Pesticides, herbicides, and insecticides destroy soil and ecosystems. Yet a third of crops are lost to pests just as in the many millennia of farming before chemicals

Preface. This is a book review of Dyer’s “Chasing the Red Queen”, and I have added additional information and conclusions. This book is not technical and could be read by both high school and undergraduate students as an introduction to soil ecosystems and the damage done by agricultural chemicals, and the science of why this is ultimately not sustainable.

Preface. This is a book review of Dyer’s “Chasing the Red Queen”, and I have added additional information and conclusions. This book is not technical and could be read by both high school and undergraduate students as an introduction to soil ecosystems and the damage done by agricultural chemicals, and the science of why this is ultimately not sustainable.

And here’s a new wrinkle, pesticides can increase the number of mosquitoes: Mosquitoes … have evolved resistance to chemicals meant to kill them. The mosquitoes’ predators, meanwhile, have not kept pace with that evolution—and that has allowed the mosquito population to boom. Resistance to the major groups of insecticides is widespread around the world, and especially worrying that mosquitoes are unaffected, since they spread many dangerous diseases (Weathered 2019).

Pesticides in the news:

- In 2020 the U.S. House introduced the “Protect America’s Children from Toxic Pesticides Act” because every year the U.S. uses over a billion pounds of pesticides — nearly a fifth of worldwide use. Once approved pesticides often stay on the market for decades, even when scientific evidence overwhelmingly shows a pesticide is causing harm to people or the environment. In 2017 and 2018, the Environmental Protection Agency registered more than 100 pesticides containing ingredients widely considered to be dangerous. Approximately one-third of annual U.S. pesticide use — over 300 million pounds from 85 different pesticides — comes from pesticides that are banned in the European Union. The pesticide regulation statute, the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide and Rodenticide Act of 1972 (“FIFRA”), contains many loopholes that put the interests of the pesticide industry above the health and safety of people and our environment.

- A third of the planet’s agricultural land is at “high risk” of pesticide pollution, and 64% at risk from the lingering residue of chemical ingredients that can leach into water supplies and threaten biodiversity (MacNamara 2021, Tang 2021).

- Vital soil organisms being harmed by pesticides. The tiny creatures are the ‘unsung heroes’ that keep soils healthy and underpin all life on land. Soil organisms are rarely considered when assessing the environmental impact of pesticides. The US, for example, only tests chemicals on honey bees, which may never come into contact with soil (Carrington 2021, Gunstone et al 2021).

- An ethanol plant that uses pesticide treated corn seed is killing bees, and poisoning animals, land, and waterways (Gillam 2021).

- In California’s Farm Country, Climate Change Is Likely to Trigger More Pesticide Use, Fouling Waterways. Warmer temperatures would boost pest populations, causing farmers to use more insecticides that, with more frequent and severe storms, turn into toxic runoff (Gross 2021).

- Ancestral exposure to environmental chemicals, banned decades ago, may influence the development of earlier menarche and obesity for several generations, and these chemicals are risk factors for breast cancer and cardiometabolic diseases (Cirillo et al 2021).

- A good history of why we aren’t protected from pesticides in this article. “As infuriating as the Trump administration’s favoritism toward the pesticide industry may be, it’s nothing new. Since the dawn of the pesticide era during World War II, federal regulators in administrations from both major parties have adopted lax, pro-industry standards that have allowed potentially dangerous pesticides to remain legal” (Conis 2019).

- Pesticides are INCREASING the number of mosquitoes by killing off their predators, while mosquitoes develop resistance (Buehler 2019)

Alice Friedemann www.energyskeptic.com Author of Life After Fossil Fuels: A Reality Check on Alternative Energy; When Trucks Stop Running: Energy and the Future of Transportation”, Barriers to Making Algal Biofuels, & “Crunch! Whole Grain Artisan Chips and Crackers”. Women in ecology Podcasts: WGBH, Jore, Planet: Critical, Crazy Town, Collapse Chronicles, Derrick Jensen, Practical Prepping, Kunstler 253 &278, Peak Prosperity, Index of best energyskeptic posts

***

Dyer, A. 2014. Chasing the Red Queen. The evolutionary race between Agricultural pests and poisons. Island Press.

