% at the end of the decade, an all-time high.

While this religious revival was remarkable, the almost complete lack of opposition to it was even more so. A few clergymen complained that the new public forms of faith seemed a bit superficial, but they ultimately approved of anything that encouraged church attendance.

IN DECEMBER 1940, MORE THAN 5,000 industrialists from across America took part in their yearly pilgrimage to Park Avenue. For three days every winter, the posh Waldorf-Astoria Hotel welcomed them for the annual meeting of the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM). Tucked away near the end of the program was a name that few knew upon arrival but everyone would be talking about by the week’s end: Reverend James W. Fifield Jr.

Ordinarily, a Congregationalist minister might not have seemed well suited to address the corporate luminaries assembled at the Waldorf-Astoria. But his appearance had been years in the making. For much of the 1930s, organizations such as NAM had been searching in vain for ways to rehabilitate a public image that had been destroyed in the crash and defamed by the New Deal. In 1934, a new generation of conservative industrialists took over NAM with a promise to “serve the purposes of business salvation.” “The public does not understand industry,” one of them argued, “because industry itself has made no effort to tell its story; to show the people of this country that our high living standards have risen almost altogether from the civilization which industrial activity has set up.” Accordingly, NAM dedicated itself to spreading the gospel of free enterprise, through a wide array of films, radio programs, advertisements, direct mail, a speakers bureau, and a press service that provided ready-made editorials and news stories for 7,500 local newspapers. By 1937 the organization devoted $793,043 to the cause, more than half its total income that year. Seeking to repair the image of industrialists, NAM promoted the values of free enterprise

Its efforts at self-promotion were seen as precisely that. As one observer noted, “Throughout the 30s, the corporate campaign was marred by extremist, overt attacks on the unions and the New Deal that it was easy for critics to dismiss the entire effort as mere propaganda.

While established business lobbies such as NAM had been unable to sell free enterprise effectively in the Depression, neither had the many new organizations created specifically for that purpose. The most prominent, the American Liberty League formed in 1934 to “teach the necessity of respect for the rights of persons and property” and “the duty of government to encourage and protect individual and group initiative and enterprise.” It benefited from generous financial support from corporate titans, particularly at DuPont and General Motors. But their prominence inadvertently crippled its effectiveness, as the Liberty League was easily dismissed as a collection of tycoons looking out for their own self-interest. Jim Farley, chairman of the Democratic Party, joked that it really ought to be called the “American Cellophane League” because “first, it’s a DuPont product and second, you can see right through it.” Even the president took his shots. “It has been said that there are two great Commandments—one is to love God, and the other to love your neighbor,” Franklin D. Roosevelt noted soon after its creation. “The two particular tenets of this new organization say you shall love God and then forget your neighbor.” Off the record, he joked that the name of the god they worshiped seemed to be “Property”.

In introducing the New Deal, Roosevelt and his allies revived the old language of the so-called Social Gospel to justify the creation of the modern welfare state. The original proponents of the Social Gospel, back in the late 19th century, had significantly reframed Christianity as a faith concerned less with personal salvation and more with the public good. They rallied popular support for Progressive Era reforms in the early 20th century before fading from public view in the conservative 1920s. But the economic crash and the widespread suffering of the Great Depression brought them back into vogue. When Roosevelt launched the New Deal, an array of politically liberal clergymen championed his proposal for a vast welfare state as simply “the Christian thing to do.” His administration’s efforts to regulate the economy and address the excesses of corporate America were singled out for praise. Catholic and Protestant leaders hailed the “ethical and human significance” of New Deal measures, which they said merely “incorporated into law some of the social ideas and principles for which our religious organizations have stood for many years.” The head of the Federal Council of Churches, for instance, claimed the New Deal embodied basic Christian principles such as the “significance of daily bread, shelter, and security.

Throughout the 1930s, the nation’s industrialists tried to counter the selflessness of the Social Gospel with direct appeals to Americans’ self-interest but had little success.

Accordingly, at the Waldorf-Astoria in December 1940, NAM president H. W. Prentis proposed that they try to beat Roosevelt at his own game. With wispy white hair and a weak chin, the 56-year-old head of the Armstrong Cork Company seemed an unlikely star. But 18 months earlier, the Pennsylvanian had electrified the business world with a speech to the US Chamber of Commerce that called for the recruitment of religion in the public relations war against the New Deal. “Economic facts are important, but they will never check the virus of collectivism,” Prentis warned; “the only antidote is a revival of American patriotism and religious faith.” The speech thrilled the Chamber and propelled Prentis to the top ranks of NAM. His presidential address at the Waldorf-Astoria was anticipated as a major national event, heavily promoted in advance by the Wall Street Journal and broadcast live over both ABC and CBS radio. Again, Prentis urged the assembled businessmen to emphasize faith in their public relations campaigns. “We must give attention to those things more cherished than material wealth and physical security,” he asserted. “We must give more attention to intellectual leadership and a strengthening of the spiritual concept that underlies our American way of life.

Fifield delivered a passionate defense of the American system of free enterprise and a withering assault on its perceived enemies in government. Decrying the New Deal’s “encroachment upon our American freedoms,” the minister listed a litany of sins committed by the Roosevelt administration, ranging from its devaluation of currency to its disrespect for the Supreme Court. He denounced the “rising costs of government and the multitude of federal agencies attached to the executive branch” and warned ominously of “the menace of autocracy approaching through bureaucracy.” His audience of executives was stunned. Over the preceding decade, these titans of industry had been told, time and time again, that they were to blame for the nation’s downfall.

Fifield, in contrast, insisted that they were the source of its salvation.

Minister Fifield convinced the industrialists that clergymen could be the means of regaining the upper hand in their war with Roosevelt in the coming years. As men of God, they could give voice to the same conservative complaints as business leaders, but without any suspicion that they were motivated solely by self-interest. In doing so, they could push back against claims that business had somehow sinned and the welfare state was doing God’s work.

Conservative clergymen now used their ministerial authority to argue, quite explicitly, that New Dealers were the ones violating the Ten Commandments. In countless sermons, speeches, and articles issued in the months and years after Fifield’s address, these ministers claimed that the Democratic administration made a “false idol” of the federal government, leading Americans to worship it over the Almighty; that it caused Americans to covet what the wealthy possessed and seek to steal it from them; and that, ultimately, it bore false witness in making wild claims about what it could never truly accomplish.

Above all, they insisted that the welfare state was not a means to implement Christ’s teachings about caring for the poor and the needy, but rather a perversion of Christian doctrine. In a forceful rejection of the public service themes of the Social Gospel, they argued that the central tenet of Christianity remained the salvation of the individual. If any political and economic system fit with the religious teachings of Christ, it would have to be rooted in a similarly individualistic ethos. Nothing better exemplified such values, they insisted, than the capitalist system of free enterprise.

