Preface. This is a book review of Sterba’s “Nature Wars” and our interaction with wildlife as our insanely huge population growth wipes out nature.

A few excerpts about this from the book:

“…In New England woodlots supplied fuel to households, each of which consumed 10 to 30 cords of wood per winter to heat a drafty house with an inefficient fireplace or stove.

The Fitchburg Railroad line ran along the south side of Walden Pond, and its locomotives burned wood for fuel. By 1854 forests in the area had been cut down to almost their low point, more deforested than at any time before or since. In 1910, more than 350,000 miles of rail lines had been built-up from only 10,000 miles in 1850. Crossties wore out and had to be replaced on 50,000 miles of track annually, which meant cutting down 5 to 20 million acres of trees a year.

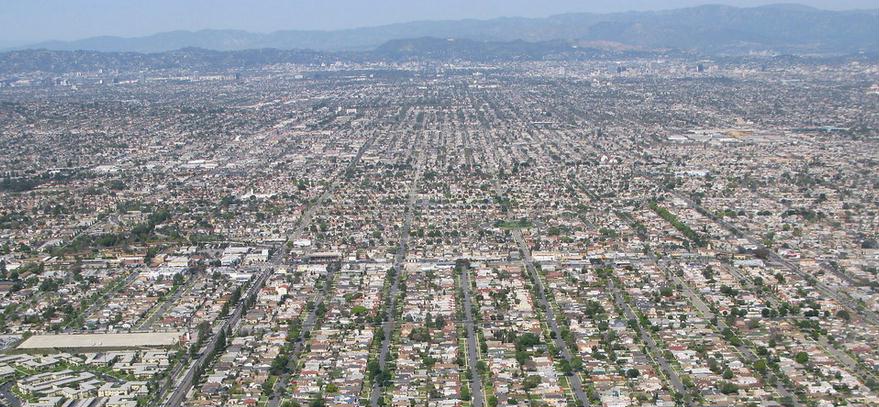

The 2000 Census had revealed that for the first time an absolute majority of the American people lived not in cities, not on farms, but in an ever- expanding suburban and exurban sprawl in between. Never in history have so many people lived this way. In historical terms, sprawl blossomed overnight.

Cars began running over animals as soon as the first ones were invented in nineteenth-century Europe. By 1900, more than 400 companies in the United States, most tiny and many one- or two-man operations, were building automobiles, mainly by hand. The founders of the conservation movement couldn’t have imagined how this machine would alter the landscape. When Theodore Roosevelt became president in 1901, automobiles were few, roads were slow-going, and suburbs were tiny bastions of the cosseted elite. Fast was thirty miles an hour. Today, 15 million acres of road surface and 12 million acres of roadside cover the U.S., for a total of 27 million acres—excluding 2.8 million acres of parking lots.

“Humans have spread an enormous net over the land. As the largest human artifact on earth, this vast, nearly five-million-mile road network used by a quarter billion vehicles permeates virtually every corner of North America,” wrote Richard T. T. Forman in the preface to Road Ecology. “Roads and vehicles are at the core of today’s economy and society.” Melvin Webber, another author, described this net as “an efficient personal and commercial network connecting everywhere to everywhere.” By 2003, the U.S. road network was 3,997,456 miles long, and roughly two-thirds of it was surfaced either with asphalt (95%) or concrete (5%). In 2007, Americans were driving 254.4 million motor vehicles 3 trillion miles—double the number just a decade earlier.”

Since my books, “Life After Fossil Fuels: A Reality Check on Alternative Energy; When Trucks Stop Running: Energy and the Future of Transportation”, explain why we will be going back to the 14th century and 80-90% of us become farmers, this was of note too:

“Hands-on farm families still made up 38% of the American population in 1900. It is also difficult today to imagine how harsh farm life was. Kids were an important source of farm labor. Among their chores was gathering kindling for the kitchen stove, pulling weeds, picking vegetables, shocking sheaves of oats and corn, putting up hay, and killing farm animals.

Every drop of water we used for drinking, making coffee, cooking, washing our faces and hands in a tiny washbowl, washing dishes in a small basin, and taking baths in a galvanized tub (usually once a week whether we needed it or not) had to be hand-pumped and carried in buckets from a well across the road—a distance of fifty yards. I got a lot of experience carrying water, priming the stubborn pump, carrying boiling water to it in the winter to thaw it out before it could be primed, carrying water over ice and through snow. None of it was fun. But doing it taught me not to waste water and to think ahead about the season and weather and what would be required to fetch water.

Our outhouse sat on the side of a hill just beyond our garden, about thirty yards from the house. As the joke goes, in the winter it was thirty yards too far and in the summer it was thirty yards too near. The smell of human and livestock waste was part of farm life.”

This sprawling book covers a lot of ground about our sprawl and the wide-ranging effects. Below are my kindle notes, which leave quite a bit of important material out, since I’m focused on the energy and limits to growth writing above all — so do get this important and entertaining book!

Alice Friedemann www.energyskeptic.com Author of Life After Fossil Fuels: A Reality Check on Alternative Energy; When Trucks Stop Running: Energy and the Future of Transportation”, Barriers to Making Algal Biofuels, & “Crunch! Whole Grain Artisan Chips and Crackers”. Women in ecology Podcasts: WGBH, Jore, Planet: Critical, Crazy Town, Collapse Chronicles, Derrick Jensen, Practical Prepping, Kunstler 253 &278, Peak Prosperity, Index of best energyskeptic posts

***

Sterba, J. 2012. Nature Wars: The Incredible Story of How Wildlife Comebacks Turned Backyards into Battlegrounds. Random house.

Massachusetts has an estimated 3,500 bears. Healthy bear populations in New Hampshire, Vermont, Pennsylvania, and New York have spread south into New Jersey, which is now home to perhaps four thousand bruins, along with lots of political and legal battles over hunting them.

Although moose were almost wiped out of Maine by 1935, the state’s moose population is now estimated at 29,000, and New Hampshire, Vermont, and New York have plenty, too. Massachusetts has nearly one thousand, and moose-vehicle crashes are mounting in the region, with often fatal consequences for both moose and driver. Moose are solitary creatures but are increasingly wandering into towns and suburbs from Boston to Burlington, where a recent headline in the Free Press read: “Urban Moose Here to Stay.” Moose began infiltrating Connecticut in the 1990s, and more than one hundred now roam the state, which wildlife biologists believe is the southernmost extent of their range.

It is very likely that more people live in closer proximity to more wild animals and birds in the eastern United States today than anywhere on the planet at any time in history. This region’s combination of wild animals, birds, and people is unique in time and place, the result of a vast but largely unnoticed regrowth of forests, the return of wildlife to the land, and the movement of people deeper into the exurban countryside. People now share the landscape with millions of deer, geese, wild turkeys, coyotes, and beavers; thousands of bears, moose, and raptors; formerly domesticated feral pigs and cats; and uncountable numbers of small wild animals and birds.

Before Columbus arrived, for example, several million Native Americans and perhaps 30 million white-tailed deer lived in the eastern forests-the heart of the whitetail’s historic range in North America. Today in the same region there are more than 200 million people and 30 million deer, if not more. I have seen neighborhoods so fenced to keep out deer that their residents joke of living in prisoner-of-war camps.

People have very different ideas regarding what to do, if anything, about the wild creatures in their midst, even when they are causing problems. Enjoy them? Adjust to them? Move them? Remove them? Relations between people and wildlife have never been more confused, complicated, or conflicted. One reason for confusion and conflict is that Americans have become denatured. That is to say, they have forgotten the skills their ancestors acquired to manage an often unruly natural world around them, and they have largely withdrawn from direct contact with that world by spending most of their time indoors, substituting a great deal of real nature with reel nature-edited, packaged, digitized, and piped in electronically. The arts of animal husbandry and farming were forgotten by most modern Americans, as were the woodsman skills of logging, stalking, hunting, and trapping. American communities are full of what writer Paul Theroux calls “single species obsessives.” I call them species partisans-people who choose a particular group or flock, or even individual animals, to defend. Each species has a constituency, be they geese, deer, bears, turkeys, beavers, coyotes, cats, or endangered plovers. Many people, of course, want to save all species.