We hear a lot about how we’re running out of antibiotics. But we are also doomed to run out of pesticides, because insects inevitably develop resistance, whether toxic chemicals are sprayed directly or genetically engineered into the plants.

Worse yet, weeds, insects, and fungus develop resistance in just 5 years on average, which has caused the chemicals to grow increasingly lethal over the past 60 years. And it takes on average 8 to 11 years to identify, test, and develop a new pesticide, though that isn’t long enough to discover the long-term toxicity to humans and other organisms. And few make the cut: pesticides go through extensive studies and only one in 10,000 discoveries make the 11-year journey from the lab to the market (AP 2021).

Or maybe we’ll kill ourselves first. The U.S. applied 1.2 billion pounds of pesticide in 2016, and 322 million of these pounds were banned in the EU, 40 million pounds banned in China and 26 million pounds banned in Brazil (Donley 2019).

And this devil’s bargain hasn’t even provided most of the gains in crop yields, which is due to natural-gas and phosphate fertilizers plus soil-crushing tractors and harvesters that can do the work of millions of men and horses quickly on farms that grow only one crop on thousands of acres.

Yet before pesticides, farmers lost a third of their crops to pests, after pesticides, farmers still lose a third of their crops.

Even without pesticides, industrial agriculture is doomed to fail from extremely high rates of soil erosion and soil compaction at rates that far exceed losses in the past, since soil couldn’t wash or blow away as easily on small farms that grew many crops.

But pest killing chemicals are surely accelerating the day of reckoning sooner rather than later. Enormous amounts of toxic chemicals are dumped on land every year — over 1 billion pounds are used in the United State (US) every year (Alavanja 2009) and 7.7 billion pounds globally of this $45 billion market (Givetash 2019).

This destroys the very ecosystems that used to help plants fight off pests, and is a major factor biodiversity loss and extinction.

Evidence also points to pesticides playing a key role in the loss of bees and their pollination services. Although paleo-diet fanatics won’t mind eating mostly meat when fruit, vegetable, and nut crops are gone, they will not be so happy about having to eat more carbohydrates. Wheat and other grains will still be around, since they are wind-pollinated.

Agricultural chemicals render land lifeless and toxic to beneficial creatures, also killing the food chain above — fish, amphibians, birds, and humans (from cancer, chronic disease, and suicide).

Surely a day is coming when pesticides stop working, resulting in massive famines. But who is there to speak for the grandchildren? And those that do speak for them are mowed down by the logic of libertarian capitalism, which only cares about profits today. Given that a political party is now in power in the U.S. that wants to get rid of the protections the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and other agencies provide, may make matters worse if agricultural chemicals are allowed to be more toxic, long-lasting, and released earlier, before being fully tested for health effects.

Meanwhile chemical and genetic engineering companies are making a fortune, because the farmers have to pay full price, since the pests develop resistance long before a product is old enough to be made generically.

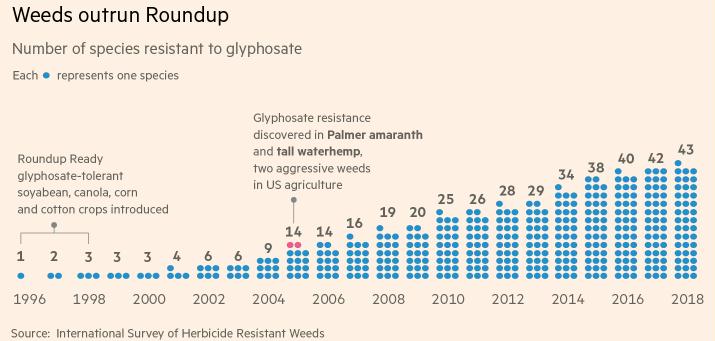

Glyphosate was seen as a miracle chemical in destroying weeds, but look at how fast weeds developed resistance. Predictably.

A single Palmer amaranth weed can grow three inches a day and sprout 1m seeds atop a stem thick as a forearm. Originally from the desert south-west, its range will push into Canada and Europe as temperatures rise due to climate change, according to research from Erica Kistner and Jerry Hatfield of the US Department of Agriculture.