He and his colleagues devoted themselves to fighting back against the government forces that they believed were threatening capitalism and, by extension, Christianity. In the early postwar era, their activities helped reshape the national debate about the proper functions of the federal government, the political influence of corporations, and the role of religion in national life.

Fifield had watched in alarm as Roosevelt convinced vast majorities of Americans that unfettered capitalism had crippled the nation and that the federal government now needed to play an important new role in regulating the free market’s risks and redistributing its rewards. For Fifield and his flock, Roosevelt’s actions violated not just the Constitution but the natural order of things.

The New Deal undermined the spirit of Christianity and demanded a response from Christ’s representatives on earth. “If, with Jesus, we believe in the sacredness of individual personalities, then our leadership responsibility is very plain.” This duty was “not an easy one,” he cautioned. “We may be called unpatriotic and accused of ‘selling out,’ but so was Jesus.” Finding the leaflet to his liking, Hoover sent Fifield a warm note of appreciation and urged him to press on.

Though they had hoped to destroy the Roosevelt administration themselves, its wounds were largely self-inflicted. In 1937, the president’s labor allies launched a series of sit-down strikes that secured union recognition at corporations such as General Motors and US Steel but also roused sympathy for seemingly beleaguered businessmen. At the same time, Roosevelt overreached with his proposal to “pack” the Supreme Court with new justices, a move that played into the hands of those who sought to portray him as dictatorial in intent. Most significant, though, was his ill-fated decision to rein in federal spending in an effort to balance the budget. The impressive economic recovery of Roosevelt’s first term suddenly stalled, and the country entered a short but sharp recession in the winter of 1937–1938.

As the New Deal faltered, Fifield began to look forward to the next presidential election—in “the critical year 1940”—when conservatives might finally rout the architects of the regulatory state. To his dismay, international tensions soon marginalized domestic politics and prompted the country to rally around Roosevelt again.

As the distraction of the foreign war drew to a close, Fifield looked forward to renewing the fight against the New Deal. The minister now counted on the support of not just Hoover but an impressive array of conservative figures in politics, business, and religion. The advisory committee for Spiritual Mobilization’s wartime pledge was, in the words of one observer, “a who’s who of the conservative establishment.” At mid-decade, its 24-man roster included three past or present presidents of the US Chamber of Commerce, a leading Wall Street analyst, a prominent economist at the American Banking Association, the founder of the National Small Businessmen’s Association,

Senator Albert Hawkes agreed. “After careful examination of the records during the past ten years, one can only conclude that there is the objective of the assumption of greater power and control by the government over individual life. If these policies continue,” he warned, “they will lead to state direction and control of all the lives of our citizens. That is the goal of Federal planners. That is NOT the desire of the American people!

In February 1945, Haake explained to Pew why the NAM campaign to ministers and others like it had all failed. “Of the approximately 30 preachers to whom I have thus far talked, I have yet to find one who is unqualifiedly impressed,” Haake reported. “One of the men put it almost typically for the rest when he said: ‘The careful preparation and framework for the meetings to which we are brought is too apparent. We cannot help but see that it is expertly designed propaganda and that there must be big money behind it.

If industrialists wanted to convince clergymen to side with them, they would need a subtler approach. Rather than simply treating ministers as a passive audience to be persuaded, Haake argued, they should involve them actively in the cause as participants. The first step would be making ministers realize that they too had something to fear from the growth of government. “The religious leaders must be helped to discover that their callings are threatened,” Haake argued, by realizing that the “collectivism” of the New Deal, “with the glorification of the state, is really a denial of God.” Once they were thus alarmed, they would readily join Spiritual Mobilization as its representatives and could then be organized more effectively into a force for change both locally and nationally.

With the new financial support and sense of direction, Spiritual Mobilization underwent a massive overhaul. In February 1947, Fifield reported that he had already reached their goal for “the signing of 10,000 ministers as representatives.” This national network of clergymen would be the primary channel through which the work and writings of Spiritual Mobilization would flow. In a new monthly publication that bore the organization’s name, Fifield ran a column—with the businesslike heading “Director to Representatives”—devoted to marshaling these ministers to achieve their common goal of defeating the New Deal. Fifield repeatedly warned them that the growth of government had crippled not only individual initiative but personal morality as well. “It is time to exalt the dignity of individual man as a child of God, to exalt Jesus’ concept of man’s sacredness and to rebuild a moral fabric based on such irreducibles as the Ten Commandments,” he urged his minister-representatives.

Clergymen responded enthusiastically. Many ministers wrote the Los Angeles office to request copies of Friedrich Hayek’s libertarian treatise The Road to Serfdom and anti–New Deal tracts by Herbert Hoover and libertarian author Garet Garrett, all of which had been advertised in Spiritual Mobilization. Some sought reprints of the bulletin itself.

Fifield’s backers in the Businessmen’s Advisory Committee were so pleased with his progress that they nearly doubled the annual budget. To raise funds, its members secured sizable donations from their own companies and personal accounts and, more important, reached out to colleagues across the corporate world for their donations as well. Pew once again set the pace, soliciting donations from officials at 158 corporations. “A large percentage of ministers in this country are completely ignorant of economic matters and have used their pulpits for the purpose of disseminating socialistic and totalitarian doctrines,” he wrote in his appeal. “Much has already been accomplished in the education of these ministers, but a great deal more is left to be done.” Many of the corporations he contacted—including General Motors, Chrysler, Republic Steel, National Steel, International Harvester, Firestone Tire and Rubber, Sun Oil, Gulf Oil, Standard Oil of New Jersey, and Colgate-Palmolive-Peet—were already contributing the maximum allowable annual donation. Other leading businesses, from US Steel to the National Cash Register Company, had donated in the past, but Pew hoped they would commit to the limit as well. Recognizing that there were many conservative groups out there “fighting for our American way of life,” Pew assured a colleague in the oil industry that Spiritual Mobilization deserved to be “at the top of the list” when it came time to donate, “because recent polls indicated that of all the groups in America, the ministers had more to do with molding public opinion.

“According to my book there are five principal issues before the country: The socialization of industry, the socialization of medicine, the socialization of education, the socialization of labor, and the socialization of security,” he noted. “Only through education and the pressure which the people exert on their politicians can we hope to prevent this country from becoming a totalitarian state.

Fifield’s financial backers helped secure free airtime for these programs across the nation. “Republic Steel is taking steps to get them on radio stations in every town where they have a factory or office,” Fifield noted in March 1949. “We are expecting to be on 150 radio stations by June.” A year later, The Freedom Story was broadcast on a weekly network of over 500 stations; by late 1951, it aired on more than 800.