When coyote sightings in Wheaton, Illinois, increased dramatically, and a resident’s dog was mauled by a coyote and had to be euthanized, the town divided into pro-coyote and anti-coyote factions. A nuisance wildlife professional, hired by the city council, discovered that a few residents were feeding the coyotes. He trapped and shot four of the animals, then began receiving voice-mail death threats. A brick was tossed through a city official’s window, and council members received threatening letters. The FBI was called in.

Feeding wild animals is frowned upon by wildlife professionals. Ironically, doing so and thinking of them as pets stemmed, in part, from the pet industry itself. No one encouraged anthropomorphizing more than the purveyors of pets and products for pets. Since the 1980s, this multi-billion-dollar industry has burgeoned by encouraging people to see pets as companion animals, members of the family, and surrogate offspring; and reinforcing this pretense by creating a range of goods and services that mimic child care: toys and treats, sweaters and booties, pet sitters and day care, pet stress and mood medications, human-grade food, health insurance, and pricey veterinary care.

For people who love pets or treat them like children, it doesn’t take much persuasion to think of wild birds as “outdoor pets,” as one seed company calls them, and to keep feeders full for them. Feeding wild birds is fun and an easy way to connect to wildlife, and its popularity created another multi-billion-dollar industry. Feeding other wildlife is, by extension, a small step.

If a chickadee is an outdoor pet, why isn’t a raccoon or a groundhog? Don’t they warrant a cookie now and then? How about a little dog food for the coyote? Wouldn’t the bear rifling the garbage can prefer a jelly doughnut? Nuisance wildlife control operators know that putting out food for animals, say birds or stray cats, is asking for trouble from others, say raccoons and skunks-and fueling the growth of a sizable new wildlife mitigation industry.

But many people don’t make the connection, until it is too late and a professional has to be summoned. More than one thousand nuisance wildlife companies, and perhaps five thousand part-time operators, have sprung up since the 1980s. Critter Control Inc., for example, began franchising in 1987 and now has more than 130 operations

Feeding wild creatures, whether this is done consciously or unconsciously, is one of the key reasons why many animals have done a far better job of accommodating to life among people than vice versa. While it is fashionable to say that most conflicts between people and wildlife are the result of human encroachment into wildlife habitat, make no mistake, critters have encroached right back. They have discovered that people maintain lush lawns; plant trees, shrubbery, and gardens; create ponds; put up bird feeders and “No Hunting” signs; and put out grills and garbage cans. These places offer up plenty of food, lots of places to hide and raise families, and protection from predators with guns.

Wildlife biologists call this enhanced habitat, meaning that for lots of species it has more and better amenities than can be found in the backwoods away from people. Where do most people in the United States live? The answer is just as counterintuitive: They live in the woods. We are essentially forest dwellers. Sure, tens of millions of people demonstrably don’t live in a forest, and far more of them would not call where they do live a forest. Sure, they have trees in their yard or their neighborhood, or out in back of their house, or along their road or street, or around their cul-de-sac, or in back of the mall. But that isn’t a “forest” forest.

Nevertheless, if you draw a line around the largest forested region in the contiguous United States-the one that stretches from the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Plains-you will have drawn a line around nearly two-thirds of America’s forests (excluding Alaska’s) and two-thirds of the U.S. population. The modern American forest is a very unusual place, and forest dwellers of the past would find the ways we live in it to be bizarre. It is laced with roads and highways, power lines and drainage systems. It is splotched with parking lots, housing developments, office parks, golf courses, and shopping malls, and more of it is being chopped up every year. It covers or surrounds some of the most densely populated regions of America.

The trees seem too obvious not to see, but amid this man-made jumble they can be overlooked, the regrowth of forests on such a scale had not been seen in the Americas since the collapse of the Mayan civilization 1,200 years ago, when millions of acres of once-cultivated land in Central America were left to the jungle. In the eastern United States over two and a half centuries, European settlers cleared away more than 250 million acres of forest. By the 1950s, depending on the region, nearly half to more than two-thirds of the landscape was reforested, and in the last half century, states in the Northeast and Midwest have added more than 11 million acres of forest. Small patches of the island were saved more or less in their natural state. Today what visitors see is a North Woods forest.

What they are looking at, however, is natural beauty re-created, protected, and managed by man-a kind of “wilderness” theme park rebuilt by nature under human supervision. Newcomers like me had difficulty believing that in 1880 this island was a pastoral countryside of hay meadows, livestock pastures and cropland, trees here and there, and forest hugging the steep sides of mountains off in the distance. It was hard to imagine bustling hubs where the commerce of logging, fishing, shipbuilding, and milling had taken place; villages with blacksmiths, shoemakers, wool carders, shingle makers, sawyers, and carpenters; the storefronts of merchants; factories producing lumber, barrels, ice, bricks, stones, and salted fish for market; and wharves where ships loaded materials for export and unloaded goods from afar. But that’s what Mount Desert looked like after the Civil War and well into the twentieth century.

Europeans broke ground on Mount Desert in 1613, when the first settlers-forty-eight Frenchmen led by a Jesuit priest named Father Pierre Biard-arrived at Fernald Point and decided, among other survival tasks, to try a little farming. Long before their crops could come in, however, they were discovered, captured, and driven off by an English privateer based in Virginia named Captain Samuel Argall. His job was to expel all Frenchmen he found along the coast.

In many ways, Mount Desert is a microcosm of what happened on much of America’s original forested landscape-the vast region stretching from the Atlantic coast to the Great Plains that settlers called “wilderness.

That year in Virginia, Captain Argall kidnapped Pocahontas, the seventeen-year-old daughter of the Potomac chief, Powhatan, to exchange for English captives, property, and food. Six years earlier Pocahontas had “rescued” Captain John Smith, leader of the Jamestown Colony, from her father.

Great Eastern Forest. When the first European settlers arrived, three-quarters of all the forests in what would become the continental United States were in the eastern third of the country, mostly east of the Mississippi River.

It was not a continuous blanket of old trees, a so-called climax forest. It was a giant patchwork of ancient stands, young thickets, swamps, and meadows undergoing continual change over centuries. Nature assaulted it with lightning fires, tornados, hurricanes, insects, floods, and droughts. By some accounts, Indians regularly burned untold millions of acres to clear away forest understory of brush, fight insects, or create sight lines for defense and to grow wild berries. They essentially farmed the forest to encourage productive mast (nut) species such as oaks, hickories, and chestnuts, and to enhance habitat to attract the wild animals and birds they depended upon for food, clothing, and tools. Scholars debate how much Indian manipulation occurred and where. Indian populations varied in time and place, but were relatively small in relation to the vast expanses of landscape.

Just how much forest covered what is now the United States before the Europeans arrived isn’t known. Why? Because there was too much of it to measure. The federal government commissioned studies and surveys in the nineteenth century, but it didn’t even take an educated guess at how much forest there was until the twentieth century, after so much lumber had been cut that the nation appeared to be running out of trees.

The first official estimate of forest cover prior to the settlement by Europeans was published in 1909, by Royal S. Kellogg, an assistant to Gifford Pinchot, the head of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Forest Service. It was titled The Timber Supply of the United States. Kellogg assembled what historic land-clearing data he could find, surveyed how much forest was left in 1907, and estimated, state by state, how much forest had probably existed in the year 1630. Kellogg used 1630 to mark the “original forests” before Europeans began cutting them down.

The eastern forest stretched solidly in the north from Maine through Michigan, Wisconsin, and northern Minnesota. It skirted northern Illinois but blanketed middle states and the southern tier west through most of Missouri, eastern Oklahoma, and the eastern half of Texas. Kellogg estimated that in what became the contiguous United States, 71.7 percent of the nation’s forested lands in the year 1630 were in the East. That is, they extended from the Atlantic Ocean westward, petering out in the prairie, or Great Plains. By Kellogg’s estimate, the twelve states along the Atlantic coast out to and including the Appalachian Mountains were, on average, 93 percent forest covered in 1630.