Some weeds have built defenses against multiple herbicides, making them even harder to manage. In one central Illinois field, researchers found a pigweed species resistant to five different classes of herbicide, one of which had never been used there, said Aaron Hager, professor in the University of Illinois’s crop sciences department. “If your solution to resistance is to open up a new jug, we’re rapidly running out of jugs,” said Prof Hager (Meyer 2019).

In fact, the inevitability of resistance has been known for nearly seven decades. In 1951, as the world began using synthetic chemicals, Dr. Reginald Painter at Kansas State University published “Insect Resistance in Crop Plants”. He made a case that it would be better to understand how a crop plant fought off insects, since it was inevitable that insects would develop genetic or behavioral resistance. At best, chemicals might be used as an emergency control measure.

Farmers will say that we simply must carry on like this, there’s no other choice. But that’s simply not true.

Consider the corn rootworm, that costs farmers about $2 billion a year in lost crops despite spending hundreds of millions on chemicals and the hundreds of millions of dollars chemical companies spend developing new chemicals.

To lower the chances of corn pests developing resistance, corn crops were rotated with soybeans. Predictably, a few mutated to eat soybeans plus changed their behavior. They used to only lay eggs on nearby corn plants, now they disperse to lay eggs on soybean crops as well. Worse yet, corn is more profitable than soy and many farmers began growing continuous corn. Already the corn rootworm is developing resistance to the latest and greatest chemicals.

But the corn rootworm is not causing devastation in Europe, because farms are smaller and most farmers rotate not just soy, but wheat, alfalfa, sorghum and oats with corn (Nordhaus 2017).

Before planting, farmers try to get rid of pests that survived the winter and apply fumigants to kill fungi and nematodes, and pre-emergent chemicals to reduce weed seeds from emerging. Even farmers practicing no-till farming douse the land with herbicides by using GMO herbicide-resistant crops. Then over the course of crop growth, farmers may apply several rounds of additional pesticides to control different pests. For example, cotton growers apply chemicals from 12 to 30 times before harvest.

Currently, the potential harm is only assessed for 2 to 3 years before a permit is issued, even though the damage might occur up to 20 years later.

Although these chemicals appear to be just like antibiotics, that isn’t entirely true. We develop some immunity to a disease after antibiotics help us recover, but a plant is still vulnerable to the pests and weeds with the genetics or behavior to survive and chemical assault.

Although there are thousands of chemical toxins, what matters is how they kill, their method of action (MOA). For herbicides there are only 29 MOAs, for insecticides, just 28. So if a pest develops resistance to one chemical within an MOA, it will be resistant to all of the thousands of chemicals within that MOA.

Since 1984, there have been no new ways to kill weeds with herbicides (Charles 2019).

The demand for chemicals has also grown due the high level of bioinvasive species. It takes a while to find native pests and make sure they won’t do more harm than good. In the 1950s there were just three main corn pests. By 1978 there were 40, and they vary regionally. For example, California has 30 arthropods and over 14 fungal diseases to cope with.

When I was learning how to grow food organically back in the 90s, I remember how outraged organic farmers were that Monsanto was going to genetically engineer plants to have the Bt bacteria in them. This is because the only insecticide organic farmers can use is Bt bacteria, because it is found in the soil. It’s natural. Organic farmers have been careful to spray only in emergencies so that insects didn’t develop resistance to their only remedy. Since 1996, GMO plants have been engineered to have Bt in them, and predictably, insects have developed resistance. For example, in 2015, 81% of all corn was planted with genetically engineered Bt. But corn earworms have developed resistance, especially in North Carolina and Georgia, setting the stage for damage across the nation. Five other insects have developed resistance to Bt as well.

GMO plants were also going to reduce pesticide use. They did for a while, but not for long. Chemical use has increased 7% to 202,000 tons a year in the past 10 years.

Resistance can come in other ways than mutations. Behavior can change. Cockroach bait is laced with glucose, so cockroaches that developed glucose-aversion now no longer take the bait.