Fifield’s journal purposely presented itself as created by ministers for ministers. Spiritual Mobilization had long operated on the principle that clergymen could not be swayed through crude propaganda. “The articulation should be worked out before-hand, of course, and we should be ready to help the thinking of the ministers on it,” Haake noted in one of his early musings on Spiritual Mobilization, “but it should be so done as to enable them to discover it for themselves, as something which they really had believed but not realized fully until our questions brought it out so clearly. I am sure we may not TELL them: not as laymen, or even as fellow clergymen. We must help them to discover it themselves.

Faith and Freedom thus presented itself as an open forum in which ministers could debate a wide variety of issues and disagree freely. But there was an important catch. “Clergymen may differ about politics, economics, sociology, and such,” Fifield stated, “but I would expect that in matters of morality all followers of Jesus speak in one voice.” Because Fifield and Johnson insisted that morality directly informed politics and economics, they were able to cast those who disagreed with them on those topics as essentially immoral

Time and time again, he condemned a variety of “socialistic laws,” such as ones supporting minimum wages, price controls, Social Security pensions for the elderly, unemployment insurance, veterans’ benefits, and the like, as well as a wide range of federal taxation that he deemed to be “tyrannical” in nature.

As the Fourth of July drew near, the Committee to Proclaim Liberty focused its attention on encouraging Americans to mark the holiday with public readings of the preamble to the Declaration of Independence. The decision to focus solely on the preamble was in some ways a natural one, as its passages were certainly the most famous and lyrical in the document. But doing so also allowed organizers to reframe the Declaration as a purely libertarian manifesto, dedicated to the removal of an oppressive government. Those who read the entire document would have discovered, to the consternation of the committee, that the founding fathers followed the high-flown prose of the preamble with a long list of grievances about the absence of government and rule of law in the colonies. Among other things, they lambasted King George III for refusing “his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good,” for forbidding his governors from passing “Laws of immediate and pressing importance,” for dissolving the legislative bodies in the colonies, and for generally enabling a state of anarchy that exposed colonists to “all the dangers of invasion from without, and convulsions within.” In the end, the Declaration was not a rejection of government power in general but rather a condemnation of the British crown for depriving the colonists of the government they needed. In order to reframe the Declaration as something rather different, the Committee to Proclaim Liberty had to edit out much of the document they claimed to champion.

“. . . That to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men . . .” Here is the reason for and the purpose of government. Government is but a servant—not a master—not a giver of anything. “. . . deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed . . .” In America, the government may assume only the powers you allow it to have. It may assume no others. The ad urged readers to make their own declaration of independence in 1951. “Declare that government is responsible TO you—rather than FOR you,” it continued. “Declare that freedom is more important to you than ‘security’ or ‘survival.’

“The effort to establish socialism in our country has probably progressed farther than most of us fully realize,” asserted a Lutheran minister in Kansas. “It would be well to remember that every act or law passed by which the government promises to ‘give’ us something is a step in the direction of socialism.” A clergyman from Brooklyn agreed. “Today our homes are built for us, financed for us, and the church is provided for us. Our many services are in danger of robbing us of that which is most important,” he warned, “the right to our own kingdom of self.

Americans had learned that the Soviet Union now had the atomic bomb. The energetic young Graham seized on the headlines to make the Armageddon foretold in the New Testament seem imminent. “Communism,” he thundered, “has decided against God, against Christ, against the Bible, and against all religion. Communism is not only an economic interpretation of life—communism is a religion that is inspired, directed, and motivated by the Devil himself who has declared war against Almighty God.” He urged his audience to get religion not simply for their own salvation but for the salvation of their city and country. Without “an old-fashioned revival,” he warned, “we cannot last!

Three important movements in the 1940s and early 1950s—the prayer breakfast meetings of Abraham Vereide, Graham’s evangelical revivals, and the presidential campaign of Dwight D. Eisenhower—encouraged the spread of public prayer as a political development whose means and motives were distinct from the drama of the Cold War. Working in lockstep to advance Christian libertarianism, these three movements effectively harnessed Cold War anxieties for an already established campaign against the New Deal.

Graham was the most prominent of the new Christian libertarians, a charismatic figure who spread the ideas of forerunners such as Fifield to even broader audiences. In 1954, Graham offered his thoughts on the relationship between Christianity and capitalism in Nation’s Business, the magazine of the US Chamber of Commerce. “We have the suggestion from Scripture itself that faith and business, properly blended, can be a happy, wholesome, and even profitable mixture,” he observed. “Wise men are finding out that the words of the Nazarene: ‘Seek ye first the kingdom of God and His righteousness, and all these things shall be added unto you’ were more than the mere rantings of a popular mystic; they embodied a practical, workable philosophy which actually pays off in happiness and peace of mind. . . . Thousands of businessmen have discovered the satisfaction of having God as a working partner.

Graham’s warm embrace of business contrasted sharply with the cold shoulder he gave organized labor. The Garden of Eden, he told a rally in 1952, was a paradise with “no union dues, no labor leaders, no snakes, no disease.” The minister insisted that a truly Christian worker “would not stoop to take unfair advantage” of his employer by ganging up against him in a union. Strikes, in his mind, were inherently selfish and sinful. If workers wanted salvation, they needed to put aside such thoughts and devote themselves to their employers.

On Labor Day that same year, he warned that “certain labor leaders would like to outlaw religion, disregard God, the church, and the Bible,” and he suggested that their rank and file were wholly composed of the unchurched.

His hostility to organized labor was matched by his dislike of government involvement in the economy, which he invariably condemned as “socialism.” Graham warned that “government restrictions” in the realm of free enterprise threatened “freedom of opportunity” in America.

Graham’s thoughts on the dangers of socialism became a bit of an international scandal after the Billy Graham Evangelical Association sent followers a free calendar. A page on England noted that “when the war ended a sense of frustration and disillusionment gripped England and what Hitler’s bombs could not do, socialism with its accompanying evils shortly accomplished. England’s historic faith faltered. The churches still standing were gradually emptied.” Learning of the slight, a columnist for the London Daily Herald denounced Graham with a new nickname: “the Big Business evangelist.

As preachers like Billy Graham helped to popularize public prayer, they thus managed to politicize it as well. They shared the Christian libertarian sensibilities of Spiritual Mobilization but were able to spread that gospel in much subtler—and much more effective—ways than that organization ever could. At the same time, their work helped to democratize the phenomenon of public prayer.

Congressional breakfast meetings quickly became a fixture on Capitol Hill. Each month, Vereide printed a program to guide the groups in their morning meditations, offering specific readings from Scripture and providing questions for discussion. The groups were officially nonpartisan, welcoming Republicans and Democrats alike, but that was not to say they were apolitical. Most of the Democratic members of the House breakfast group, for instance, were conservative southerners who held federal power and the activism of the New Deal state in as much contempt as the average Republican did. Political overtones were lightly drawn but present nonetheless. “The domestic and the world conflict is the physical expression of a perverted mental, moral and spiritual condition,” noted a program for a House session. “We need to repent from our unworkable way and pray.” The congressional prayer meetings gave Vereide immediate access to the nation’s political elite.