Western forests, however, were relatively small in terms of the landscape they occupied,

lumbering didn’t begin in earnest on the Pacific coast until the beginning of the twentieth century. By then, Europeans had been wrestling the eastern “wilderness” into submission for at least 250 years.

The first task for any settler was tree removal-that is, unless he was lucky enough to find and pay a premium for a beaver-created meadow good for growing hay and pasturing or an Indian-cleared field for planting crops. Trees were an impediment. They stood in the way of survival. They blocked sunlight from reaching the ground to energize the growth of the edible plants settlers cultivated. In the short run, settlers could avoid starvation by packing basic foodstuffs into their home site and by hunting and gathering. But survival in the long run meant transforming patches of forest into hospitable terrain for the practice of European-style subsistence agriculture, with its domesticated animals, pastures, crop fields, and hay meadows.

The preferred method of tree removal in many places was girdling, a technique that involved stripping away a ring of bark from around the trunk. Without the bark, through which nutrients flowed, the tree died, leaving a leafless skeleton that slowly dried out and decayed over ten to twenty years. Standing trees were a scourge, but the wood in them was a cheap luxury. The wood could be turned into lumber to build cabins, fences, and barns, and it could be cut and burnt as fuel for heating and cooking. One of the forgotten appeals of the New World for immigrants from England was that every family, rich or poor, could enjoy a luxury denied all but the well-to-do back home: warmth. In the old country, where forests in 1600 covered less than 10 percent of the landscape, fuel for cooking and heating was costly. Cost was not an issue in the New World. Hearth fires could burn around the clock.

Eventually, settlers could sell the wood products their forests provided, or trade them for manufactured goods. The potash that resulted from burning had value as a material for making soap and fertilizer. Bark was used in tanning leather. Demand for these materials grew in Europe as well, and selling them for export helped propel subsistence farmers into a commercial economy that spanned the Atlantic. White pine (Pinus strobus) was the wood of choice for building materials for both ships and homes. Because they grew tall, straight, and strong and because they were relatively free of knots, white pines made excellent masts for sailing ships and were also cut into cross yards and bowsprits. For houses and barns, they were sawed into boards for siding and flooring and cut into timbers and framing studs. One of white pine’s virtues is that it floats better than other conifers and most hardwoods. That meant it could be cut down, skidded over snow or ice in winter to the nearest river, and then, come spring, floated downstream to a sawmill. Settlers used white pines to build their homes, barns, schools, churches, corncribs, chicken coops, pigsties, and just about every other structure they required. (White pine was eventually used to construct the boxes in which most goods were shipped before cardboard.

The deforestation of the New World began very slowly, and forested lands didn’t reach their historic low point in the Northeast until the 1880s, when nearly half of them had been lost to agriculture.

The Great Plains had one big drawback: virtually no trees. The Great Lakes had plenty, and as railroad lines expanded, Chicago would grow and prosper by funneling wood west. With 2,500 wooden crossties required for each mile of track, the railroads consumed whole forests themselves. 8 By 1850, the U.S. population had grown to 23.3 million, and wood supplied 90 percent of the nation’s energy needs. Most of this wood was cut locally and burned in homes for heat and cooking. Demand for lumber exceeded its production. A U.S. census in that year introduced new categories for classifying land. Land cleared of forest for farm or other uses was called “improved.” Forested land was “unimproved.” The 1850 Census estimated that 100 million acres of former forest had been “improved.” This meant that roughly one-fourth of the original eastern forest had been cleared for other uses. That was just the beginning. The timber barons were rapacious.

According to Douglas W. MacCleery, a longtime policy analyst for the U.S. Forest Service and one of the reigning experts on the history of American forests. He wrote Wood was virtually the only fuel used in this country for most of its history. It warmed its citizens, produced its iron, drove its locomotives, steamboats, and stationary engines. Lumber, timbers and other structural products were the primary material used in houses, barns, fences, bridges, even dams and locks. Such products were essential to the development of rural economies across the nation, as well as to industry, transportation, and the building of cities. American forests-the products derived from them and the land they occupied-were, in a very real sense, the economic foundation of the nation.

In 1929, two U.S. Department of Agriculture economists, William Sparhawk and Warren Brush, surveyed Michigan and estimated that in less than one hundred years 92% of the state’s original forests had been cut down. They estimated that for every 2 trees that had been cut and harvested during the boom another tree had been lost to fire or otherwise wasted.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with the forests of the Northeast and Midwest commercially exhausted, the timber barons turned their saws and axes to the pine forests of Georgia and the Southeast and the giant conifers of the Pacific Northwest. Logging across the South exploded between 1880 and 1920. In 1919, the region produced 37% of the lumber consumed in the United States. And as in the Great Lakes, the timber barons left behind the making of devastating fires and soil erosion. By 1910, the Pacific Northwest was out-producing the Great Lakes region, and by 1920, it supplied 30% of the nation’s timber.

In his 1907 forest census, Royal Kellogg estimated that the nation had lost 43% of its forest, with anywhere from 40 to 70% stripped away in the Northeast and Midwest, depending on the state. The assault on southern forests was just beginning, and in the West it had barely begun. He ended his report on an ominous note: “We are cutting our forests three times faster than they are growing.

White pine harvests were dwindling, and hardwoods, including oak and yellow poplar, were in serious decline. Although the environmental damage was great, the words environment and ecology were not familiar at the time and weren’t in any case a big concern. Far more important was the scary idea that the country might run out of trees. “It was an alarming prospect that struck at the very heart of America’s self- image as the storehouse of boundless resources,” Michael Williams wrote. “The nation might be reduced to the state of some impoverished and denuded Mediterranean country.

Tambora’s explosive power dwarfed subsequent and more familiar volcanic eruptions. Because news in those days traveled by ship, word of the volcano’s devastation spread slowly in comparison to the better-known and better-documented eruption of Krakatoa sixty-eight years later (after the invention of the telegraph in 1837). But Tambora was much bigger (24 cubic miles of ejected debris) than Krakatoa (3.5 to 11 cubic miles), or the famed eruptions of Vesuvius (1.4 cubic miles) and Mount Saint Helens in Washington (less than 1 cubic mile).

Tambora blew ash and an estimated 400 million tons of sulfurous gases which reacted with water vapor and ozone to create an aerosol layer of sulfuric acid that reflected the sun’s warming rays back into space. This layer stayed up for months and years until the stratosphere’s gentle circulation gradually brought it back down into the troposphere, where the weather grabbed it and deposited it on earth in the form of mineral ash and nature’s acid rain. In the meantime-the summer after the eruption-crop failures dotted the Northern Hemisphere. Rice failed in parts of China, wheat and corn in Europe, potatoes in Ireland (where it rained nonstop for eight weeks and triggered a typhus epidemic that killed sixty-five thousand and spread to England and Europe). Famine spread across Europe and Asia. Food riots and insurrections swept France, which had already been caught up in chaos following Napoleon’s 1815 defeat at Waterloo.

Even if the land wasn’t as naturally fertile as settlers found in the Midwest, there was plenty of livestock in New England, and that meant lots of available manure for fertilizer to grow other things. Farmers in the East had the advantage of being close to burgeoning cities that were markets for virtually everything they raised. They would prosper by providing farm products too bulky or perishable to ship from the Midwest. They could import cheap Midwest grain and feed it to chickens, hogs, sheep, and cattle to produce eggs and meat. Some became dairymen, supplying milk, butter, and cheese. They expanded orchards and truck gardens to supply a growing populace with fruits and vegetables. They grew hay to supply the horses, mules, and other draft animals that supplied power for agriculture and manufacturing and pulled the trolleys and wagons in the cities. For those who quit, jobs could be had in southern New England towns that were filling up with mills and factories and were accessible by rail. Others made their way to New Bedford and other coastal ports to sign on as crewmen on whaling ships headed for the South Seas.

By 1840, reforestation was clearly evident in parts of New England. In western Massachusetts, perhaps half the farmland was abandoned within twenty years after 1850, and much of it was colonized by native white pines. By around 1880, the return of trees was evident in New York, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey. When loggers began to realize they were running out of forests to cut, they slowly learned to be tree farmers. Michael Williams estimated that trees were replanted on one million acres annually during the 1930s.