It is worth repeating that chemicals and other practices are ruining the long-term viability of agriculture. Here is how author Dyer explains it:

“Ultimately the practice of modern farming is not sustainable” because “the damage to the soil and natural ecosystems is so great that farming becomes dependent not on the land but on the artificial inputs into the process, such as fertilizers and pesticides. In many ways, our battle against the diverse array of pest species is a battle against the health of the system itself. As we kill pest species, we also kill related species that may be beneficial. We kill predators that could assist our efforts. We reduce the ecosystem’s ability to recover due to reduced diversity, and we interfere with the organisms that affect the biogeochemical processes that maintain the soils in which the plants grow.

Soil is a complex, multifaceted living thing that is far more than the sum of the sand, silt, clay, fungi, microbes, nematodes, and other invertebrates. All biotic components interact as an ecosystem within the soil and at the surface, and in relation to the larger components such as herbivores that move across the land. Organisms grow and dig through the soil, aerate it, reorganize it, and add and subtract organic material. Mature soil is structured and layered and, very importantly, it remains in place. Plowing of the soil turns everything upside down. What was hidden from light is exposed. What was kept at a constant temperature is now varying with the day and night and seasons. What cannot tolerate drying conditions at the surface is likely killed. And very sensitive and delicate structures within the soil are disrupted and destroyed.

Conventional tillage disrupts the entire soil ecosystem. Tractors and farm equipment are large and heavy; they compact the soil, which removes air space and water-holding capacity. Wind and water erosion remove the smallest soil particles, which typically hold most of the micronutrients needed by plants. Synthetic fertilizers are added to supplement the loss of oil nutrients but often are relatively toxic to many soil organisms. And chemicals such as pre-emergents, fumigants, herbicides, insecticides, acaricides, fungicides, and defoliants eventually kill all but the most tolerant or resistant soil organisms. It does not take long to reduce a native, living, dynamic soil to a relatively lifeless collection of inorganic particles with little of the natural structure and function of undisturbed soil”.

My take on how we got here and why it’s so hard to do something

When I told my husband all the reasons we use agricultural chemicals and the harm done, my husband got angry and said “Farmers aren’t stupid, that can’t be right!”

I think there are a number of reasons why farmers don’t go back to sustainable organic farming.

First, there is far too much money to be made in the chemical herbicide, pesticide, and insecticide industry to stop this juggernaut. After reading Lessig’s book “Republic, Lost”, one of the best, if not the best book on campaign finance reform, I despair of campaign financing ever happening. So chemical lobbyists will continue to donate enough money to politicians to maintain the status quo. Plus the chemical industry has infiltrated regulatory agencies via the revolving door for decades and is now in a position to assassinate the EPA, with newly appointed Scott Pruitt, who would like to get rid of the EPA.

Second, about half of farmers are hired guns. They don’t own the land and care about passing it on in good health to their children. They rent the land, and their goal, and the owner’s goal is for them to make as much profit as possible.

Third, renters and farmers both would lose money, maybe go out of business in the years it would take to convert an industrial monoculture farm to multiple crops rotated, or an organic farm.

Fourth, it takes time to learn to farm organically properly. So even if the farmer survives financially, mistakes will be made. Hopefully made up for by the higher price of organic food, but as wealth grows increasingly more unevenly distributed, and the risk of another economic crash grows (not to mention lack of reforms, being in more debt now than 2008, etc).

Fifth, industrial farming is what is taught at most universities. There are only a handful of universities that offer programs in organic agriculture.

Sixth, subsidies favor large farmers, who are also the only farmers who have the money to profit from economies of scale, and buy their own giant tractors to farm a thousand acres of monoculture crops. Industrial farming has driven 5 million farmers off the land who couldn’t compete with the profits made by larger farms in the area.

But farmers will have to go organic whether they like it or not as energy declines (agriculture uses 15-20% of fossil fuel energy in the U.S.) and petroleum based pesticides, herbicides, insecticides and fungicides can no longer be made. And as natural gas declines, the artificial fertilizers made out of natural gas that allow 4+ billion of us to be alive will have to be replaced with compost from plants and manure.

Wouldn’t it be easier to start the transition now?

What to do

We already know what to do. There are hundreds, if not thousands of books and journal articles on how to convert an industrial farm to an organic one, such as:

- Use pesticides less often, and only when absolutely necessary with integrated pest management guidelines to slow resistance down from 5 years to 8 years

- Stop monoculture, or rotating just two crops, because insects can develop resistance.