Having won over political leaders in Washington, D.C., Vereide used their influence to establish even more breakfast groups across the nation. The minister pressed ahead in his drive to give the organization an international presence, with quick success. Within a few years, Christian Leadership breakfast groups were meeting regularly in 31 foreign countries. England, France, West Germany, the Netherlands, and Finland represented the bulk of the initial growth of the group, but the ICCL made its presence felt in nations as varied as China, South Africa, and Canada, with isolated operations in localities such as Havana and Mexico City as well. Vereide recognized that the tensions of the Cold War could be exploited to win more converts to his cause.

The earthy Richardson had little use for Graham’s religion, but the two shared a common faith in free enterprise. “When Graham speaks of ‘the American way of life,’” an early biographer noted, “he has in mind the same combination of economic and political freedom that the National Association of Manufacturers, the United States Chamber of Commerce, and the Wall Street Journal do when they use the phrase.

He chided Democrats for wasting money on the welfare state at home and the Marshall Plan abroad. “The whole Western world is begging for more dollars,” he noted that fall, but “the barrel is almost empty. When it is empty—what then?” He insisted that the poor in other nations, like those in his own, needed no government assistance. “Their greatest need is not more money, food, or even medicine; it is Christ.

Graham led prayer meetings all over town, including daily sessions in the Pentagon auditorium. On Monday mornings, he held “Pastor’s Workshops” with local clergymen; on Tuesdays, there were luncheons at the Hotel Statler to discuss religion with “the men who have so much a part in shaping the destiny of the Capital of Western Civilization: the business men of Washington.

EISENHOWER SEEMED AN UNLIKELY CANDIDATE to lead the nation to spiritual reawakening. For decades he had remained distant from religion and could not even claim a specific denominational affiliation. His grandfather had been a minister for the River Brethren, an offshoot of the Mennonites, and his father maintained that faith.

While he lacked ties to any specific denomination, Eisenhower remained firmly committed to the Bible itself. Like his parents, he considered it an unparalleled resource. One of his aides during the Second World War remembered that Eisenhower could “quote Scripture by the yard,” using it to punctuate points made at staff meetings.

Graham’s spiritual support was surely influential in the general’s decision, as was the financial support Richardson promised. Once Eisenhower announced his intentions, the oilman put his vast fortune to work for him. Richardson’s direct contribution to the campaign was reportedly $1 million, but he also paid for roughly $200,000 in expenses at the Commodore Hotel in New York, where the general had established offices after returning home, and then covered most of his expenditures during the Republican National Convention in Chicago as well.

Eisenhower condemned a set of “evils which can ultimately throttle free government,” which he identified as labor unrest, runaway inflation, “excessive taxation,” and the “ceaseless expansion” of the federal government. These were commonplace conservative positions, but Eisenhower presented them in religious language that elevated them for his audience.

Faith and Freedom followed the lead of Graham and Vereide, claiming it would never endorse one party or the other. But it offered a “political checklist for Christians” that nudged readers rather strongly toward the Republicans.

He took more than 55% of the popular vote, with even more impressive margins in the Electoral College, where he won 442 to 89. Stevenson only managed to win nine states.

Reflecting on the election returns, Eisenhower resolved to put that mandate in the service of a national religious revival. He asked Graham to meet with him in the suite Sid Richardson had provided at the Commodore Hotel in New York, to discuss plans for his inauguration and beyond. “I think one of the reasons I was elected was to help lead this country spiritually,” the president-elect confided.

“These days I seem to have no trouble filling my calendar,” the president-elect told them. “But this is one engagement that I requested. I wanted to come and do my best to tell those people who are my friends, who are supporters of the idea that is represented in the foundation, how deeply I believe that they are serving America.” The basic idea of the Freedoms Foundation was that those who promoted “a better understanding of the American way of life” should be singled out for awards and attention, especially those who celebrated the central role played by “the American free enterprise system” in making the nation great. Fittingly, for an organization devoted to the promotion of big business, its president was Don Belding, head of a national advertising agency whose clients included Walt Disney and Howard Hughes. The board of directors, meanwhile, included leaders at General Foods, Maytag, Republic Steel, Sherwin Williams, Union Carbide and Carbon, and US Rubber, as well as individuals such as Sid Richardson and Mrs. J. Howard Pew. The corporate presence was so pronounced that one honoree sent his award back, grumbling that the Freedoms Foundation was “just another group promoting the propaganda of the National Association of Manufacturers.

More than any other individual, Senator Frank Carlson deserved credit for creating the National Prayer Breakfast. An outspoken opponent of the New Deal, he denounced Franklin Roosevelt as the “destroyer of human rights and freedom” for his administration’s interventions in the economy. He held Harry Truman in similar contempt. “Little Caesars walk the highways of our nation, trying to tell us what to wear, eat, plant, sow and reap,” Carlson complained in 1947.

As Eisenhower’s cabinet focused its attention on spiritual rewards yet to come, its members faced the danger that the press and the public might focus more on the earthly riches they had already amassed. Secretary of Defense Charles Wilson had been the country’s highest-paid executive as president of General Motors, the world’s largest private corporation. Wilson’s initial refusal to divest his holdings in the corporation, which had nearly $5 billion worth of contracts with the same federal department he would now lead, had delayed his confirmation and tarnished his image. When asked whether his GM holdings would tempt him to favor his corporation over his nation, Wilson famously answered that he always thought “what was good for our country was good for General Motors, and vice versa.” The auto tycoon eventually agreed to release his shares, but he was not the only top Defense Department official whose business associations gave the appearance of impropriety. Deputy Secretary Roger Kyes had been in charge of procurement for General Motors; Secretary of the Army Robert Ten Broeck Stevens’s family textile company made uniforms for that branch of the military; Secretary of the Air Force Harold Talbott had ties to both Chrysler and North American Aviation; and Secretary of the Navy Robert Anderson—put in the post at Sid Richardson’s recommendation—had previously managed a major facility for Associated Refineries.

Though he attracted a considerable deal of scrutiny, Wilson was by no means the only corporate titan in the Eisenhower cabinet. Treasury Secretary George Humphrey, for instance, had long served as president of the Mark A. Hanna Company of Cleveland, a sprawling conglomerate with interests in coal, oil, natural gas, iron, steel, copper, rayon, plastics, shipping, and banking. Commerce Secretary Sinclair Weeks, a New England financier and banker, was such a zealous advocate for business that Eisenhower privately worried that he “seems so completely conservative in his views that at times he seems to be illogical.” Postmaster General Arthur Summerfield ran one of the nation’s largest automobile agencies but also found success in real estate, oil, and insurance, while Hobby had made her fortune as a Texas newspaper publisher. Although not businessmen themselves, both Dulles and Brownell had close ties to the corporate world from their time at two of New York’s oldest law firms; Dulles had reportedly earned more in billings than any other corporate attorney in America.