While the total amount of lumber and fuel wood consumed continued to rise with population growth until the peak year of 1906, per capita lumber consumption had by then already begun to drop. Growing use of coal, oil, natural gas, and electricity reduced demand for wood as fuel. Also, aluminum, steel, and, later, plastics began to be substituted for wood in building construction. In the 1920s, oil production began to revolutionize the ways Americans lived and fed themselves.

According to Douglas W. MacCleery, a U.S. Forest Service analyst, 27% of the nation’s cropland in 1910 was devoted to growing food for draft animals-the horses, mules, and oxen that provided transportation and did the heavy work on farms and in towns and cities. Crude oil, pumped out of the ground and refined into gasoline to fuel cars, trucks, and tractors, made draft animals obsolete. That freed some 70 million acres of land that had grown hay, oats, and corn for draft animals to instead grow food for people. Then, after 1935, another product of the petroleum era, chemical fertilizer, gradually came into widespread use to nourish new hybrid seeds and greatly increase yields. The result was that it took less land and labor to grow more food. In 1990, farmers grew five times more food per acre than farmers in 1930 had grown, and they farmed fewer acres. All the while, trees were recolonizing land. In the eastern third of the country between 1910 and 1959, an estimated 43.8 million acres of farmland reverted to forest, mainly in the Northeast. In the next two decades the process accelerated, with farmland returning to forest at a rate of 1,180,000 acres per year.

The forests are actually aggressively re-growing in a region that was stripped of all its trees a century ago. Those were the days of the iron industry, when trees were what kept the fires burning in the blast furnaces in Lakeville, Lime Rock, Sharon and on Mt. Riga.” From around 1730 to end of the Civil War, local trees were cut to make charcoal that was burned in furnaces to produce a malleable wrought iron in the form of bars or rods that local forgers or farmers could heat and fashion into horseshoes, pickaxes, sledgehammers, axes, sickles, and knives. They also made munitions.

In New England woodlots supplied fuel to households, each of which consumed 10 to 30 cords of wood per winter to heat a drafty house with an inefficient fireplace or stove.

The Fitchburg Railroad line ran along the south side of Walden Pond, and its locomotives burned wood for fuel. Some of that wood was cut nearby, and in the decade that followed Thoreau’s arrival, trees were stripped from the land to power the trains. By 1854, when Walden Pond, or Life in the Woods came out, forests in the area had been cut down to almost their low point. In other words, the region was more deforested than at any time before or since.

In 1910, more than 350,000 miles of rail lines had been built-up from only 10,000 miles in 1850. Crossties wore out (they weren’t treated with creosote until 1900). They had to be replaced on 50,000 miles of track annually, which meant cutting down 5 to 20 million acres of trees a year.

The 2000 Census had revealed a demographic tipping point: For the first time an absolute majority of the American people lived not in cities, not on farms, but in an ever- expanding suburban and exurban sprawl in between. 13 Never in history have so many people lived this way. In historical terms, sprawl blossomed overnight. Until 1950, suburbs had so few people that the Census Bureau hadn’t even created a category for them. But that changed quickly when a severe housing shortage after the Second World War led Washington to stimulate a home-building boom where land was available on the urban fringe. Suburbanites sprouted like crabgrass. By 1960, the census found Americans to be 34 percent urban, 33 percent rural, and 33% suburban,

Ancient cities had suburbs of a sort. They were slums on the fringes, outside the walls built around cities at enormous expense to fend off attackers. People lived outside the walls because they were unwelcome inside them. Downtowns were for genteel people-professionals and merchant classes-who lived in townhouses. People on the edges or outside the walls were of the working and underclasses, sometimes craftsmen, such as carpenters and tailors, and sometimes undesirables-outcasts, slaves, prostitutes, and lowly laborers in slaughterhouses, leather tanneries, soap making and other industries not wanted in town. “Even the word suburb suggested inferior manners, narrowness of view, and physical squalor,” wrote Professor Jackson. That all changed with the industrial revolution, when the squalor moved downtown. At first a few wealthy urbanites sought relief from it by building estates or mansions (which they sometimes called “cottages”) in the country, where they spent summers or weekends. Then came planned suburban communities to help people who could afford them escape cities. In 1868, Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvin Vaux began the creation of Riverside on the western edge of Chicago. It was the first of 16 suburbs around the country that they would design for the relatively wealthy. Their idea was to combine greenery, clean air, and rural tranquility with such urban comforts as piped-in water, sewer lines, paved roads, and gaslights. Riverside was a success, but it was Chicago’s great fire of 1871 that triggered an explosion of suburban growth and an expansion of commuter railroads. Affluent residents of secluded new homes could commute to work by rail and live far removed from the stink of stockyards and slaughterhouses and the pollution, crowds, and noise of the downtown factory and warehouse areas.

Remarkably, however, trees have grown back on roughly two-thirds of the land that forest researchers believe was forest covered in 1630. How many people live in it? Nearly 204 million, or two-thirds of the population of 308.7 million in 2010. That number includes everyone, rural and urban. If you subtract the 23 million people who live in the twenty largest eastern cities, you are left with about 179 million, or 58.2% of the total U.S. population-still a clear majority. Most of those people live among a lot of trees but not in what would traditionally be called a forest. Sprawl, for example, can include suburbs, exurbs, golf courses, cropland, pasture, parks, highway median strips, parking lots, McMansions, Burger Kings, and people. It obviously isn’t officially defined forest. Yet areas of sprawl, particularly in the East, are so covered with trees that they have the feel of a forest, and, as we shall see, for many wild creatures they have all the comforts of forest-and more.

24 percent of New York City’s land area is covered by the canopies of 5.2 million trees. Nationally, tree canopy covers about 27 percent of the urban landscape, on average. Not surprisingly, it is heaviest in the East.

In the most heavily populated region of the United States, the urban corridor that runs from Norfolk, Virginia, to Portland, Maine, with eight of the ten most densely populated states, forest cover varied from a low of 30.6 percent in Delaware to a high of 63.2% in Massachusetts. The corridor runs straight through Connecticut, the fourth most densely populated state, and one that is more than 60% forested. Three out of four residents live in or near land under enough trees to be called forestland if they weren’t there.

A vast agricultural landscape, largely devoid of trees except for small woodlots. This was a working landscape that held at its peak some 31 million people living on 6.1 million farms. Both wild flora and fauna were very much controlled. Pheasants, for example, were encouraged. Weasels weren’t. This control was sometimes benign, such as putting up a scarecrow to deter crop damage, and sometimes lethal, such as injecting a chicken’s egg with strychnine to kill the proverbial fox in the henhouse. Guns and traps were kept handy as well.

This farm acreage amounted to a huge doughnut of managed land around big cities, towns, and villages. It separated most people from the forest, or what was left of it, and its wild inhabitants. The doughnut, however, began to shrink from the 1940s on. Early postwar suburbs weren’t very friendly to wildlife. But that didn’t matter because, except for the odd squirrel and a few birds, there were precious few wild creatures around.

Turkeys, bears, beavers, geese, and other wildlife were just beginning to recover. They were in distant redoubts and refuges. Eventually, however, the conservation movement produced miraculous comebacks of many wild species across a landscape of regrown forests filling up with sprawl dwellers. And that is when relations between man and beast began to go awry. Growing populations of wild animals and birds became habituated to life with or near people. Sprawl became their home. To be sure, many species showed little or no appetite for sprawl, which fragments habitat, disrupts migration and travel patterns, reduces species diversity, and adversely impacts native habitats in other ways. For many species, however, sprawl had all the things that they needed to thrive, foremost among them being food, protection, and hiding places. Even species known to be people-shy-wild turkeys and bears, for example-accommodated as their numbers grew. In fact, the living arrangements of many Americans today amount to a vast wildlife management regime, although most people in my experience don’t think of it that way. Sprawl dwellers planted grass, trees, shrubs and bushes, and flower and vegetable gardens. They created backyard habitats with ponds and native plants, and put out food so they and their children could observe, firsthand, any wild creatures that might turn up.

