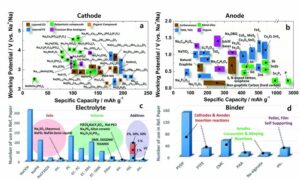

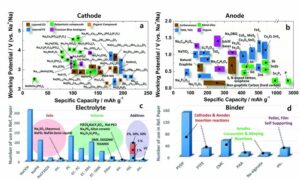

Recent research progress in sodium ion batteries: (a) cathode, (b) anode, (c) electrolyte and (d) binder. Source: Hwang J (2017) Sodium-ion batteries: present and future. Chem. Soc. Review 46: 3529-3614 DOI: 10.1039/C6CS00776G

Preface. If lithium were used for both EV and utility scale energy storage, reserves would not last long. But there’s a lot of sodium. A sodium battery is better than lithium as well because it is safer and keeps most of the charge when temperatures fall far below freezing.

But sodium batteries have an enormous disadvantage: they need to be bigger than lithium batteries to hold the same electrical charge. So this doesn’t solve the #1 energy crisis problem: Transportation. They’d be far too heavy to electrify long-haul trucks, tractors, locomotives, ships, and other heavy-duty vehicles that run on diesel.

Their best use would be large-scale electric grid energy storage. In fact, Sodium sulfur (NaS) batteries are the only kind of large-scale energy storage for which there are enough materials on earth (Barnhart 2013).

Although Barnhart may be wrong about the amounts of sulfur available. Sure, sulfur is the fifth most common element in the world, but deposits large enough to exploit are extremely rare, mostly near volcanoes. Most sulfur or sulfates are combined with copper, iron, lead, zinc, barium, calcium (aka gypsum), magnesium, and sodium.

Today 80% comes from oil and natural gas refining into pure elemental sulfur, safe and easy to transport, unlike sulfuric acid, and with the bonus of preventing sulfur dioxide emissions and acid rain. But there are scientists warning about 25 years of conventional oil left in the world at current rates of consumption. Others say more than that. But whatever the amount left, exponential growth from population and capitalism shortens consumption time.

Continue reading →

Preface. Hurricane Katrina cost somewhere between $109 and $250 billion dollars (Amadero 2017). Estimates of hurricane Harvey range from $100 to $190 billion (Kollewe 2017, Lanktree 2017).

Preface. Hurricane Katrina cost somewhere between $109 and $250 billion dollars (Amadero 2017). Estimates of hurricane Harvey range from $100 to $190 billion (Kollewe 2017, Lanktree 2017).

Source: Salt Lake Tribune.

Source: Salt Lake Tribune.