Business leaders, of course, had long been working to “merchandise” themselves through the appropriation of religion. In organizations such as Spiritual Mobilization, the prayer breakfast groups, and the Freedoms Foundation, they had linked capitalism and Christianity and, at the same time, likened the welfare state to godless paganism.

After decades of work, these businessmen believed their efforts had finally paid off with the election of Dwight Eisenhower. Watching him enthusiastically embrace public faith, these supporters assumed that the national religious revival was largely a means to a more important end: the rollback of the New Deal state. But they soon realized that, for all his sympathies for and associations with business leaders, Eisenhower saw the religious revival itself as his essential domestic duty. To their amazement, once in office he gave relatively little thought to the political and economic causes that his backers had always seen as the real reason for that revival.

He refused to go further, especially when it came to the welfare state that his supporters had long worked to destroy. Despite his personal sympathies with their position, the president believed “the mass of the people” disagreed. “Should any political party attempt to abolish social security, unemployment insurance, and eliminate labor laws and farm programs, you would not hear of that party again in our political history,” he warned. “There is a tiny splinter group, of course, that believes you can do these things. Among them are H. L. Hunt . . . , a few other Texas oil millionaires, and an occasional politician or business man from other areas. Their number is negligible and they are stupid.

Even though Eisenhower’s rise to power had depended on support from “Texas oil millionaires” such as Sid Richardson, he refused to roll back the welfare state they despised. In fundamental ways, he ensured the longevity of the New Deal, giving a bipartisan stamp of approval to its continuation and significantly expanding its reach. Notably, Eisenhower pushed Congress to extend Social Security coverage to another ten million Americans and increase benefits as well. In his first term, the president repeatedly resisted calls from conservatives to cut education spending; in his second, he secured an additional $1 billion for the cause. On a much larger scale, Eisenhower established the single largest public works project in American history with the interstate highway system, but did little to bring down tax rates for the wealthy; the top bracket barely dipped, declining from 94% to 92% over the course of his two terms in office.

For conservatives who had assumed that the success of “under-God consciousness” during the Eisenhower administration would naturally lead to tangible reductions in the welfare state, his time in office was a disappointment.

The National Association of Evangelicals (NAE) praised the president for the pious example he had set.

As with earlier drives to supplant the secular authority of the welfare state with the higher power of the Almighty, the Seven Divine Freedoms ultimately served an earthly purpose. Organizers made the political aims of the project explicit in their plans. “There is a growing realization that the enemies of freedom are not foreign powers,” observed R. L. Decker, the NAE’s executive director, “but that there are forces at work within the nation which are just as dangerous and more sinister than any foreign foe. These forces take advantage of the natural desires of the people for unity and security and material prosperity to propose panaceas for our social, economic, and political problems which, if accepted, would rob us of our freedom as effectively as defeat in warfare,” he continued.

The group would encourage public and private leaders to sign the “Statement of Seven Divine Freedoms” and thereby signify that the United States of America had been founded on the principles of the Holy Bible. Eisenhower was the first to sign, in an Oval Office ceremony on July 2, 1953. “This is the kind of thing I like to do,” he said afterward. “This statement is simple and understandable, and sets forth the basic truth which is the foundation of our freedoms.” Nixon added his name next, as did members of the cabinet.

“By means of the radio, motion pictures, television, newspaper and periodical advertisements, signboards and posters, essay contests and amateur dramatics as well as community rallies, sermons and editorials,” Decker insisted, “this theme ‘Freedom is of God and we must have faith in him’ can constantly be dinned into the consciousness of America

The Judiciary Committee sat to consider a proposed amendment to the Constitution of the United States. If passed, it would have declared, “This Nation devoutly recognizes the authority and law of Jesus Christ, Saviour and Ruler of nations through whom are bestowed the blessings of Almighty God.”1 The campaign for this “Christian amendment” had been under way, in fits and starts, for nearly a century. Like most efforts to add religious elements to American political culture, the idea originated during the Civil War. In 1861, several northern ministers came to believe that the conflict was the result of the godlessness of the Constitution. “We are reaping the effects of its implied atheism,” they warned, and only a direct acknowledgment of Christ’s authority could correct such an “atheistic error in our prime conceptions of Government.

These clergymen banded together to create the National Reform Association, an organization that was single-mindedly dedicated to promoting the Christian amendment. It won the support of prominent governors, senators, judges, theologians, college presidents, and professors.

Advocates of the Christian amendment still faced an inherently difficult challenge in the Senate. By its very nature, their proposal to change the Constitution forced them to acknowledge that the religious invocation was something new for the document. The founding fathers had felt no need to acknowledge “the law and authority of Jesus Christ,” and neither had subsequent generations of American legislators. Some of the more imaginative advocates of the Christian amendment at the Senate hearings simply waved away this history and argued that leaders such as Washington and Lincoln had supported the idea even if they never acted upon it. For evidence, they repeatedly made reference in their testimony to letters and meetings in which these presidents allegedly had lent support to their cause. At the hearings, the presiding senator kindly offered to have these documents inserted into the official transcript once they were found. But the published record provided a quiet rebuke to such claims, noting that inquiries to the Library of Congress and other authoritative sources showed that the alleged documents did not, in fact, exist.

Disneyland’s dedication testified to how deeply piety and patriotism were intertwined in its creator’s worldview. Disney, a Congregationalist, relied on Christianity as a constant guide. His faith in his country was equally strong, though his political beliefs changed considerably over the course of his life. During the 1930s, he had been a strong supporter of Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal. His cartoons during the Depression helped establish the so-called “sentimental populism” of the era’s popular culture, always championing “little guys”—Mickey Mouse, the Three Little Pigs, the Seven Dwarves—in their struggles against stronger foes. But in the 1940s, Disney’s politics took a sharp turn to the right. In 1941, a bitter strike at his company led him to denounce “Communist agitation” in a full-page ad in Variety. The day after Pearl Harbor, Disney was stunned when the US Army abruptly commandeered his studio for seven months’ use as a supply base. During the war, the government never paid him for some propaganda shorts he made, and his overseas profits dwindled to a trickle. Disney emerged from the conflict a staunch conservative. He helped bring the House Un-American Activities Committee to Hollywood in October 1947 and, in his appearance as a friendly witness, condemned communist influence in labor unions, pointedly naming names. When fellow Congregationalist James Fifield organized the Committee to Proclaim Liberty a few years later, Disney readily signed on to support its “Freedom Under God” festivities.

In its conflation of piety and patriotism, Disneyland embodied larger currents in American popular culture during the postwar era. Political leaders and religious reformers led the way in fomenting the religious revival of the Eisenhower era, but their counterparts in Hollywood and on Madison Avenue proved to be indispensable allies. Prompted by both patriotism and an eye for profits, entertainers and advertisers did a great deal to promote public expressions of faith in the era. Prominent advertising agencies promoted religious observance as a vital part of American life and religion as an essential marker of the national character.