- Surround farms with wild land to increase biodiversity and provide more niches for birds, insects, and other natural predators of crop pests.

- Restore the natural fertility of soil with manure, crop resides, compost, and cover crops.

- Improve crop biodiversity and pest resistance by growing more varieties of corn, wheat, potatoes

- Educate farmers like Ray Archuleta at the natural resources conservation service. He’s been teaching classes on how to restore soils in as little as two to three years.

- Before fossil fuels, 90% of the population were farmers. Provide meaningful jobs by breaking up large farms into smaller ones that grow many crops

And for some pests, like the green aphid, which has grown so resistant to so many chemicals that farmers are running out of options, a healthy ecosystem approach may be the only thing left to try.

The European Union has initiated an ambitious plan called Farm to Fork (EU 2021) that hopes to cut pesticide and excess nutrient use by 50%, and converting 25% of farms to organic agriculture by 2030 (Rosmino 2021).

And there are farms that grow insects to replace pesticides. We need to subsidize more of them, add programs to agricultural colleges in studying the best ways to breed them and find new insects (Katanich 2021).

Related links

October 20, 2017 Insectageddon: farming is more catastrophic than climate breakdown. The shocking collapse of insect populations hints at a global ecological meltdown by George Monbiot, the Guardian

References

Alavanja, M. 2009. Pesticides Use and Exposure Extensive Worldwide. Rev Environmental Health.

AP (2021) Toxic tradeoff: U.S. pesticide use falls but harms pollinators more, study finds. Associated Press.

Benbrook, C. M. 2015. Trends in glyphosate herbicide use in the United States and globally. Environmental sciences Europe.

Buehler J (2019) How pesticides can actually increase mosquito numbers The blood suckers evolve resistance, but their predators don’t. National Geographic

Carrington D (2021) Vital soil organisms being harmed by pesticides, study shows. The Guardian.

Charles, D. 2019. As Weeds Outsmart The Latest Weedkillers, Farmers Are Running Out Of Easy Options. NPR.

Cirillo PM et al (2021) Grandmaternal Perinatal Serum DDT in Relation to Granddaughter Early Menarche and Adult Obesity: Three Generations in the Child Health and Development Studies Cohort. Cancer Epidemiology, biomarkers, and prevention.

Conis E (2019) Why both major political parties have failed to curb dangerous pesticides. Washington Post.

Donley, N. 2019. USA lags behind other agricultural nations in banning harmful pesticides. Environmental Health.

EU (2021) Farm to Fork Strategy. European Commission.

Gillam C (2021) There’s a red flag here’: how an ethanol plant is dangerously polluting a US village. Situation in Mead, Nebraska, where AltEn has been processing seed coated with fungicides and insecticides, is a warning sign, experts say. The Guardian.

Givetash, L. 2019. Mideast farmers who use pesticides often find no buyers abroad. CBS news.

Gross L (2021) In California’s Farm Country, Climate Change Is Likely to Trigger More Pesticide Use, Fouling Waterways. Insideclimatenews.org

Gunstone et al (2021) Pesticides and Soil Invertebrates: A Hazard Assessment. Front. Environ. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2021.643847

Katanich D (2021) This farm is breeding insects to replace pesticides. Euronews.

MacNamara K (2021) A third of global farmland at ‘high’ pesticide pollution risk. Phys.org

Meyer, G. 2019. Super weeds blight Bayer’s hopes for Monsanto. Financial Times.

Nordhaus, H. March 2017. Cornboy vs. the billion-dollar bug. Technology to defeat the corn rootworm, scientists worry, will work only briefly against an inventive foe. Scientific American.

Rosmino C (2021) Meet the EU farmers using fewer pesticides to make agriculture greener. Euronews.com.

Tang FHM et al (2021) Risk of pesticide pollution at the global scale. Nature Geoscience 14: 206-210.

Weathered, J., et al. 2019. Adaptation to agricultural pesticides may allow mosquitoes to avoid predators and colonize novel ecosystems. Oecolgia 190: 219-227.