The state’s beaver population was burgeoning, and so were complaints about beaver damage. They were gnawing down prized ornamental trees in expensively landscaped yards. They were building dams that were backing up water and creating swamps and ponds and flooded roads, driveways, basements, backyards, wells, septic systems, sewers, railroad culverts, utility line towers, and all sorts of other structures that had been built in low-lying areas in an era when people gave no thought to an animal they had never seen. Why should they? There was no reason to think about a creature that hadn’t existed in the state for two and a half centuries. Beavers had been wiped out of Massachusetts by 1750,

by 2002, real beavers were very much back-an estimated 70,000 of them, and counting.

According to the Wildlife Services Division of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, “Many experts believe that the cost of beaver damage is greater than that caused by any other wildlife species in the United States.” People and beavers were sharing the same habitat as never before. They had similar tastes in waterfront real estate. Both liked to live along brooks, streams, rivers, ponds, and lakes with lots of nice trees nearby. They did, however, have different tastes in landscaping. People liked to plant trees. Beavers liked to chew them down to build dams.

Beavers had flooded a family’s backyard and were stealing firewood logs from the stack beside their house to expand their dam in the woods out back.

LaFountain said people either loved him for solving their problems or loathed him for trapping and removing cute, furry animals. On occasion, people would confront him as he was carrying a live beaver in a trap back to his truck. He was too imposing a figure to threaten, but they sometimes said, “You’re not going to kill it, are you? It was a question he tried to deflect by saying that the beavers were being captured alive in cage traps, treated humanely, and that his methods not only were legal but had won the praises of animal protection groups. His customers, on the other hand, usually didn’t ask. Asking would result in an answer they didn’t want to hear. They wanted to assume that the animals causing their problems would be removed by LaFountain and then relocated to some place where they could live happily ever after.

Beavers create a pond that serves to protect them from predators. In doing this, they create and maintain their own habitat by impounding water behind the dams, which look like loose piles of sticks but are surprisingly strong and largely watertight. They usually start by pushing sediment, rocks, and sticks into a ridge perpendicular to the stream flow. They anchor tree branches to the ridge and to the bank of the stream, push other sticks through the ridge parallel to the stream and, on this foundation, layer leafy branches and more sticks, twigs, and aquatic plants to form a tight mesh. To stop leaks, they push in mud, sand, corncobs, stones, and whatever else they can find.

Beaver dams create swamps, or wetlands, which are beneficial to countless other species of fauna and flora. These wetlands are lodes of species diversity, the “rain forests of the North.” By chewing down trees and maintaining their dams to keep the water level behind them fairly constant, beavers slow moving water, allowing sediments in it to fall out to create rich layers of soil and, eventually, broad lowland meadows that serve as breaks from the surrounding forest. Beaver dams filter pollutants, help control seasonal flooding, and reduce erosion. Because the beaver is one of the few animals (man is another) capable of engineering the landscape for their own purposes, biologists call it a “keystone species.

Paleo-Americans and Indians made use of fur-bearing mammals going back at least eleven thousand years, and archaeologists found that beavers were important sources of food, clothing, and tools for tribes in the Northeast. Their teeth became cutting and gouging tools, and beaver bones had many uses,

Algonquians and other tribes often divided hunting territory into units controlled by families and marked individual beaver lodges to signal that their occupants belonged to a particular family. Catching and killing beavers was more difficult. Indians used a variety of weapons and tools, including bows and arrows, axes, spears, clubs, nets, snares, deadfall traps, and leg and body traps. Sometimes they breached the dams and drained the ponds so the lodge access hole was exposed.

In 1626, the Merchant Adventurers, figuring they’d never get paid back, let alone make a profit, cut their losses and sold their shares to eight Pilgrim leaders for £1,800. The fur trade picked up in the 1630s, when the Mayflower Pilgrims shipped more than two thousand beaver skins to England. Wrote Nick Bunker in Making Haste from Babylon:

The Mayflower Pilgrims and Their World: “Without the fur trade, the colony would have failed, and the name of the ship would have faded into oblivion.

A much different story unfolded in what became New York City. It is ironic that the city today is a focus of protests against sellers and wearers of fur because New York City owes its very existence and location to fur in general and to the beaver in particular. Indeed, the rodent was deemed so important that the city’s official seal, created in 1686, depicts five living creatures: an eagle, a European sailor, an Algonquian Indian, and two beavers.

Americans who think trapping is inhumane and wearing fur is repugnant might be astonished to learn how important a role beavers played in North American history: The exploration and conquest of the northern United States and Canada were propelled in large part by the economic rewards of finding, catching, killing, eviscerating, and skinning these fifty-pound aquatic rodents. The reason was that Dutch, French, and English explorers to the New World, unlike the Spanish, found no gold and treasure. But they did find a paycheck. The beaver became America’s first commodity animal. Beaver pelts became a currency. Trade in them created an economic network that spanned the Atlantic Ocean from the New World wilderness to the royal courts of Europe and lasted for 300 years. The network’s tentacles connected Indian hunters and trappers to frontier trading posts, middlemen, transporters, exporters, processors, and sellers.

As beavers dwindled and competition for them grew, Indian traders had to push deeper into territory controlled by other Indian traders, and European traders began to court their competitors’ suppliers. These tactics fractured alliances, set off rivalries, and touched off tribal wars.

With beavers largely extirpated east of the Appalachians, English traders and their Indian partners moved west into the Ohio Valley and the Great Lakes region, alarming the French and their Indian partners in Canada. The French responded by building forts on Lake Champlain, the Niagara River, and other places and sending troops into the Ohio Valley. The French moves, in turn, alarmed Indian trading partners of the English-the six nations of the Iroquois League (Mohawk, Seneca, Cayuga, Oneida, Onondaga, Tuscarora).

In the early 1830s, three things came along just in time to keep the beaver from being completely wiped out: nutria, silk, and cholera. The nutria, or coypu, is an aquatic rat (Myocastor coypus) found in South America. Smaller than a beaver but larger than a muskrat, it has webbed feet and a long round tail. The fur of nutria mimics the beaver’s in many ways, and it was, at the time, plentiful and much cheaper than beaver.

At the same time, inexpensive silk from China was making its way to European hatmakers, and silk hats, with their different color and feel, became highly fashionable

From roughly 1500 to 1900-a period nearly double the time the United States of America has existed as a nation-tens of millions of beavers were killed across the continent. By some estimates, only one hundred thousand or so beavers were left on the entire continent, most of them in the Canadian outback.

The motivations conservationists had for restoring healthy populations of beavers was so they could build dams and re-create the rich wetland ecosystems that had long been regarded as useless swamps to be drained and destroyed. Between 1901 and 1907, state wildlife agents released thirty-four Canadian beavers into the Adirondacks and outlawed trapping them. By the end of 1907, the population had grown to an estimated one hundred animals. Eight years later, in 1915, the Adirondacks had an estimated 15,000 beavers.

laying out railroad tracks, roads, highways, water pipes, and drainage systems in valleys, beside rivers, and in relatively flat lowlands. Along these same routes went utility poles, electricity lines, and telephone wires. Planners laid out these arteries with periodic flooding in mind, but not flooding caused by beavers. Yet much of the vast grid that keeps America moving and humming was built on prime beaver habitat. So were a lot of homes. As people sprawled out, beavers sprawled in,

The biological carrying capacity means the point at which the beaver population (or any other species) reaches the limit of food and other resources that its habitat can sustain. Its adjunct, ecological carrying capacity, is the point beyond which a species adversely affects its habitat and the flora and other fauna within it. Social carrying capacity is more subjective. The phrase was coined to designate the point at which problems or damage caused by a wild population outweigh its benefits in the public mind.

Residents all over the state were grousing about beavers flooding driveways, chewing down valuable trees, inundating septic tanks and basements, contaminating wells, and threatening town water supplies. Beavers were damming up culverts and causing water in swamps to rise to levels threatening the integrity of the foundations of towers holding electricity and communication lines. Their dams were flooding low-lying commercial forests, damaging timber crops. Backed-up water in beaver ponds soaked into railroad beds, saturating them, causing them to soften, and increasing the threat of train derailments. Beaver dams disrupted the water flows around electronic power generation facilities and saturated toxic waste sites, causing leaching.