Like much of corporate America, the advertising industry discovered religion as a means of professional salvation in the aftermath of the Great Depression. The industry had fallen into turmoil when ad revenues plummeted along with corporate profits in the crash of the late 1920s and early 1930s. More ominously for advertising executives, the New Deal represented the first real efforts to regulate their work, as it empowered the Federal Trade Commission to fight false claims about food and drugs. As the nation prepared itself for the Second World War, further growth of the federal government seemed guaranteed. Thus, in November 1941, hundreds of ad executives gathered at a spa in Hot Springs, Virginia, to discuss the danger of “those who would do away with the American system of free enterprise” or who might “modify the economic system of which advertising is an integral part.

The Advertising Council classified its projects as acts of public service, but in truth they were acts of public relations, meant to sell the American people on the merits of free enterprise. In 1946, for instance, the council launched a campaign titled “Our American Heritage.” On the surface, it seemed wholly nonpartisan, simply intended to raise Americans’ awareness of their rights and responsibilities as citizens. Internally, though, organizers described it as a conservative-minded effort that would help Americans resist becoming “pawns of a master state.

The J. Walter Thompson Company (JWT), the largest advertising firm in the world, handled the practical work of the campaign. Its advertisements had a simple message for Americans: go to church. Copywriters drew on their conventional strategies, pitching religion as a path to personal improvement and self-satisfaction. “Find yourself through faith,” the campaign urged; “come to church this week.” Ads typically dramatized the concerns of a frantic father or an anxious housewife and then, in the same tones used to hawk antacid or mouthwash, promised that faith would cure their problems quickly.

Television and film followed the religious trend throughout the 1950s. Billy Graham’s Hour of Decision program was televised by three different networks, on some 850 stations, to an estimated audience of twenty million viewers.

The most lasting legacy of The Ten Commandments was its marketing campaign. As he prepared for the debut, DeMille worked with the Fraternal Order of Eagles on an ambitious plan to establish monuments of the Ten Commandments on public property across the nation. The organization had been distributing copies of the Ten Commandments for years, inspired by an incident in which Judge E. J. Ruegemer of St. Cloud, Minnesota, learned that a juvenile defendant in his courtroom had never heard of the laws and “sentenced” the boy to learn and obey them. Ruegemer, the head of the Eagles’ Youth Guidance Commission, persuaded the fraternal order to take up the cause. Members and their families volunteered to make reproductions of the Ten Commandments, initially manufacturing them as paper scrolls in St. Paul and framing them with hand-cut wood and glass. The nearly nine hundred thousand members of the organization popularized the venture, distributing scrolls far and wide. Recipients included city halls in small towns from Washington State to Pennsylvania, judges in Idaho and Massachusetts, and a police detective in Atlantic City, New Jersey.

When he learned of the Eagles’ campaign, DeMille immediately wanted to join in. A consummate showman, the director urged the Eagles to work on a grander scale. Instead of modest scrolls, he suggested the organization craft larger stone monuments that more closely resembled the tablets described in Exodus. Together, DeMille and the Eagles established Ten Commandments monuments across America.

Schwarz capitalized on his new influence in Congress to present himself as a leading authority on the problem of communism and the solution of Christianity. In 1957, he addressed a breakfast meeting of the Republican Club, where he so inspired attendees that they “immediately,” as one told Schwarz, took steps “to refer you to the House Un-American Activities Committee and to arrange a personal interview between you and an Assistant to the President of the United States.” He was soon summoned to testify before the committee’s staff on the topic “The Communist Mind.” In an interview that ran for an hour and twenty minutes, the doctor—who liked to compare himself to a pathologist in his new line of work—patiently led congressional aides through his diagnosis of the communist menace. Ultimately, he urged greater awareness of “the basic foundations of American civilization” as the only cure.

Improbably, Schwarz’s congressional testimony quickly became a cause célèbre. The first transcripts were rapidly distributed, forcing Congress to print another 50,000 copies the following year. Executives at the Allen-Bradley Company, an electronics corporation in Milwaukee, published large portions of the interview as a special double-page advertisement in the largest metropolitan newspapers. “WILL YOU BE FREE TO CELEBRATE CHRISTMAS IN THE FUTURE?” the headline blared. “NOT UNLESS: You and other free Americans begin to understand and appreciate the benefits provided by God under the American free enterprise system.” The ad urged Americans to read Schwarz’s words and share them with friends. Much like the other corporations who sponsored like-minded messages, the Allen-Bradley Company insisted it had nothing to gain. “With this advertisement,” the sponsor noted, “this company is trying to sell you nothing except the importance of holding fast to your American freedoms including the freedom to live, the freedom to worship your God, and the freedom to work as you choose.” Republican senator Barry Goldwater, meanwhile, wrote Schwarz soon repackaged his testimony as a best-selling book, You Can Trust the Communists ( . . . To Do Exactly as They Say). Released in 1960, it quickly sold a million copies. While Schwarz successfully spread his message in print, his energies were more devoted to a whirlwind tour of personal appearances.

In 1958, the CACC launched its first School of Anti-Communism. For $5 a day—or $20 for the week—participants were treated to a slate of anticommunist films, lectures, and discussions in a packed schedule that ran from 8:30 a.m. to 9:45 p.m. The first School of Anti-Communism was held in St. Louis, but they soon spread to cities around the nation including Los Angeles, New York, Chicago, Houston, Dallas, Miami, San Diego, San Francisco, Seattle, and Portland.

While the school made an impression on the public, it also impacted the finances of the Christian Anti-Communism Crusade. The accounting firm of Ernst & Ernst reported that the organization raked in $311,253 for the week, an impressive sum in light of the low admission fees. Even after expenses, the CACC still turned nearly $250,000 in profits. Schwarz promised the proceeds would be used to operate similar schools across the country. But in the short term, he decided to capitalize on the overwhelming local popularity of the Southern California school of by staging a sequel two months later, billed as “Hollywood’s Answer to Communism.” Organizers worked diligently to surpass the success of the first event. Frawley again led the way, this time securing the landmark Hollywood Bowl for the rally. As master of ceremonies, he enlisted the former song-and-dance man and future US senator George Murphy. The actors made a curtain call as well, with Reagan, Wayne, Boone, Rogers, and Evans all on hand again. This time, though, they were joined by a cast of all-stars that included Jimmy Stewart, Rock Hudson, Robert Stack, Donna Reed, Ozzie and Harriet Nelson, Nat “King” Cole, Jane Russell, Edgar Bergen, Andy Devine, Walter Brennan, Tex Ritter, Irene Dunne, Vincent Price, Cesar Romero, and a host of others then starring on television and in film. Notable directors such as John Ford and studio executives such as Walt Disney and Jack Warner offered their support too.

“When I finally spoke,” Schwarz remembered, “only ten minutes remained, so I delivered an uncharacteristically brief message. It was sufficiently forceful to earn me a comparison to Adolf Hitler in the student newspaper of Stanford University.” The highlight of the Hollywood Bowl event, however, was a special appearance by C. D. Jackson, the publisher of Life magazine. After the Southern California school, his publication ran a two-paragraph item that dismissed the event as a gathering of wild-eyed extremists no different from the John Birch Society. Privately, Schwarz knew well that the two far-right groups often shared a common constituency. In a nine-page, single-spaced letter, Birch Society founder Robert Welch informed him in the fall of 1960 that “we have told our members to encourage, support, and work for your ‘schools’ wherever they were put on, so far as they had the opportunity and ability to do so; and to encourage the attendance of friends and acquaintances (as well as attending themselves).” In some instances, Birchers had taken an even more prominent role in the CACC schools. “I know,” Welch wrote, “that at your recent school in San Diego, some of the people who worked hardest to bring it off successfully were our members, for I saw right on the listing of committees and workers the names of some of our members who had specifically written to ask us whether or not they should participate, and whom we encouraged to do so.” Likewise, “quite a number of the leaders and hardest workers” in the Milwaukee and Chicago schools had been Birchers too.

Publicly Schwarz bristled at any suggestion that his organization had anything in common with the increasingly marginalized Birchers. In retaliation for the hit piece in Life, CACC’s sponsors lashed out. An FBI report noted that Frawley “at once cancelled $80,000 ‘Life’ advertising accounts for Schick Razor and Technicolor.” At the same time, “Richfield and other large national advertisers also withdrew substantial contracts calculated to total half million dollars.” (The sponsors went after less prominent critics with equal zeal. In September 1961, an executive with Richfield Oil sent the head of the Los Angeles FBI office the names and addresses of a dozen private citizens who had written the corporation to complain about its sponsorship of the school, suggesting that they needed to be formally investigated.) Meanwhile, conservative activists organized a grassroots campaign calling for individuals to cancel their subscriptions.

He sat down to write the Engel decision 15 years later, Black was determined to defend the wall of separation between Church and State. Religious liberty was essential, he told his wife, because “when one religion gets predominance, they immediately try to suppress the others.” History was littered with evidence of the dangers that inevitably followed when church and state merged. “People had been tortured, their ears lopped off, and sometimes their tongues cut or their eyes gouged out,” Black continued, “all in the name of religion.” To illustrate that point, the justice crafted a rigorously researched opinion. He began with the Book of Common Prayer and then reread John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, a classic Christian allegory written by a Baptist author who had been imprisoned for defying the Church of England. That was merely the beginning. “The Judge had religious references on his fingertips,” marveled one of his clerks, who ran back and forth to the library to collect them. As he wrote and rewrote the opinion, Black piled on more history each time. Lower courts had repeatedly made unsubstantiated claims about the nation’s “religious heritage” to support the defendants in Engel, but Black was determined to expose their errors with a meticulously researched rebuttal. By the sixth draft, the bulk of his opinion had become a lengthy narrative about the tangled history of church-state relations in the entire Anglo-American world from the 16th to 18th centuries. “It is a matter of history,” he insisted, “that this very practice of establishing governmentally composed prayers for religious services was one of the reasons which caused many of our early colonists to leave England and seek religious freedom in America.” Based on their “bitter personal experience,” Black wrote, the founders crafted the First Amendment to keep the state out of religion and religion out of the state.

In Black’s view, religion certainly deserved a place of prominence in American life, but the state could not dictate it. “It is no part of the business of government,” he read, “to compose official prayers for any group of the American people to recite as a part of a religious program carried on by the government. “The prayer of each man from his soul must be his and his alone,” he said. “If there is anything clear in the First Amendment, it is that the right of the people to pray in their own way is not to be controlled by the election returns.

The outraged reaction to the Engel decision was, in large part, driven by alarmist coverage in the press. The court’s majority had gone to great lengths to note that their ruling merely struck down the Regents’ Prayer and, moreover, did so only because of the unique role that New York State officials played in its composition and implementation, but newspapers lost the nuances. “God Banned from the State,” ran a typically hyperbolic headline. Hostile editorials only compounded the problem. The New York Daily News, for instance, lambasted the “atheistic, agnostic, or what-have-you Supreme Court majority,” while the Los Angeles Times complained they made “a burlesque show” of the First Amendment. Publisher William Randolph Hearst Jr. went so far as to call for a complete rewriting of the First Amendment in a signed editorial that ran in all his papers. The media’s misrepresentations were so widespread that the Columbia Journalism Review devoted its fall issue to figuring out just how and why it had all gone so spectacularly wrong.

For a year and a half, Kennedy managed to avoid issues of church and state. But now the Warren Court had forced his hand. In a press conference two days after the decision, Kennedy finally addressed it. In measured remarks, he cautioned Americans to approach the issue calmly. Noting that it was important to “support the Supreme Court’s decisions even when we may not agree with them,” the president reminded Americans that “we have in this case a very easy remedy, and that is to pray ourselves, and I would think that it would be a welcome reminder to every American family that we can pray a good deal more at home, we can attend our churches with a good deal more fidelity, and we can make the true meaning of prayer much more important in the lives of all our children.” As Kennedy called for calm, however, a few of his predecessors fueled the fires. Herbert Hoover denounced Engel as a “disintegration of a sacred American heritage,” while Eisenhower asserted that he “always thought this nation was an essentially religious one.” Truman pointed out that it was actually the Court’s duty to interpret the Constitution, but he was largely ignored.

Congressional leaders only ramped up their rhetoric. The ruling, Senator Herman Talmadge of Georgia thundered, was “an outrageous edict” and “a blow to all believers in a Supreme Being.” His colleagues in the Senate largely agreed. Barry Goldwater of Arizona denounced the decision as a “blow to our spiritual strength,” while James Eastland of Mississippi likewise called it as a major step toward “the destruction of the religious and spiritual life of this country.

Winegarner’s role in the debate was short-lived. In May 1964, columnists Roland Evans and Robert Novak revealed that the Citizens Congressional Committee was “operated, financed, and directed by Gerald L. K. Smith, notorious promoter of right-wing causes,” and that Winegarner was Smith’s nephew. A onetime ally of Senator Huey Long and an outspoken anti-Semite, Smith had made no secret of his involvement, bragging that the committee was “an auxiliary, financed and directed by The Cross and the Flag,” the far-right publication of his Christian Nationalist Crusade. In its pages, Smith attacked the “cabal of international Jews” in the Kennedy administration and the “nine-man oligarchy” they manipulated on the Supreme Court, before telling readers there was hope. With its “mammoth petition,” the Citizens Congressional Committee had demanded the restoration of “the right of Christian devotions in public schools.