It was around this time when Don LaFountain stopped calling himself a “recreational trapper” and started calling himself a “professional wildlife damage controller.” The difference? As a weekend hobbyist, he could sell the pelt of each dead beaver he trapped for $20, more or less depending on the vagaries of the fur auction market. As a licensed professional, he could charge $150 for removing a “problem beaver,” $750 for removing a typical family of five, and $1,000 and more for installing “beaver deceivers.” 15 By 2012, LaFountain had enough business to restrict clientele to large landowners, railroads, watersheds, and utilities, doing consulting and beaver problem-solving for $75 an hour and up.

Voters assumed that trapping beavers alive would spare their lives because the animals could be relocated: that is, transported to a new life in a new habitat, free of the pressures and complaints of modern, suburban man, to live out their lives. It’s a nice thought. The problem with it is that relocating wild animals in Massachusetts is illegal, as it is in many other states, for several reasons. While relocation sounds good, live-trapping and moving animals puts them under a lot of stress, and their survival rate is relatively low. The creatures arrive in a strange new environment and find themselves competing with animals already there. They may bring diseases with them. The unstated bottom line is this: Under the laws of Massachusetts and many other states, it doesn’t matter whether wild animals are captured in traps judged to be humane or not, they end up just as dead. After they die, they are skinned and fleshed, and their pelts are dried.

More expensive “beaver deceiver” or “beaver baffler” systems of pipes and screens would keep the pond below flood stage and allow the beavers to stay. But this way wasn’t perfect either. Beavers are clever. Sometimes they find the water intake pipe and plug it, allowing water to rise.

Deer hunters pump more than $12 billion into the economy annually. They spend more on gear than do fishermen and golfers combined. Besides weaponry, they outfit themselves with night vision devices for scouting, heat-seeking scopes and trail cameras to locate deer, global-positioning satellite modules to know where they are, and all- terrain vehicles to get places fast. They dress up in camouflage clothing treated to hide the human scent. They buy mineral attractants and bottles said to contain potent estrus urine taken from female deer in heat to lure amorous bucks. If, however, the goal is to reduce a burgeoning population of white-tailed deer, then deer season is a colossal failure. Hunters kill more than 6 million whitetails each fall, but that’s not nearly enough to do the job. Deer population densities are so high in some places that it would take kill ratios several times higher just to stabilize local herds.

A century ago, whitetails had been wiped out of many areas by uncontrolled hunting. They reached a historic low around 1890 of an estimated 350,000 animals in isolated pockets of the country. Ernest Thompson Seton in 1909 put the figure for 1900 at 500,000 in all of North America.

By 2006, deer had collectively become a mass transit system for ticks carrying Lyme disease. Deer damage to farm crops and forests topped $850 million, and whitetails were eating their way through more than $250 million worth of landscaping, gardens, and shrubbery. Deer, by their browsing habits, had degraded forest ecosystems all over the East. They were preventing forests from regenerating by eating the plants, woody shrubs, and small trees that grew under the canopies of large trees from ground level to as high up as their mouths could reach when they stood on their hind legs. This essentially removed the habitat of creatures that lived in that forest understory, putting some populations of songbirds, for example, at risk. But threats to forests and songbirds paled in comparison to the whitetail’s menace to people in the form of collisions of deer and motor vehicles, which were occurring at a rate of 3,000 to 4,000 per day.

Krech estimated that annual exports of up to 85,000 deerskins in the late 1600s grew to over 500,000 skins in the middle 1700s before declining. “The deerskin trade was as good as over after 1800”. After three centuries of slaughter “inveigled by the white tradesman and underwritten by the European buying public,” Indians and traders “left the land [in the East] nearly barren of certain wildlife and the Indians themselves destitute of subsistence and cultural options.” But that did not mean an end to deer killing.

Commercial hunters quickly took their toll. A swell of immigrants created vast new markets for professionally shot venison. Market hunters killed deer by the tens of thousands, supplying venison to Great Lakes logging camps and sending hides to Philadelphia, where domestic tanning and leather goods industries were growing. Factories there turned out leather stockings, hats, caps, gloves, breeches, aprons, waistcoats, doublets, entire suits, coats, belts, shoe uppers, and boot linings. Deerskin could be used to make opaque window coverings, wall covers, snow shoe netting, upholstery fabric, bellows, harnessing, saddles, handbags, book bindings, and bull whips. Antlers were used to make such items as hat racks, knife handles, and buttons. Deer hair was used to stuff saddles and furniture. Deer tallow was used to make candles. The third stage, the so-called era of extermination in the last half of the nineteenth century, was the worst, and not just for deer. All wildlife suffered, from bison to songbirds. Demand for wild products soared as immigrants poured in and the U.S. population grew to 76 million. Any wild species with any value was killed for meat, fur, or feathers. Money flowed.

Across most of the United States by the end of the nineteenth century white-tailed deer were so scarce that market hunters no longer bothered with them. Deer had been wiped out of New England except for northern Maine and Cape Cod (where a herd of two hundred had survived since colonial days). A few thousand roamed the isolated parts of the Adirondack and Catskill mountains in New York. Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, and Ohio had virtually none. In the swampy redoubts of the Carolinas and Georgia, along the Gulf Coast and down the Mississippi Valley, remnants held out. By 1900, white-tailed deer had been reduced to 1 percent of their estimated pre-Columbian numbers.

What to do? There were two ways to stop deer from starving: grow more food for them in place or truck food in. State wildlife managers had long opposed supplemental feeding. They knew hunting clubs and private groups were illicitly feeding corn and hay, but they were loath to allow supplemental deer feeding on public lands. In 1961, however, a severely cold winter changed their minds and they consented to feeding deer surplus government corn “for emergency purposes.” That decision, popular with hunters, opened the door to emergency supplemental feeding in the winters of 1964, 1968, and 1970. The first option-growing more deer food-made more sense to deer biologists, who in the early 1970s persuaded state game managers to launch a $20 million “deer habitat management” program. It was, essentially, a “kill trees to save deer” scheme in which workers tore into the forest with bulldozers, chain saws, and axes to create “ideal mixtures of tree species, age classes of trees, forest openings, and winter cover. Edges, in a word. When the timber prices went up, the state invited commercial loggers to do the work for them. Between 1972 and 1987, loggers and state agents created more than seventy thousand acres of “forest openings”-holes in the woods created to help a creature that had historically lived someplace else. The holes allowed growth of the same young, ground-level vegetation that had fed the whitetail proliferation in the North in the first place and, as a result, created a deer-hunting industry on which northerners now depended. Growing more local whitetail food, however, didn’t stop hunters from trucking in supplemental food. Indeed, putting out food piles became a standard hunting strategy, even though many hunters likened the practice to “putting garbage in the woods” and labeled it unethical and unsportsmanlike. It doesn’t take a trained wildlife manager or veterinarian to understand what happens when you aggregate wild animals by drawing them together with food. Any kindergarten teacher will tell you that if you put thirty five-year-olds in a room and one of them has a cold, pretty soon they’ll all have colds-and they will bring those colds home to their families. The same thing happens at feeding stations on deer farms and bait piles set out for wild whitetails. One diseased deer leaves a little mucus behind, another deer picks it up.

One of the first battles between people who wanted to control excess deer and people who wanted to protect deer from harm played out in western Massachusetts in the late 1980s when those responsible for maintaining a safe, clean water supply for some 2.5 million people in and around Boston realized that they could no longer ignore the fact that the proliferation of white-tailed deer in the woods around the Quabbin Reservoir was putting that water supply at risk.

A typical forest in the region would have trees of all ages and many species, bushes, tangles of bramble, and other underbrush. The Quabbin deer had eaten away oak and other hardwood seedlings and had cleaned out much of the underbrush and ground vegetation. The landscape under the canopy of old trees looked like a park, and visitors could see through it for hundreds of yards. The trouble was that understory vegetation was vital to the watershed’s ability to hold and filter the rainwater that replenished the reservoir. The deer were creating a forest with trees the same age, sparse ground cover, and increasing erosion-all threatening to the drinking water supply. “It looked like the Serengeti Plain, with herds of deer running around like antelopes,” David Kittredge, a forester at the University of Massachusetts, told me later.

The Metropolitan District Commission, the body in charge of managing the reservoir at the time, considered and rejected several nonlethal options, including birth control, the solution favored by most people against lethal control. It was a pipe dream then, and it still is. More than two decades later, injecting females with fertility-control drugs remains too expensive and ineffective for use on free-roaming deer. The commission also looked at chemical repellents, plastic tree tubes, fencing, and a catch-and-relocate strategy. All these options, favored by those against killing the deer, were flawed and too costly, the commissioners decided. The commission studied deer predators. Already present were bobcats and coyotes, but they alone couldn’t control the deer population. Quabbin was too small to contain the mountain lions and wolves that some people suggested be introduced. Would people nearby with children, pets, or livestock really tolerate wolf packs and cougars? Obviously not. The only viable option, the commission decided, was the least well liked: hunting. Hundreds of people turned up at workshops, open forums, and public hearings in 1989 and 1990. Some carried placards reading “Killing for fun is obscene” and “Stop the war on wildlife. The most radical antihunters were advocates of animal rights who argued that it was morally wrong to kill a deer for sport and that the lives of individual animals mattered. Others argued that since man’s mismanagement was the cause of the problem, the obvious solution was for man to get out and leave nature alone. In interviews with Professor Dizard, these people used phrases such as “Let nature heal herself,” “Nature knows best,” and “Nature provides.” Deer and forest would work things out if only man stopped meddling.

While the battle raged, the commission considered three options for killing deer: hiring of sharpshooters, a recreational hunt open to licensed hunters, and a controlled hunt with a limited number of hunters following strict rules. The first option, sharpshooters, was ruled out because Massachusetts had no government program to certify their competence. Besides, the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife opposed them because the public (hunters) would thereby be denied access to a public resource. A recreational hunt was likewise ruled out because the commission felt it couldn’t be adequately controlled and because it would draw the most protest. A controlled hunt was agreed to for the autumn of 1991. While protesters demonstrated and antihunting groups filed lawsuits, hunters killed 576 deer over nine days. Opponents called the hunt a “slaughter.” The leader of Citizens to End Animal Suffering and Exploitation (CEASE) said the hunters had “wiped out the deer population.”

The sharpshooters used relatively small-caliber .223 rifles with infrared telescopes and silencers to kill deer with single shots through the head. From elevated stands, they aimed down at the deer so that any errant bullets would go safely into the ground. The shooters worked at dawn, at dusk, and at night, virtually unseen by residents. With, say, a dozen deer feeding at a bait pile, shooters aimed at dominant deer (leaders) first, then adult does and the rest (often confused and hesitant) in rapid succession, aiming to kill them all in a matter of seconds. Afterward, they gathered up the carcasses, along with bloody leaves and other debris, leaving no evidence of the cull. Over a ten-day period in February 2001 they killed 324 deer at a cost of about $350 per deer.

All went well. Once the geese were corralled, some of the men waded into a maelstrom of thrashing honkers, grabbing them by their wings and legs and passing them to other men, who stuffed them into the poultry crates, five or six birds to a crate. In all, 125 geese were rounded up and crated.

The phone in the Kent town office began to ring around 9 A.M. Word of the roundup had gotten out. For authorizing $8,000 for goose removal, Annmarie Baisley was denounced as “an assassin” and worse. Baisley was a chain-smoking, no-nonsense administrator, but as the number of calls mounted, some coming from far away, and as they began to include threats, she shut down the office early. The first protesters, along with crews from local TV stations, arrived shortly thereafter, one with a placard reading “Baisley the butcher. A year later, Baisley was still getting hate mail such as this: “It’s time to reflect on your act of sorrow. It’s your one year anniversary on sentencing families of Canadian geese to death. Sleep well.”

Canada geese, with their distinctive black heads and necks and white “chin strap” feathers, number perhaps 8 to 10 million in North America and are a collection of at least eleven subspecies ranging from the smallest, the cackling Canada goose, which weighs about three pounds and travels fast and far, to the largest, or the giant Canada goose, which weighs ten to twenty pounds and migrates relatively short distances. They can live for twenty-four years, they mate for life, and typically begin breeding at age three. Adult pairs try to return to the same place each spring to nest. The female lays two to eight eggs, sitting on them for about twenty-five to twenty-eight days, until they hatch, while the male helps ward off predators, which range from Arctic foxes and gulls in the far North to raccoons and ravens in temperate zones.

The contrast couldn’t be sharper between these migrating flocks, estimated at 4 million, and the geese that occupy the local landscape and seem to go nowhere very fast. For some people, these stay-put geese, estimated at more than 4 million, are just as majestic as the ones that migrate.

Some people call them “lawn carp. The digestive tract of a goose evolved to its present small and lightweight form to make flying easier, but at the expense of digestive efficiency. Canada geese are herbivores almost exclusively. They feed mainly on grasses and sedges in summer and on seeds, grains, berries, and other higher-energy foods in fall and winter. Usually, less than 40 percent of this food is digested while passing through their systems in thirty minutes to an hour. This process creates a lot of feces, which geese void from their bowels in the form of wet droppings roughly five times an hour.

Entrepreneurs, eyeing a dispute from which they might profit, jumped into the fray on both sides. To the anti-killing factions they suggested ways to save the geese and avoid their messes. They offered to sell all sorts of contraptions and noisemakers to scare the geese away. They proffered trained border collies and handlers to chase the geese somewhere else. Experts were available to find nests and addle or oil eggs to stop them from hatching and thereby limit population growth without killing adult geese. Chemical repellents and goose birth control pills were touted. Landscapers offered to create terrain geese didn’t like.

Contractors could be hired to round up geese and remove them for processing into food for the needy. Federal agents offered up their removal services. National animal rights and animal protection groups against lethal removals offered advice and solicited donations. A few entrepreneurs even built machines like hockey-ice Zambonis to vacuum goose feces off grass.

The battle of Clarkstown lasted 3 years. Then, in 1996 and 1997, town officials paid $6,500 to remove 452 geese. That amounted to only $14.38 per bird-a bargain in comparison to what happened next. The goose partisans upped political pressure on town officials and got enough votes to stop the lethal roundups and instead hire Mary Felegy, president of Fair Game Goose Management, and her border collies to hound the remaining three hundred or so geese off town parks and ponds. The geese flee because the collies mimic their historic predators, foxes and wolves. Felegy was paid $36,000 a year. That’s $120 per bird-eight times more than lethal removal and, in the opinion of the town supervisor, Charlie Holbrook, a waste of taxpayer money. At $14.38 per dead bird, the yield is goose breast meat at a relative bargain price of about $5 a pound. Harassed geese at a cost of $120 per bird yields nothing but more excrement somewhere else. “The collie people have a great thing going,” Gregory Chasko, a Connecticut wildlife official, told me at the time. “They chase the geese off the park in the morning and they fly to the golf course. Then they chase them off the golf course in the afternoon and they fly back to the park.

The correct answer is that today’s geese did not stop migrating. They never migrated. Neither did their parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents. You’d have to go back at least a century to find ancestors of these geese that migrated. And you would have to go back much further to discover why they stopped. The skies over Jamestown and Plymouth colonies were so filled with migrating birds in the spring and fall that they sometimes darkened the sky like a solar eclipse. Along the Atlantic coast, millions of ducks and geese moved through Cape Cod and Long Island Sound into the Chesapeake Bay and farther south. In the Midwest, millions more birds funneled down the Mississippi watershed to Arkansas and beyond.

By the early nineteenth century, waterfowl market gunners were embarked on an arms race to deliver more killing power to their targets. They opted for bigger guns-guns so big that a man couldn’t lift them. They had to be mounted on boats. The biggest of these, called punt guns, had barrels up to two inches in diameter. They held a pound of shot pellets and had to be strapped down so the boat could absorb the enormous recoil.