While exposure of the committee’s extremist roots was embarrassing to the larger cause, it was not surprising. Indeed, the campaign for a constitutional amendment to restore prayer to public schools had quickly attracted activists on the far right. Billy James Hargis of the archconservative Christian Crusade devoted himself to circulating petitions across the West, while Carl McIntire, a fundamentalist broadcaster with an affinity for far-right politics, lobbied for it over his own network of 582 radio stations. The John Birch Society supported the amendment idea as part of its long-standing drive to impeach Earl Warren and generally discredit the Supreme Court. Similarly, segregationists who criticized the Court’s rulings on civil rights latched on to the school prayer issue as a more popular and palatable way to condemn it again.

The visibility of such supporters led some to dismiss the constitutional prayer amendment as a cause championed only by the far right or the Deep South, but in truth it had much broader backing. At the 1962 Governors’ Conference, the leaders of forty-nine states called for a prayer amendment that “will make clear and beyond challenge the acknowledgment of our nation and people of their faith in God”; a year later, they renewed their call unanimously. The governors weren’t alone. The Supreme Court’s rulings against school prayer and Bible reading were deeply unpopular across the nation, and a solid majority of Americans seized on the amendment idea as a solution. In August 1963, shortly after the Schempp decision, Gallup asked Americans if they wanted prayer and Bible reading in public schools; 70 percent said yes. They flooded their political representatives with mail, with one study estimating that 50 percent of all correspondence to Congress in the 1963–1964 term focused on the proposal for a school prayer amendment. These letters, postcards, and petitions overwhelmingly supported the idea, with officials citing a margin of nearly twenty to one in favor. Congress leapt into action. Between the summer of 1962 and spring of 1964, 113 representatives and 27 senators introduced 146 different amendments to restore prayer and Bible reading to public schools.5 With such overwhelming popular and political support, the “prayer amendment” seemed sure to sail through Congress and be ratified by the states with equal speed.

Though the two camps in this battle were far from homogeneous, each clustered around a set of convictions. To put it in broad strokes, proponents of the prayer amendment believed America was a Christian nation—or, in their more generous moments, a Judeo-Christian nation. They were deeply invested in promoting a prominent role for religion in public life, believing that formal recognition of God was not simply an affirmation of the nation’s religious roots but an essential measure for preserving the country’s character. In their eyes, liberty came directly from God. If Americans ever came to believe that their rights stemmed from the state instead, then those rights could just as easily be taken away by the state. Thus, the debate for the pro-amendment side was about much more than school prayer; it was about the survival of the nation.

For opponents of the amendment, the stakes were just as high. Legal and religious authorities who opposed the idea warned that a school prayer amendment would radically reshape the status quo, effectively weakening the First Amendment’s guarantee of religious freedom. Under a new “tyranny of the majority,” they believed, local religious minorities would be persecuted. But more than that, all faiths would be endangered. If the state intruded on churches’ and synagogues’ roles as religious educators, it would usurp not just their activities but also their authority. In their place, the state would foster a broader but blander public religion, one drained of the vital details that animated individual faiths. The prayer amendment, the heads of major denominations concluded, would ultimately hurt religion rather than help it.

While Celler’s delaying tactics enraged supporters of the Becker Amendment, they proved crucial in giving opponents time to mobilize. Most civil libertarians and religious organizations had assumed the campaign for a constitutional amendment would go nowhere, but as momentum shifted in Becker’s direction they realized, almost too late, what was happening. In March, ACLU headquarters sent its affiliates warnings that the discharge petition drive was “becoming alarming.” They scrambled to find allies. The Baptist Joint Committee on Public Affairs, the political voice of the eight largest Baptist bodies in the nation, soon announced its opposition, claiming the Becker Amendment threatened their religious liberty. A week later, the American Jewish Committee denounced it as “the most serious challenge to the integrity of the Bill of Rights in American history.” On St. Patrick’s Day, representatives of Protestant and Jewish organizations and civil liberties groups gathered at a hastily arranged meeting in New York. Sizing up the situation, they realized the Becker Amendment had “an excellent chance” of winning a majority of votes from the Judiciary Committee. If that happened, the full House and Senate would invariably vote for it.

Reverend Eugene Carson Blake of the United Presbyterian Church worried that “school prayer and Bible reading either become a ritual that is meaningless and has no effect on the children, or it is some kind of indoctrination.” Either way, it amounted to “state religion,” he warned. “If you get the idea that religion and Americanism are the same thing, all of us are scared to death, because we think religion transcends the State.

“The politician who says he believes in reducing the scope of Government and then asks for a Government role in nurturing and guiding the inner man can expect scrutinizing conversations as these issues are pursued by our people in future debate.

“It is so easy to think that one is voting for prayer and the Bible,” cautioned the Christian Science Monitor. “It comes as a shock that this is not the issue. The issue is that agencies of government cannot avoid favoring one denomination and hurting another by the practical decisions that have to be made by government authority on what version of the Bible shall be imposed and what prayer. The churches know this and that is why they are against the Becker Amendment.

The prolonged fight over the amendment marked not the end of a struggle but the beginning. The House hearings revealed how fault lines across the country were shifting on the issue of separation of church and state. Clerical leaders had taken stands that were largely in line with their denominations’ traditional perspectives on the matter, but conservative laymen recoiled from their arguments. They felt bewildered—and, in many instances, betrayed—by their leaders’ objections to seemingly wholesome traditions such as school prayer and Bible reading. Their faiths’ traditional stances on issues of church-state separation had always seemed academic. In the wake of Becker’s failure, conservative laymen began to doubt the authority of their religious representatives and look for new leaders to replace them.

Dirksen refused to accept defeat. “This crusade will continue,” he announced. “The next time, we will be better organized throughout the country.” In a telephone call the night before the vote, he had been assured by Dr. Daniel Poling, the eighty-one-year-old fundamentalist and former editor of the Christian Herald, that a new grassroots organization would rise up to champion the cause of school prayer. Its leaders would be Poling, Billy Graham, and a “Catholic prelate” to be named later. That specific organization never came to pass, but the proposal was prescient. For too long, religious conservatives believed that their voice in political matters—especially when it came to the role of religion in public life—had been drowned out by the more liberal leaders of their denominations. If conservative Christians at the grassroots would simply organize themselves according to their politics rather than their particular denominations, they could end the reign of the religious establishment. If effective leaders could bridge the long-standing gaps between different faiths—and bring together, as Poling proposed, conservative Catholics with fundamentalist and evangelical Protestants—then laypeople would finally have their say.

When he tried to explain his razor-thin loss in the 1960 presidential race, Nixon often singled out a last-minute decision by Life publisher Henry Luce to scrap an article in which Graham had given him a strong endorsement. Both Nixon and Graham believed the article would have made the difference.