The resultant shot cut a swath of death up to eight feet wide and a hundred yards long. A hundred or more geese or ducks with a single shot was not unusual. To help lure birds in and keep them around, the gunners would spread shelled corn across fields and shallow feeding marshes and hide in raft-like shooting platforms called sinkboxes that made them difficult to notice from the air and impossible to see from the water. Perhaps the best tools at their disposal, however, were live decoys. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, waterfowlers-including men wealthy enough to belong to shooting clubs-brought out, in addition to wooden decoys, dozens of live geese or ducks, some tethered and others trained, to bob in the marsh or strut in the cornfield and make noise, adding all-important authenticity to the ruse.

Even songbirds were dispatched for meat and feathers.

In January 1934, Roosevelt appointed a three-man committee to recommend ways to pay for waterfowl restoration. On it was Aldo Leopold, of the U.S. Forest Service; Thomas Beck, editor of Collier’s magazine; and Jay Norwood Darling, a political cartoonist for the Des Moines Register and a Republican.

Roosevelt signed the Migratory Bird Hunting Stamp Act, under which waterfowl hunters paid one dollar for a federal stamp, the proceeds for use to acquire land for what became the 5.2-million-acre National Wildlife Refuge System. One goal was to create refuges along the continent’s four major migratory flyways at intervals of about one hundred miles.

Darling turned out to be an energetic administrator. When he took over, the bureau had only twenty-four game wardens for the whole country. He hired more and dispatched them in strike forces to poaching hot spots, eventually using airplanes to spot lawbreakers. In 1935, he imposed the tightest hunting restrictions yet seen, banning the use of corn and other grains as bait, shutting the hunting season down to thirty days, cutting bag limits to ten ducks and four geese, outlawing shotguns that could hold more than three shots at a time, banning sinkboxes and offshore blinds, and fending off critics in Congress, whose constituents howled at the restrictions.

The most significant move that Darling made, by far, was to outlaw the use of live decoys. Darling’s new rules would make waterfowling more sporting: “The new regulations practically wipe out all the artificial aids which the fowler has used for so many seasons and restores more wholesome principles to the sport of shooting. The man who is successful this season will need to know more than how to handle a shotgun; he will need to know wind, weather and the habits of the birds. He will be a duck hunter rather than a duck shooter.”

No one could foresee it at the time, but outlawing live decoy flocks was the first step in creating large populations of nuisance Canada geese. The regulations suddenly made ducks and geese in these flocks legally unusable for hunting. Enforcement was ramped up, and because decoy flocks were visible and obvious, continuing to use them made hunters vulnerable to arrest, and that gave them pause. Most replaced their live birds with wooden facsimiles. The result was that tens of thousands of live decoys became superfluous, including an estimated fifteen thousand geese along the Atlantic coast alone. The market for them collapsed. Some hunting groups gave their birds away. Others sold them for pennies on the dollar. Suddenly live decoy birds were either free or a bargain, and people began to buy them up for other uses. Farmers took them to raise as barnyard fowl for meat, eggs, and feathers. Towns and wealthy landowners bought some to adorn their ponds or to join the odd peacock on the village square. More important, state fish and wildlife departments snapped them up as breeding flocks to stock local marshes and newly created waterfowl refuges in hopes of growing healthy populations to supplement imperiled migratory flocks. These restocking efforts went on for decades-well into the 1990s in some states. Migrating birds have a little-understood internal compass-an instinctual homing ability tied, perhaps, to magnetic direction-to fly back to the place where they first learned to fly or where they nested as adults in previous years. Captive geese hadn’t migrated in many generations, but wildlife managers hoped that once they were put out into local marshes and refuges they would eventually take up migration. That didn’t happen. The problem was that the birds had been born and learned to fly locally and had nested locally. They were already “home,” so to speak. They were at or nearby their birthplace and nesting location. Goslings learn habits from parents and other geese around them, and those birds had been conditioned to hang around and rely on their human handlers for food. “After release, there was little biological incentive for the flocks to change their behavior,

The big natural advantage the giants had was a large body mass that allowed them to endure colder temperatures than smaller geese, and that meant they didn’t have to migrate very far south in winter to warmer climes. Their size also meant that flying took more effort than it did for smaller birds. For this and perhaps other reasons, the giants didn’t migrate to the tundra to nest and molt in the spring like smaller geese.

Some goose restoration programs had been using giants for years without knowing it.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service would later estimate that at the time of the Hanson discovery some sixty-three thousand maximas lived in the midwestern and plains states. The giants were hidden in plain sight. State agencies rushed to propagate the big birds. Geese of all kinds were still so scarce that hunting them was prohibited across wide regions. Perhaps the giants could fill the void. In his 1965 book The Giant Canada Goose, Hanson noted that towns in Minnesota were starting flocks of giants on their lakes and was encouraged enough to pronounce the future of the giants “indeed bright”-a phrase a U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service waterfowl expert would later call “a gross understatement.

The size of the giants made them relatively lethargic. They didn’t need to migrate very far. The captive breeding programs only reinforced those proclivities. They were raised on farms, fenced in, fed poultry mash, and wintered in buildings like chicken coops. Transferred to waterfowl refuges as goslings, they flourished. Wildlife agents congratulated themselves,

The zealotry of restoration efforts was understandable. The government agents had been restoring wetlands and creating waterfowl refuges in which geese could flourish to the delight of hunters, and now they were helping to save a species from extinction-or so they thought. Ironically, they were building healthy goose populations in newly created refuges where the birds had never permanently existed or nested before.

Developers turned millions of acres of farmland and woods into lawns, ponds, golf courses, corporate parks, school campuses, soccer fields, playgrounds, and parks, all planted in what happened to be the favorite food of Canada geese: grass. Better still, because it was mowed regularly, this grass always had plenty of fresh, tender growth that was much more palatable than tough grown-up grass. These grassy landscapes had long sight lines-which made geese feel comfortable because they could more easily spot any predators

Adult geese, because of their large size and aggressiveness, have few predators to begin with, although wolves, coyotes, bears, owls, and eagles have been known to take nesting adults. Few of these creatures existed in Twin Cities sprawl. Egg predators, including raccoons, foxes, crows, snakes, snapping turtles, and various raptors and gulls, were more numerous but not very effective. Parental geese are fierce nest defenders.

Most people weren’t aware of the aircraft-bird collision problem. Federal figures showed that such collisions had quadrupled from 1,759 in 1990 to 7,666 in 2007. Most caused minor damage because the birds involved were relatively small. Collisions with geese were far more serious. In 1995, for example, Canada geese were ingested in two of four engines on an Air France Concorde departing JFK International, causing more than $7 million in damage. That same year, four Canada geese were sucked into the engines of an Air Force jet in Alaska, causing it to crash and killing all twenty-four people aboard.

We were on a farm near Batesville. Its owner had invited Roy to “thin out” the wild turkeys on his land. He said they’d gotten so thick that they plucked seed corn out of the ground almost as fast as he could plant it. The turkeys were costing him money.

Turkey hunting in the spring is about sex and deceit. It is a game of sounds. Normally, males gobble and hens come running. Males are serial breeders. But each impregnated hen means that there’s one less to breed. As interested hens thin out, the gobbler’s sex drive propels him to look for more. Spring turkey hunters pretend they are hens, or competing toms, with their calls. Some hunters can imitate turkeys with their own vocal cords and mouths. Others use reeds, wooden boxes, and slates designed to mimic a range of more than two dozen yelps, clucks, cackles, and purrs turkeys use to communicate. The hunter’s call has to sound convincing enough to overcome the gobbler’s wariness.

Wild turkeys seemed to be everywhere, perhaps 10 million strong, when European settlers arrived. They were easy to find and kill for food and feathers, and their numbers were steadily reduced. By the early twentieth century they were facing extinction in isolated, remnant flocks. By 1920, conservationists estimated that as few as thirty thousand birds were left on the entire continent. Early restoration attempts failed. Not until the 1950s did government wildlife agents develop successful techniques for repopulating regions where turkeys had been extirpated.

Farmers were first to complain, accusing turkeys of eating their crops. Sprawl dwellers began to report that aggressive birds were menacing them, their pets, and their children. Environmentalists complained that in some places the turkeys were an invasive species damaging ecosystems meant for native animals and plants.